This post is similar to another of my border posts but begins with a more useful summary of the history of the border and examines the re-haitianization of the Dominican side of the border in greater depth, including articulation of both Haitian and Dominican migration and subsistence strategies, and provides some good data. I should date it at 2007.

As in the other post, to briefly qualify my experiences along the border and regarding insights into Haitian-Dominican relations in general: Over the past 25 years I’ve spent 9 years living in the Dominican Republic and 16 years living in Haiti. I have children who were born and grew up on both sides of the island. In my research and travels between 1998 and 2013 I crossed back and forth some one hundred times. I did so variously on foot, bicycle, motorcycle, car, bus, canoe, row boat, and sailboat. Often I crossed in remote areas where there was no official border crossings. I’ve bicycled and motor-biked the entire border once and some segments dozens of times or more. And I have spent months doing research and living in some of the most remote border areas. I’ve been detained on the border five times by various branches of the Dominican police-military apparatuses, put in jail once and another time detained on a Dominican military base for two days. Here’s the first border report I researched and wrote in 1998, something I accomplished with my PhD chair (Gerald Murray) and another then PhD student from the University of Florida (Matthew McPherson). And here’s a 2004 Socio-Economic Assessment for the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve on the border that Mathew McPherson and I researched and wrote. I also have done in-depth research on Lake Azwey on the Haitian side of the border, a report that I am not yet free to post.

History of Border and Re-Haitianization

In the late 1800s and early 1900s about one fourth of the Dominican territory, that closest to the border , was inhabited by more than 100,000 ethnic Haitians and a far lesser number of Dominicans. The Haitian gourd was the prevailing currency, Port-au-Prince the prevailing center of trade and cultural pole, the inhabitants largely Creole speaking or bilingual. Ethnic peace with those in the region identifying themselves as hispanic was the norm.

A change began during the early 1920s when the Dominican government initiated a process of nationalizing the frontier by building agricultural colonies. On October 1937 then Dictator Ralph Leonidos Trujillo led the process to an extreme with the massacre of as many as 35,000 ethnic Haitians in the region. All surviving Haitians were driven out of the region and the border subsequently closed. Creole names for settlements and geographic features were replaced with Spanish names, school teachers were sent into the area to teach nationalist educational programs, and agricultural colonies were built throughout the region. The colonies were populated in some cases with Japanese and Hungarian immigrants as well as Dominicans from elsewhere in the country. As for Haitian migration, it was restricted to a bracero program in which laborers were brought in under military escort to work on state owned sugar plantations far inside Dominican territory (See Baud 1993; Robin et al 1993; Christian Krohn-Hansen 1995; Turits 2002).

With the 1961 assassination of the dictator Trujillo Dominican border polices and anti-Haitianism relaxed, but the character of the border did not immediately change. Government organized colonization of the frontier continued for several decades and for reasons that had as much to do with events in Haiti as the Dominican Republic, it was not until the late 1980s that the character of migration on the border changed. Beginning in 1986 with the fall of the Duvalier regime and a period of ongoing political chaos within Haiti, Haitian Soldiers were often withdrawn from the border and rural areas to deal with problems in Port-au-Prince. In 1994 the border was all but completely abandoned by Haitian authorities when the United Nations occupied Haiti, dissolved the army, and replaced it with a small and weak police force. Since that time economic, ecological, and political crises in Haiti have deepened, the presence of Haitian authorities along the entire 366 kilometers of border has been limited to a handful of agents occupying four border posts. Congruently, the number of Haitians working in the Dominican Republic has skyrocketed.

Since that time the presence of Haitian labor has arguably become the single greatest factor affecting resource use throughout the Dominican Republic. Haitians comprise an estimated 80% of the agricultural labor force, over 80% of that of the construction industry; and as much 80% of the labor force in the tourist industry. Haitians themselves are fond of saying that the Dominican Republic is being ‘built on their backs’ and the observation is difficult to refute. The approximately one million mostly young male Haitians keep wages in the DR low and help make the DR the world’s fourth-largest US offshore assembly sector and the number one Caribbean destination for low-budget US and Western European tourists (PNUD 2006; Banco Central 2006).

