Imported snack foods are another solution to what I have defined elsewhere as the Food Preparation Conundrum (The Storage problem, The Water Problem, The Fuel Problem, The Labor Problem) that has come about with rapid urbanization of the past 50 years. They are inexpensive, ready to eat, available everywhere, have a long shelf-life and are hygienic. But they are a challenge to the industry of local food preparation specialists. They force local food preparation specialists to compete with industrial producers, reducing margins of profit and surely putting many of them out of business (read this post about elite merchant monopoly on bad snack foods). But where prepackaged snack foods are the greatest threat in Haiti is regarding nutritional content.The new industrial practice of manipulating the contents of these foods means that even the milk and cheese available to most Haitians no longer contain the same amount of high-protein dairy products that consumers think they contain. The major brands on the Haitian market contain mostly low-quality substitutes and preservatives that can be found on internet food additive watch lists.

The acceptance of snacks into the popular class food regime and the increasing dependency on low quality prepackaged snack foods such as the pseudo-milk and cheese mentioned above is related to the availability and cost. What Haitians really want—or at least what the vast majority say they want—are organic local foods. But they increasingly cannot get them. The market is currently being driven, not by what Haitians want, but by what can most cheaply and profitably be sold. As one respondent in the research we draw on below articulately explained, “It’s not that we want to eat these foods [prepackaged industrial snack foods]. It’s a question of what’s available.” In this context, a distressing trend is the conceptualization of some foods as nutritious or revitalizing when they are not. Moreover, popular class Haitians are an easy target for unscrupulous manufacturers because they do not read labels on foods, they would not understand the contents if they did, and there is little general knowledge about the content of these foods from elsewhere. Even most upper-class Haitians have no idea that low cost milk and cheese on the popular market is composed of mostly non-dairy products.

Prepackaged Snack Foods in Haiti

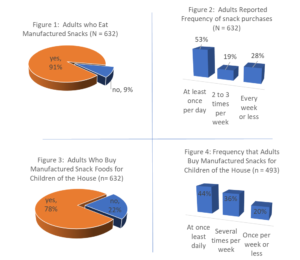

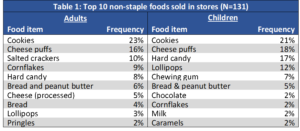

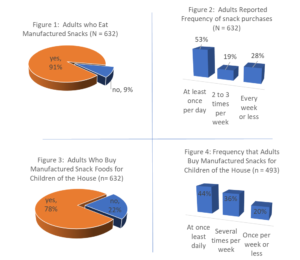

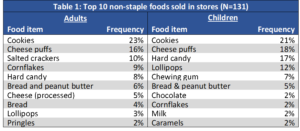

Manufactured snack foods are a recent phenomenon for Haiti.[i] The “snack” food market three decades past was almost entirely artisanal, comprised of those foods discussed here. The prepackaged industrial foods that popular class Haitians in their 30s and 40s and 50s remember from childhood were condensed milk, cheese cubes, and salted crackers. Today is radically different: In a 628 respondent national survey focusing on snack preferences in Haiti, we found that 91% of adults report eating prepackaged cookies, crackers, and cheese puffs (Figure 1), 53% of those people eat them at least once per day (Figure 2); 78% said they buy them for their children (Figure 3), and 44% reported buying such snacks for their children at least once per day (Figure 4). They are purchased far more frequently than other non-staple foods, such as–milk, cheese peanut butter, and bread. In inventory survey of 56 boutik (stores) taken from 50 GPS locations divided between the three urban sites we found that 49% of shop owners report that the number one non-staple food items purchased by adults were cookies, cheese puffs, or salted crackers; in the case of children, 75% of the top sellers were cookies, cheese puffs, hard candy, chewing gum or lollipops (Table 1). It is no secret, even to many impoverished Haitian consumers, that these foods are made of low quality ingredients many of them deliberately stripped of nutrients that the then resold in other forms. Even the cheese cubs and condensed milk that Haitians have come to expect are sources of nutrition have been increasingly supplemented with the low-quality, nutritionally poor ingredients.

