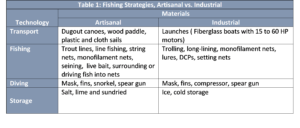

Of the some 26,000 fishing vessels that were plying Haiti coast in 2018, only about 1,200 were involved in what can be called “industrial fishing strategies.” The reader should take note that this is distinct from the modern fisheries using megaton steel ships and massive nets with hydraulic powered wenches and onboard machine powered cold storage. The use of “industrial” refers here to fiber-glass launches approximately 20 feet in length, open, but with outboard motors; long-line fishing gear; and monofilament nets. Nevertheless, while simple in comparison to the developed world version of modern industrial fishing fleets, the modern Haitian fishing and marketing system versus the artisanal system the continues to prevail in Haiti (read here) are significantly different in terms of dependency on outside sources of materials and technology, fishing strategies, investment, returns, market chains, income and the impact they have on the environment as well as the lives of the people involved. In the pages that follow we briefly describe the modern industrial production and marketing strategies. The research is based on extensive literature reviews; focus groups and a 109 household survey in the Grand Anse conducted in January 2018 on behalf of Heks-Eper; a series of 8 focus groups conducted in fishing communities Nippes in 2012 on behalf of the German Red Cross; and 15 months living in a North West Haiti fishing community in 1995-1996 funded by the National Science Foundation.

Industrial Fishing Value Chain in Haiti

Industrial Fishing

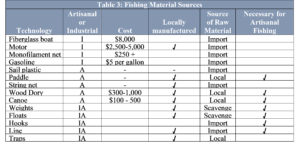

Although relatively recent—emerging over the past 20 years–modern industrial fishing technologies are evident to today varying degrees in most fishing communities in Haiti. The fishing technologies include fiberglass boats and outboard motors that permit offshore capture of larger fish that that are in greater demand in the high end urban market; imported monofilament nets that more effectively snare fish; air compressors for deeper and more intensive spearfishing and gathering conch; and offshore floating platforms called “Fish Aggregating Devices” (FADs) that attract large fish making the location and capture of the fish vastly easier and more efficient. New processing and storage technologies include ice, coolers, electric freezers, and cold storage rooms for preservation, motor boats for rapid and safer transport both to offshore fishing grounds and to the urban market. All of this seems intuitively advantageous to everyone involved: fishermen, marketers, buyers and the regional economy. But, as will be seen, it may be that conditions in Haiti make the endeavor costly, risky, and economically unsustainable in the absence of major investments from the international community.

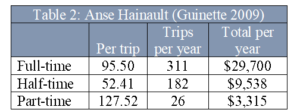

The modernization of fishing is linked, if not dependent on, the formation of associations and cooperatives. These organizations tend to be dominated by traditional elites, politicians, and urban oriented entrepreneurs (see Weiner 2005 for example); they are heavily subsidized with funds from the international community; and to date, they include only a small minority of the total fishing population. It is nevertheless an area that shows promise. The impact is best exemplified by success in Grand Anse communities of d’Anse d’Hainault, de Dame Marie et des Irois Anse. In 2000 the European Union and MARNDR supported the formation of two local associations, provided access to fishing gear and cold storage, and installed DCPs. By 2008, 68% of fisherman in the area had outboard motors; fulltime fishermen were earning an estimated US$29,700 per year (Guinette 2009; see Table).

The impact is best exemplified by success in Grand Anse communities of d’Anse d’Hainault, de Dame Marie et des Irois Anse. In 2000 the European Union and MARNDR supported the formation of two local associations, provided access to fishing gear and cold storage, and installed DCPs. By 2008, 68% of fisherman in the area had outboard motors; fulltime fishermen were earning an estimated US$29,700 per year (Guinette 2009; see Table).

