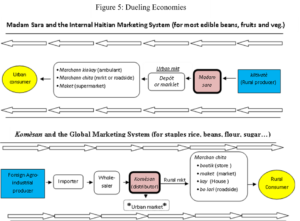

There are two principal market channels in Haiti by which food reaches consumers: the informal internal rotating marketing system that evolved dealing principally in local produce, and the formal import economy that evolved in association with imported goods. These two principal market distribution channels supply a third channel, the increasingly important food preparation specialists. Anyone interested in the growth of food preparation specialists in Haiti can read this post about Street Food in Haiti. In the present article I briefly describe the principal two channels, how they function today, the principal actors in each and how they relate to one another. To support my major points, I use data from research I’ve conducted in the past and I provide graphic models that illustrate flows of goods through the Haitian market channels (another relevant post is History of the Internal Rotating Market System).

The Haitian Market System

Internal Rotating Market System

Until the first decade of the 2000s, most Haitians lived on small farms. But Haitians are not and probably never were subsistence farmers. The overwhelming evidence is that since the days of the colonial plantation system they have been heavily oriented towards the market, specifically what anthropologists call the internal rotating market system (see Schwartz 2009; Murray 1972, Mintz 1974).

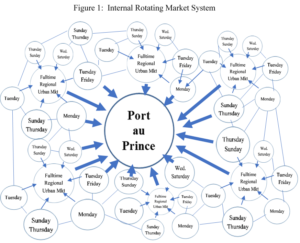

Mountain micro-climates with differing rain patterns result in staggered harvest seasons. This has allowed for the evolution of intense interregional trade. Buying and selling is dominated almost entirely by women–revande (stationary resellers) and madan sara (itinerant traders). Household producers sell to itinerant traders who move produce to local or larger regional markets. There, resellers market goods to local consumers or to other madan sara who move the goods up the line to full-time markets in urban areas, and ultimately to the holy grail of all markets, Port-au-Prince, which is now home to 1/3rd of the Haitian population. The market system is highly competitive and efficient, especially given the rough terrain and horrendous road conditions. The same is not true of traditional exports, which moved through parallel but monopsonistic channels controlled by elite-owned export houses allied with the state.[i]

The internal rotating market system consists of rural open-air markets. These markets occur on alternating days of the week, staggering the operations among towns in any given region. This gives most people throughout Haiti access to markets within walking distance at least two days per week. [ii]

For the poor who participate in these markets—including rural households selling produce, and urban-based women purchasing items for resale—the system serves as a medium of storage. The stored household surplus can first be sold and, second, prolonged and even expanded by rolling over the cash in the market to produce petty profits. When periods of scarcity strike, the family begins to consume this money, and dip into other forms of household savings by selling off livestock or making charcoal. From the perspective of consumers, it is this system that has allowed the urban lower, middle, and elite classes to survive the frequent disasters, embargoes, and civil insurrections that have plagued Haiti in the 200 years since independence.[iii] [iv]

Formal Import Market System

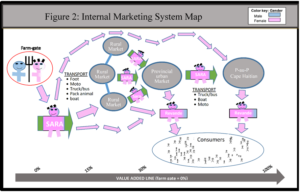

The internal rotating market system is juxtaposed against a formal system that deals almost entirely with imported goods. This system has only become important, with regard to processed foodstuffs, as a function of the urbanization of the past 50 years. At the highest level are major distributors who import mass quantities of processed foods—cookies, crackers, cheese puffs, cheese spreads, sugared beverages, as well as staples such as rice and cooking oil. Sometimes these distributors repackage products with their own logos, branding, and culturally appropriate marketing imagery that appeals to the interests of Haitian consumers. The next level of the system is bifurcated (see Figure 4). One path leads to modern urban, air-conditioned supermarkets offering a plethora of brands from the US and Europe that compete with repackaged and locally labeled goods sold to wealthy and upper-middle-class consumers (roughly 10% or less of the population, overwhelmingly concentrated in Port-au-Prince). The other path leads to smaller distributors in major cities, provincial towns, and rural areas. These wholesale outlets, or depo, supply small shops or boutik, and individual merchants who sell directly to consumers on the street or in open-air markets (although many depo also sell retail).

