Picture is from Jeanty Junior Augustin/Reuters

In this post I try to make the situation in Haiti understandable by identifying nine critical historical and contemporary processes that condition the current crisis.

| 1. Class Schism | 6. Urbanization |

| 2. Rural/Urban Divide | 7. Centralization |

| 3. Internal Rotating Market System | 8. Emigration |

| 4. Political Instability | 9. NGO Invasion |

| 5. Extreme Poverty |

1. Class Schism

Haiti was the second country in the western hemisphere to have broken free of colonial European rule and the first free republic in the world governed entirely by descendants of African emigrants, many of whom had been slaves. But it was not the product of a single victorious revolution. It was the victory of two revolutions and the aspirations of two very different populations. On the one hand, 200,000 almost entirely illiterate former slaves, at least half of whom had been born in Africa. On the other hand, a population of some 20,000 mostly mixed-blood European-Africans with western values, many of whom, prior to independence were European-educated and landed elites, plantation and slave owners. Two distinct populations identifying with two very different cultural traditions: French vs. West African. Practicing two very different religions: Catholicism vs. Voudou. Producing for two very different type of economies: plantation production oriented to the global economy vs. small scale peasant production for the local market. Having, for the most, two different skin colors: one light and the other dark. And speaking two different languages: French vs. Kreyol (albeit all spoke Kreyol while the elite also spoke and prioritized French). The division was such that, a century after the revolution, the renowned Haitian intellectual Jean Price-Mars would describe these two classes as so separate that they came to form, “two nations within the nation, having each its own interests, its own tendencies, and its own ends” (see Shannon 1997:43). Yale sociologist James G. Leyburn (1941) would go even further saying “that the only terminological concept adequate to describe the extremity of economic, religious, cultural, and color divisions between Haiti’s masses and its elite is ‘caste’” Prou (2009:31) summed up the division as a type of “Social Apartheid.” Throughout Haitian history, each side has had its own heroes, its own flag, and its own political parties. A consequence of this class polarization is radically differential access to wealth, today manifest in the third highest GINI Coefficient in the world (Figure 1, see also CIA 2020).[1]

2. Rural/Urban Divide

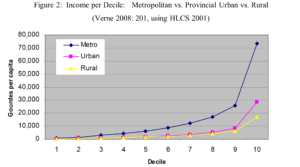

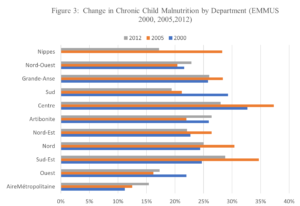

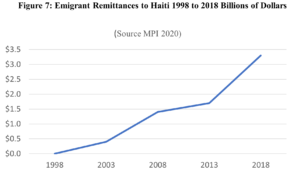

From independence until the 1950s, when still some 85 percent of the population lived in rural areas, and still to a large extent today, when 45 percent of the population is still living in rural areas, the division described above has correlated closely with moun lavil (city folk) vs. moun andeyo (people “outside” of the city). Whether or not people live in the town vs. rural area or metropolitan Port-au-Prince is the only significant geographical feature that sets one segment of the Haitian population off from another. People in the rural areas in Haiti are significantly more impoverished than the urban populations, a fact illustrated by the data in Figures 2 and 3 showing the dramatically higher income and nutritional status of the urban, largely slum populations of metropolitan Port-au-Prince vs. the rest of the country. Underlying this difference is that urban populations are linked to and in large part dependent on the global economy, not least of all through relatively high level of remittances sent by Haitians living and working overseas (see Figure 7, Remittances, in below section Extreme Poverty), while rural populations continue to depend on what are predominantly stoneage subsistence strategies.

Haiti is an unpredictable and harsh economy and natural environment in which to be a farmer. Smack in the middle of the Western hemisphere’s hurricane belt, Haitian producers can expect to be hit by one tropical storm or hurricane every 3.7 years. In some areas a severe drought strikes 1 in every 8 years. Adding to their woes are riots, protests, military conflict, and international embargoes that have been a near constant feature of life since the Haitian ancestors began the struggle for freedom 231 years ago.

There is almost no escape. The country is surrounded on three sides by sea that is patrolled by US coast guard cutters that confiscate, sink and/or burn Haitian migrant boats and repatriate hopeful emigrants. On the remaining side live the Dominicans, Haiti’s militarized neighbor. A defining historical moment was a 1937 massacre of 25,000 ethnic Haitians living throughout the Dominican Republic, after which migration of rural Haitians into the Dominican Republic was limited for some 50 years to formal migrant labor programs managed by the Dominican and Haitian militaries whereby the Haitian government rented rural Haitians laborers to the Dominican State-owned sugar plantations. The massacre notwithstanding, the near total suspension of Haitian migration following the massacre had more to do with limitations imposed by Haitian army controlling the border than it did with Dominicans, a point evidence by the fact that, with the 1986 fall of the Jean-Claude Duvalier dictatorship and withdrawal of the Haitian army from the border, rural Haitians once again began migrating to the Dominican Republic in large numbers.

Since that time, rural Haitians have increasingly sought short and longer term employment as low wage laborers in Dominican agriculture, construction, and tourist sectors. The rural Haitian migrant is welcomed and given employment by those who benefit from their services, but they experience significant discrimination from other segments of the population. The prevailing Dominican view of low-income Haitians is that they are savages. Returning migrants are frequently and with total impunity robbed by border guards and local Dominican farmers. Dominican soldiers have periodically rounded up Haitians in repatriation drives and send them back to Haiti without allowing them to collect their pay or belongings.