Pros and Cons of Artisanal vs. Industrial Fishing

For the fishermen, industrial offshore fishing seems to have obvious advantages. Artisanal fishermen are limited in range. They lack outboard motors; their vessels are fragile and unfit for the open sea. They lack portable cold storage. This means the artisanal fisherman must stay close to shore. The size of fish he can catch is limited as well. Even when the artisanal fisherman manages to hook a large fish he is often unable to pull it aboard, as he may capsize in the process or get pulled out to sea trying to hold on to the fish.

Thus it seems evident that industrial deep-sea fishing is eminently more advantageous to fishermen. Moreover, a concern in terms of interventions that target artisanal fishermen is its ecological impact on the coastal shelf. In the past 30 years the number of artisanal fishermen exploiting the Haiti’s shelf went from 11,000 in 1985 to 30,000 in 2001 to over 50,000 in 2010.[i] It is a 5 fold increase. Coupled with the complete absence of any controls on fishing areas, size and age of the fish caught, and compounded by extreme erosion and consequent muddy runoff from streams and rivers that smothers reefs and destroys fish habitat, Haiti’s shelf is said to be in a state of extreme ecological crisis. Reef Check, an international volunteer agency that has taken on the responsibility of monitoring the ecological status of reefs throughout the world, has identified Haiti as having, “the most overfished reefs in the world” (Reef Check 2001). [ii]

So the apparent ecological unsustainability of Haiti’s current artisanal fishery seems to point the way toward offshore fishing. This means FADs, fiberglass boats, and access to high end urban markets. But for the GRC and international organizations sensitive to negative publicity and environmental crisis, there are problems here as well. First off, throughout the world, stocks of large offshore predatory fish have been declining precipitously now for at least the past 4 decades. Some studies indicate declines in Billfish– the fish that Haiti’s new fishermen aim to catch –have declined by 65 to 98 percent in the past 40 years (Chambers and Associates 2010). Questions have been raised in this context about the role of FADs. Greenpeace calls them “deadly fish magnets” that are driving deep sea fish beyond the point-of-no-return. Environmental activists are lobbying for quotas and prohibitions. Many people in the developed world are listening. Among them are surely many Red Cross donors.[iii] [iv]

Another issue is the costs associated with offshore fishing and who has been paying them. Investment in the industrial fishing gear, boat and motor necessary for a single equipped vessel generally exceeds US$20,000. Cold storage is another cost. FADs are anchored, preferably with chain, to the bottom of the sea at depths of 1,000 feet or more. Someone has to pay for all of this. Seafood imports from Haiti were long ago banned in both the US and Europe because phytosanitary concerns, which means that Haitian fishing attracts little corporate financial investment from outside the country (MARNDR 2009). The Haitian state makes no investments in fishing. It is unable on its own to accomplish the task and will remain that way for the foreseeable future. For a lucky few fishermen, costs have been subsidized by international aid organizations, as in the case of d’Anse d’Hainault, Dame Marie et Irois Anse in the Sourth of Haiti, and in communities elsewhere in Haiti.

The point is that the industry is being financed with aid, to the extent that it is being funded at all. Anse d’Hainault region is an excellent example. The offshore industrial fishing industry began there in 2000 with EU financing: 132 outboard motors were sold on credit and subsidized at 50% of cost; 10 DCPs were installed; a credit fund was provided as well as cold storage facilities and materials. Fishermen responded. The number of offshore fishing vessels in the area went from 120 in 1997 to 220 in 2007 (Damais et al, 2007; (Guinette 2009). In 2008, Food for the Poor reportedly gave each of the three communities an additional 24-foot fiberglass boats with outboard engines, 100-quart coolers, safety equipment, global positioning system (GPS) fish finders and kerosene freezers to store catches.[v]