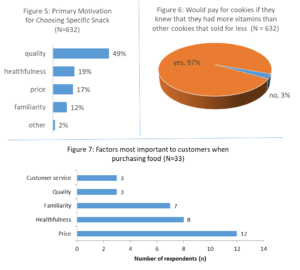

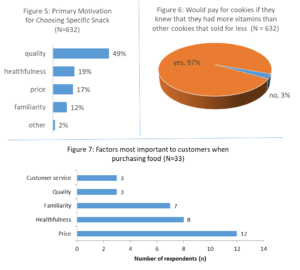

Consumers themselves explained why they most often purchase these “snack foods” as follows. Sixty-eight percent reported selecting specific snack foods for quality or health reasons (Figure 5). And underscoring the apparent interest in nutrition, 97% said they would pay more for a snack food if they knew that it had more nutritive value (Figure 6). But boutik (store) owners were more likely to say the opposite, that consumers were most interested in price (Figure 7).

The low costs of these foods—typically 5 goud (10 US cents) for a pack of cookies, crackers or cheese puffs—and the simple fact that popular class Haitians are economically stressed, might be enough to convince most observers that price is indeed the factor that overwhelmingly determines the incursion of these foods into the Haitian diet.

Cost and the Entrance of Prepackaged Fake Nutritious Foods

Because snack foods are so recent, beyond the fact they have made a dramatic and massive entrance into the Haitian food regime, they offer little insight into the evolution of the market and consumption pattern. Where we can learn more about consumer interest in cost, and the evolution of prepackaged foods on the popular Haitian market is with regard to those that Haitians think are healthy and which have been relied on as ingredients for making protein rich baby foods and the remontan, and fortifying malts and fruit juices: specifically cheese and condensed milk, both products increasingly being substituted with lower cost “fake” products.[i] And here, any doubt about the power of pricing over the quality of ingredients can be put to rest by considering the success of low cost products such as those sold by what is arguably the most successful Haitian food enterprise, Bongu (Deka Group S.A.).

Analysis of Bongu Products

Bongu, like most Haitian corporations, specializes almost entirely in importing and distributing products produced and manufactured outside of Haiti. In the past decade Bongu has taken a major share of markets in spaghetti from Princessa (Bocel Group), salted crackers from Guarina, condensed milk from Carnation, processed cheese from La Vache Qui Rit, protein shakes from Sport Shake, and Corn Flakes from Surfine and Hyde Park. The most obvious way that Bongu has gained market share is by undercutting the competition in cost (see Figure 8).[ii]

Bongu also uses a keen understanding of the preferences of Haitian consumers. Tapping the Haitian interest in local products the company repackages and markets imported products under the nationalist label “Bongu”—Kreyol for “Tastes Good”— and associates its products with Haitian athletes and musicians while touting the moto “Bon pour la sante” (good for the health)—Figures 9 and 10.

How good for the health are the products is hard to say without some investigation. Bongu’s labels do not list how much of each ingredient is in a product. Nor do the labels make clear that substitute ingredients have been added. However, we know that international law requires that ingredients be at least listed by the order of quantity, thus the most abundant ingredient first, second most abundant next, and so on. If Bongu has followed the international law then the primary ingredient in its condensed milk—list first–is “skim milk.” Then comes “soy milk”, then “maltadextrine”–a sweetless sugar used as a thickening agent–then “vegetable fatty matter” and finally “soy lecithin.” The other ingredients are an unknown measure of vitamin A and D and chemical preservatives. In comparison, the main and only food ingredient in the Carnation milk competitor—the one knocked off the market by Bongu–is milk (Figure 11). Bongu cheese lists palm oil as its primary ingredient. Then it lists three milk products: milk proteins, powdered milk, and whey. No cheese. In comparison, the main ingredients in the processed cheese La Vache Qui Rit—also almost completely knocked out of the popular market by Bongu–are “cheddar, Swiss, and semisoft cheese” (Figure 11).

It gets worse, while Carnation and the cheese La Vache Qui Rit brands have–under developed world consumer scrutiny—been very careful to use a minimum of safe additives, If we look at the chemical preservatives, coloring and setting agents in the two Bongu products we find that three of the five artificial ingredients in their milk are listed on internet watch lists as dangerous compounds. All three of those in the condensed milk are on watch lists. [iii] The excerpts below in Figure 12 are cut directly out of the original food additive guides.[iv]

It is not clear whether Bongu is unusual in its use of these ingredients or not. A common belief among merchants in Haiti is that the elite food distributors that have their own brands–of which, at the time of writing, there are only four– have no-compete understandings among themselves. Put bluntly, the rumor is that they collude in an effort to monopolize the market without competing  with one another and driving prices and profits down. While that claim is impossible to verify, there is, prime facie, little overlap in their products. The largest company in Haiti, Gilbert Bigio Group (owned by the Bigio family) has a food subsidiary, Huileries Haitiennes, S.A (HUHSA) that only sells condensed milk, spaghetti, and corn flakes, all products with a wide range of low-cost foreign competitors. But it markets no other products in the Bongu portfolio. Nor do Stanco, Caribbex, and Arlequin, the other three, major corporations with their own brands, have any products that overlap with Bongu. Only Stanco and Arlequin compete directly in the Extruded Corn Snack market.