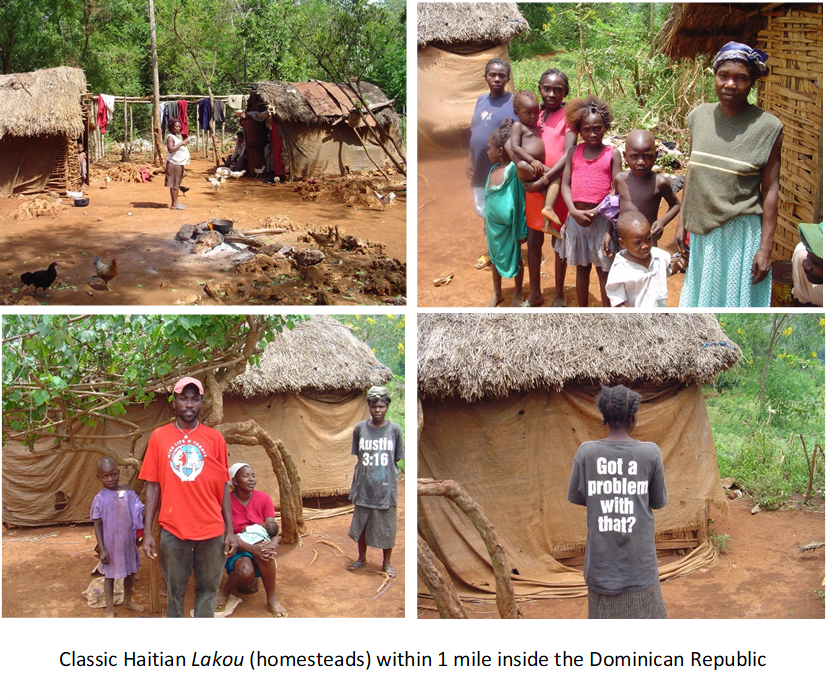

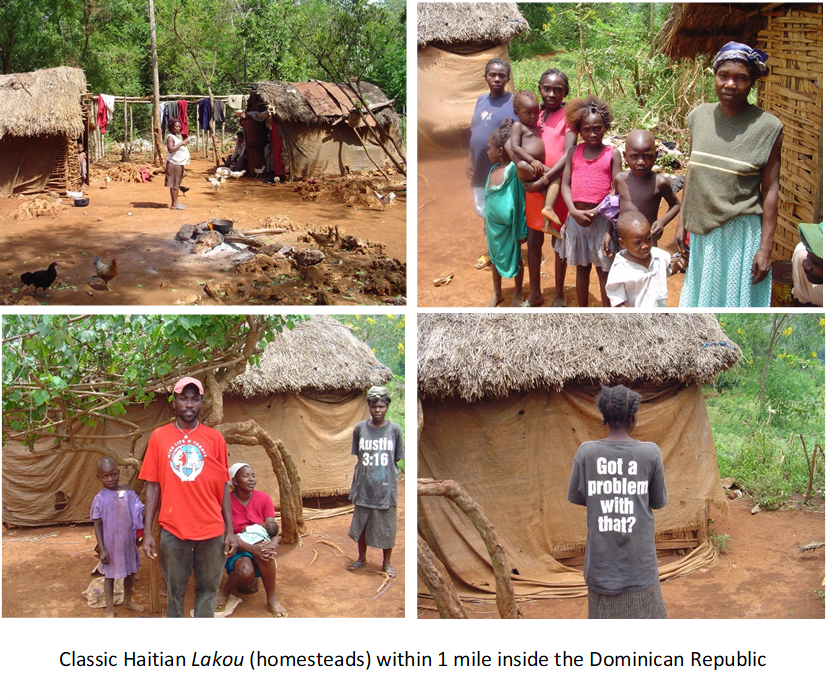

As a result, the character of the border has also changed. This change is not as simple as Haitian immigration. Over the same period that Haitians have been coming crossing over to the Dominican side of the border to escape misery and poverty in Haiti, rural Dominicans have increasingly found life in the area intolerable and they profit from the immigration of Haitians to underwrite their own out-migration. Haitians were, and increasingly continue to be taken on as caretakers in what is often a serf-type of relationship where the Dominican retains ownership and control over all the products of the farm. In other instances, the male Dominican household head stays at least part-time on the farm. He takes on a Haitian common-law wife, often brings her children over, and bears more children with her giving way to a bi-national family that creates kinship links and claims of nationality on both sides of the border. While Haitians are usually quick to adopt Dominican language, dress and culture, the rapidity of the migration has meant that some areas have been almost completely Creolized, not unlike what must have existed prior to the 1937 massacre. The voyager who steps out of the pueblos and penetrates into the more remote countryside finds in many areas soccer fields, characteristic of Haiti, rather than the baseball diamonds found in most of the Dominican Republic; Haitian boutique for stores instead of Dominican colmados; homesteads in the form of the classic Haitian lakou with joupa or kay pay instead of Dominican patios with a casucha, and small thatch Haitian churches instead of Dominican chapels.