The role that aid plays in initiating the formation of fishing associations is clear. When the EU first began financing Anse Hainault, there was no fishing association. L’Association des Jeunes d’Anse d’Hainault converted itself into « Pêche Anse d’Hainaut Irois », or PADI, becoming the major recipient of boats, motors and securing access to the DCPs. Two years later, in 2002, the AMPAH (Association des Marins Pêcheurs d’Anse d’Hainault) was formed as an offshoot and co-recipient of the funds. In 2013, short before this report was written, representatives of one of these associations sought additional funding and subsidizing from the Red Cross (based on report from Red Cross field manager), highlighting the likelihood that without influx of aid to the fishermen, investments would not have been made in the first place. And without continued support, it’s hard to see how the industry can be sustained. [vi]

There is also the issue of the stability of access to urban markets. While Haiti imports 70% of the fish consumed in the country (see MARNDR 2009), there is still the difficulty of getting high quality local fish to the Port-au-Prince market. Contacts, entrepreneurs, investments in time, storage and transport has all been subsidized and expedited by overseas aid agencies and foreign donors.

To understand why Haitians themselves never invested in an industrial fishing sector, one has to turn to Haiti’s poor infrastructure, precarious urban market, and tumultuous political landscape (see ##). But for the purposes of this paper, the dependency on foreign aid to establish and sustain what could be a highly lucrative enterprise should give us pause. We should ask if the industry is now sustainable or will be in the foreseeable future. The ultimate question in this regard will be whether local associations, government and entrepreneurs will at some point assume the costs and responsibility for the system necessary to make it sustainable or if, as so often occurs with projects in Haiti, the industry will only endure as long as international donors subsidize it.

Indeed, it is noteworthy in this regard that while all along the coast one sees locally handcrafted canoes and dories with men working hard at artisanal fishing, there is a conspicuous absence of modern boats. In all of Haiti, less than 5% of fisherman can aptly be classified as industrial fisherman (MARNDR 2009; Guinette 2009). If the traveler goes ashore, in almost every fishing village in Haiti, he or she can collect the stories of failure and see the discarded and deteriorating hulls of fiberglass boats from past projects.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Advameg, Inc Encyclopedia of the Nations. Haiti Fishing

http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Americas/Haiti-FISHING.html

Abe, Valentin Ph.D. Undated. Risk Management in Aquaculture: Case Study of Haiti. Caribbean Harvest Foundation. Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Abe, Valentin Ph.D. 2014. Risk Management in Aquaculture: Case Study of Haiti. Executive Director, Caribbean Harvest Foundation. Port-au-Prince, Haiti. http://www.agriskmanagementforum.org/content/risk-management-aquaculture-case-study-haiti

Attfield, Harlan H. D. Goats…. with Contributions From: George F.W. Haenlein, Jane Williams, Earl M. Moore Technical Reviewers: Morrison Lowenstein, Pam Adolphus

Berman, Mary Jane, and Charlene Dixon Hutcheson, 2000 “Impressions of a Lost Technology: A Study of Lucayan-Taino Basketry.” Wake Forest University Winston-Salem, North Carolina Documento descargado de Cuba Arqueológica www.cubaarqueologica.org

Brethes. J-C. et C. Rioux. 1986. La pêche artisanale en Haïti. Situation actuelle et perspectives de développement in La pêche maritime. 65 (1302) : 652-658p.

Celestin, W. 2004. La filière pêche dans le département de la grand’ anse d’Haïti. Pour le groupe d’action et de recherche en développement local (GARDEL). Projet PDR-GA.364p.

Chambers and Associates 2010 Headed for Extinction? http://www.bigmarinefish.com/extinction.html

Child, R.D., et al.. Arid and Semiarid Lands: Sustainable Use and Management in Developing Countries. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1984. Also, Morrilton, Arkansas: Winrock International, 1984.

