As the Western third of the Caribbean’s second largest island, Haiti has a relatively small continental shelf surface area of 5,860 km2, approximately 20% the size of the entire country (27,750); but it has an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of mostly deep-sea that is 86,398 km2, three times the country’s landmass and including what could be one of the hemisphere’s major offshore fisheries (FAO, 2005; Advameg 2013). Yet, Haiti’s fishing industry is by contemporary standards based on simple and ancient techniques to an anthropologically fascinating extreme. As if looking back centuries if not millennia in time, fisher folk in Haiti are almost entirely focused on exploiting the limited shelf. The technology they use in this endeavor mostly rudimentary, artisanal strategies that yield small catches. Using the method described here, this paper provides a rapid summary of the informal artisanal fish value chain in Haiti. The research is based on extensive literature reviews; focus groups and a 109 household survey in the Grand Anse conducted in January 2018 on behalf of Heks-Eper; a series of 8 focus groups conducted in fishing communities Nippes in 2012 on behalf of the German Red Cross; and 15 months living in a North West Haiti fishing community in 1995-1996 funded by the National Science Foundation.

Artisanal Fish Ethnographic Value Chain in Haiti

Artisanal Fishing Overview

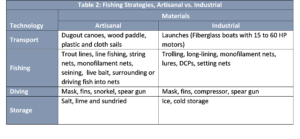

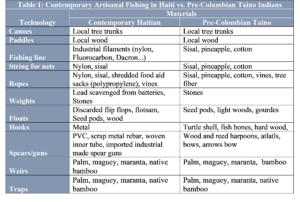

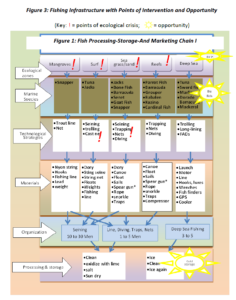

Of the some 26,000 fishing vessels that ply Haiti’s coast, only 1,200 are motor powered (MARNDR 2009). The majority are comprised of 14,000 dugout canoes and another 10,000 handcrafted wooden dories, all powered either by paddle or sail. The fishermen who occupy these vessels use technology that differs little from pre-Columbian fishing strategies: hooks, lines, bamboo traps, and fishing spears. Ambulant market women are the primary purchasers of the fish. They gut, clean, and dry the fish and then haul them by foot, on pack animal, motorcycle, in boat, or bus to inland markets. In total an estimated 52,000 men fish, while 20,000 women process and sell the fish. That is only about 12% of Haiti’s adult population, but the entire population benefits from an affordable and storable source of protein. For the some 3,000 to 5,000 fisherman who use modern industrial deep-sea fishing gear and who are oriented toward the high end urban market, there are 1,600 purchasers in the fishing communities linked to some 100 urban based fishing purchasing agencies, supermarket and restaurants.

Types of Fish

Fisherman in rural Haiti catch everything from tiny fish fit for an aquarium to 500 lb Marlin, porpoises and even an occasional whale shark. They sometimes classify fish by where they are caught. Artisanal fishman catch fish year-round, mostly juveniles or small, bony, fish not eaten on neighboring islands, and have low value on the international and urban market. Between June and January, the more desirable migratory Skip Jacks, Sardines, and Bonito are caught, sometimes in great number. Industrial fisherman also harvest migratory fish, but their focus includes epipelagic fish, those large predatory fish that hunt the uppers levels of the deep sea – specifically Marlin, Swordfish, Dorado, Wahoo, Sailfish, Mackerel, Snapper and various species of Tuna – and that have high value on the urban market.

After the fish have been caught they are classified for sale by the categories, Pwason Woz (Pink Fish), Pwason Blan (White Fish), Karabela (Blue Fish – in other areas of Haiti the category is sometimes “black”). The categories do not strictly correspond to the color of the fish but are more accurately explained as a combination of size and type; both of which are market determined. Pink Fish are the most desirable; White Fish less desirable; Blue Fish–the small fish, juveniles, and rejects from the other categories–the least desirable. Lobster–the most lucrative product for both fisherman and achtè but not as commonly caught as fish–and conch fall into two categories: one for the internationally legal marketable size and another price category for undersized specimens. Glass eels are another type of sea product that has become valuable in recent years (see ## for more detailed discussion).