For rural Haitian producers without the education and money to leave Haiti with a legal visa, the main alternative to staying in rural Haiti and farming is to leave their families behind and try their luck in the slums of Haiti’s cities. All this brings us to those who do stay in the rural areas. It is this milieu of constantly impending calamity and restricted migratory alternatives, that we must understand what it means to farm in rural Haiti, for despite all the donor money–not least of all that channeled through USAID–the only reason most rural Haitians are alive today is because of their own efforts.

At the heart of the rural Haitians efforts to survive is conformance to a maxim so consistent throughout the country that we can elevate it to a rule: near 0 risk and near 0 investment. This maxim gives way to four direct corollaries that have assured that Haitians survive and equally assured the failure of hundreds of past development projects and will determine the impact of any future interventions as well. These are:

- reduce risk by maximizing the variety of trees and crops the household depends on, with special attention to those that are

- as resilient as possible to drought, floods and blight and/or responsive to rain and that

- yield slowly for a maximum period of time—providing steady flow of food and income for the household– while, in conformance with minimum investment,

- requiring minimum inputs and maintenance

For at least 90 percent of rural Haitians, the above points are inviolate. Before investing in anything else—cash crops, trees, animals, education, or in many instances, even life-saving medical care — the Haitian small farmer first invests his or her time and labor in a large variety of resilient crops with priority going to those that mature quickly and yield for long periods, preferably year-round. [2] [3]

3. The Internal Rotating Market System

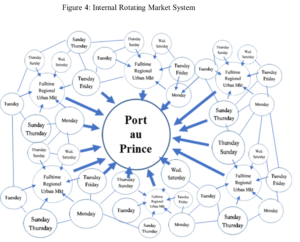

Any understanding of Haiti and especially an understanding of the current predicament of people living in rural Haitian is impossible to achieve without an appreciation of the internal rotating market system. The Haitian economy is dominated by vigorous internal rotating market system, the main system for regional redistribution of domestic produce and even imported goods. It is in informal but institutional, the most important redistribution mechanism in the country, such that, when informal roadside vendors are included, it is the point of sale for an 80 percent of all purchases in Haiti, even with respect to imported items such as toothpaste (see Schwartz 2019a). But what most concerns us here is the internal rotating markets systems role in the marketing and redistribution of rural produce, and hence the primary source of income for all rural Haitians.

Mountain micro-climates with differing rain patterns result in staggered harvest seasons. This has allowed for the evolution of intense interregional trade. Buying and selling is dominated almost entirely by women–revande (stationary resellers) and madam sara (itinerant traders). Household producers seen above sell to itinerant traders who move produce to local or larger regional markets. There, resellers market goods to local consumers or to other madam sara who move the goods up the line to fulltime markets in provincial urban area, and ultimately to the holy grail for all marketers, Port-au-Prince, which is now home to 1/3rd of the Haitian population. It is along this same channel—or channels close to it–that Haitian exports traditionally moved and that the few agricultural exports that still come out of rural Haiti (goat skins, cacao, coffee) continue to flow.[4]

The internal rotating market system consists of rural open-air markets. These markets occur on alternating days of the week, staggering the operations among towns in any given region. This gives most people throughout Haiti access to markets within walking distance at least two days per week. [5]

For the poor who participate in these markets—including rural households selling produce, and urban-based women purchasing items for resale—the system serves as a medium of storage. The stored household surplus can first be sold and, second, prolonged and even expanded by rolling over the cash in the market to produce petty profits. When periods of scarcity strike, the family begins to consume this money, and dip into other forms of household savings by selling off livestock, or making charcoal. From the perspective of consumers, it is this system that has allowed the urban lower, middle, and elite classes to survive the frequent disaster, embargoes, and civil insurrections that have plagued Haiti in the 200 years since independence.[6] [7]

For rural producers, the access to markets mean they practice a type of extreme monetization, dumping harvests on the market when storing them might result in income three times what they get at the time of harvest, and often daily selling small quantities of produce such as pigeon peas or mangoes. They sell off their front porch or by the roadside, but most importantly they sell in the market. In effect, rural Haitians are market oriented.

While market orientation may seem anathema to subsistence production and planting first and foremost for survival, it is not. The market system too fits neatly into the near 0-risk, 0-investment strategy described above. Haitians use the market as a type of storage mechanism. For those crops that are harvested over short period of time, only in the rarest of cases—such as nearly indestructible cashews—do they risk storage. Instead they reduce risk by dumping the harvests in the market. It is a radical but extremely common example of the near-0 risk maxim because other producers are doing the same thing at the same time–dumping their produce on the market—glutting the market and depressing prices. This means the small producer forgoes profits of from 200 to 300 percent that would otherwise come with storing the harvest and selling when the produce in question is scarce.

This practice of not storing produce consistently befuddles development practitioners who are promoting increased attention to cash crops. The agronomist and economist can easily calculate the doubling and tripling of income that will come from proper harvesting and storage. But for the producers it is a safer bet to dump the produce, eliminating any risk of losing the crop to insects, rot, rodents, or thieves. They then use the cash to make investments in buying and selling other produce thereby extending the life of the money. All the while they are rolling the money over, they use the profits and eventually the capital to meet subsistence expenses as well as expenses associated with education, medical treatments, and shaman/sorcery services.

In summary, we can say that rural Haitians may not be classic subsistence producers who eat what they produce, but they are emphatically subsistence-oriented market producers and the reason is because of the limitations imposed by the unpredictable environmental, economic and political calamity seen above. They must prioritize. But even this does not mean that Haitian producers are not interested in making money. And that brings us to another major point that USAID should understand in crafting any new rural assistance projects: the past 40 years and $300 million-plus of rural projects in Haiti targeting exports entirely failed (see this report). And the reason they have failed is the demand for food stuffs and critical products on the local market is so high in Haiti that the export market cannot compete.