Chounoune, F. Jackson. 1998 Fish Culture Projects. Bulletin vol 11 n°1 Some fisheries and aquaculture projects in Haiti. International Center for Aquaculture Auburn University Agricultural

CIAT (Comité Interministériel IAT d’Aménagement du Territoire) 2012 http://ciat.gouv.ht/sites/default/files/docs/CIAT_CIATs_mission_GB.pdf

CRFM 2009 CARIBBEAN REGIONAL FISHERIES MECHANISM SECRETARIAT

CRFM 2009 CARIBBEAN REGIONAL FISHERIES MECHANISM SECRETARIAT REPORT OF THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY SURVEY OF THE FISHERIES OF HAITI Funded by the Commission of the European Union Under Lomé IV – Project No. 7: ACP: RPR: 385

Damais, G., P. de Verdilhac, A. Simon et D.S. Celestin. 2007. Étude de la filière de pêche en Haïti : IRAM /INESA. Rapport provisoire. 116p

FAFO 2001 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume II

FAFO 2003 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume I

FAO (2005). Fishery Country Profil. La Republique d’Haiti. Donnees economiques generales. Disponible sur: http://www.fao.org/fi/oldsite/FCP/fr/HTI/profile.htm

Guinette, Marie Pascale Saint Martin François, 2009 “La pêche sur Dispositif de Concentration de Poissons (DCP) à Anse d’Hainault: Contribution au Revenu des Marins Pêcheurs et Marge des Distributeurs.” Mémoire de fin d’études agronomiques Faculte D’agronomie Et De Medecine Veterinaire (Famv), Université d’état d’Haïti Departement Des Ressources Naturelles Et Environnement.

Hargreaves, John A. 2012. Developing Tilapia Aquaculture In Haiti: Opportunities, Constraints, And Action Items Proceedings Of A Workshop Sponsored By Novus International, Aquaculture Without Frontiers, The World Aquaculture Society, And The Marine Biological Laboratory Edited. Aquaculture Assessments LLC

IDB 2014 HAITI Project Profile (PP) Land Tenure Security Program HA-L1056 http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=35624298

IDB/MIF 2010 Mango As An Opportunity For Long-Term Economic Growth Document Of The Inter-American Development Bank Multilateral Investment Fund (Ha-M1034). Donors Memorandu

Wiener, John. 2013. “Creole Words And Ways: Coastal Resource Use and Local Resource Knowledge In Haiti J. Wiener, Fondation Pour La Protection De La Biodiversité Marine, Port Au Prince, Haiti.

Jumelle, I. C. 1984. Pêche et pêcherie en Haïti. Formulation d’un projet d’amélioration. 115p.

Killworth, Peter D, Eugene C. Johnsen, H.Russell Bernard, Gene Ann Shelley, and Christopher McCarty. 1990. Estimating the Size of Personal Networks. In Social Networks 12:289-312. North Holland.

Landell Mills. 2012 Final technical report STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT OF AQUACULTURE POTENTIAL IN HAITI, 2012 Project Ref. Number: N° CAR/3.1/B12 Region: Caribbean Country: Haiti October 2012 Project implemented by: Landell Mills “Strengthening Fisheries Management in ACP Countries

LEVE 2014. Value Chain Assessment Annex 3. Agribusiness Sector Assessment Local Enterprise and Value Chain Enhancement (LEVE) Project https://haitileveproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Annex-3.-LEVE-Agribusiness-Sector-Assessment.pdf

LEVE. 2016. Report on Local Fish Feed Production Opportunities LOCAL ENTERPRISE AND VALUE CHAIN ENHANCEMENT (LEVE) PROJECT. RTI International

Locher, U. 1988. Land distribution, land tenure and land erosion in Haiti. Paper presented at the Twelfth Annual Conference of the Society for Caribbean Studies, July 12–14, High Leigh Conference Centre, Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, UK.

Lovell, R.T. and D.D. Moss. 1971. Fishculture Survey Report for Haiti International Center for Aquaculture and Fisheries and Allied Aquacultures. Auburn University, Alabama.