Primary Stakeholders

Fisherman and market women.

Secondary Stake holders

Craftsmen who fix boats, nets and make traps. Sellers of hooks, nylon string for nets and other fishing gear. Owners of seines, FADs, NGOs, MARNDR.

Production[i]

Recently fishermen in the region have begun to engage in what can be called “industrial fishing strategies” made possible through the installation of offshore floating platforms called “Fish Aggregating Devices” (FADs) that attract large fish, making the location and capture of the fish vastly easier and more efficient. Nevertheless, an artisanal system prevails in the region and fisherman report it being more important for survival due to the fact that they can produce locally or scavenge whatever materials are necessary to engage in fishing and that artisanal fishing provides them with a more stable source of income. Despite the fact that what is being called “industrial” fishing yields much larger and more valuable fish, fisherman have not been able to fully exploit the opportunity due to limitations on storage (ice), transport (roads and vehicles larger than motorcycles) and market (demand is low and there is no single buyer who will purchase exceptionally large fish for shipment to the city). Nor is what we are calling industrial fishing sustainable without significant assistance from NGOs, as seen below.

Byproducts

Bone and Skin.

Production Technology

The use of “industrial” in this case refers to fiber-glass launches approximately 20 feet in length, open, but with outboard motors; long-line fishing gear; and monofilament nets. Industrial strategies can also include air compressors for deeper and more intensive spearfishing and gathering conch; and FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices). New processing and storage technologies include ice, coolers, electric freezers, and cold storage rooms for preservation, motor boats for rapid and safer transport both to offshore fishing grounds and to the urban market. Acquiring all these materials has only been possible with significant support from NGOs and after some 10 years of support, fisherman in the region are no closer to making the industrial strategy sustainable than they were when they started. Nor has the investment itself been complete. The continuing lack of cold storage has meant that many fish spoil.

Organization

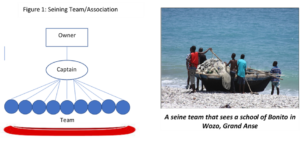

Industrial fishing is organized around the association which is almost entirely dependent on financial assistance from foreign aid agencies. Three to five men will use the association-owned or subsidized boat and motor, the association-owned or subsidized fishing gear and fish the association-owned FAD. In contrast, artisanal fishing is mostly an autonomous or single-owner enterprise that involves one to three fishermen. It reaches its organizational zenith with the seine which is a team effort that requires major investments (a dory and seine), vigilance (looking out for schools of fish), timing (getting the team, boats and seine into the water before the fish escape), and coordination (putting the seine into the water, surrounding the fish, and then hauling them to shore or into the boat). Thus, the organization necessary to seine usually involves the met (the person who has invested in the seine and boat), a kapten (captain who coordinates), and an ekip (a team of from 8 to 30 men). Emphasizing the significance of this natural organization, artisanal fishermen in Wozo – who like all fishermen in the region have a keen interest in trying to capture an international sponsor who will underwrite their transition into industrial fishing – explained that, “every seine is an association.”

Hiring

With the exception of repairing equipment– repairing wooden boats, making canoes and mending nets– fisherman typically do not hire labor. The catch is divided into thirds: one third for the owner of the boat, one third for the captain, and the rest divided among the crew. If the fisherman fish at a FAD, they are also supposed to pay the owner of the FAD—typically an association–a portion of the catch (1/5th the catch).

Tenure

Boats and fishing equipment such as nets and compressors are typically owned by men. Some women purchase nets and traps—invariably wives or mothers of fishermen. Traps may be purchased and fished even in the name of children, i.e. to pay school expenses for them. The most expensive and prized technologies are outboard motors, fiberglass boats and seines—nets that may be 100 to 200 meters in length. FADs are typically underwritten by NGOs and owned by fishing associations, although some are increasingly owned by private entrepreneurs.

