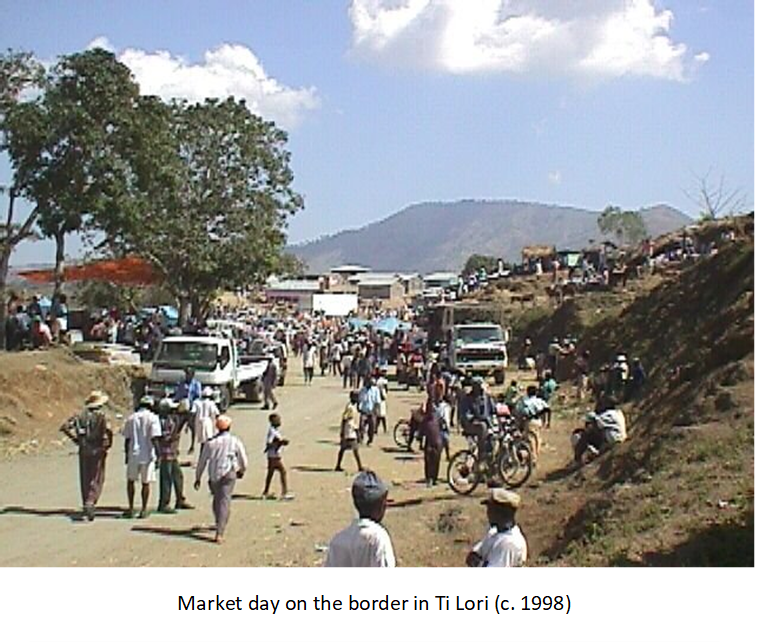

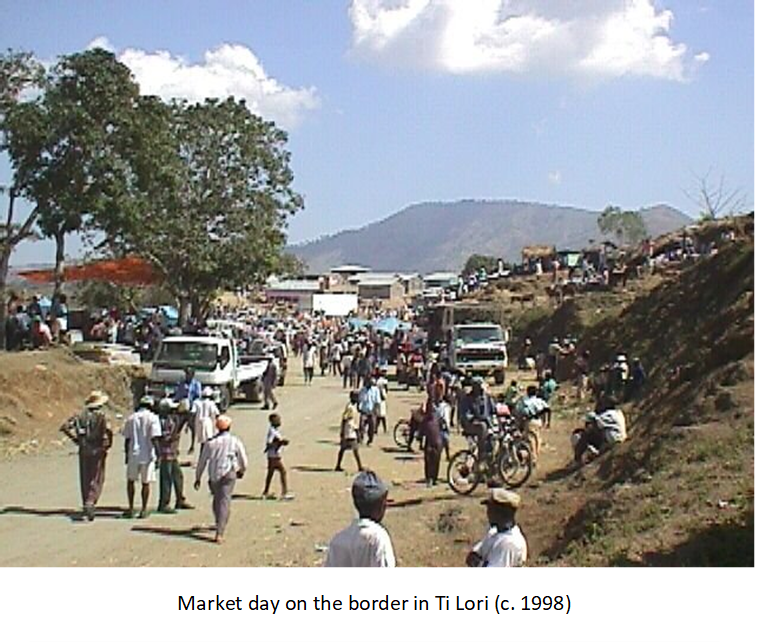

The Haitian-Dominican border is a widely misunderstood place. Here I want to share some insights in hopes that they will contribute to a better understanding of the area. But before I get started, I want qualify myself as not just another anthropologist whining about Dominican-Haitian relations. Over the past 25 years I’ve spent 9 years living in the Dominican Republic and 16 years living in Haiti. I have children who were born and grew up on both sides of the border. Between 1998 and 2013, in my research and travels, I crossed the border perhaps one hundred times or more. I did so variously on foot, bicycle, motorcycle, car, bus, canoe, row boat, and sailboat. Often I crossed in remote areas where there was no official border crossings. I’ve bicycled and motor-biked the entire border once and some segments dozens of times. And I have spent months doing research and living in some of the most remote border areas. I’ve been detained on the border five times by various branches of the Dominican police-military apparatuses, put in jail once and another time detained on a Dominican military base for two days. In 1998 I was co-author of a major USAID funded border study, something I accomplished with my PhD chair (Gerald Murray) and another then PhD student from the University of Florida (Matthew McPherson). In 2004 I was co-author of the Socio-Economic Assessment for the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve on the Dominican side of the border, something I accomplished with my colleague Mathew McPherson of NOAA. I also have done in-depth research on Lake Azwey on the Haitian side of the border, a report that I am not yet free to post.