4. Political Instability

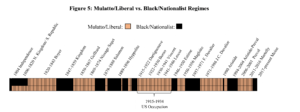

Haiti’s political history is largely one of a back-and-forth struggle between the two culture-classes described earlier, one in which the primarily urban and globally oriented elite supported by powerful business interests in developed countries would win control over the government for a decade or two and then be overthrown by populist primarily rural orient politicians representing the masses. One year after independence the country immediately split into two countries, a black kingdom in the north ruled by a former slave; and a southern republic in the south, presided over by a series of mixed-blood, former French military officers who had been born on the island. Perhaps ironically, the black kingdom was the more militarily powerful, more organized and more productive, a difference manifest in Haiti’s greatest monument, the mountaintop fortress Citadel Laferrière. But in 1820, internal dissent tore the kingdom apart. The southern mulattos immediately moved into the vacuum, seized control of the north and reunited the country. Thus began 200 years of struggle between the ‘castes.’

By mid-century social upheaval and internecine warfare aggravated by class conflict had become rife in the Haiti. Between 1843 and 1915, at least 25 wars and uprisings ripped through the country. Haiti had 23 presidents and 1 king during that period; 19 of whom lasted less than one year in office, only two finished their term, 14 were overthrown, two were murdered, five died in office from ailments. The early 20th century was dominated by the 1915 to 1934 US military occupation, fleeting moments of democracy overshadowed by 34 years of dictatorship, and then a return to violent conflagrations and international embargoes.

Chronic political turmoil has characterized the most recent forty years. From 1981 to 1986, violent popular resistance to the Jean-Claude Duvalier dictatorship rocked the country with protests, riots and national strikes. The dictatorship fell in 1986 and in the ensuing eight years were seven different regimes, two failed elections, two coups, and three years of military dictatorship that led to a UN military mission (UNMIH 1994-1996), two years of a foreign-assistance embargo (2002-2004), another coup (2004), another UN military mission (MINUSTAH 2004-2017), and then three years when gangs terrorized the population with armed robberies, home invasions, and kidnappings (2004 and 2007). In 2009, political stability seemed to be within grasp, in collaboration, with the Haitian government, the UN and USAID began orchestrating a massive, highly publicized investment strategy. Haiti’s elite entrepreneurs in Haiti, diaspora business people, and US billionaire social-investors were all on board. And then, on the 12th of January 2010, just as final touches were being put on the plan, an earthquake slammed the capital city of Port-au-Prince. Seven percent of all houses and buildings were immediately destroyed. Another 13 percent were damaged beyond repair. Typical to the disorder that prevailed in Haiti, no one knows for sure how many people were killed, somewhere between 50,000 and 316,000 (see Schwartz 2017 for a summary of studies on the earthquake death toll).

In spite of fallout from the earthquake, 2010 to 2015 was the calmest and most prosperous period in nearly a half century. Lending nations and international banks forgave the Haitian national debt, private donors gave NGOs some 4 billion US dollars in aid, foreign governments pledged more than $10 billion to Haiti. Poverty and struggle continued. Earthquake refugee camps persisted. But at the same time the country turned into a type of wonderland of development projects and foreign assistance. Expatriate aid workers seem to be everywhere. Restaurants and bars were packed with them. Roads were traffic-choked with their SUVs. Haitians from the diaspora poured back into the country. Compared to the decade before the earthquake and more recent years, Port-au-Prince was calm and prosperous (ibid).

But by 2016, most the aid money was spent and the country was slipping back into political instability and lawlessness. Since 2018, massive protests shut down transportation in Haiti for months at a time. Gangs once again took control of popular neighborhoods. In early 2020, kidnapping, home invasions and highway robberies were worse then they had been in 2004-2007. In the summer of 2021, the president was assassinated in his home. The current prime minister has been linked by New York Times journalists to the main suspect; it is widely believed in Haiti that he placed in power by the architects of the assassination (NYT 2022).[8]

Summarizing the impact of this political instability, since 2006, when Fund for Peace first began calculating its Fragile States Index–an indicator comprising activities such as state services, security apparatus, and human rights–Haiti has consistently ranked among the 13 most debilitated countries in the world, ranking among Somalia, South Sudan, Afghanistan and Chad.[9] [10]

5. Extreme Poverty

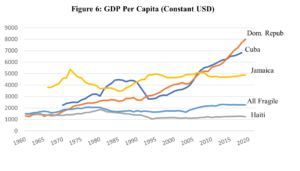

Haiti is one of the poorest countries on earth. In 2020 the UNDP Multidimensional Dimensional Poverty Index ranked Haiti at the lowest level of any country in the Western Hemisphere, with the 7th lowest standard of living in the world. But poverty in Haiti relative to other countries in the region has not always been as extreme as it is today. From 1967 to 1980, Haiti’s per capita GDP grew at a respectable average of 2.5 percent per year. Then, in 1980-81, precisely when the renewed political instability described above began, GDP stagnated. From 1986 until 1994 it moved backward, declining at a rate of 2.6 percent per year. Since 1995, the GDP at constant 2017 dollars grew 56 percent; but it is a figure that can be accounted for, not by increased production, but poverty itself. Specifically, the second highest rate of migrant remittances in the world, charity dollars given to Haiti as the West’s posterchild for poverty, money laundering, and narco-trafficking. A comparison of historic Haitian GDP with the neighboring Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Cuba illustrates just how dramatic this un-development has been (see Figure 6).[11]

