NGO Interventions, Associations and the Market Chain: Risk of Putting Women out of Business

NGOs have intervened in the purchasing-processing-storage-and-marketing chain to help fishermen get better prices for their fish and thereby bolster income to impoverished households. This support has encouraged the formation of male-dominated fishing associations. In addition to help with offshore fishing, they also often provide the associations with coolers and cold rooms for conserving fish and they help link the associations to urban purchasers. These efforts have only been partially successful, but it should be noted that in doing so, by enabling associations to process, store and market fish, they may have delivered two inimical blows to the impoverished households that depend on fishing:

1) by encouraging the sale of fish directly to urban markets they deprive households of the opportunity to profit at three additional links in the value-added chain: processing, transport, and sales.

2) by helping facilitate the entrance into the market chain of male-dominated associations, they may have unwittingly initiated a process of supplanting women from the fishing market chain; indeed, the oddity of the male achtè in the midst of the almost entirely female-dominated sphere of rural market intermediaries suggests that his role may have evolved from the associations

The details of the market chain and how fishing cooperatives have encouraged encroachment of males on female marketing activities is elaborated below.

Post Harvest Fish Value Chain in Haiti: Purchasing, Processing, Storage, Transport and Market

Purchasers

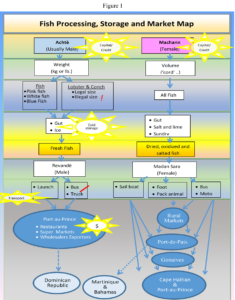

As with infrastructure, fishing materials and fishing strategies (see Formal vs. Artisanal Fishing in Haiti), there are two chains in Haiti: the traditional one and a more modern one linked to the urban, formal economy consumers. The machann (trader), who buys with an eye toward the domestic and popular markets, represents the traditional chain. The achtè (buyer)¸ who buys with an eye toward the high end urban market, represents the modern link.

A machann, almost always a woman, purchases, processes and sells fish. She buys the fish based on volume, not weight. She depends on labor from children, usually girls, and other female family members, to process the fish: specifically, gut, scrub with lime or sour oranges, heavily salt, and then sun-dry the fish on wooden racks. She may sell the cured fish to a sub-category of a machann, the madam sara (pronounced ma-dan sara),[i] or she may herself be a madam sara. A madam sara is an itinerate market woman and the country’s primary accumulator, transporter, and redistributor of agricultural produce, small animals, crafts, and fish. After processing the fish or buying already salted and dried fish, the madam sara transports her product to a local regional market or to fulltime market in one of the principal provincial cities or Port-au-Prince. There she either sells them to local consumers, to another madam sara or machann.

The achtè, almost always a male, is linked to the modern deep sea industrial fishing strategies seen above, those who use long lines and exploits FADs to catch large fish prized in urban restaurants, elite and expatriate households, and the tourist sector. As such he represents a relatively new market chain. The achtè deals only in fresh fish. He buys the fish based on weight not volume. He has an adult woman or child family member – usually a girl – clean the fish. He then preserves the fish on ice. He may sometimes sell the fish to a machann but he is usually linked to urban purchasers and his primary objective is to get the fish to the city on motorized sea vessel or bus or take them himself by boat or bus to the urban market. (Elsewhere in Haiti the achtè shares his position with the “association” which also purchases for the urban mark.

Capital and Credit

A significant and telling characteristic of the entire fishing production and marketing system is that the fishermen carry the burden of capitalizing the rest of the market chain. Rather than urban agencies, the achtè or machann giving credit to fisherman so that they can invest in materials and supply fish to the market, it is the fisherman who gives fish on credit to the machann and achtè. However, the machann is more inclined to lend the fisherman money when he is in need. The machann also more often a wife, or family member of the fisherman or at least a local woman. The loan that she sometimes extends and the fact that she is embedded in the fisherman’s personal family or social network also means that she exercises an influence on him beyond the sale price of fish. When the fisherman does sell to the achtè he often preserves his relationship by sharing part of the proceeds with a machann. This personal relationship adds a level of risk management and social integration that goes beyond that most fishermen have with the achtè. Moreover, because the machann is often family means that the profits from the fish might be less overall, but the fisherman’s household reaps rewards at more than one value added link in the market chain. [ii]