Haitian-Dominican Border

The political, military, and economic hegemony of Dominicans means that they have an advantage in treating with their Haitian neighbors. Along the entire 366 kilometers of the border, the Haitian police are present at only five posts; in contrast, the Dominican military has a guard post and watchtower every ten kilometers. The Dominican Republic annually exports $350 million worth of building materials and eggs to Haiti ; in return, Haiti exports only $3 million worth of goods to the Dominican Republic. Haitians sometimes suffer as a consequence of the Dominican advantage. The drastic differences in wealth, services, and police-military power give way to discrimination and abuses.

However, border relations run deep, they cut across family lines, they circumvent laws and, although they are sometimes fraught with national pride and racial prejudice, economic inter dependency among those who live on the border takes precedence over tensions. The border is porous to everyone but the authorities and tourists.

The characteristics described above give way to the type of direct abuses—enslavement, robberies, rapes, kidnapping and murders–that sensationalists and charity seekers like to dedicate themselves to advocating against and that stir the ire of the compassionate readers. In my experience, most of these people who make these claims know little to nothing about the area and are unlikely to ever taken the time to verify their claims. Nevertheless, some if not many of the abuses indeed occur. But what I want to focus on here is that the power differentials along the border also give rise to special type of abuses and exploitation, one in which laws are circumvented and the environment suffers. The points are made clearer in the short discussion that follows. But suffice it to say here that while at first it may not appear so, this is not another lament of the abuses heaped on Haitians by Dominicans. First the direct abuses.

Direct Abuses

In search of work, Haitians migrate in great numbers to the Dominican Republic. Credible estimates put the Haitian population in the Dominican Republic at over 800,000, almost ten percent of the total Dominincan population. Overwhelmingly impoverished, rural, and semi-literate, the majority of these individuals are disadvantaged and suffer discrimination even before they cross the border; in the Dominican Republic matters are worse. Most Haitian immigrants do not speak fluent Spanish, have no legal entry papers, are less educated than Dominicans, are conspicuously darker, and dress conspicously differently. At the hands of their Dominican hosts they commonly suffer ridicule and abuse. They are spoken to disrespectfully, they must pay bribes to corrupt migration officials, and they are sometimes caught up in mass repatriation drives and sent home without having an opportunity to collect pay or personal belongings, at times leaving spouses and children behind. In the border area these abuses are intensified.

Dominican military commanders working on the border sometimes round up hapless Haitians and put them to work on their farms. Haitian children are often lent to Dominican families in a type of domestic servitude that some have likened to slavery. Otherwise law-abiding and hardworking Dominican campesinos who take it as their due to habitually rob Haitians who surreptitiously cross the border, detaining them at gunpoint and with dogs, searching them, and taking whatever cash, cell phones, or other goods they possess (I am not repeating hearsay, I’ve been present; everyone seems to see it as natural course of events).

More extreme examples include cases of murder and rape that go without ever being investigated. I once interviewed Padre Ruquoy (2004), a rather famous activist priest who the Dominican government eventually deported. Ruquoy lived and ministered to Haitian laborers working on a sugar plantation near the Dominican mountain community of Polo, the first place that Haitian migrant laborers arrive after trekking through the Sierra Bohoruco Park on their trip to work in the DR . In 2004 he gathered reports of a massacre of 25 Haitians in the Sierra de Bahoruco, an incident that I also heard of from Dominicans living in the Mountains. Ruquoy also investigated and viewed the corpse of a Haitian man he claimed had been raped and killed in the same area. In 2009, I was in the border town of Jimani when 8 Haitians were massacred nearby. They had been making charcoal under the auspices of a Dominican Patron in a place called Boca Cochon when they were surprised by gunmen. Eight were killed, their bodies then pitched into the smoldering charcoal. I was there at the hospital three days later when two boxes swarming with flies were brought in; their contents, corpses of two of the men. At least five other men had escaped to recount what happened to Haitian police. Everyone in the area, Dominican and Haitian alike, were outraged. Charcoal production, albeit illegal, is a major industry in the area, even on the Dominican side of the border where it is conducted under the auspices of the Dominican Military. It was inconceivable that someone local would have done it or could have gotten away with such a crime. One irresistible hypothesis was that the men were killed by Dominican special forces unfamiliar with the border. Then Dominican President Leonel Fernandez was scheduled to make a highly publicized visit to Jimani the very next day, the first time in four years a Dominican President had visited the border. In preparation, Dominican special forces had been flying over the area all day in helicopters. Once again, the men were almost certainly victims, not of Dominicans living in the border area, but misunderstandings among those who only know Haitian-Dominican border relations only through heavily biased News media accounts of Haitian environmental depredation and patriotic Dominican resistance.