6. Urbanization, Dominance of the Primate City

Haiti as a whole has gone from less than 10 percent urban in 1950 to 57 percent urban in 2020. A notable feature of urbanization is a focus on the metropolitan area of the capital city, Port-au-Prince. The city has grown at a rate 4 to 5 times that of other cities in the country, increasing in population from 133,000 in 1950 to 700,000 in 1980 to 2.8 million in 2020, an increase in size by a factor of 20 in the space of 70 years (see IHSI data). Today the city is eight times larger than Haiti’s second largest metropolitan area, Cape Haitian, with a population of 360,000 people. To put this in context of other countries, one third of the Haitian population lives in greater Port-au-Prince, ranking Haiti the 7th in the world in terms of the demographic domination of a single city.[12] [13]

7. Centralization

Whether a cause or an effect, lopsided urbanization seen above is associated with extreme centralization. Many provincial towns and cities that as recently as the 1950s had been thriving centers of regional commerce and political power have lost importance. Although also burgeoning with slums, these outlying cities have become relative backwaters as institutional headquarters have moved to Port-au-Prince. The 1987 constitution called for de-centralization and USAID-financed programs sought to decentralize the government and spread investments in development more evenly throughout the country, but with little impact. By 1990, 90 percent of Haiti’s exports and 60 percent of imports were going through Port-au-Prince; 80 percent of the national expenditures were made there; and today at least 95 percent of all foreign NGOs have their headquarters in the capital. Despite the rhetorical drive to de-centralize, Haiti today is among the most centralized countries in the world. A 2012 World Bank policy research paper rating 182 countries on both de jure and de facto indicators of political, fiscal and administrative centralization put Haiti 180th, 3rd from bottom on fiscal decentralization; 175th, 8th from the bottom on political decentralization; and 181st, 2nd from the bottom on administrative decentralization.

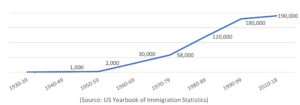

8. Emigration: Brain Drain

Haiti has experienced what is arguably the longest, most continuous, and intense brain drain of any country on earth. It began in the 1950s and 1960s when Rotberg (1971:243) estimates 80 percent of Haiti’s most qualified physicians, lawyers, engineers, teachers, and other professionals fled political persecution under the populist Francois Duvalier dictatorship. From 1980 onward, with the intensifying political instability described above, the numbers skyrocketed. At that time there were only about 150,000 Haitian emigres overseas. Today, there are at least ten times that figure: 662,000 people born in Haiti are living in the US in 2020, another 491,000 are in the Dominican Republic, 100,000 in Canada, 82,000 in France, and 69,000 in Chile (see Olsen-Medina and Batalova 2018). Totaled, the population living outside of Haiti is equal to 20 percent the population inside of Haiti, and that does not include the offspring of immigrants born abroad.

Many of those in the US, Canada and France are educated before they leave Haiti. No one has exact figures, but common in the literature are estimates that 80 percent Haitians with a post-secondary degree leave the country (illustrating how little is actually known about the situation, that figure comes from an International Monetary Fund study done 13 years ago: Prachi 2007). Summarizing the impact of this loss of human capital, on The Global Economy’s Human Flight and Brain Drain Index scale of 1 to 10—meant to estimate the intensity of the emigration of the educated—Haiti consistently ranks among the most impacted countries on world. In 2015, Haiti’s score of 9.3 was the very highest of all 176 countries rated (ibid).

9. NGO Invasion

Religious missions have been coming to Haiti since shortly after independence. Catholics were ousted during the revolution, but protestants sought to fill the gap. US Methodists arrived in the northern kingdom and British Methodists in the southern republic in the 1810s. US Baptists first arrived in the 1820s. In 1860 the government signed the Concordat with the Catholic Church, precipitating a flood of Catholic missions from Europe, complete with priests, brothers and nuns. In 1862 came US Episcopalians, Adventists arrived in 1879, and with the 1915 to 1934 US occupation the way for US protestant missions was wide open. Seventh-Day Adventist arrived in 1921, the Haiti Baptist Mission was established in 1934, Unevangelized Fields Missions came in the 1940s, Assemblies of God in 1945, Nazarean Church in 1948, The Salvation Army in 1950, the first Pentecostal church in 1962, the Mennonite Church in 1966, and the Church of God in 1967. More recently, Muslims founded the first Mosque in 2008 and have since become the fastest growing religion in Haiti.

Overlapping with the religious missions and ultimately subsuming them are NGOs and development contractors. Secular NGOs first began arriving in Haiti after Hurricane Hazel devasted the country in 1954. Their presence significantly increased three decades later in 1981. Precisely when the political chaos recounted above began in earnest, USAID decided to bypass what U.S. officials defined as “an extremely corrupt Haitian government.” US aid dollars were subsequently delivered either directly to the international NGOs or through for profit contractors such as Chemonics and DAI, entities that acted as accounting and oversight proxies, passing money onto NGOs and Haitian community based organizations. Some of the NGOs were the same religious missions seen earlier, such as the Haiti Baptist Mission. Others were re-incarnations or expansions of those earlier religious missions–such as Catholic Relief Services, Adventist Development and Relief Agency, World Vision, HEKS-EPER, and Lutheran World Relief. Others were secular—such as CARE International, ACDI-VOCA, ACF (Action Contre la Faim). The principal European donors—Germany, Britain, and France—followed the US lead, routing aid to NGOs and, in the words of Robert Lawless (1992), “Haiti soon became everybody’s favorite basket case.”

