I have added this article specifically for the many aid workers who come to help in Haiti but are unaware of the highly patterned and logical strategies of survival that can be summarized under the rubric, “Socialization for Scarcity.” On the one hand, aid workers often mistakenly interpret rural Haitian individuals and households to be independent, isolated, with restricted mechanisms for sharing and hence in desperate need of a safety net. As will be seen below, the evidence does not bear this out. Moreover, aid workers also often misinterpret dependency on local, radically simplistic imported technologies as an illogical, maladaptive resistance to change and development. NGO workers and entrepreneurs who have attempted to introduce new, profitable or seemingly life-saving innovations have most often found their projects received with indifference on the part of the farmers. However, it is precisely this near zero-risk, zero-investment approach to productive livelihood strategies that have enabled people in Haiti to thrive despite two centuries of embargoes, internecine warfare, political upheaval and natural disaster.

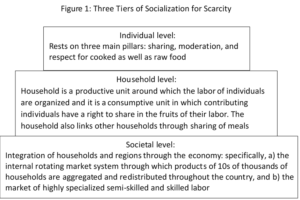

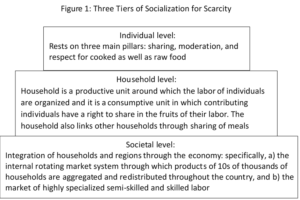

This article reaffirms Alvarez and Murray’s observation that food consumption patterns in rural Haiti are integrated and adapted to resource stress and availability in a manner the authors called, “socialization for scarcity.” This essential survival strategy for both individuals and the group “rests on three main pillars: sharing, moderation, and respect for cooked as well as raw food” (Alvarez and Murray 1981: i). Here I begin with Alvarez and Murray’s postulate, but I take the concept beyond the scholars’ original intention. Despite alluding to the ‘group,’ Alvarez and Murray limited their analysis largely to the individual. Here I extend the discussion to socialization for scarcity at the household level and at the societal level to present a three-tiered model as below:

Socialization for Scarcity: Individual level

‘Socialization for scarcity’ begins early in the rural Haitian child’s life. Children are censured for eating too much, called gwo voras (big consumer) and visye (greedy). Conversely, they are encouraged to share with others. As anyone familiar with rural Haiti knows, “It is not rare to see 15 children drink out of a bottle of kola, or to watch a dozen children eating from a piece of corn.” (Alvarez and Murray 1981: i). The sharing among children is mostly focused on snacks. The temptation for adults to eat another household’s meal is moderated by the fear of receiving poisoned or hexed meals from strangers, or someone on bad terms with the hungry individual’s family.

Even at early ages children devote considerable time to getting food. Alvarez and Murray (1981) found that children spent about 23% of each 24-hour period observing what was being cooked, attending to what others were eating, scrounging for food, looking for fuel or water for cooking, or fetching food items for their parents. We could add that children also learn early to independently raid gardens, and dig and cook sweet potatoes with their peers. Their involvement in subsistence activities is mandated from an early age, teaching them the value of contributing. The point when a child learns to do for himself and contribute to the household has a name, chape, (literally, “to escape”)

At five to eight years of age the child will chape, for it is at these ages he/she begins to go by himself to the water, start a fire, wash clothes, tend animals, find food in the garden, and go alone to make small purchases in the market. (Schwartz 2009: 160)

This “socialization for scarcity” inculcated in children is, Alvarez and Murray argue, the foundation for a carefully regulated and adaptive system of reciprocal exchanges among adults. Meals are portioned out based on recipients’ contributions to getting the food to make the meal and, in this way, household survival. Cooked food is shared with non-household members as pay for services associated with food or performed at a moment that crosses a meal time. Women strategically send food to other households and to individuals capable of and likely to reciprocate at a later date, something Alvarez and Murray equate to “money in the bank,” i.e. a means to negotiate periodic food scarcity. The strategy does not increase the total food supply, as the authors observe, but spreads food out in time and space. This levels out need and reinforces each individual’s contribution to the food supply—i.e. adults are rewarded with meals for productive behavior (ibid section 12: 189 – 192). The sharing of meals between households is such that in a 2017 random sample of 451 households in the rural Grand Anse, Haiti, we found that fully 57 percent of respondents reported “always” sharing meals with people living in households more distant than the confines of the yard; 43 percent had in fact sent a meal to another house within the past 24 hours of the interview and 35 percent reported having received meals from another household within the previous 24 hours. Overall, 37 percent of those who received food were not family of the person who sent it (see this paper).