To illustrate the degree of Haitian incursion that has occurred in many areas, the most recent government vaccination drive in one sección turned up a total of 700 families both in the colony and in the surrounding agricultural areas. In the colony there were 135 homes occupied in the following manner: 25 were empty houses, the owners having gone to live in the nearby county seat or to the city; 75 were inhabited by purely Dominican families; 20 of the homes were inhabited by purely Haitian families; and 15 were inhabited by Dominican men in union with Haitian women. Outside the colonia, among the agricultural plots and coffee plantations, there were 565 households, of these, four were Dominican men in union with Haitian women and all the remaining 561 families were Haitian. Similar trends were evident in other colonies in the region.

One aspect of the Dominican-Haitian migration relationship has been the impact of this migration on the natural landscape. Haitians are often accused in the national press of preying on the Dominican environment by cutting trees for charcoal production and export to Haiti and clearing land for gardens. This occurs, but Haitians are not doing it indiscriminately. On the contrary, the overwhelming pattern is that Dominicans pay Haitians to cut wood for charcoal and they enter into agro-industrial ventures with Haitian workers such as bean and cabbage production for the market. Most importantly they broker access to land for conucos (swidden plots). In some cases this is done for profit through sharecropping agreements ranging in configuration from a medias (halves), a tercios (thirds), to a quintas (fifths). Under these arrangements the Dominican national typically provides the capital for seeds and any chemical fertilizers or pesticides needed. The sharecropper provides the labor. Upon harvest, the Dominican who invested capital recuperates his or her investment and the remainder is split according to the agreed-upon portion of the harvest.

Even more common is the use of Haitians to transform the landscape in ways that appear to be largely undetected by the authorities. Specifically, semi-resident Dominicans, many who have already moved to town or the capital and a minority of whom are powerful landowners, give Haitians access to forested land to plant conucos. On the surface this appears to be an intensification of crop production. But most Dominicans grant conuco land not with the expectation of receiving part of the harvest but with the expectation that the Haitian tenant will, after the cycle of harvests characteristic of local swidden farming, plant grass and abandon the garden, thus converting the forest cover to pasture for the Dominican farmers’ preferred, more lucrative, and less labor-demanding enterprise of cattle-raising.

While doing research on the border for UNESCO in 2004, virtually every Haitian I interviewed on the topic—over 117– reported that Dominicans cede garden land to them for a specified period of time under the condition that they plant grass. The Haitian clears the land, plants a swidden garden, and within one to two years must abandon the garden, plant grass and turn the land back over to the Dominican owner (the type of grass is guinea–Paricum maximum–at lower, drier altitudes and pangola–Digitaria decimbens–at higher more humid altitudes). In the meantime the temporary Haitian residents are paid to cut posts and stringing wire for absentee or part-time Dominican ranchers who would prefer to live in the city.[iv]

The consequences of this ‘savana-ization’ are massive as evidenced by the rapid deforestation of the hills surrounding the major coffee growing area in the region, something began during the late 1980s at precisely the time when large numbers of Haitians first began entering the coffee labor force, i.e. when they became available to work swidden gardens (see SEA/DVS 1994).

Conclusion

In concluding, the process described shows how migration of one population is part of a migratory and economic process of another. In this case, the immigration of Haitians has articulated with the out-migration of Dominicans and the associated economic and environmental transformations–the transformation of the economic activities from farm to ranch and the transformation of the rural landscape from dry forest to pasture. A process that is undermining conservation in the Jaragua-Bahoruco-Enriquillo Biosphere and may eventually entirely destroy the dry forest in the reserve.

The process has a definite pattern for the participants and the outcome for the environment and regional economy can be anticipated. To begin with, it is only areas where there are high labor needs that one finds large numbers of Haitians. The fact leaps out at the traveler. In ranching areas one may voyage for miles without seeing anyone or spotting inhabited homestead. In agricultural areas one sees both Dominicans and Haitians riding mules and donkeys, walking, and working in the fields, the land dotted with both Dominican and Haitian homesteads. But by participating in the transformation from farm to ranch and hence from high labor demands to low demand, Haitian laborers sow the seeds for their own regional obsolescence. As the area is transformed from one of both agriculture and livestock rearing to one predominantly of cattle grazing, labor needs decline, and hence fewer job opportunities remain. Without jobs or access to garden plots, Haitians move on to towns and cities.

As for the Dominicans involved in the process, although it was presented above as a process of small Dominican farmers, it is not just poorer Dominicans sponsoring the savanization of the area. Involved are wealthy urban based landowners and part time ranchers who live in the Dominican capital, Santo Domingo, as well as multinational investors. Moreover, the process seems to favor those who have the wealth to buy and fence greater areas. It appears that small farmers reach a point where they are disposed to sell their land, cut all ties to the land and remain with their families in the cities and pueblos.