with one another and driving prices and profits down. While that claim is impossible to verify, there is, prime facie, little overlap in their products. The largest company in Haiti, Gilbert Bigio Group (owned by the Bigio family) has a food subsidiary, Huileries Haitiennes, S.A (HUHSA) that only sells condensed milk, spaghetti, and corn flakes, all products with a wide range of low-cost foreign competitors. But it markets no other products in the Bongu portfolio. Nor do Stanco, Caribbex, and Arlequin, the other three, major corporations with their own brands, have any products that overlap with Bongu. Only Stanco and Arlequin compete directly in the Extruded Corn Snack market.

The one Haitian pre-packaged ready-to-eat-food brand that appears most often as a price competitor with Bongu is the brand Bonlè, which has entered into competition with Bongu, cutting the cheese price even further (33 gde versus Bongu’s 44 gde price for a box of cheese wedges). Bonlè has also entered the condensed milk market as well and it has its own subsidiary brand of Corn Flakes, Anita. But Bonlè is Bongu. It is the same parent company (Cristo S.A.), same products (milks, processed cheese, and corn flakes among them), made and packaged in the same countries (in the case of milk and Cheese, Egypt), with the same low quality ingredients (see above) and the same dangerous colorings and preservatives (ditto).

None of this is to say that Bongu, or rather Cristo S.A. is the sole company marketing low price processed foods with questionable nutritional value, questionable ingredients, and making questionable claims about being healthy. The condensed milk market has at least five imported brands with similarly inferior non-dairy ingredients, most of which laud their high quality ingredients (Figure 15). Other products, such as “Vitamin Cookie Sticks” from China, come with suspicious claims, too (see Figure 16).

But most interesting for the objective of understanding the Haitian market is that even though there are only a handful of Haitian brands and packaging companies, importers of any product that becomes a big seller in the popular market are likely to become a target of Haitian business interests. Two classic examples are Extruded Corn Snacks and Energy Drinks.

Extruded Corn Snacks and Energy Drinks

Extruded corn snacks, particularly what are known as chikos—specifically Chee Co, a brand of the Haitian company Arlequin and suspiciously similar to Cheetos—took over the market from Cheetos with a product that sold for 10 HG, 1/3rd the price of Cheetos. Another Haitian manufacturer Stanco has since replicated the product and captured the market with Chiritos (they also make three other products: Bingo, Crazy Mix, and Anillos). Stanco succeeded by leveraging its distribution and credit networks, incentives to redistributors (50 packs of puffs for every 1000 sold), and, more than anything, by offering and lower priced products: 5 HG. Typical of products discussed earlier, Stanco claims to use “top quality ingredients” and boasts that its products are a “great substitute to those greasy found elsewear” (sic). (see Stanco Website).

Another classic marketing story is the energy drink Toro. The first and the most successful energy drink during the early 2000s was Ciclon, an Austrian beverage distributed through the Dominican company Altacopa S.A. In a textbook case of destroying the competition, the Haitian national bottling company BRANA came up with Toro. Twice the size, with more of the active ingredient Taurine, sold at less than half the price, bottled in a plastic container that resisted damage on Haiti’s dilapidated roads, and advertised in a way that appealed to the Haitian popular conceptualization of energy drinks as enhancing male vitality, Toro knocked Ciclon out of the market in a matter /of months (Figure 18). Seven years later Ciclon is trying to come back by mimicking Toro’s strategy (Figure 19). In the meantime, other companies expanded the energy drink niche with an array of strategies that neatly capture the Haitian conceptualization and marketing predilections of cost, quantity, sexual invigoration, and health. These include Tropic S.A.’s Ragaman, which appealed to progressive minded minority with its allusion to Rasta-man and inclusion of Ginseng as an ingredient, and Tropic’s Robusto, a malt energy drink that capitalized on the association of Malt drinks with nutrition (Figure 20).