Financial underwriters

Aid agencies—such as the UN agencies, PADI, Food for the Poor, HEKS-EPER, ACDI-VOCA—have all participated in underwriting the costs of industrial fishing (see ##). Artisanal fishing, on the other hand, underwritten by the individual, family, friends, and patron (Big Man/Woman). Fisherman typically underwrite the market chain by giving credit to female vendors, usually along lines of kinship.

Source of financing

Principally gardens and livestock.

Most Important Relationship Production

Fishing partners, boat ownership, male producer and female vendor (credit).

Sexual and Age Division of Labor

Men fish. Women and children gut and clean, and sometimes salt and dry the fish. Until recently the sale of fish was entirely a female undertaking. Recently however, the mostly male “achte” has appeared. The “achte” have emerged as byproducts of NGOs and they reflect the tendency for NGOs to give market opportunities to men, more so than women, thereby cutting into the traditional female marketing activities. The achte is a well capitalized purchaser who buys fresh fish and ships them to the city for resale.

Sale

Fish are sold locally for household consumption or to be prepared and resold as street food or in informal restaurants. They are also dried and transported to rural markets, Jeremy and even Port-au-Prince. Women in the focus groups who sell fish report it as their preferred trade. But unless a woman has capital to invest in fish and is willing to risk her money, engaging in fishing depends on having a husband, lover, son or other male relative who will give the fish on credit. When taken on credit the woman typically adjusts prices after the fact to account for her profits and/or losses.

Marketing organization

Women sell individually. No pooling of financing, few lenders.

Measurement

Small fish are measured in both volume and quantity. They are typically purchased by the basket or plastic basin (volume), then put on strings and sold by the string (quantity), typically with five to ten fish to a kod. Larger fish are bought and sold by volume. They are purchased wholesale based the size of the fish and then retailed by tranch (slice).

Processing and storage

Traditionally women gut and de-scale fish, wash them with lime, salt them and sun dry them. The fish can then be stored indefinitely. The women hang them from the rafters in their homes or store them in polyethylene and sometimes burlap sacks until the woman has enough fish for a voyage to market to be profitable, the conditioning factor being the cost of transportation. Fish can also be stored on ice. However ice is only a temporary solution. There are few cold storage rooms in Haiti those that exist are costly and require backup generators, i.e. they typically are not working. The fish must be sold quickly or dried.

Transport and Market Venue

The fish are packed into sacks and hauled to a rural market by foot or on the back of a pack animal, on motorcycle to provincial market, or sometimes on public bus or truck to Port-au-Prince. Focus group participants report that high end restaurants and supermarkets do not purchase their fish.

Price and Profit (Value added line)

Final point of sale in provincial urban or rural markets has a ~50 percent markup on the original cost of the fish. Sales in Port-au-Prince are ~100 percent of original costs.

Consumers

Consumers are the general population. During Easter the demand for fish spikes in the city and some woman will make the voyage to Port-au-Prince at this time.

Afflictions

Problems with fish include ciguatera poisoning that may result from eating predator reef fish and scombroid poisoning from larger pelagic fish that have not been properly iced.

Opportunities

There are enormous possibilities for production and marketing of fish in Haiti: 70% of Haiti’s estimated consumption of 20,000 MT year fish are imported.iii Yet, per capita consumption of fish in Haiti is estimated to be 4.5 kg, compared to a global average of more than 18 kg. The suggestion is a national market potential of as much as 100,000 MT per year, five times current consumption. HACCP certification–an international standard defining the requirements for effective control of food safety would open up exports to the Dominican Republic, creating an even greater market potential. i

