This article describes and attempts to explain the recent growth in Haiti’s street food cottage industries. Underlying the growth in street foods is urbanization and challenges that come with it. The challenges can be summed up as, “The Food Preparation Conundrum,” which can be further broken down into problems that the the street food industry helps resolve,

1) The Storage problem: Rodents, molds, thieves, and scarce cash make storage risky and costly.

2) The Water Problem: Most people in Haiti, even in rural areas, must either purchase travel to fetch the water they use to cook with.

3) The Fuel Problem: In rural areas people must forage for wood. In the urban areas they use charcoal, which in the prevailing scale of economies, becomes relatively less expensive as the amount of food being cooked increases.

4) The Labor Problem: Someone has to take the time to cook the food, and with the increasing importance of school and work outside the home, there are less household members available to participate in food preparation.

The street food vendors help solve these problems and they do so at a lower cost than households can prepare food. In this way street foods function as a type of collective mechanism to obviate the need for storage, pool the costs of fuel and water, and overcome the scarcity of domestic labor. The history and emergence of the industry is explored in greater detail below.

Food Preparation Specialists

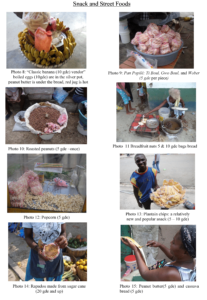

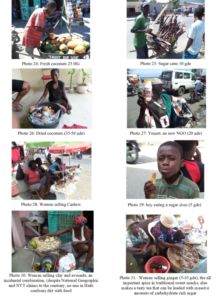

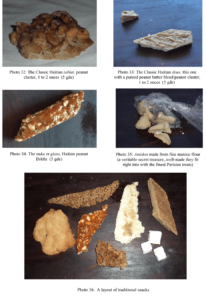

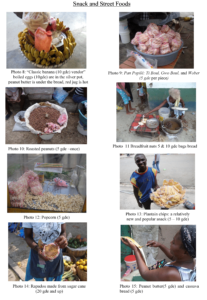

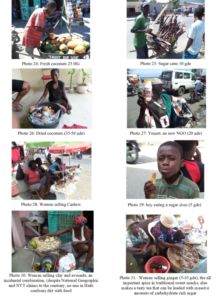

Food preparation specialists in Haiti ply their businesses at bus stations, crossroads, and near many major workplaces, such as construction sites and factories. The foods they prepare and sell vary by time of day. In the morning, preparation specialists have traditionally sold coffee, hot chocolate, porridges, bread, peanut butter, boiled eggs, and patey. At mid-day, small makeshift restaurants known as chen jambe (dog crossing) serve lunch, typically heavy in carbohydrates of rice and/or plantains or tubers, and rich in protein from beans, chicken or another meat based sauce. At night in any hamlet, village or town the streets are and long have been lined with flickering gas lamps of vendors peddling tablet (peanut sugar clusters), varieties of fried doughs, starchy vegetables, and a fried fish, chicken, goat, and pork (see here for a more detailed exploration of Haitian meals).

The Rise of Street Foods

With urbanization, towns, villages, and especially cities in Haiti have experienced an explosion in street foods. As early as 1983, a study of 174 Port-au-Prince secondary school students found they obtained 25% of their calories and 16% of their protein from street foods (Webb and Hyatt 1988). Eating street food has cost advantages. The 100 HG (25% the cost of the meal) that goes to buy fuel to feed a family of six, can now be used to cook for 30 people. Contrary to developed countries where the rule of thumb for fast food and restaurant markups on food is 300%, in Haiti the economy of scale and intense competition among the thousands of restaurants and street vendors drive down the markup down to less than 50% and, if the economy of scale on fuel and water costs is considered, make it equal to or lower than the cost to make a similar meal at home (see Table 1).

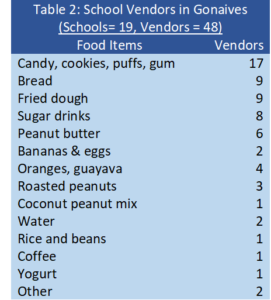

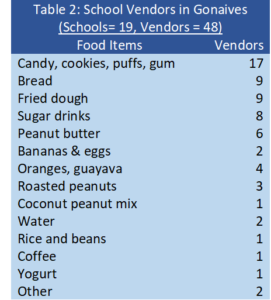

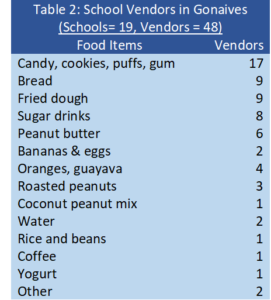

To give an idea of the extent of the industry and items sold in Tables 2 and Table 3 is a list of vendors that we counted at intersections in Cape Haitian and in front of schools in Gonaives, and the foods they were selling. [i]