Socialization for Scarcity: Household Level

The rural Haitian household is a consumptive unit organized around the preparation, consumption, and sharing of meals, but in terms of understanding the households, why they exist, the rules that regulate them, and how and when they cease to exist, it is more useful to think of them primarily as productive units.

A household in rural Haiti comes into existence as a result of an informal but very real contract between a man and a woman, a contract that serves as the foundation for household productive organization. The man must provide a house for a woman; then he must continue to provide money or to cultivate gardens and care for livestock; the woman must provide children; she manages the household, directs the labor activities of the children, processes and sells the products of the household in the market and engages in other marketing activities that will extend the buying power of the money. In this way the actual house can be thought of as the material focal point of a productive—albeit also consumptive–enterprise staffed by people, i.e. the family and other members of the household.

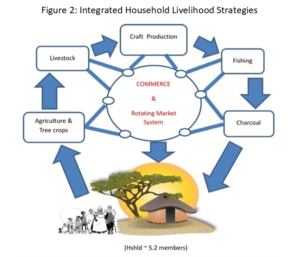

Household Productive Strategies

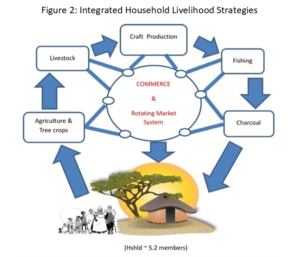

Few if any households in rural Haiti depend on a single production strategy. Cropping strategies, opportunistic fruit harvesting, livestock rearing, and charcoal production are the mainstays of the household. Agriculture is primary. Essentially all rural households depend to some extent on the inter-cropping of sweet potatoes, yams, manioc, and plantains. These crops are known as viv, and with the exception of sweet potatoes, they are available year round and during the most severe crises. The farmers also plant corn and beans, peanuts, melons, squash, and peanuts. Emphasizing the persistence and adaptability of the subsistence orientation of this livelihood strategy, five of the major crops are the very same five crops most important to the Taino Indians who inhabited the area in pre-Columbian times (manioc, sweet potatoes, corn, peanuts, and pumpkin).

The second pillar of the regional economy is livestock. As common as crops, at any given time 90 percent of rural households have at least one chicken, 80 percent will have one to five goats, 50 percent will have at least one pig and/or cow, 20 percent will have a pack animal (donkey, mule, or horse). Where fertile agricultural plots are common, livestock must be tethered and strict penalties are to be paid for those whose animals ravage their neighbor’s gardens. In more remote communities where the land is dry and less productive, typically area where State owned land is common, people free range their livestock.

The third pillar is manufacturing charcoal for the urban market, a major productive activity for many low-income rural households and the most important economic backstop in times of crisis.

A fourth pillar of the domestic economy, less important in term so income but very important in terms of nutrition, are products fruit trees. Virtually all rural Haitians either own or have access to at least several of 18 fruit and nut bearing trees that provide an almost constant yield – of at least several fruits– throughout the year and that include staples such as breadfruit and avocados. Sources of cash are coffee, cocoa and coconuts. Management of trees is largely opportunistic in the people in rural Haiti only sometimes deliberately plant trees. More often they nurture trees that have sprouted on their own.

Fishing is important activity for members of 10 percent of rural Haitian households. There are very few full-time fisherman in Haiti. It is more often an income generating and food procurement activity complementary to the strategies described above and is almost always artisanal, meaning simply in terms of technology and strategies and low yield (see this report).

Also important are crafts and skilled labor activities. But these activities too tend to complement those discussed above and very few rural Haitian households depend exclusively on them.

Simplistic Technologies and Near-Zero Risk Zero-Investment Strategies

The tools used in performing the livelihood strategies discussed above are, for the vast bulk of the population, no more complex than picks, hoes, and machetes. Animals are free-ranged, tethered to bushes with rope. Few farmers use barbed wire; rather, gardens, homesteads, and the rare corral are enclosed with wooden stick barricades or living fences made of fast growing and malicious vegetation such a dagger-like sisal, cacti, and poison oak (katoch, kandelab, pit, pigwen and bawonet). There are few pumps; farmers with gardens plots near to springs and rivers sometimes manually haul buckets of water to irrigate crops, particularly vegetables in cool highland areas. Irrigated land is scarce (less than 2% of all agricultural land). The use of chemical or processed fertilizers and pesticides is almost entirely confined to highland vegetable gardens and, to a lesser degree, beans (also considered a cash crop), that dependably yield profits. Many houses are made of local stone or waddle and daub and roofed with plaits of zeb guine (Guinea Grass) or thatch from native palms. With regard to fishing: the prevailing technologies are rowboats, bamboo fishing traps, and string nets. In most of Haiti, farmers do not use cows or horse traction to plow fields.