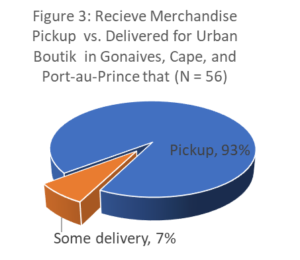

The formal market channel in Haiti has one key characteristic that makes it distinct from formal market systems in developed countries or even in other developing countries such as the neighboring Dominican Republic and that is that there is an almost total absence of provider distribution networks. The burden of restocking rests almost entirely with redistributors and retailers, meaning that the vast majority of depo and boutik owners must retrieve their merchandise themselves from bigger depot closer to ports of entry in cities. This is true for both rural and urban areas (see Figure 3). There are a few exceptions, such as snack-maker Stanco, which in 2013 had its own distribution network of some 15 trucks and could effectively leverage that network to get products onto the local market. But the role of these delivery trucks is minuscule compared to the gross movement of goods. The norm is for people to go and purchase their own stock.

One point to bear in mind regarding the distinction between this formal market chain and the local internal marking system is that while on the internal system there are what might be considered non-subsistence goods—such as hair products and some cosmetic and even pharmaceuticals—each of these value chains has its own distinct system and they represent a small portion of what is found in the informal market system. The majority of products emphatically have to do with subsistence rather than wants. You will not even find toilet paper on the informal system and even industrial snack foods are usually linked to a formal market system vendor.

Mechanics of the Haitian Formal and Informal Market Systems

The two market distribution channels described above run in opposite directions: the internal rotating market system is part of an informal economy through which local produce moves from rural farm to village, town, and city. In contrast, the formal system is the means by which imports enter the country and then move to urban neighborhoods, and then to towns, villages and rural areas.

Goods from both chains enter into the popular channels of the other: imported goods are sold in the open markets and to a lesser extent local produce is sold in boutik and supermarkets. But the principal intermediaries in these two contrary market channels are almost exclusively involved only in their own chain: for the informal internal market system it is the madan sara, for the formal system the principal mover is called a komesan.

A madan sara is an itinerant market woman and the country’s primary accumulator, transporter, and redistributor of agricultural produce, small animals, crafts, and fish. The poorest madan sara work with as little as US$2.00 in capital and walk to and from regional market centers. The average sara has US$50 in capital and may own a pack animal that she loads with local produce and hauls to a regional market or provincial city. The most heavily capitalized sara deal with thousands of US dollars’ worth of local produce, and may own or lease a truck to haul tons of produce. If she travels to Port-au-Prince, the sara typically stores her goods in warehouses open to the public and frequented by other sara. She sells her produce in a matter of days. More than half of the time (~64%) she provides goods on credit to revande, or retailers, or other sara who detail in low level, wholesale redistribution. Depending on the distance traveled, her profits vary from 30% to 100% (estimates are based on Stam 2013 and Schwartz 2009).

The most significant marketing agent in the formal economy is the komèsan (distributor). As or more often a man than a woman, the komèsan is the handler of durable staples imported from overseas. He or she moves in the opposite direction from the sara, from urban to province city, town, village, rural market place or boutik. The komèsan is heavily capitalized (from hundreds of thousands of US dollars at the highest levels in Port-au-Prince, to hundreds of US dollars at the most remote rural depots). She/he often has access to a line of credit and always moves his or her sacks of rice, flour, sugar, and beans, and cases of edible oil, crackers, and cookies by truck. She/he owns or leases a warehouse, store or storage facilities. Komèsan profit margins are as low as 5% and seldom exceed 20 percent. Turnover rates can exceed one month.

Both the madan sara and the komèsan make use of the machann, stationary resellers who sit in markets, by the roadside or who walk and peddle goods in streets and neighborhoods (vendors of prepared food fall into this category).

Credit and the Formal Sector Advantage

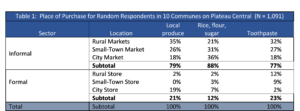

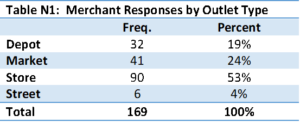

In terms of purchase points for consumers, the informal market sector is the principal distribution channel throughout Haiti. Illustrative of the point is that on the Plateau Central in 2013, we found that consumers even purchase toothpaste primarily in the open, rotating and roadside markets. [v]

