This post deals with defining the concept of a “household” and a member of a household in Haiti. But before launching into an exploration of the problems with the household as a unit of analysis, some readers may be more interested in other topics regarding household studies in Haiti and can refer to these posts:

When defining just what constitutes a “household,” humanitarian aid experts working in Haiti typically emphasize lodging, a certain amount of time in the lodging, sharing of food, and mutual recognition among members of the same household head. For example, the official source for the definition of the Haitian household is the parastatal food security organization CNSA (Coordination Nationale de la Securite Alimentaire) and its donor-partner WFP (World Food Program). Here is how they define the household,

A household is defined as a group of people, with or without blood relation, who have been living together in the same lodging (under the same roof) for at least six months—or who have the intention of remaining in the household–and who share food and recognize the authority of the same household head (man or woman). CNSA/WFP 2015

The definition is logical from the perspective of emergency food aid. It specifies the household as an exclusive group of consumers, residing at a specific location; perfect for distributing aid. The concept is also useful as a sample unit: surveyors can readily identify the physical structure of a household and then inquire about those who sleep and share meals within it. But there are problems with every aspect of the definition, from lodging, to meal sharing, to the notion of household head, to the very conceptualization of a building structure corresponding to the social configuration of a “household.” This latter point–the use of the same word “household” to define the physical structure of a house and also to define the relations of people who use the structure–might be part of the confusion. But whatever the case may be, failure to appreciate the weaknesses inherent in the definition leads to a misunderstanding of how people in rural Haiti cope with crisis, which is why I am taking up the issue up here.

In this post I elaborate on five points,

1. Rural Haitians can and often are members of more than a single household.

2. Rural Haitians who sleep and eat in the same confined physical space (a house, apartment or room) do not always conceptualize themselves as a single residential unit, nor do they always share meals.

3. Rural Haitians who live in multiple houses in the same yard, can and often do behave as one consumptive unit, i.e. they share meals

4. Rural Haitians who live in entirely different yards quite frequently share meals.

5. Who is considered the head of their household often depends on who you’re asking.

6. A rural Haitian household is better understood as a unit of production rather than consumption.

1) Rural Haitians can and often are members of more than a single house

Everyone in any given household can and usually does live and share meals in multiple houses. For example, many rural families have garden house, a house in town and one in a nearby city. These houses may have separate owners or ‘household heads,’ different members, or they may share members and be inhabited mutually by an overlapping flow of the same adults and children, such as children going to school, some of whom spend the week in town but weekends and vacations at the rural homestead. Similarly, itinerant market women transporting goods to town or the city for sale, and men who work part time in the city may be members of multiple households.

While we do not have specific data, we do know this anecdotally. For example, in the first farming community I studied in Haiti, one in which I lived periodically over a period of a year and that I have followed over the past 29 years, I cannot think of a single one of the 59 households in which members were not also members of a household in the nearby village of Mare Rouge where the children went to school, women plied their trade on market day, and men sold their livestock. In the second community I lived in and where I remained for an uninterrupted period of 15 months and followed closely for 5 years, at least half of residents had a second house home in the nearby village. Moreover, all the above people were likely to also participate in households in Port-au-Prince where many of the older children would go to school and where market women would take produce for sale in the more lucrative metropolitan market places.

A common practice that also complicates the conception of single household membership is polygyny and analyzing and understanding the household as the unit of analysis is the polygynous rural Haitian man. Polygyny in rural Haiti is significantly different from the “extramarital affair” and the “mistress” in that, 1) it is recognized by the community, 2) efforts are made to produce children in all of the unions, 3) the man provides a home and the capital necessary for his wife to engage in marketing activities and to invest in productive, labor-intensive activities centered around the household (working for wages, planting gardens and/or tending livestock), and 4) the woman/women are expected to remain sexually faithful to him (elaborated from Murray et al. 1998). The type of traditional marriage that makes polygyny possible is not sanctioned by the church and there is no legal registry for the union being described, but it is in fact legally recognized by judges in Haiti as a type of common-law marriage. It has a common name (plasaj). There are also multiple names that designate the relationship of the women engaged in union with the same man (koleg, matlot and rival). It does not matter if the man is legally married to one of the women or not. The only limit on the number of women in union with the man is his financial resources to invest in homesteads, the animals and gardens necessary to maintain a productive household, and to invest in each of the “wife’s” commercial activities.