Seafood: Ice, Urban markets and Export

A significant and highly lucrative opportunity exists for selling high quality pelagic fish to Port-au-Prince supermarket, restaurants and for export overseas. The installation of more than 120 FAD over the past 10 years have made the opportunity possible. Fishermen in Haiti pull in an unknown but catch of these high value fish. Many spoil. Currently there is insufficient ice available at fishing launch points throughout Haiti and no system for rapidly exporting the fish to the cities. Yet, all Haitian cities have the infrastructure to support an ice plant and the recently improved roads between many cities means there that more almost always daily buses and a steady flow smaller vehicles make the trip to Port-au-Prince. Some Haiti provincial cities are also service by small aircraft the use of which can be justified by the potentially high profits from pelagic fish at Port-au-Prince restaurants and supermarket.

Fish Farming

Another significant opportunity, one that focuses more on providing the local rather than the urban market with protein rich source of fish, is freshwater fishculture. Fishfarming of Tilapia and Common Carp began in Haiti as early as 1951 with a collaborative FAO/MARNDR five-year fish-farming project that imported Common Carp from Alabama USA and Tilapia Mossambica from Jamaica. The fish were used to stock rivers, lakes and irrigation canals.. Restocking occurred annually until 1967. In the 10 years 1958 to 1968, 4,824 fish ponds, each of an area of ~100 m2 , were built in various regions of Haiti—mostly on the Artibonite–and stocked with 798,669 Carp fingerlings and 815,765 Tilapia Mossambica. It was these stocking programs that led to current existence of Carp and Tilapia in the rivers of the Grand Anse (see Photo 18.2, right).

Some efforts at fish cultivation were made by FAO in 1989-90, notably with construction of a Government/MARNDR managed hatchery in the Artibonite, but for the most part cultivation of fish in Haiti languished in the 1970s and all but disappeared until the early 2000s when it experienced a resurgence through NGOs.i

Most promising is Taino Fish Ferme on lake Azuei and Operation Blessing hatchery in Port-au-Prince. Another hatchery in Port-au-Prince, Caribbean Harvest, much hyped on the internet, has a questionable—if not mostly fraudulent—track record of producing fingerlings (see Landell Mills. 2012).

There is also currently a hatchery with a 200,000 fry capacity under construction in the Department of the North East at Lagon aux Boeufs sponsored by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Ministry of Agriculture. Assistance with fishfarming startup operations can be procured through Organizations such as Farmer-to-Farmer and Aquaculture without Frontiers.

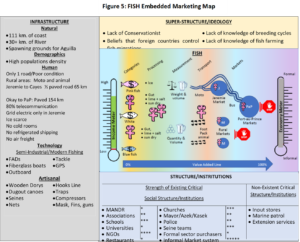

Fish Marketing and Value Chain Maps

Below are a series of largely self-explanatory fish value chain and marketing maps produced using the MEVMS (Multidimensional Ethnographic Value Chain Mapping Strategy).

Bibliography

Advameg, Inc Encyclopedia of the Nations. Haiti Fishing

http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Americas/Haiti-FISHING.html

Abe, Valentin Ph.D. Undated. Risk Management in Aquaculture: Case Study of Haiti. Caribbean Harvest Foundation. Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Abe, Valentin Ph.D. 2014. Risk Management in Aquaculture: Case Study of Haiti. Executive Director, Caribbean Harvest Foundation. Port-au-Prince, Haiti. http://www.agriskmanagementforum.org/content/risk-management-aquaculture-case-study-haiti

Attfield, Harlan H. D. Goats…. with Contributions From: George F.W. Haenlein, Jane Williams, Earl M. Moore Technical Reviewers: Morrison Lowenstein, Pam Adolphus

Berman, Mary Jane, and Charlene Dixon Hutcheson, 2000 “Impressions of a Lost Technology: A Study of Lucayan-Taino Basketry.” Wake Forest University Winston-Salem, North Carolina Documento descargado de Cuba Arqueológica www.cubaarqueologica.org

Brethes. J-C. et C. Rioux. 1986. La pêche artisanale en Haïti. Situation actuelle et perspectives de développement in La pêche maritime. 65 (1302) : 652-658p.