Understanding the Rise of Street Foods: The Food Preparation Conundrum

Whether a household prepares a meal or its members seek food elsewhere is not, as food security specialists working in Haiti so often assume, simply a function of food availability. It is equally or more importantly a function of time and cost involved in going out to get the food, water and fuel necessary to make a meal, and the labor to actually cook it. We can conceptualize the challenge as popular class Haiti’s “food preparation conundrum,” composed of essentially four sub-problems that almost all Haitians face regarding preparation of meals. These four problems are: the storage problem, the water problem, the fuel problem, and the labor problem.

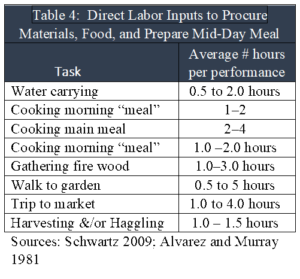

The Storage Problem: Because of rampant infestations of rats, insects, rot, and mold in a subtropical environment, rural and urban dwelling Haitians alike typically do not keep more than 2 to 3 days of food on hand. This means that to make most household meals someone has to go out and get the food. If the food is from a garden—which with fresh produce is often the case even in the city–that person has to go to the garden, an average round trip distance in rural areas of about 92 minutes. Selective harvesting takes another one to two hours. If they do not get the food from the garden, they most often get fresh produce from the market or, in the case of rice, beans and other imported staples boutik (store), and to a lesser extent, the households of women who specialize in selling specific commodities. In rural areas, going to the market involves an average round-trip walking time of three hours (twelve kilometers). Even in urban areas, at least 1 hour must be dedicated to getting to the market, locating what is desired, then haggling over the price and getting back to the household.

The Water Problem: Water is necessary for cooking and washing pots and dishes. But in all of Haiti, only 9.2% of households have an on-premises source of water; 34% must send someone more than 30 minutes away to retrieve water (EMMUS 2012). For those in rural areas the figures are more extreme: only 4.8% of rural homesteads have water on the premises (heavily skewed by specific regions, such as the irrigated Artibonite); 42.6% must travel more than 30 minutes to retrieve water (ibid). Even if the water is close to the house, actually getting it often means contending with pushing and cursing crowds of women and children, meaning it can take anywhere from a few minutes to hours to get a turn at filling a water bucket.

The Fuel Problem: Perhaps the other major non-nutritional limiting factor regarding meals is fuel. In all of Haiti only 4% of the population uses fuels other than wood or charcoal, specifically propane, kerosene and electricity. The vast majority of those using these other fuels are located in Port-au-Prince, (where still only 13% of the population uses fuel other than wood or charcoal; ibid). Thus, in Haiti it’s basically wood or charcoal. And the distinction between a household that uses wood vs. charcoal to cook is not income so much as rural-urban residence: 80% of those in the city use charcoal, 73% of those in rural areas use wood (ibid).

For the urban majority that must use charcoal to make a meal, the charcoal is the single greatest cost, greater for the for the average family of five than any single item of food in typical mid-day meal. It takes about 75 to 100 HG of charcoal to make a mid-day meal for 5-6 people.[ii] Another 5 HG of pitch pine is typically purchased as tender. Unlike with wood which can be used directly on the ground, the charcoal is compact and must be put into a recho–a type of grill that—so that air circulates beneath it and makes it burn. This means the additional cost of the recho. In the case of firewood, someone has to gather it. Due to deforestation and competition with other households that need wood, too, the task can take 1 to 3 hours.

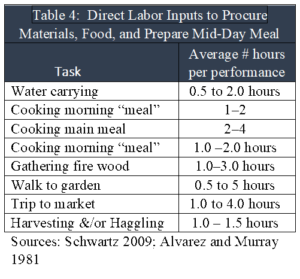

The Labor Problem: Actually cooking any meal takes time and it takes labor, especially the mid-day main meal. With both firewood and charcoal, cooking time depends on the quality of the fuel. If the firewood is dry, seasoned, and of high quality, rice or sweet potatoes can be boiled in about one hour. Beans, if dried, must be boiled for as much two hours. If fresh they take only twenty minutes to prepare, but someone has to take the beans out of their pods. Preparing meat is time consuming as well. Poultry is the main source of meat, and since most people lack access to refrigeration the vast majority of popular class Haitian buy their chickens live. This means someone has to kill, scald and pluck the bird. All other meats are purchased daily. And popular class Haitians use extreme caution with meats. Whether poultry, red meat, or fish, the meat is washed with sour oranges or limes, boiled and then fried or cooked into a sauce, adding an hour to the time it takes to prepare a meal (for additional data on the high labor and time inputs that go into preparing the daily meal see also Alvarez and Murray 1981). Most families can only afford a single recho. They also do not want to waste charcoal—as seen, the single greatest expense–which means that everything is usually cooked on the same burner, making to take longer to cook the meal. [iii]