In summary, what we can learn from Bongu, Puffed Cereal products and Energy Drinks is that when it comes to modern marketing of manufacturing items,

- a) the proper order of priorities is indeed, price, quantity, and then quality, but

- b) it’s not only about getting calories, hence energy drinks, and

- c) there is a place in Haitian marketing strategies for nutrition and identity, and

- d) poor knowledge of ingredients and the fact that Haitians do not read labels makes them easy prey for suggestive advertising.

Government vs. Merchant Elite: Who Controls of the Market

Government Regulations, Standards and Quality Control

The incursion described above of low quality manufactured ready-to-eat foods and beverages on the Haitian popular market has occurred in the context of weak government and the de facto absence of controls and consumer protection.

Oversight of production and processing of foods and quality control falls under the auspices of the Ministry of Commerce. In Avis CI/0009 dated February 2010, the ministry reaffirmed that,

Alimentary products should be healthy, appropriately packaged and risk free, meaning processed, prepared and conserved in hygienic conditions. They should also be accurately labeled with the following information,

- Name of food type

- List of all the food ingredients by order of decreasing proportion

- Name and address of the manufacturer, conditioner, and distributor

- Date of manufacture

- Date of expiration

- Lot number

In November 2012, with support from EU, MINUSTAH, the German Institution for Standardization, UNIDO, and the government of Brazil, and more $5 million Euros, MIC officially inaugurated the Haitian Bureau of Standards (Bureau Haïtien de Normalisation or BHN). The BHN’s tasks were to devise and implement standards for production and trade in the country, to train inspectors in applying the standards and enforcing compliance with labeling, quality certification, and international product standardization. In addition to governing the local market, the MIC assured the public that “made in Haiti” would “soon be definitely recognized in the international market.” The undertaking was backed up by a new “Metrology Laboratory” where products could be tested for compliance with hygiene safety standards.

There are some problems with the claims. Although the Ministry of Commerce boasts a “brigade of inspectors that strictly applies these laws and punishes non-conformance,” observations on the ground and from interviews with government officials confirms that in 2014-2015,

- BHN, the laboratory, and the Ministry do very little. To quote an official at the Direction de Controle de Qualite des Produits, “so long as a product doesn’t kill someone it can be imported and sold on the local market.” [1]

- Factory samples of locally made products tested are those brought in by the producers themselves, i.e. they can bring whatever they want to be tested as a sample

- Despite the laws: labeling, controls, and inspection are, de facto, non-existent, meaning that respecting the laws above puts manufacturers at a competitive disadvantage relative to non-compliant rivals

- Enforcement is, need we add, non-existent. Nor are there courts and lawyers competent to deal with adjudicating relevant cases

- Neither MARNDR nor MIC were able or willing to provide the consultants with a single document that defines the law (the document cited above and included in Annex 16 came from a secretary acting independently of the Ministry)

- Most of the Haitian government websites are, to put it bluntly, facades with nothing behind them, no data, no downloadable documents. Click a hyperlink or downloadable document and in the vast majority of cases one gets nothing except perhaps a “site under construction.’ Associated service provider sites offer little data as well, other than typically contacts to lawyers or agents with the offer of facilitating access to the market for fees

- MIC staff referred the consultant to the “Director” who knew nothing but recommended a lawyer, saying, ‘he knows’

- According to distributors (see contact list) there are zero controls on patents or use of copyrighted advertisements, for example Spider Man, evident in the “vitamin sticks” from China (see Figure 30 above)

- No inspection labels exist, despite laws mandating them

- When we visited three local peanut producers, having gotten their contact information from jars of peanut butter in supermarkets, we arrived at impoverished households with zero phytosanitary controls. It never occurred to any of them that they could be inspected by a government official

- Imported eggs and breads available in the top Port-au-Prince Supermarkets have no expiration dates

- One distributor/informant interviewed during the course of the research proudly proclaimed that, “Haiti has more laws governing distribution than the US ….” It is difficult to verify whether this is true, since they are neither applied nor published. But the most important point that the businessman was making is that those laws that are applied are there to protect big business—such as his own. There are no active consumer laws. In short, it is a paradise for unethical and locally connected business owners, but a prospective nightmare for consumers who may fall sick from products.