The determinant factor in the process described above is the beef market. The removal of US taxes on Dominican beef that will come about with the CAFTA (the regional free trade agreement with the United State) suggests that the environmental future of the south western Dominican Republic, two thirds of which is a new United Nations Biosphere Reserve, is bleak.

NOTES

The information for this post was collected during a 2004 research project for UNESCO. On November 6th 2002, UNESCO declared 4,858 square kilometers of the southwestern Dominican Republic (10% of Dominican national territory) the world’s 412th Biosphere Reserve. The reserve, called the Jaragua-Bahoruco-Enriquillo (JBE) Biosphere Reserve, includes vast areas of sensitive dry forest, the Caribbean’s largest inland lake, the largest population of American Saltwater Crocodiles in the world, and some of the most undisturbed marine resources in the Caribbean basin. The reserve also includes 120 kilometers of border with neighboring Haiti. The research below, originally conducted in association with the development of a management plan for the JBE Biosphere Reserve, shows how in-migration of Haitians has articulated with out-migration of Dominicans in such a way as to change the agriculture and livestock rearing practices, culture, and the environment.

For other works on the Border and/or Dominican Haitian relations, see these posts:

TRAVESTY OF THE HAITI VS. DOMINICAN MANGO INDUSTRY

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: THE HAITIAN-DOMINICAN BORDER: MISUNDERSTANDINGS

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: WHERE DID ALL THE GIRLS GO? RURAL DOMINICAN SEX RATIOS

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: JUSTICE SYSTEM IN THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: AN OPEN CRITIQUE OF JARED DIAMOND’S COLLAPSE (HAITI AND DR)

WORKS CITED

Banco Central de la Republica Dominicana.

Mercado de Trabajo 2006. Santo Domingo, D.N., República Dominicana.

Baud, Michiel 1993 “Una Frontera Pare Cruzar: La Sociedad Rural; a Traves de la Frontera Dominico-Haitiana (1870 !930)” In Estudios Sociales Ano XXVI, Numero 94: 5-28 Octubre-Deciembre.Trans Eugenio Rivas

Christian Krohn-Hansen 1995, “Magic, Money and Alterity among Dominicans”, Social Anthropology, 3(2):129–46

PNUD 2006. Desarrollo Humano en la República Dominicana 2000. Editora Corripio, Santo Domingo, República Dominicana.

Robin, L.H., and Derby Turits, Richard Turits 1993 “Historias de Terror y los Terrores de la Historia: La Masacre Haitiana de 1937 en la Republica Dominicana” In Estudios Sociales Ano XXVI, Numero 92: 65-76 April-June.

Turits, Richard Lee “A World Destroyed, A Nation Imposed: The 1937 Haitian Massacre in the Dominican Republic” Hispanic American Historical Review – 82:3, August 2002, pp. 589-635

NOTES

[i] The DR and Haiti have a long history of migration, mostly from the Haitian or former French side to that of the Spanish or more recently the Dominican side. It is not always clear in the historical literature how welcome Haitians were. During much of the colonal epoch that the Spanish colonial government welcomed fleeing slaves. White colonists fleeing the subsequent slave insurrection and revolution were also welcomed.

[ii] Through the ‘a medias’ (halves) arrangement the Dominican owner of the land provides the capital needed to purchase seeds, fertilizers and other inputs. The sharecropper provides the labor. The sharecropper also either resides in simple shack (jumpa or ranchito) built in the field or may reside in and serve caretaker of the landowners homestead. Once the harvest is sold, the owner first recuperates his capital investment. Then the remaining profits are split 50/50. This arrangement predominates in the highland farming communities surrounding Parque Nacional Sierra de Bahoruco, particularly along the border. On the other hand in the ‘a quintas’ (fifths) arrangement, the landowner cedes the property over to a sharecropper, who farms the land making all necessary investments in capital and labor. The owner receives as payment one fifth of the total harvest.

[iii] In areas close to the border this is done on a sharecropping basis, the owner of the land taking 1/5th to ½ of the yield. As one moves away from the border, where Haitian labor is readily available, the demand for a share of conuco yields disappears and Dominican farmers give Haitians conucos for nothing. In this way granting Haitians access to garden plots appears to be an attempt to increase or at least maintain income, secondarily to fill the labor vacuum created by Dominican out migration, and perhaps to keep Haitians readily available for day labor.

[iv] Thus land owners in the region appear to be using an age-old strategy of eluding conservation policies by transforming protected forests into unprotected grasslands. Pasture is often preferable because absentee land owners can graze cattle, a profitable enterprise that does not demand large inputs of labor (see McPherson 2003 for description of similar practices in the Cordillera Central).