It is not clear today how many NGOs are in Haiti. Claims shortly before the 2010 earthquake ran as high as 10,000. As of 2012, only 561 had registered with the government (Valbrun 2012). A more realistic figure in 2020 would be closed to the 2,757 US-based NGOs in the country, an estimate that comes from US 501c3s that organizations in the United States have reported to the US Internal Revenue Service between approximately 2010 and 2020 (see Guide Star). Whatever the count, journalists commonly refer to Haiti today as “the Republic of NGOs.” And with good reason, whether it is healthcare, orphanages and child services, food relief, or environmental conservation, NGOs and organizations supported by overseas donations provide--prima facie– more services to the Haitian population than the Haiti State, a point, as seen below, abundantly in evidence regarding education. [14]

The presences of NGOs creates an internal brain drain even more severe than that of centralization. The most competent and competitive professionals are drawn away from State bureaucracies and national enterprises and into the foreign aid sector where wages are 2 to 10 times that found in government and private sector counterpart hospitals, schools, and agricultural projects. Many of these professionals then use the opportunity as a jumping off point to emigrate.

ENDNOTES

[1] Estimate for the GINI Index comes from the CIA (2020). It is based on their estimates from for all countries since ~2000. The estimates are not given for every year, but rather are made periodically. The estimate for Haiti comes from 2012.

[2] In areas where there is irrigation or high rainfall, the main crops are yams, plantains and taro, all crops that mature within one year, yield constantly over a period of several years, can be harvested green or left in the ground and harvested piecemeal any time needed. In dry areas they prioritize hardy, drought resistant crops such as manioc, which can also be left in the ground and harvested any time needed; pigeon peas, which yield slowly all year round; sugarcane, which has a tap root as long as 27 feet below the surface and can also be harvested as needed; sweet potatoes, which with as little as 4 inches of rainfall and in less than 6 weeks produces 12 tons of tubers per acre; or peanuts, a crop that can be grown in sand. The most important tree crops are all zero maintenance, with long periods of yielding fruit, such as oranges, mangoes, avocados, coconut, and arguably more important than any other tree crop, breadfruit, which yields something for all but a few months per year. Cashews are also an ideal tree crops, as they will grow in almost in soil, they are astonishingly pest resistant, drought resistant and produce high protein and high fat nuts that are nearly indestructible and can be stored for years with virtually no preparation other than being dried in the sun. Although much less popular, even cacao fits into this strategy, being essentially zero maintenance, while producing something all year round and with three peak seasons. It even propagates itself because seedlings readily sprout from those pods that rats open. Indeed, the reason producers do not simply tear cacao trees out of the ground is probably because it does fit into the strategy of 0-risk and 0-investment, while providing a significant source of scarce fat when needed.

[3] Somewhat ironically, The Haitian livelihood strategy being described is perfectly captured in what USAID defines as resiliency and in recent years has decided it is promoting. Specifically: The ability to minimize exposure to shocks and stresses through preventative measures and appropriate coping strategies to avoid permanent, negative impacts. (USAID 2017: 2)

Reinforcing resiliency has recently become a USAID priority. Similarly, as seen at the beginning of this documents, ILO’s priority with the present research shares similar goal of ‘equitable access to the means of subsistence, to productive resources, and to safe and decent work in order to reduce poverty in all its forms.’ Perhaps ironically with regard to the priority of exports, there is arguably no better description of the logical underlying rural Haitian livelihood strategies than USAID definition of resiliency. It is precisely, ‘the preventative measures and appropriate coping strategies to minimize exposure to shocks and stresses,’ that rural Haitians prioritize. Minimizing exposure to shocks and risks is deeply engrained in the culture and, in making USAID’s promotion of resiliency that much more ironic, it is this allegiance to resiliency that has for 40 years now, time and time again, vexed USAID, EU, and UN export-oriented development projects. If a project is to avoid the past pitfalls, it is critical to understand just why these strategies exist in the first place.

Note that above we are referring specifically to resiliency in terms of “absorptive capacity” as defined in USAID 2017.Enumerator Guidance: Full Model. A GUIDE FOR IMPLEMENTING A RESILIENCE MODULE, p. 2. Specifically,

Absorptive capacity: the ability to minimize exposure to shocks and stresses through preventative measures and appropriate coping strategies to avoid permanent, negative impacts.

The other connotations of resiliency as defined by USAID are,

Adaptive capacity: making proactive and informed choices about alternative livelihood strategies based on an understanding of changing conditions.

Transformative capacity: the governance mechanisms, policies/regulations, infrastructure, community networks, and formal and informal social protection mechanisms that constitute the enabling environment for systemic change.

[4] Important in understanding how these markets function bipolar economy is an internal rotating market system (the open-air markets found throughout the country) that serves as a redistribution mechanism for domestic produce as well as imported staples. Imported goods reach the markets through second-tier distributors that service the formal network from urban markets to rural ones. The local foods move in the opposite direction, from rural countryside, to village markets, to regional market, to urban market. Typically, local produce is taken to market by a member of the household and/or sold to an itinerant intermediary (Madan Sara), who then travels to a rural or urban market, or sells directly to a market vendor or other reseller, who then sells to the consumer. Markets in provincial towns and the countryside are held on different days. As one moves up the chain from very rural to town to city, market days tend to increase from once to twice or more weekly, to the point where they typically open every day in urban areas.

[5] The internal rotating market is an ancient system with roots in subsistence gardens of colonial era slave system but that in the wake of independence evolved into a burgeoning market system that for most of the past 200 years has been the backbone of the Haitian economy and household livelihood strategies.

[6] The system is such that women may sell daily small quantities of items produced by the household- such as eggs, manioc or pigeon peas. But the prevailing strategy is for one women to specialize in a particular item, such as limes, buy small quantities from multiple farms, accumulate a profitable quantity, and then take them to market or sell them to another intermediary higher up the chain, one more heavily capitalized, who accumulates greater quantities and who is likely destined for a larger town market, city or, the holy grail, Port-au-Prince.