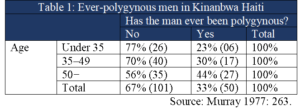

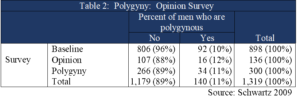

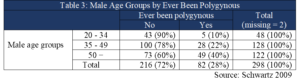

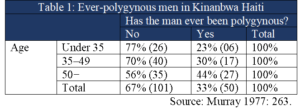

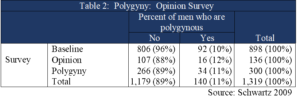

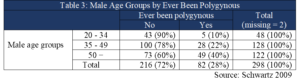

Polygyny is common in rural Haiti. Murray found that in the rural Haitian community he studied, at any given moment in time 11 percent of all men no longer living in the home of their parents were engaged in a conjugal union with more than one woman and 56 percent of all men over the age of 50 years had been polygynous at some time in their life (see Table 1). In my own studies, in Northwest Haiti I found almost the exact same thing. Eleven percent of adult males I surveyed were polygynous (see Table 2). When I looked specifically at men in high-income groups, the incidence of polygyny dramatically increased: 33% of skilled workers were polygynous, as were 44% of spiritual healers, 27% of male school teachers, and 62% of fishermen. Farmers with relatively large landholdings also displayed a tendency to have multiple wives (20%). Moreover, as seen with Murray’s data, polygyny increases with age: 45% to 50% of the rural men in my sample who were over the age of fifty had been polygynous at least once in their lives (see Table 3). What this means is that 11 percent of men are members of two or more households.

2) Rural Haitians sleeping and eating in the same physical space (house, apartment, or room) do not always conceptualize themselves as a single residential unit, nor do they always share meals.

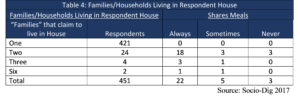

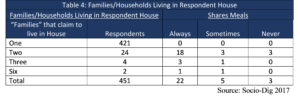

In 2017 Grand Anse random survey of 451 rural respondents, 30 claimed that more than 1 residence was occupying (7% of the sample); 22 of those respondents subsequently said that the different residences “always” shared meals, thereby suggesting that by the CNSA/WFP definition of meal sharing 8 (2 percent) were not part of the same household. Only three of the 30 respondents reported that the multiple residences “never” shared meals (see Table 4), suggesting that people who share close space of the household do tend to share meals. As seen below, a greater complication regarding meal sharing is that they often include people in other households.

3) Rural Haitians who live in multiple houses in the same yard can and often do behave as one consumptive unit

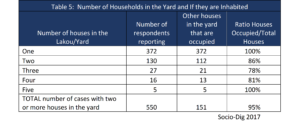

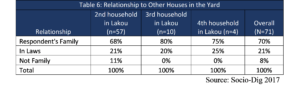

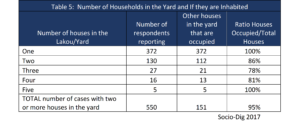

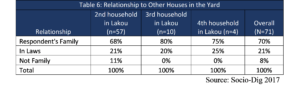

In the 451 household Grand Anse survey cited above, there were 151 cases (33%) where two or more households occupied the same yard. In 151 of those cases the other houses were occupied (see Table 5); 70 percent of those in the other houses were direct family of the respondent, 21 percent were in-laws, and only 8 percent were non-family (see Table 6).

While we did not ask in this particular survey whether households share meals, it is certain that many do in fact share meals. We know this anecdotally, from experience, and we can infer it from data on meal sharing between households not in the same yard, as seen in the following section.