Household Organization of Labor Activities

The de facto household head is often the woman of the house. Men are often away, working on distant gardens, or at itinerant labor activities. Indeed, the man is expected to pursue occupations outside the household and leave the daily maintenance of a productive household to his wife. She will organize the labor activities of its members —mostly children—to accomplish activities such as retrieving water, searching for firewood, moving animals, washing clothes, and making the afternoon–the latter being no small chore in rural Haiti where there is not refrigeration and most foods, such as rice and beans, must be processed and cooked for long hours.

Children who do not conform to the work regime are severely punished, commonly with violence, something not surprising when one considers that failure means scorn from neighbors, shame, hunger, illness, and ultimately the dissolution of the household itself and the scattering of its members. As the children get older the woman is freed to begin engaging in her own itinerant activities, specifically long-distance trade, as discussed below.

Rural Haitian households are linked through real and fictive kinship ties (the latter primarily being godparentage). They are linked through reciprocal agricultural work groups, religious communities, and through inter-household reciprocal exchange of meals seen in the previous section. But perhaps more importantly than anything else, rural Haitian households are linked through participation in a vibrant and intensely integrated marketing system that has roots in pre-Columbian and colonial economies.

Socialization for Scarcity: Societal Level

Internal Rotating Market System

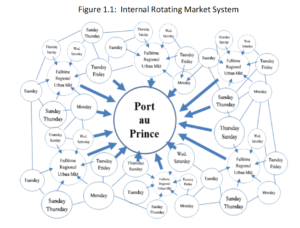

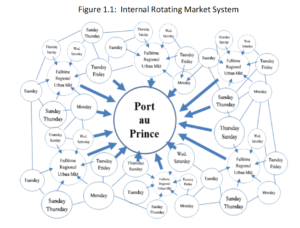

The household organized Agricultural-Tree-Livestock- Charcoal livelihood system described above comes together in the Internal Rotating Market system. Throughout Haiti, open air markets occur on alternating days of the week such that people living in any given region have walking distance access to at least two markets per week (see Figure 1.1 below). Montane micro-climates, their differing rain patterns, and the consequently differently timed harvest season make it logical for farmers to sell their crops rather than risk losing them to insect and mold and then store surplus in the form of money. The opportunity has facilitated the evolution of the intense interregional trade dominated almost entirely by women, the machann and madan sara.

Female Dominated Market System

The system is such that women may sell daily small quantities of items produced by the household- such as eggs, manioc or pigeon peas. But the prevailing strategy is for one woman to seasonally specialize in a particular item, such as limes, buy small quantities from multiple farms, accumulate a profitable quantity, and then take them to market or sell them to another intermediary higher up the chain, one more heavily capitalized, who accumulates greater quantities and who is likely destined for a larger town market, city or, the holy grail, Port-au-Prince.

The trade activity of women is a critical part of the household survival strategy. Rare today is the household that does not have at least one female member who purchases goods in the markets for the household consumption, sells products of the household in the markets, and buys and resells the products of other households in these markets. The best way to conceptualize the money from sale of household produce and female marketing activity as a medium of storage, one in which consumption of the stored household surplus can first be sold and, secondly, the surplus prolonged by rolling the cash it yielded over in the market, producing petty profits.

Subsistence Orientation

A critically important point for the analysis and understanding socialization for scarcity at the market level is that while the household is oriented toward production for the market, it is emphatically not oriented towards “wants,” but rather subsistence and local production. The overwhelming bulk of products found for sale in the market are inexpensive, locally produced and somehow related to production and subsistence; with respect to the profits that the machann earns, the bulk of the money is destined for reinvestment in commerce, other income generating enterprises – such as fish traps – or spent on subsistence foods and necessities for the household and, ultimately, the growing ‘mama lajan‘ (literally “mother money,” or more technically, the principal or capital) preserved for economic recuperation during times of crisis.