Summary of the Costs

The enormous demands for preparing a mid-day meal mean that households cannot reasonably be expected to repeat the endeavor multiple times during the day. The cost of the fuel to cook three meal per day would, alone, amount to as much as 300 HG (US $6). Which is according to several recent studies, about 60% of the average 500 HG per household food budgeted per day (Socio-Dig 2012; EarthTech 2014). Nor is it necessary to make multiple elaborate meals per day. Haitians have resolved the problem of high fuel costs through an increasing reliance on preprocessed foods and they average costs of fuel out through the growing industry of street food vendors discussed below.

Sociological Impact of the Food Preparation Conundrum

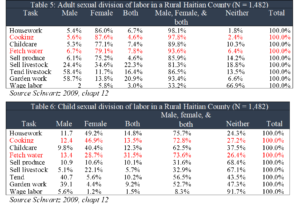

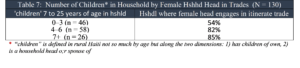

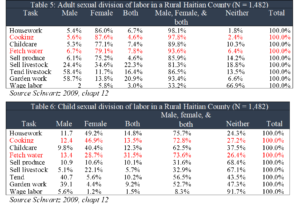

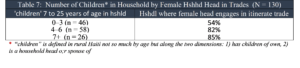

The sociological significance of the food preparation conundrum described above cannot be underrated. There are enormous demands associated with procuring and preparing food and similar to the history of hunger and socialization for scarcity seen here, these demands are among the principal conditioners of traditional Haitian kinship and family patterns. The challenges were traditionally resolved through the pooling of labor in the context of economically autonomous households household in which primary features were a sexual and age division of labor (see Table 5 & 6), heavy dependency on child labor to complete domestic tasks such helping with meals. It was access to and control over the labor of children that underwrote—and still largely underwrites—Godparentage, and even conjugal union. So important are children and their labor that in rural areas there was essentially no such thing as a household without working age children (~ 5 years and up), i.e. it ceased to exist. Moreover, it is the presence of children, in view of the high labor cost of food preparation and domestic activities that assure a steady supply of food, that determined/s whether or not a woman is free to engage in income generating activities outside of the home (see Table 5).

Ramifications of what is being described includes a logic for maintaining extremely high rates of childbirth (until recently among the highest in the world), emphasis on extended kinship relations, female acceptance of—and even pursuit of–polygynous unions with economically independent males (i.e. because they needed economic support to establish a household and rear the children to ages where they could contribute to the labor pool), emphasis on god-parentage (control over child labor in exchange for occasional support), and inter-household cooperative strategies, such as reciprocal meal sharing described by Alvarez and Murray (1981, see also Schwartz 2009 for an extensive investigation of the topic). But now, with the extremely rate of high urbanization described earlier, these traditional strategies are buckling, fuel, labor, and time become scarcer and new solutions are moving into the void.

Ramifications of what is being described includes a logic for maintaining extremely high rates of childbirth (until recently among the highest in the world), emphasis on extended kinship relations, female acceptance of—and even pursuit of–polygynous unions with economically independent males (i.e. because they needed economic support to establish a household and rear the children to ages where they could contribute to the labor pool), emphasis on god-parentage (control over child labor in exchange for occasional support), and inter-household cooperative strategies, such as reciprocal meal sharing described by Alvarez and Murray (1981, see also Schwartz 2009 for an extensive investigation of the topic). But now, with the extremely rate of high urbanization described earlier, these traditional strategies are buckling, fuel, labor, and time become scarcer and new solutions are moving into the void.

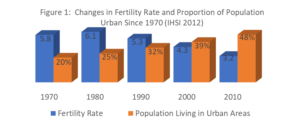

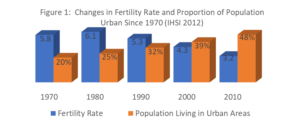

It is in this context that there has been an explosion of the food specialists. Specifically, the shift in dependence from traditional agricultural production to urban-based wage labor means adults are engaged in work away from the homestead and therefore not present to devote time to preparing the traditional mid-day meal; plummeting childbirth rates (see Figure 1) mean fewer children are available to help prepare meals; and, increasing emphasis on education removes those children from the household labor force precisely during hours of the day most critical for preparing food.