[7] The market system is emphatically not oriented towards “wants,” but rather subsistence and local production. The overwhelming bulk of products sold are inexpensive, locally produced and somehow related to production and subsistence; with respect to the profits that the machann earns, the bulk of the money is destined for reinvestment in commerce, other income generating enterprises – such as fish traps – or spent on subsistence foods and necessities for the household and, ultimately, the growing ‘mama lajan‘ (literally “mother money,” or more technically, the principal or capital) preserved for economic recuperation during times of crisis.

[8] New York Times Jan. 10, 2022 Haitian Prime Minister Had Close Links with Murder Suspect. By Anatoly Kurmanaev.

[9] The political situation looked like it might improve in 1990 when the immensely popular, leftist Lavalas movement propelled Jean Bertrand Aristide to power. A historic 70 percent of the eligible population voted, 67 percent of them for Aristide. Six months later, a group of CIA trained military army officers, sympathetic to the merchant toppled the regime. Three years of a violently repressive military junta and an international trade embargo followed. A US invasion restored Aristide to power in 1994 and the embargo was lifted. By that time the formal economy was all but non-existent. The number of Haitians employed in factories had fallen from 30,000 to 400 workers. At the same time, the Haitian merchant elite and a substrata of upwardly mobile nouveau-rich had become smugglers and money launders par excellence, an industry they proceeded to perfect as middlemen in the flow of cocaine from Colombia to the US. Coupled with the highest levels of the merchant elite that controls imports and exports, Haiti’s new role in transshipment of recreational drugs was to become the major political destabilizing factor.

From 1995 to 2000 a UN military peacekeeping force was deployed in Haiti. Notwithstanding, the capital city of Port-au-Prince began a descent into lawlessness. Banditry and kidnapped increased. Aristide was elected president again in 2000 with another historic~70 percent voter turnout, this time winning 90 percent of those votes. The UN left the same year (2000) and the situation deteriorated even further. Territorial gangs were armed on the one hand by narcos, right-wing politicians and businessmen seeking to destabilize the government and on the other hand by the left-leaning government and its partisans seeking to maintain power. Weakened by the suspension of foreign assistance to the Haitian Government and aggressive opposition from the small upper middle class and elite, in 2004 a small cadre of 200 US supported soldiers toppled the government and Aristide was flown into exile.

The next two years saw a near total break down in Haitian civil society. The gangs and some of the military insurgents that had been used as political proxies in the fight for control of the country now became freelance kidnappers and armed bandits. They fought one another to monopolize urban produce markets where some 80 percent of the population bought and sold the food they need to survive. A new UN peacekeeping force deployed in 2004 did little to calm the situation.

With the election of Rene Preval in 2006, the violence began to subside. Preval negotiated truces with gang leaders. The UN peacekeepers and the Haitian National Police began to assert themselves, entering popular neighborhoods and engaging the gangs, arresting and even killing some gang members, such as when, in the dead of night, Peruvian forces through a hand grenade into the home of Cite Soley gang leader Dred Wilm (see Kail 2019). More conservative tactics involved a UN disarmament program to reduce the weapons the gangs had. USAID, World Bank, and IDB launched development projects to relieve economic tension in popular neighborhoods. The efforts pacified the worst of the gang excesses. In 2009, with political stability finally seeming to be a reality, the international community, Haitian business community in the country and in the diaspora seeming to be a reality, prepared for a massive investment strategy. Under the leadership of UN Special Envoy Bill Clinton and US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, a cabal of private investors was assembled and preparations began for a massive investment in industry, tourism, and agriculture. The future finally seemed to be brightening for Haiti.

Then, on January 12th 2010, just as the US State Department, the UN Office of the Special Envoy and the Haitian government were finalizing the new investment plan, a devastating earthquake rocked the capital city of Port-au-Prince. Seven percent of all buildings collapsed immediately, 20 percent were damaged beyond repair, and somewhere between 50,000 and 316,000 people were killed. The ensuing 4 years was characterized by massive humanitarian aid and squalid camps in which, at their height, the UN claimed over half the metropolitan population had sought shelter.

In spite of fallout from the earthquake, 2010 to 2015 was the calmest and most prosperous period in nearly a half century. Lending nations and banks forgave the Haitian national debt. Private donors gave NGOs some 4 billion in aid and foreign governments pledged more than $10 billion in aid But by 2016 the money was gone and the country was slipping back into political instability and lawlessness. Massive protests shut the country down for months at a time. Gangs once again took control of popular neighborhoods. By 2020, kidnapping, home invasions and highway robberies were worse than they had been in 2004-2006.

[10] In 2020, Transparency International ranked Haiti the 9th most corrupt country in the world.

[11] Remittances from Haitians who have fled the country more than quadrupled over this period reaching 37 percent of GDP ($3.3 billion in 2019), making remittances the second highest proportion of any GDP in the world (Lindor 2019). Haiti is recognized as the among the top money laundering and drug narco transshipment countries in world, industries that began in mid 1980s and took off during the 1990s (for remittances see, Sabatini 2018:8, World Bank; for money laundering see INCSR 2019).

[12] 2.8 million of Haiti’s 11.5 million inhabitants live in Port-au-Prince.