Artisan/Craft Economy

The market system bleeds over into a burgeoning economy of micro-producers, service specialists and petty vendors including porter, butcher, baker, tailor, basket maker, rope weaver, carpenter, mason, iron smith, mechanic, mariner, boat maker and host of marine specialties that keep the boats afloat. Micro vendors from the most remote homestead to the towns and cities sell everything from a single cigarette and shot of rum to telephone recharge cards to hair ties to small bags of water to cures for cancer and unrequited love and bad luck or dozens of different lottery tickets.

History and Context in which Socialization for Scarcity Emerged

Alvarez and Murray assert that “Socialization for Scarcity” is the recent consequence of a “deteriorating rural economy,” but there is reason to believe that neither food scarcity nor the strategies for coping seen above are new. Indeed, they are best understood precisely as an adaptation to scarcity brought on by periodic political upheaval and natural disaster that goes back two centuries.

Specifically, Haiti’s colonial history was marked by 100 years of slavery, when the slave ancestors of Haiti’s contemporary majority had no other choice than to plant their own subsistence crops. This period ended with a 13-year struggle for independence that was arguably per capita the deadliest conflict in human history, with about half of the civilian population perishing in combat, or from disease. Social upheaval and internecine warfare continued through the 19th century, with more than 25 wars and uprisings, and 60 years of international trade embargoes. The 20th century brought an equal number of violent conflagrations and embargo that have continued through the first 19 years of the current century. And that’s just the violence and social upheaval.

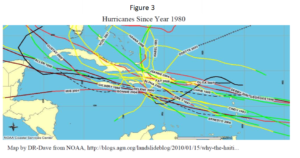

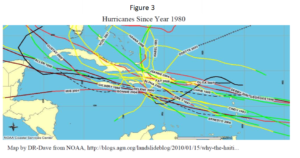

Since 1851, Haiti has been hit with at least 22 hurricanes and 29 tropical storms–one severe storm every 3.7 years. The storms periodically ravage crops and kill livestock. Droughts, some of which last a year or more, can cause even greater damage. In some areas, severe droughts strike as often as 1 in every 8 years. More recently (2010) Haiti was hit by one of the most devasting earthquakes in human history. In 2018 1/4th the country took the full brunt of one of the most devastating hurricanes in human history.

The upshot is that people in rural Haiti live on the juncture of multiple geological fault-lines, smack in the middle of the Western hemispheres hurricane belt, surrounded on three sides by water and on the remaining side by a neighbor who in the living memory of some Haitians dispatched convicts, prisoners and military attaches to massacre with blades and in the space of three days 25,000 of those Haitians living on wrong side of the border. The cause of these natural disasters and human calamities is a moot point. The relevant point is that the population has had little choice but to adapt. They have done so by cultivating dependency on those forces they can control: hence the technologically simple and integrated production, processing, and marketing strategies seen above.