Celestin, W. 2004. La filière pêche dans le département de la grand’ anse d’Haïti. Pour le groupe d’action et de recherche en développement local (GARDEL). Projet PDR-GA.364p.

Chambers and Associates 2010 Headed for Extinction? http://www.bigmarinefish.com/extinction.html

Child, R.D., et al.. Arid and Semiarid Lands: Sustainable Use and Management in Developing Countries. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1984. Also, Morrilton, Arkansas: Winrock International, 1984.

Chounoune, F. Jackson. 1998 Fish Culture Projects. Bulletin vol 11 n°1 Some fisheries and aquaculture projects in Haiti. International Center for Aquaculture Auburn University Agricultural

CIAT (Comité Interministériel IAT d’Aménagement du Territoire) 2012 http://ciat.gouv.ht/sites/default/files/docs/CIAT_CIATs_mission_GB.pdf

CRFM 2009 CARIBBEAN REGIONAL FISHERIES MECHANISM SECRETARIAT

CRFM 2009 CARIBBEAN REGIONAL FISHERIES MECHANISM SECRETARIAT REPORT OF THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY SURVEY OF THE FISHERIES OF HAITI Funded by the Commission of the European Union Under Lomé IV – Project No. 7: ACP: RPR: 385

Damais, G., P. de Verdilhac, A. Simon et D.S. Celestin. 2007. Étude de la filière de pêche en Haïti : IRAM /INESA. Rapport provisoire. 116p

FAFO 2001 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume II

FAFO 2003 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume I

FAO (2005). Fishery Country Profil. La Republique d’Haiti. Donnees economiques generales. Disponible sur: http://www.fao.org/fi/oldsite/FCP/fr/HTI/profile.htm

Guinette, Marie Pascale Saint Martin François, 2009 “La pêche sur Dispositif de Concentration de Poissons (DCP) à Anse d’Hainault: Contribution au Revenu des Marins Pêcheurs et Marge des Distributeurs.” Mémoire de fin d’études agronomiques Faculte D’agronomie Et De Medecine Veterinaire (Famv), Université d’état d’Haïti Departement Des Ressources Naturelles Et Environnement.

Hargreaves, John A. 2012. Developing Tilapia Aquaculture In Haiti: Opportunities, Constraints, And Action Items Proceedings Of A Workshop Sponsored By Novus International, Aquaculture Without Frontiers, The World Aquaculture Society, And The Marine Biological Laboratory Edited. Aquaculture Assessments LLC

IDB 2014 HAITI Project Profile (PP) Land Tenure Security Program HA-L1056 http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=35624298

IDB/MIF 2010 Mango As An Opportunity For Long-Term Economic Growth Document Of The Inter-American Development Bank Multilateral Investment Fund (Ha-M1034). Donors Memorandu

Wiener, John. 2013. “Creole Words And Ways: Coastal Resource Use and Local Resource Knowledge In Haiti J. Wiener, Fondation Pour La Protection De La Biodiversité Marine, Port Au Prince, Haiti.

Jumelle, I. C. 1984. Pêche et pêcherie en Haïti. Formulation d’un projet d’amélioration. 115p.

Killworth, Peter D, Eugene C. Johnsen, H.Russell Bernard, Gene Ann Shelley, and Christopher McCarty. 1990. Estimating the Size of Personal Networks. In Social Networks 12:289-312. North Holland.

Landell Mills. 2012 Final technical report STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT OF AQUACULTURE POTENTIAL IN HAITI, 2012 Project Ref. Number: N° CAR/3.1/B12 Region: Caribbean Country: Haiti October 2012 Project implemented by: Landell Mills “Strengthening Fisheries Management in ACP Countries

LEVE 2014. Value Chain Assessment Annex 3. Agribusiness Sector Assessment Local Enterprise and Value Chain Enhancement (LEVE) Project https://haitileveproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Annex-3.-LEVE-Agribusiness-Sector-Assessment.pdf

LEVE. 2016. Report on Local Fish Feed Production Opportunities LOCAL ENTERPRISE AND VALUE CHAIN ENHANCEMENT (LEVE) PROJECT. RTI International

Locher, U. 1988. Land distribution, land tenure and land erosion in Haiti. Paper presented at the Twelfth Annual Conference of the Society for Caribbean Studies, July 12–14, High Leigh Conference Centre, Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, UK.