[13] Leimenstoll, Will. 2014. Planet of the Primate (Cities), In The Urbanist Dispatch. July 10, 2014 https://www.urbanistdispatch.com/2393/planet-of-the-primate-cities/

[14] As with so many issues in Haiti cumulative data is scarce, but to give an example from the authors own research in one of Haiti’s 10 departments, the Northwest: in 1998 and early 1999, while the Haitian State ministries of Health, Educational, Justice and Agriculture Departments were employing 261 people and owned seven motorcycles and three jeeps–four of the motorcycles and two of the jeeps being gifts from NGOs–three NGOs in the same area employed over 800 fulltime workers, and had a combined 94 four-wheel drive vehicles, 192 motorcycles, 28 large transport trucks, two dump trucks and a backhoe. While the State had built some 100 meters of drainage ditch during this time, the three NGOs had employed 21,137 local people each for a period of ten days, while renovating 206.5 kilometers of roads, building over 3,000 meters of irrigation canals, installing over 3,800 cubic meters of anti-erosion walls, and capped 67 water sources (see Schwartz 2000).

WORKS CITED

Arcos, Eduardo. 2021. “Data Illustrates Magnitude of Haiti’s Kidnap-For-Ransom Crisis.” In Forbes. June 16, 2021.

Caitlyn Yates. 2021. Haitian Migration through the Americas: A Decade in the Making. Migration Policy Institute (MPI). September 30, 2021

https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/haitian-migration-through-americas

Cénata , Jude Mary, and Daniel Derivoisb, Martine Héberta, Laetitia Mélissande Amédéea,Amira Karray. 2018. Multiple traumas and resilience among street children in Haiti:Psychopathology of survival. Child Abuse & Neglect 79 (2018) 85–97

Charlot, Jeudy 2019. Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on September 12, 2013.

CIA 2020. World Fact Book.

Divinski, Randy, Rachel Hecksher, and Jonathan Woodbridge, eds. 1998. Haitian women: Life on the front lines. London: PBI (Peace Brigades International). At www.peacebrigades.org/bulletin.html.

EMMUS-I. 1994/1995. Enquete Mortalite, Morbidite et Utilisation des Services (EMMUS-I). eds. Michel Cayemittes, Antonio Rival, Bernard Barrere, Gerald Lerebours, Michaele Amedee Gedeon. Haiti, Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-II. 2000. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Florence Placide, Bernard Barrère, Soumaila Mariko, Blaise Sévère. Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-III. 2005/2006. Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD : Macro International.

EMMUS-VI. 2016-2017. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services. Indicateurs Clés. Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population (MSPP) Institut Haïtien de l’Enfance (IHE) Pétion-Ville, Haïti The DHS Program ICF Rockville, Maryland, USA Septembre 2017

Francis, Donette A. 2004 Silences too horrific to disturb: Writing sexual histories in Edwidge Danticat’s Breath, eyes, memory. Research in African Literatures 35(2):75–90.

Fuller, Anne. 1999. “Challenging Violence: Haitian Women Unite Women’s Rights and Human Rights.” Association of Concerned Africa Scholars. Spring/Summer. Special Bulletin on Women and War. ACAS website: http://acas.prairienet.org

Fuller, Anne. 2005. Challenging violence: Haitian women unite women’s rights and human rights special bulletin on women and war. At acas.prairienet.org. accessed October 19, 2006. Originally published in the Spring/Summer 1999 by the Association of Concerned Africa Scholars.

Haitian Migration through the Americas: A Decade in the Making – SEPTEMBER 30, 2021 – Migration Policy Institute

Heinl, Roberts Debs and Nancy Gordon Heinl. 1996 Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People 1492-1995 newly revised edition

HLCS 2001. Les conditions de vie en Haïti 2001. Person questionnaire (RSI). Haiti Living Conditions Survey (HLCS). Author. IHSI, FAFO, PNUD

Human Rights Watch, 2022, URL: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/haiti 4 Avril 2016 • Par L’AFP pour Handicap.fr

IACHR 2016. Right in Exile Programme, Haiti LGBTI Resources, 2016.

ICE 2021. Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse documents. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

IGLHRC (International gay and lesbian human rights commission) 2011. The Impact of the Earthquake, and Relief and Recovery Programs on Haitian LGBTI People, 2011; ILGA, Homophobie d’Etat, 05/2013, 111p.

IMF 2020 Haiti Selected Issues. IMF Country Report No 20/122. Washington D.C.

INCSR 2019a. United States Department of State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. Volume I Drug and Chemical Control March 2017

IOM 2022. IOM Response to Internally Displaced Persons in Haiti (10 August 2022). Relief Web. https://reliefweb.int/report/haiti/iom-response-internally-displaced-persons-haiti-10-august-2022

James, Erica. 2010. “Democratic Insecurities: Violence, Trauma, and Intervention in Haiti.” California Series in Public Anthropology, p. 267.

Jean-Price Mars, the Haitian Elite and the American Occupation,1915-35By Magdaline W. Shannon 1997

Joseph, Jean Ronald. 2018. Professor at Quisqueya University in Port-au-Prince. June 2018 on Les Représentations sociales et la méconnaissance des LGBT+ en Haïti

Joseph, Jean Ronald. 2018. Professor at Quisqueya University in Port-au-Prince. June 2018 on Les Représentations sociales et la méconnaissance des LGBT+ en Haïti

Kail, Max. 2019. Zombie Files: Gangs, Drugs, Politics and Voodoo under the Mandate of the United Nations

Leyburn, James G. 1966 (originally 1941) The Haitian People. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lindor, Moise. 2019. Government, poverty and corruption in Haiti. Critical reflections on two social programs, brain drain and destination countries. Research Gate. (PDF) Government, poverty and corruption in Haiti. Critical reflections on two social programs, brain drain and destination countries (researchgate.net)

Moncrieffe, Joy. 2007. When label stigmatize: encounters with ‘street children’ and ‘restavecs’. Institute for Applied Social Research. Researchgate.

New York Times Jan. 10, 2022 Haitian Prime Minister Had Close Links with Murder Suspect. By Anatoly Kurmanaev.