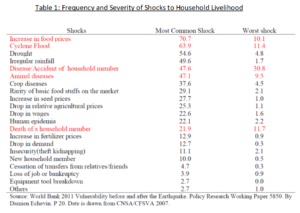

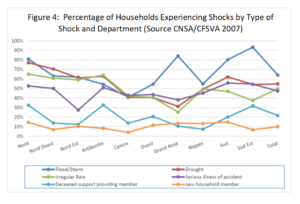

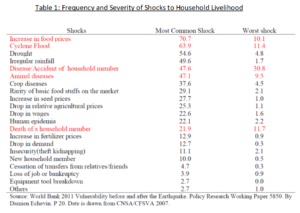

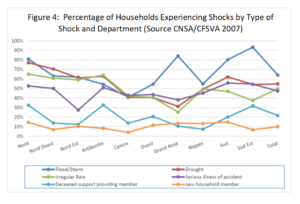

Adding to the difficulty of storing crops, erratic weather patterns, political upheavals, and economic isolation–indeed a consequence of it all—are restricted access to industrial technologies, a poor medical system, and weak agricultural extension services, all of which make epidemics for crops, animals and people more common and more severe. The consequences of crop and livestock losses are obvious. A family can watch its social security literally wilt and die in weeks, or even days. A family can face perhaps greater devastation from human illness—a mother who earns vital income from commerce, or a father who cares for the household’s animals and gardens. Sickness mean not only lost labor and income from that labor, it also means medical bills that cause a sell-off of livestock and land, thereby deepening vulnerability. The significance of these crises is such that in a 2007 CNSA/CFSVA survey, three of the five most common shocks respondents reported in the previous year were intra-household: specifically, accident/illness, death, and animal disease (Table 1). The most common type of shock was “Increase in Food Prices,” reported by 70.7% of respondents. This was 2007, a moment in time during the rising world food prices that climaxed in the 2008 world food crisis. But disease or accidents suffered by a family member were three times more likely than prices to be identified as the worst shock suffered by the household in the preceding year. As with hurricanes and droughts, the country’s medical system has always been inadequate. When the US Marines invaded Haiti in 1914, the US Navy Medical Director of Public Health, Captain Kent C. Melhorn, described ‘the whole country as teemed with filth and disease” (Heinl and Heinl 1996: 452).

The food consumption patterns and livelihood strategies we see today stem from more than two centuries of adaptation. Haitians have always faced frequent and extreme environmental, political and economic shocks, and they negotiated them by cultivating dependency on those forces they can control. They developed or clung to technologically simple and integrated production and processing strategies seen above. They invested social capital in a system of household interdependence and the ‘socialization for scarcity’ that Alvarez and Murray so carefully described 35 years ago.

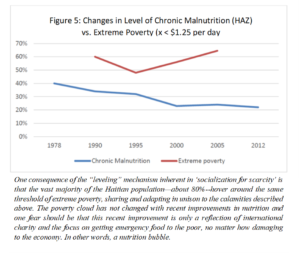

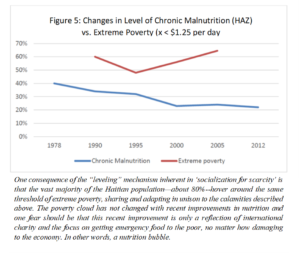

But while Alvarez and Murray may have erroneously asserted that “socialization for scarcity” is new, they were certainly correct in asserting that there have been declining yields and increasing economic stress. While this is not the place for an extensive elaboration, undergirding the declines are environmental degradation, 30 years of political instability, the concurrent flood food aid into Haiti (read this and when you’re done, read this), and a corresponding lack of innovation in agricultural production technologies. At the same time—if not because of these declines–the last half of the 20th century was a time of juggernaut urbanization and a corresponding increase in the role for the formal economy.

Conclusion: Models for Understanding

Arriving at a holistic understanding of the dynamics behind vulnerability in rural Haiti and the phenomenon that we are here calling socialization for scarcity the crux of the argument is that the household as a productive enterprise is the principal mechanism for individual social security in rural Haiti; extra-household social capital is a secondary safety net; and inter-household interdependency disseminates out primarily along the axes of biological and fictive kinship. The role of the household and inter-household relationships are conditioned by opportunities made possible through Haiti’s highly integrated rotating market system and they rest on autonomous productive technologies necessary in the near total absence of effective information systems (extension services and market information), transport systems (roads, trains, and powered shipping), and administrative technologies (regulatory legal systems), the sum of which make the conditions confronting people in rural Haiti resemble, not contemporary conditions for small farmers found elsewhere in the region today, but conditions found in centuries past. All the preceding can be understood as a response to rural Haiti’s rather unique configuration of historic and current constraints that include an unusually harsh and unpredictable natural environment seen earlier, one characterized by severe storms and frequent drought, and not least of all Haiti’s historic role as rebel black republic among, until recently, officially racist counter nations, something complemented by frequent embargoes, internecine domestic politics subsidized by international special interests, economic and social isolation. Thus, we can conceptualize Haitian adaptation as the three tiered model socialization for scarcity at the individual, household level and societal levels.

Readers may be also be interested in these other post regarding household resiliency and livelihood studies in Haiti:

WORKS CITED

Alvarez, M.D. and Murray, G.F. Socialization for scarcity: Child feeding beliefs and practices in a Haitian village. United States Agency for International Development

Heinl, Robert Debs, and Nancy Gordon Heinl. 1996. Written in Blood: The story of the Haitian people. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2009. Fewer Men, More Babies: Sex, family and fertility in Haiti. Lexington Press. USA

World Bank 2011 Vulnerability before and after the Earthquake. Policy Research Working Paper 5850. By Damien Echevin. P 20. Date is drawn from CNSA/CFSVA 2007.