4) People who live entirely different yards quite frequently share meals

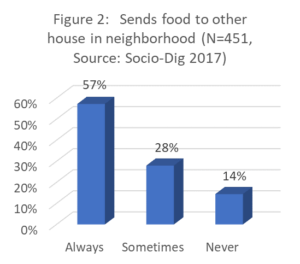

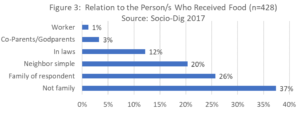

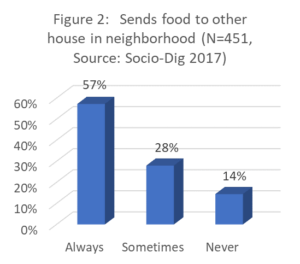

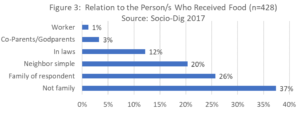

In the 451 household Grand Anse survey, 57 percent of respondents reported “always” sharing meals with people living in households more distant than the confines of the yard (see Figure 2); 43 percent had in fact sent a meal to another house within the past 24 hours of the interview and 35 percent reported having received meals from another household within the previous 24 hours (Figure 1). Overall, 37 percent of those who received food were not family of the person who sent it (Figure 3).

5) Who is household head depends on who you’re asking

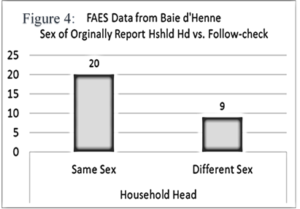

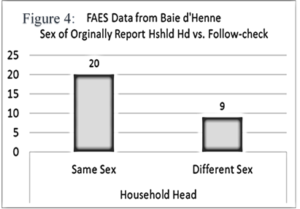

In the CNSA/WFP definition at the beginning of this article, a members of the household were defined as identifying the same household head. But who is the head of a household is not always clear. For example, in a 2013 FAES data collection in the North West commune of Baie De Henne, surveyors set up kiosks in 4 habitations (townships) and asked respondents, among other questions, who was head of household. One year later we re-visited 29 of those households and asked the same question. In nine cases (31%) the sex of the household was different than originally reported. In all nine of those cases the response came from someone different than the original respondent. In other words, different household members cited different household heads (Figure 4). Part of the problem derives from the fact that for many people in Haiti, particularly rural areas, households tend to be de facto female headed. Whether a man is present or not and whether the man reports he is running it or not, women in rural Haiti tend to be the daily household decision make. Women typically control the household budget and they are the primary disciplinarians of children. This is not a supposition. It is simply a fact of rural life in Haiti. The trend is such that a common refrain in rural Haiti is that gason pa gen kay (“men don’t have house,” i.e. because women own them). The point is borne out by surveys indicated that women make 50% or more of the household decisions without the participation of their spouse (EMMUS (2012; 2005; CARE 2013, Schwartz 2009, Murray 1977). That said, if you ask men and women who the household head is, they are both more likely to tell you that the household head is the man.

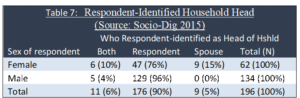

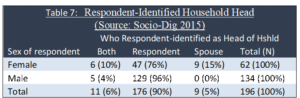

For example, in a 2015 survey of Grand Anse Cacao producers, the majority of self-identified household heads were men (Table 7). Specifically, when asked, 76 percent of women identified themselves as the household head vs. 96 percent of men.

Thus, men are clearly more inclined to self-identify as the household head. Similarly, women are more inclined to identify their husband as household head: nine women (15 percent of the sample), identified their husband as the household head. No men identified their wife as the head of the households.

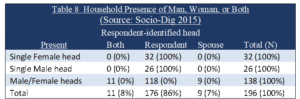

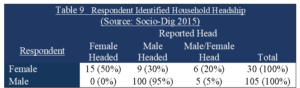

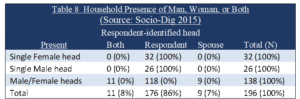

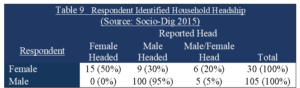

The trend is even more pronounced if we control for those households with no man at all (Table 8 tallies the number of single male and female headed households vs. those with both a male and female couple in the house). Of the 30 women who were asked who the household is and who in fact have a husband living in the house, in 6 cases she identified both herself and her husband as the head, in 9 cases she identified her husband as household head, and in 15 cases she identified herself as head (Table 9 ). That means that of those respondents who were interviewed and who had a husband in the house, ½identified themselves, rather than their husband the household’s head.