Storage, Transport, and Markets

The achtè faces a significant risk. Without ice or refrigeration uncured fish spoil. Ice, when available at all, must be shipped in. All of this means that preserving fish until the time of transport is a risk. Transport itself adds another layer of uncertainty. Anything can and all too often does happen. A transport boat may have to pull into a remote harbor for fear of foul weather, a bus may get a flat tire or overheat, a road may get washed out or rivers engorged and trucks cannot pass, gas rations may suddenly run out, a buyer may back out of a sale, political unrest and riots may shut down all transport. In the case of any of these events – all realities of life in Haiti – the achtè has only a limited time to find ice and keep his fish from rotting.

Not only must the achtè confront the problem of transport, but the market itself depends largely on the Port-a-Prince economy. Tourism in Haiti is all but non-existent. Restaurant and hotels depend largely on a clientele of visiting diaspora, NGO workers, and diplomats. Any one of the frequent political crises that plague the capital can bring business to a grinding halt. The holder of fresh or even frozen fish cannot easily turn to overseas markets. As seen, US and Europe have both banned the importation of seafood from Haiti. Getting the fish into the Dominican Republic means dealing with rent-seeking border agents and then accessing equally fickle and opportunistic middle men,. On top of all of this, the Dominican hotels and restaurants have a domestic fishing industry more developed than Haiti’s and they have readier access to purchasing from overseas suppliers.

The fact that the machann or madam sara has cured her fish means that she is not in a hurry. She can accumulate fish before going to market. The dried fish are also more easily transported. She puts them in sacks, place basins or woven baskets. She then transports the fish to market carrying them on her head, on pack animal, by bus, boat or truck; whatever means assures her the greatest profits.

The machann sells her fish on Haiti’s internal rotating market system. In villages throughout Haiti, open air markets are held on specific days of the week. In any given region the days alternate between nearby market villages such that people living in a particular area are within walking distance of at least two markets per week. The evolution of these markets is organic in the sense that they have not been planned; rather it is the system that has evolved over at least two centuries of intensive intra- and inter-regional trade. The markets are associated with a vibrant female dominated commercial sector. This means to the madam sara who sells fish is that she has a highly stable outlet for her products, one that is accessible through her own efforts, i.e. if she can, and often does, heft her merchandise onto her head and walk.

The map below the two market chains.

NOTES

[i] The term madan sara derives from a highly gregarious, little yellow and black bird introduced to Haiti from Sub-Saharan Africa. Known in English as a Village Weaver (Ploceus cucullatus), the female seems to be constantly collecting food and twigs and carrying them back to her nest, usually in a tree full of hundreds of other nesting madan sara. Similar to the buzz of voices heard from Haiti’s rural markets, the traveler knows when approaching a colony of madan sara because of the noisy din of chatter from hundreds of busy birds.

[ii] Purchasing Categories: The machann, market woman, is not especially interested in lobster and conch, both of which she cannot or does not dry. With regard to fish, she is interested in volume. There is some advantage for her regarding small fish, which are easier to clean and dry and less inclined then large fish to get worms after dried. Moreover, her rural clientele typically cannot distinguish Parrot Fish from a Grunt. Thus, the machann is not inclined to pay as much attention to fish types. The influence of the achtè, on the other hand, gives way to three categories of fish: Pwason Woz (Pink Fish), Pwason Blan (White Fish), Karabela (Blue Fish – in other areas of Haiti the category is sometimes “black”). The categories do not strictly correspond to the color of the fish but are more accurately explained as combination of size and type; both of which are market determined. Pink Fish are the most desirable; White Fish less desirable; Blue Fish–the small fish, juveniles, and rejects from the other categories–the least desirable. Lobster–the most lucrative product for both fisherman and achtè but not as commonly caught as fish–and conch fall into two categories: one for the internationally legal marketable size and another price category for undersized specimens.