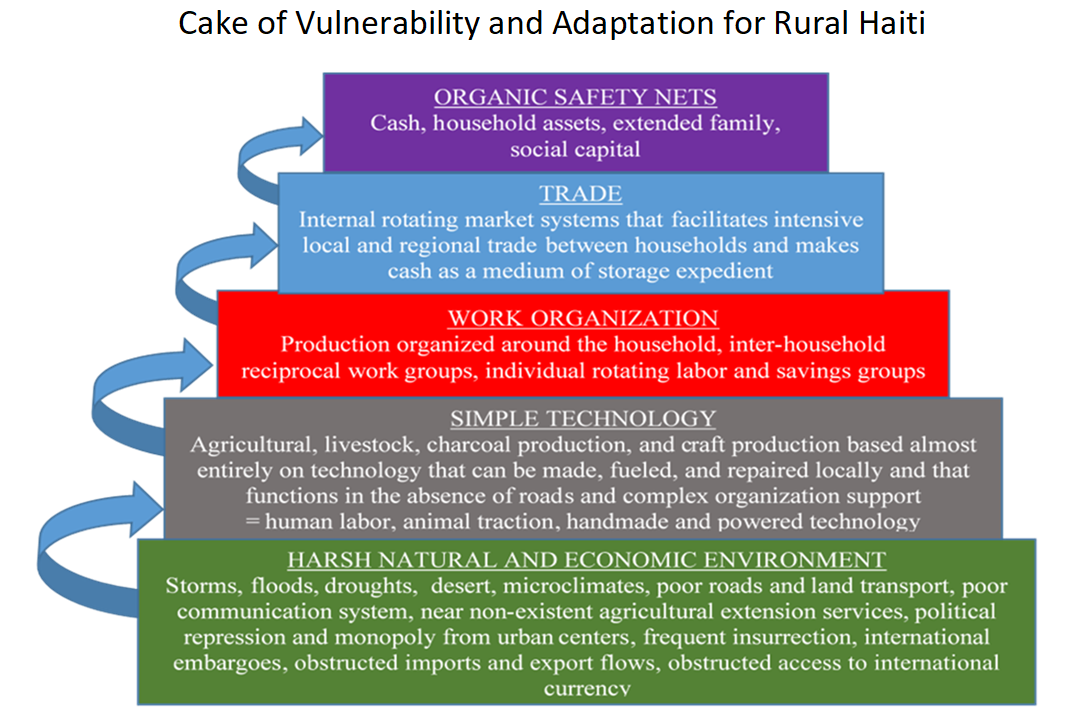

Here are a series of diagrams intended to make the prevailing rural Haitian household livelihood strategies easily understandable. The first diagram, above, is what we are calling, “The Cake of Vulnerability.” It is a model reminiscent of Marx’s Infrastructure, Structure and Super-structure description of modern human social organization. Here it is inspired by the more elaborate model of Cultural Materialism (for application of CM theory in humanitarian aid see this article) as well as anthropologist Leslie White’s “Cake of Culture.” It is a causal model and the direction of causation–indicated by the arrows–should be read from the bottom up, each layer determining the conditions or responses in the layer above it.

Haiti Anthropology Brief: Cake of Vulnerability and Adaptation to Poverty

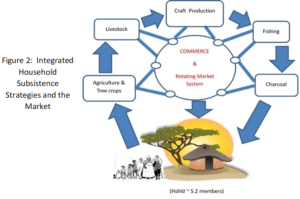

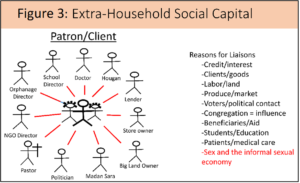

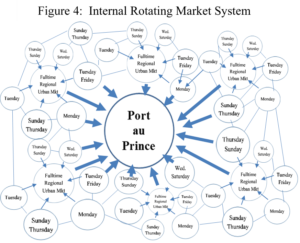

The crux of the argument is that the household as a productive enterprise is the principal mechanism for individual social security in rural Haiti and rests on low-risk, minimal investment agricultural and livestock, harvesting of fruits, charcoal production, fishing, production of simple crafts (such as baskets, tack, mats) and part-time engagement in remunerated labor activities (paid cultivation, masonry, carpentry, and housebuilding; see Figure 2). Extra-household social capital is a secondary safety net; and inter-household inter-dependency disseminates out primarily along the axes of biological and fictive kinship (see Figure 3). The role of the household and inter-household relationships are conditioned by opportunities made possible through Haiti’s highly integrated rotating market system (Figure 3). Restricted access to technologies, condition strategies of the household as well as the character of the rotating market. Specifically, simple tools (no more complex than picks, hoes, and machetes), near total absence of effective information systems (extension services and market information), transport systems (roads, trains, and powered shipping), and administrative technologies (regulatory legal systems), the sum of which make the conditions confronting people in rural Haiti resemble, not contemporary conditions for small farmers found elsewhere in the region today, but conditions found in centuries past. These limited technologies and social institutions are aggravated by an unusually harsh and unpredictable natural environment that includes severe storms and frequent drought, and not least of all Haiti’s historic role as rebel black republic among, until recently, officially racist counter nations, something complemented by frequent embargoes, internecine domestic politics subsidized by international special interests, economic and social isolation (for a more detailed historical account of this adaptive process and its implications, read this).