For men, of the 105 households with both a male and female in them and that a male respondent could have chosen himself, his spouse or both as household heads, in 5 cases the man chose both, in 0 cases they chose their spouse, and in 100 cases they identified themselves as the household head (see Table 9).

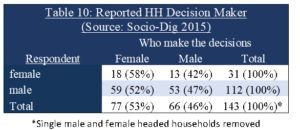

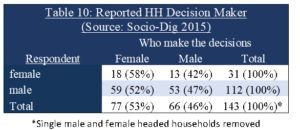

The rather strong suggestion is that, had women been interviewed we would have gotten a very different response profile. Moreover, there is the influence of different gender regimes based or differential presence of men vs. women. Where adult males are not present or scarce women take on tasks that would other wise fall to men. Another possibility is that the surveyors had their own prejudices that influenced responses. In fact 7 of the 9 women who identified their spouse as household head were interviewed by the same surveyor. Either way, a much better means to determine who is “head of household” is with the question, “who most often makes the household decisions regarding expenses.” This question yields more consistent results from both male and female respondents and show that women slightly more than men tend to be in charge of the household (see Table 10).

6) A household is better understood as a unit of production rather than consumption

The CNSA/WFP definition seen at the beginning of this article emphasizes the household as a unit of consumption: members of the household share space and meals under the authority of the same head. But there is no mention of cooperative production or labor contributions. The reason is because CNSA and WFP are humanitarian aid agencies both entities focused on food security and in the contemporary US supported priorities, that means giving food away and hence seeking to identify recipients of aid.. But a great deal of insight can be garnered from looking at rural households in Haiti, not so much as a unit of consumption, but one of production.

All households in rural Haiti function as productive units. People living in the household work at an array of productive endeavors, typically including agriculture, livestock rearing, fishing, charcoal production, harvesting of fruit from trees, and artisanship. Even very young children make significant contributions to the household if not doing these productive activities, then at least performing activities that free the adults to engage in such activities. Specifically, preparation of meals, washing clothes, retrieving water, and keeping the household clean and sanitary. Indeed, children tend to comprise the bulk of the labor pool of households (see Schwartz 2009). The woman of the house is typically responsible for orchestrating the day to day labor activities of the children. Those children who do not conform are severely punished, commonly with violence, something not surprising when one considers that failure means scorn from neighbors, shame, hunger, illness, and ultimately the dissolution of the household itself and the scattering of its members.

Failure to appreciate the primacy of production as a determinant of the households, means that analysts will failure to anticipate how households in rural Haiti react to crisis and, hence, how to most effectively intervene to assist them. Indeed, it may be that intervening to save the household has long term detrimental consequences. When a household faces an internal crisis that it cannot overcome, i.e. when it can no longer maintain productivity, it breaks up. Members rely on their personal safety nets. They go to live in other households, with other family; or they migrate; the household may even reconstitute itself elsewhere. Children, the greatest concern for most socially conscience aid workers, are readily incorporated into other productive households as highly prized contributors to the labor pool, so much so that true orphans are almost impossible to find in Haiti such that “orphanages”– that thrive on donations for “orphans” –are typically stocked with children who have parents, and in many cases middle class urban parents (see Schwartz 2012). Thus, aid that encourages the continuation of a no-longer productive entity, will inevitably create a population of households that become dependent on aid from NGOs and the State, aid we might add that is fickle at best. With this point in mind, I finish this article with three insights regarding the household that I believe are critical to understanding how rural Haitian households function.

Works Cited

Gerald F Murray, Matthew McPherson, and Timothy Schwartz. 1998. The fading frontier: An anthropological analysis of the agroeconomy and social organization of the Haitian-Dominican border. USAID Report.