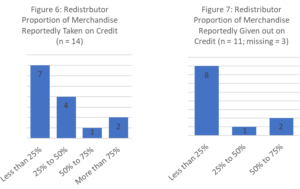

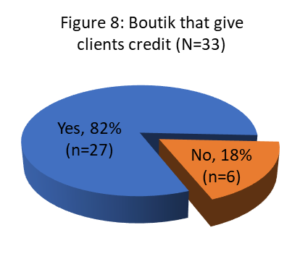

However, while the informal economy prevails, the incursion of imported items into the informal market gets a significant boost from differential access to credit. In the formal market economy, one sees subsidies and credit operant at every level. Three of five of the distributors interviewed reported receiving more than 50% of merchandise on credit. Every one of the 14 redistributors interviewed receives credit from distributors and gives credit to clients (Figures 6 and 7); 82% of boutik owners interviewed give credit to clients (Figure 8).

The informal sector traditional economy also has mechanisms of credit. Farmers provide produce on credit to madan sara (itinerant traders) who in turn provide short-term credit to resellers at the urban distribution point. But the credit tends to be for small quantities and is short-lived—measured in days. Moreover, the cost of credit in the informal sector exceeds 20% per month. Even if credit is obtained from NGOs or credit unions the cost is typically 3% to 6% per month. In the formal sector, the credit is abundant and free.

What the differential access to and cost of credit means in terms of advantage is that formal sector entrepreneurs do relatively big business with no capital and they pay nothing; entrepreneurs in the informal sector tend to do petty business, and they must either have their own money or pay exorbitant fees to borrow. The situation is such that at any given time 8% of informal sector entrepreneurs are operating with funds that they got from taking formal sector merchandise on credit and then selling at below-market costs, creating the ironic spectacle of impoverished informal sector actors using profits earned from redistributing local produce to subsidize the wealthier formal import sector (see this post).

WORKS CITED

Mintz, Sidney 1974. Caribbean transformations. Chicago: Aldine.

Murray Gerald F. 1972. The economic context of fertility patterns in a rural Haitian community. Report submitted to the International Institute for the Study of Human Reproduction. New York: Columbia University.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2009 Fewer Men, More Babies: Sex, family and fertility in Haiti. Lexington Press. USA

Stam, Talitha 2012, From Gardens to Markets Rural women on the move to urban markets, Route Seguin Haiti A Madan Sara Perspective Commissioned by CORDAID for the IS ACADEMY Human Security in Fragile States

NOTES

[i] Important in understanding how these markets function bipolar economy is an internal rotating market system (the open-air markets found throughout the country) that serves as a redistribution mechanism for domestic produce as well as imported staples. As described above, the imported goods reach the markets through the same second-tier distributors that service the formal network from urban markets to rural ones. The local foods move in the opposite direction, from rural countryside, to village markets, to regional market, to urban market. Typically, local produce is taken to market by a member of the household and/or sold to an itinerant intermediary (Madan Sara), who then travels to a rural or urban market, or sells directly to a market vendor or other reseller, who then sells to the consumer. Markets in provincial towns and the countryside are held on different days. As one moves up the chain from very rural to town to city, market days tend to increase from once to twice or more weekly, to the point where they typically open every day in urban areas.

[ii] The internal rotating market is an ancient system with roots in subsistence gardens of colonial era slave system but that in the wake of independence evolved into a burgeoning market system that for most of the past 200 years has been the backbone of the Haitian economy and household livelihood strategies.

[iii] The system is such that women may sell daily small quantities of items produced by the household- such as eggs, manioc or pigeon peas. But the prevailing strategy is for one woman to specialize in a particular item, such as limes, buy small quantities from multiple farms, accumulate a profitable quantity, and then take them to market or sell them to another intermediary higher up the chain, one more heavily capitalized, who accumulates greater quantities and who is likely destined for a larger town market, city or, the holy grail, Port-au-Prince.

[iv] The market system is emphatically not oriented towards “wants,” but rather subsistence and local production. The overwhelming bulk of products sold are inexpensive, locally produced and somehow related to production and subsistence; with respect to the profits that the machann earns, the bulk of the money is destined for reinvestment in commerce, other income generating enterprises – such as fish traps – or spent on subsistence foods and necessities for the household and, ultimately, the growing ‘mama lajan‘ (literally “mother money,” or more technically, the principal or capital) preserved for economic recuperation during times of crisis.

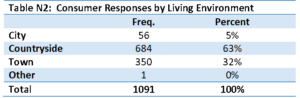

[v] Origins of consumers in the 1,091 respondent survey from 10 Communes in the Plateau Central