Elite, Imports, Corruption, Political Instability and the Stacked Deck

In the absence of government regulations seen above, any endeavors to import must consider the competitive advantage of those already importing and in control of the customs houses and ports. Figure 32 on the following page uses edible oil imports to illustrate the problems with corruption and favoritism, and elite control of customs houses. Haiti produces no edible oil and, as seen earlier, the population is on the margin of survival regarding edible oil consumption. Biologically, the Haitian population cannot survive with significantly less oil than is imported in the maximum years seen in Section 5. Yet, with the lone exception of the year 2002—more than 2 times higher than the two years around it—we see that the official tally of oil imports fell far below this threshold. This is most likely a reflection of the impact of tax evasion by oil importers that fluctuates with the major political events of the time. For example, changes in recorded imports surrounding the fall of the Aristide government in 2004 have been attributed by some observers to increased imports following the imposition of an aid embargo, and by organized resistance from importers who were being compelled to pay taxes.

In summary, important points that can be drawn from what we know about the importers and distributors of snack foods and beverages are that,

- At least some and perhaps most of the highest tier importers pay little to no taxes (as suggested by the data and according to informants interviewed during the course of the present research), so it is almost impossible to compete with them ( i.e. their profit margins are less than the taxes that a legitimate importer would pay).

- Corruption at the customs houses means that even if they did pay taxes, other importers face significant and often inscrutable and unpredictable obstacles.

- Some elite local processors and packagers may not conform to international standards or laws and instead use inferior products, mislabel, pirate internationally copyrighted packaging, and make false claims regarding nutritional content. They also understand local culture and values meaning they can do all this in such a way as to take maximum advantage in advertising and managing consumer taste and packaging preferences

Summing up these factors, the owner of one of the largest importing agencies in Haiti explained to the consultant, in private, that “these guys could not survive in a competitive market.” The point being that a distributor who tried to conform to international and Haitian laws and standards would be driven out of business by rivals who evaded taxes and otherwise gamed the system.

And finally, if there is a moral to all this, if there has to be a recommendation or a conclusion, it is that the only entity situated to head off what is arguably a nutritional disaster in the making is WFP or UNICEF, either of which could institute a nutritional rating system and proactively make Haitian consumers aware of the nutritional content of pre-packaged snack foods.

NOTES

[1] “depi pwodwi ya pap touye moun yo ka enpote’l jan yo vle sou mache ya”

[i] It should be noted that there are also region differences in time consumption patterns. In Port-au-Prince, peanuts are most commonly eaten in the morning; in Cape Haitian they are most commonly eaten in the afternoon. In explaining these patterns the best place to begin is with patterns of cost, conservative, storage, availability and the market, factors examined in greater detail below. Thus, Cape Haitian is a peanut growing region where Port-au-Prince is not. But peanut butter is in high demand, fetches a high price, is readily stored and shipped. In Gonaives, an area near to the Artibonite, where much local rice is produced, rice and beans is a common morning street food. Both are fresh, and hence easier to cook. But would be thought as peculiar in Port-au-Prince or Cape Haitian where beans and rice are almost exclusively and afternoon meal…

[ii] In the context of the critique made here, it should be mentioned that directors of Bongu have expressed to the consultant regret over the decline in local production and an interest in elevating the nutritional quality of foods on the popular market.

[iii] For E332 and E339 see Cure Zone Guide to Food Additives http://www.curezone.org/foods/enumbers.asp

For E407 See Food Additives Guide (400-495) at http://mbm.net.au/health/

[iv] For E332 and E339 see Cure Zone Guide to Food Additives http://www.curezone.org/foods/enumbers.asp

For E407 See Food Additives Guide (400-495) at http://mbm.net.au/health/

with one another and driving prices and profits down. While that claim is impossible to verify, there is, prime facie, little overlap in their products. The largest company in Haiti, Gilbert Bigio Group (owned by the Bigio family) has a food subsidiary, Huileries Haitiennes, S.A (HUHSA) that only sells condensed milk, spaghetti, and corn flakes, all products with a wide range of low-cost foreign competitors. But it markets no other products in the Bongu portfolio. Nor do Stanco, Caribbex, and Arlequin, the other three, major corporations with their own brands, have any products that overlap with Bongu. Only Stanco and Arlequin compete directly in the Extruded Corn Snack market.

with one another and driving prices and profits down. While that claim is impossible to verify, there is, prime facie, little overlap in their products. The largest company in Haiti, Gilbert Bigio Group (owned by the Bigio family) has a food subsidiary, Huileries Haitiennes, S.A (HUHSA) that only sells condensed milk, spaghetti, and corn flakes, all products with a wide range of low-cost foreign competitors. But it markets no other products in the Bongu portfolio. Nor do Stanco, Caribbex, and Arlequin, the other three, major corporations with their own brands, have any products that overlap with Bongu. Only Stanco and Arlequin compete directly in the Extruded Corn Snack market.