MARNDR 2007 Etude de la filière pêche en Haïti et propositions de stratégie d’appui au secteur Institut de Recherche et d’Applications des Méthodes. PROGRAMME DE DÉVELOPPEMENT RURAL DES ZONES CENTRE ET SUD D’HAÏTI. Gilles Damais, Philippe de Verdilhac, Anthony Simon, Dario Styve Célestin

MARNDR 2010. Programme National pour le Développement de L’Aquaculture en Haïti 2010-2014.

Matthes, Hubert. 1988. Evaluation de la Situation de la Pêche sur les Lacs en Haiti. Augumentation de la production de poissons en Haitipar l’Aquaculture et la Peche Continentale. FAO Project HAI/88/003. 48 p.

McLain, R.J., D.M. Stienbarger, and M.O. Sprumont. 1988. Land tenure and land use in southern Haiti: Case studies of the Les Anglais and Grande Ravine du Sud watersheds. LTC Research Paper 95. Madison: Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin- Madison. Mimeo.

Miller, James. 2015. Rapid Fisheries Sector Assessment – Three Bays National Park. The Nature Conservancy Report. 49 p.

Programme National de Lacs Collinaires. 2012. Report on 100 Lacs Collinaires Constuit par le programme Nationale. 132 p. (Wilson Celestin managed this program which constructed 100 lakes).

Quinlan, M. 2005. Considerations for collecting freelists in the field: Examples from ethnobotany. Field Methods 17 (3): 219–34.

Reef Check 2011 “Haiti’s Reefs Most Overfished in the World” Post date : 2011-03-30 http://reefcheck.org/news/news_detail.php?id=726

REPORT OF THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY SURVEY OF THE FISHERIES OF HAITI Funded by the Commission of the European Union Under Lomé IV – Project No. 7: ACP: RPR: 385

Romelus, Zacharie. 2005. Pêche maritime et sa contribution dans le revenu des agro pêcheurs de la commune d’Anse d’Hainault. 45p.

Sinn, Rosalee, Raising Goats for Milk and Meat. Little Rock, Arkansas: Heifer Project International, 1984.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2018. Baseline, Value Chains, & Notab Information Network. Socio-Dig, Heks-Eper Report for the Grand Anse.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2012. Post Sandy Fishing Assessment for Grand Anse and Nippes. German and Haitian Red Cross.

Soderberg, R.W. 2014. Environmental Assessment for Lake Azuei Tilapia Cage Farm. 12 p.

USAID. 2006. Proceedings of the Fish Feeds Forum. Fisheries Investment for Sustainable Harvest Project. USAID. Coop. Agreement: 617-A-00-05-00003-00. Auburn Fisheries Dept.

Tessier, E. 1995. Elaboration d’un suivi des statistiques de pêche pour la Réunion. DOC. ASS. Thon, IFREMER, la Réunion,27p.

NOTES

[i] Drawing on CRFM’s 2010 evaluation of fishing in Haiti, The National Fisheries Service estimates that 21,000 (60%) of these are full time fishers, whilst the rest 6,000 (40%) are part-time fishers. When one follows the trend over the past two decades, the estimates are as follows: 1985 – 11,000 (www.cam.org); 1989 – 12,000 (UNDP / FAO); 1999 – 17,148 (FAO); 2001-30,000; in 2010 MARNDR put it at 52,000

[ii] Haiti’s Reefs Most Overfished in the World Post date : 2011-03-30

http://reefcheck.org/news/news_detail.php?id=726

[iii] Having said that, all Haitian fisherman combined currently catch less Pelagic fish than a major industrial fishing boat; and the temporary relief for the shelf and the economic interest that would come from offshore fishing could galvanize Haitian interest in conservation–I said “could.”

[iv] see, Green Peace Blogs: http://www.greenpeace.org.au/blog/?p=77 and http://www.greenpeace.org/australia/en/news/oceans/What-is-sustainable-tuna/

[v] For Food for the Poor boats, see Net News 2008 “Florida charity changes lives in Haiti”

http://www.caribbeannewsnow.com/caribnet/haiti/haiti.php?news_id=5627&start=1040&category_id=2