Lovell, R.T. and D.D. Moss. 1971. Fishculture Survey Report for Haiti International Center for Aquaculture and Fisheries and Allied Aquacultures. Auburn University, Alabama.

MARNDR 2007 Etude de la filière pêche en Haïti et propositions de stratégie d’appui au secteur Institut de Recherche et d’Applications des Méthodes. PROGRAMME DE DÉVELOPPEMENT RURAL DES ZONES CENTRE ET SUD D’HAÏTI. Gilles Damais, Philippe de Verdilhac, Anthony Simon, Dario Styve Célestin

MARNDR 2010. Programme National pour le Développement de L’Aquaculture en Haïti 2010-2014.

Matthes, Hubert. 1988. Evaluation de la Situation de la Pêche sur les Lacs en Haiti. Augumentation de la production de poissons en Haitipar l’Aquaculture et la Peche Continentale. FAO Project HAI/88/003. 48 p.

McLain, R.J., D.M. Stienbarger, and M.O. Sprumont. 1988. Land tenure and land use in southern Haiti: Case studies of the Les Anglais and Grande Ravine du Sud watersheds. LTC Research Paper 95. Madison: Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin- Madison. Mimeo.

Miller, James. 2015. Rapid Fisheries Sector Assessment – Three Bays National Park. The Nature Conservancy Report. 49 p.

Programme National de Lacs Collinaires. 2012. Report on 100 Lacs Collinaires Constuit par le programme Nationale. 132 p. (Wilson Celestin managed this program which constructed 100 lakes).

Quinlan, M. 2005. Considerations for collecting freelists in the field: Examples from ethnobotany. Field Methods 17 (3): 219–34.

Reef Check 2011 “Haiti’s Reefs Most Overfished in the World” Post date : 2011-03-30 http://reefcheck.org/news/news_detail.php?id=726

REPORT OF THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY SURVEY OF THE FISHERIES OF HAITI Funded by the Commission of the European Union Under Lomé IV – Project No. 7: ACP: RPR: 385

Romelus, Zacharie. 2005. Pêche maritime et sa contribution dans le revenu des agro pêcheurs de la commune d’Anse d’Hainault. 45p.

Sinn, Rosalee, Raising Goats for Milk and Meat. Little Rock, Arkansas: Heifer Project International, 1984.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2018. Baseline, Value Chains, & Notab Information Network. Socio-Dig, Heks-Eper Report for the Grand Anse.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2012. Post Sandy Fishing Assessment for Grand Anse and Nippes. German and Haitian Red Cross.

Soderberg, R.W. 2014. Environmental Assessment for Lake Azuei Tilapia Cage Farm. 12 p.

USAID. 2006. Proceedings of the Fish Feeds Forum. Fisheries Investment for Sustainable Harvest Project. USAID. Coop. Agreement: 617-A-00-05-00003-00. Auburn Fisheries Dept.

Tessier, E. 1995. Elaboration d’un suivi des statistiques de pêche pour la Réunion. DOC. ASS. Thon, IFREMER, la Réunion,27p.

NOTES

[i] Although petty in terms of international standards, fishing represents a significant part of the household livelihood strategy for some 250,000 men, women and children in Haiti, approximately 25,000 of whom are located in the Grand Anse (MARNDR 2009). The people who live in the fishing communities tend to be among the least educated people in the region and live in marginalized and remote communities. An estimated 92% have not finished high school – compared to 75% nationally (CRFM 2010; EMMUS 2012).