Conclusion

It must also be understood that what is happening in Haiti in the face of these demographic changes is, with regard to other countries in the region, unique to Haiti. In other countries, such as the neighboring Dominican Republic, labor saving strategies such as propane gas, piped water, and processed foods have offset the impact of these changes. But in Haiti, because of the extreme poverty, a history of isolation, and elite monopoly on imports fuel, water, and access to processed foods are still “problems.” What this means for the household, particularly the urban-based household, is that it is increasingly difficult to muster the labor necessary to make a meal. Moreover, many household members would not be present to eat it. It is in this context that one can understand the role of Haiti’s many street foods, or what could be called traditional non-recreational snacks.

Photos of Street Foods in Haiti

WORKS CITED

Alvarez and Murray, 1981Alvarez, M.D.Murray, G.F. Socialization for scarcity: Child feeding beliefs and practices in a Haitian village. United States Agency for International Development

EarthTech 2014. Lafiteau Social Impact Assessment on behlf of GB Group

Socio-Dig 2012 Gender Survey CARE HAITI HEALTH SECTOR Life Saving Interventions for Women and Girl in Haiti Conducted in Communes of Leogane and Carrefour, Haiti

EMMUS 2012 Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haïti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti

Schwartz, Timothy. 2009 Fewer Men, More Babies: Sex, family and fertility in Haiti. Lexington Press. USA

Webb RE, Hyatt SA (1988) Haitian street foods and their nutritional contribution to dietary intake. Ecologyof Food and Nutrition21, 199-209.

NOTES

[i] The counts are only meant to be illustrative. Many items, such as processed cheese and condensed milk, were missing because they are often buried in vendor baskets. There is also the issue of timing: the surveys were conducted late in the morning. Had they been conducted earlier we would have expected more vendors of banana, eggs, bread and peanut butter. Also absent were seasonal items such as mangos, which were not in season at the time of the survey. Following the data from the vendor surveys are three pages of photos and food prices to give the reader a sense of actual foods and their costs.

[ii] Either one simply barters for a quantity out of a sack or one can buy it by the mammit: 25HG per mammit. 3 to 4 mammit (~1.5 to 2 gallon jugs) of charcoal to cook a meal for household of 5 to 6 people. At 25 HG per mammit, that 75 HG, or US$1.50

[iii] In the context of socialization for scarcity and the objective of understanding popular class Haitian’s attitudes and practices regarding food some mention must be made about concern and attentiveness to cooking. Although the evidence is circumstantial, the extremity of food preparation techniques, particularly with regard to meats and fish, seem particularly targets to deal with the unhygienic streets, market places and kitchens where the food is processed. For example, meats are washed with lime or sour oranges, boiled, fried and then embedded in a sauce. Spaghetti is boiled and then sautéed… Many street foods are fried…

Another aspect of cooking strategies is that there are times of day when certain cooking strategies prevail. No morning foods are grilled, some are fried but most are boiled. such as coffee, chocolate, porridges, plantains and bananas. Mid-day meal foods are all boiled and sautéed, never fried or grilled. All notable afternoon and evening foods are fried or grilled. All notable bedtime foods are boiled.

Ramifications of what is being described includes a logic for maintaining extremely high rates of childbirth (until recently among the highest in the world), emphasis on extended kinship relations, female acceptance of—and even pursuit of–polygynous unions with economically independent males (i.e. because they needed economic support to establish a household and rear the children to ages where they could contribute to the labor pool), emphasis on god-parentage (control over child labor in exchange for occasional support), and inter-household cooperative strategies, such as reciprocal meal sharing described by Alvarez and Murray (1981, see also Schwartz 2009 for an extensive investigation of the topic). But now, with the extremely rate of high urbanization described earlier, these traditional strategies are buckling, fuel, labor, and time become scarcer and new solutions are moving into the void.

Ramifications of what is being described includes a logic for maintaining extremely high rates of childbirth (until recently among the highest in the world), emphasis on extended kinship relations, female acceptance of—and even pursuit of–polygynous unions with economically independent males (i.e. because they needed economic support to establish a household and rear the children to ages where they could contribute to the labor pool), emphasis on god-parentage (control over child labor in exchange for occasional support), and inter-household cooperative strategies, such as reciprocal meal sharing described by Alvarez and Murray (1981, see also Schwartz 2009 for an extensive investigation of the topic). But now, with the extremely rate of high urbanization described earlier, these traditional strategies are buckling, fuel, labor, and time become scarcer and new solutions are moving into the void.