Nieto, David 2020. In Haiti, evangelism hinders LGBT+ rights, Slate.fr

Olsen-Medina, Kira and Jeanne Batalova. 2018. Haitian Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute (MPI). https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/haitian-immigrants-united-states-2018

Pasquali, Marina 2020 Monetary policy rate in selected countries in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1060335/latin-america-country-monetary-policy-rate/ Sep 15,

Prachi, Mishra 2007. “Emigration and Brain Drain: Evidence from the Caribbean,”The B.E.Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy: Vol. 7: Iss. 1 (Topics), Article 24.Available at: http://www.bepress.com/bejeap/vol7/iss1/art24 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/4908483_Emigration_and_Brain_Drain_Evidence_From_the_Caribbean.

Prou, Marc 2009. Attempts at Reforming Haiti’s Education System: The Challenges of Mending the Tapestry, 1979-2004 Journal of Haitian Studies Vol. 15, No. 1/2, Haitian Studies Association 20th Anniversary Issue (Spring/Fall 2009), pp. 29-69 (41 pages)

Rotberg, Robert 1971. Haiti: the Politics of Squalor. Houghton Mifflin; 1st edition

Sabatini, Christopher 2018. The Caribbean Basin 2030: Political, Economic and Security Outlook. FIU. Funded by the US Southern Command. Stephen J. Green School of International Public Affairs.

Schiff M. and O Caglar,2005. International Migration, Remittances and the Brain Drain. Palgrave and Macmillan, Ltd, Hampshire.

Schwartz, Timothy 2017. The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle. Create Space.

Schwartz, Timothy 2019. Impact of Migration on Haitian Social System and Bureaucracy. https://timothyschwartzhaiti.com/impact-of-migration-on-haitian-social-system-and-bureaucracy/

Schwartz, Timothy 2019a. The Haitian Boutik (‘neighborhood convenience store’). https://timothyschwartzhaiti.com/tag/haitian-boutique/

Schwartz, Timothy. 2019b. Haiti Hope Gender Travesty, https://timothyschwartzhaiti.com/haiti-hope-gender-travesty/

Schwartz, Timothy. 2019c. History of Beneficiary Selection and Targeting in Haiti. https://timothyschwartzhaiti.com/impact-of-migration-on-haitian-social-system-and-bureaucracy/

Schwartz, Timothy. 2019d. Ngo Interventions, Associations and the Market Chain: Risk of Putting Women Out of Business, https://timothyschwartzhaiti.com/gender-and-fish-value-chain-in-haiti/

Schwartz. Timothy 2019e. History of CARE International and USAID Development Efforts in Far West Haiti. https://timothyschwartzhaiti.com/care-international-haiti/

SEROvie. 2010. The Impact of the Earthquake, and Relief and Recovery Programs on Haitian LGBT People, 2010 DIDR – OFPRA 17/04/2020

Shannon. Magdaline W. 1997. Jean-Price Mars, the Haitian Elite and the American Occupation, 1915-35. Palgrave Macmillan UK

Statista 2021 https://www.statista.com/statistics/983225/income-distribution-gini-coefficient-haiti/#:~:text=A%20value%20of%200%20represents,from%2060.8%20as%20of%202015

The Urbanist Dispatch. July 10, 2014https://www.urbanistdispatch.com/2393/planet-of-the-primate-cities/

Transparency International 2020

UNIFEM (United Nations Development Fund for Women) 2004, July, “UNIFEM in Haiti: Supporting Gender Justice, Development and Peace. United nations Development Fund for Women (July, 2004). Gender-related trends in Haiti.

University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts (CLA) 2018. Postcolonial Homophobia: How religious constructs affect the LGBTQ community in Haiti, 2018.

USAID 2017.Enumerator Guidance: Full Model. A GUIDE FOR IMPLEMENTING A RESILIENCE MODULE, p. 2. at for most of the past 200 years has been the backbone of the Haitian economy and household livelihood strategies.

Valbrun, Marjorie. 2012. After the Quake, Praise Becomes Resentment In Haiti. The Center for Public Integrity. January 10, 2012

Vatav, M. 2012 (August 20). Turing the brain drain into the brain gain. Haiti Business Week . http://www.haitibusinessweek.com/articles/19/turning-the-brain-drain-into-the-brain-gain

Verner, Dorte 2008. Making poor Haitians count–poverty in rural and urban Haiti based on the first household survey for Haiti. International Bank for Reconstruction & Development (IBRD), World Bank Group, (more information at EDIRC)

Voltaire, Louis Justin. 2015. Les conséquences et les effets de l’étiquette de « déportés » sur les vécus des immigrés haïtiens expulsés par les États-Unis d’Amérique. Mémoire de maîtrise, Montréal, Université de Montréal, École de service social.

Weinstein, Brian, and Aaron Segal. 1984. Haiti: Political Failures, Cultural Successes. Stanford,

World Bank 2002. A review of gender issues in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica. Report No. 21866-LAC. December 11th , Caribbean Management Unit, Latin America and the Caribbean Region.

World Bank 2012. How Close Is Your Government to Its People? Worldwide Indicators on Localization and Decentralization. Policy Research Working Paper 6138. The World Bank East Asia and the Pacific Region Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit March 2012

World Bank 2015. Haiti: Towards a New Narrative Systematic Country Diagnostic. May 2015. Latin America and the Caribbean Region

World Bank 2020 https://www.worldbank.org/en/home

World Bank Prospects Group. 2020. Annual Remittances Data, April 2020 update.

World Bank, 2021, URL: https://www.banquemondiale.org/fr/news/feature/2021/12/17/greater-inclusion-necessary-for-haitians-living-with-a-disability

World Population Review. 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/haiti-population