International cooperation along the border

Despite the preceding, any study of Haitian-Dominican relations must not overstate abuse, particularly regarding those who live along the border. People of both countries who live along the border are locked in a mutually beneficial trade, relations of production and even blood. The institutions that appear exploitative to outsiders sometimes render substantial benefits to the apparent ‘victims.’ A few examples: Haitians farmers who appear to be in a type of peon relationship with their Dominican ‘patwon’ are able to access fallow land on the Dominican side of the border through their relations with Dominican farmers. In joint ventures Dominican agro-entrepreneurs also advance tools, seeds, pesticides and chemical fertilizers to Haitian farmers. In the cross border child domestic servitude mentioned above, an institution called restavek in Haiti (Haitian children are loaned to better off families in exchange for education), there is ample reason to believe that, on the whole, Haitian children are treated better and find greater advantages on the Dominican side of the border than they do back home (an astounding number of Haitian children take it upon themselves to leave home at ages as young as seven years old—see The Fading Frontier 1998). As for Dominican legal authorities abuse of Haitians: it happens. Dominican police and military are renown for abusing their own people as well. However, in a more positive light, we have found that Haitian emigrants usually report satisfactory recourse to police and military adjudication in labor disputes, regardless of whether or not the individual has legal entry papers. Moreover, Haitians are not completely powerless in the face of repatriation drives. Angry Haitians have on occasion retaliated on their side of the border with roadblocks, closing the border and shutting down trade with the Dominican Republic. The result is trade backlogs, spoiled produce, and a clear demonstration to Dominican producers and politicians of the importance of maintaining open access to the Haitian market, i.e. trying to limit abuse.

None of this is to say that there are not abuses along the border. As I described earlier, there are abuses. In some cases these abuses are extreme, such as the robbing and occasional killings mentioned. But the imbalance in power must be understood in the reality of life along the border. The relatively better off Dominicans have come to depend on their Haitian counterparts and the politically and economically weaker Haitians have adopted behaviors that work to their material advantage. Moreover, there are cross-border relations of production that go beyond national, class, and racial prejudices.

Border Culture

Intermarriage between Haitians and Dominicans is common among people living along the border, particularly Dominican men seeking union with Haitian women. There are cases of genuinely affectionate adoption of Haitian children by Dominican families and I could cite dozens of cases where Haitian children who otherwise would not have had educational opportunities began as restavek in the Dominican Republic, subsequently finished high school, went to Dominican Universities, and became professionals. There is an impressive level of bilingualism, particularly in the southern part of the border area. In most areas it is Haitians who speak Spanish, but in areas, such as Macasia, where Haitians enjoy greater wealth, Dominicans speak Kreyol and Haitians are monolingual. Dominican clinics and hospital administrators consistently report 30 to 40% of child births in border clinics are to Haitian mothers. Dominicans commonly seek out Haitian spiritual healers when ill– and Haitian sorcerers when angry. Haitians often boast about their Dominican patwon while Dominicans along the border report relatively few conflicts with their Haitian neighbors, admit their dependence on Haitians as workers, and express a guarded respect for their counterparts on the “other side.” These positive relations are particularly common with Haitians living directly on the border. Haitians who come from farther away, are more often victims of verbal or physical abuse or other types of mistreatment in the Dominican Republic.

International Cooperation Circumventing Laws

The configurations of cooperative relations described above give way to a different type of abuse, one that has received less attention. It is not confined to one nationality and it goes beyond the level of individual. It is made possible by the presence of a border with the specific and unique characteristics mentioned earlier—porosity, extreme poverty, and an unguarded side. The most obvious form of this abuse is the organized gangs of Dominican and Haitian livestock thieves who steal livestock on one side and then smuggle it to the other; as well as the smuggling in drugs, wildlife, and arms. But I am also referring to the less obvious but anthropologically fascinating processes that undermine conservation efforts along the border and invite radical and potentially violent backlashes from urban centers of political power (in this case, Santo Domingo). Three cases in point,

Dominicans agro-entrepreneurs who finance and provide access to pesticides, fertilizers, tools, and seed, play a positive role for the Haitian agro-entrepreneur but, given the absence of authority on the Haitian side, underwrite the destruction of Haiti’s principal national park, the Pine Forest (see Biosphere Reserve 2005).

On the Dominican side of the border Haitians are used to circumvent Dominican conservation laws and convert dry forest to pasture land. The process works as follows: the Dominican farmer brokers Haitians access to State land. The Haitians cut the dry forest and plant a conuco/jadin, thus gaining income and protected access to the Dominican market. The catch is that the Haitians must abandon the land within six months to a year and plant guinea grass, thus turning the land into pasturage. In this way the Dominican farmer is able to eradicate the protected forest to make it hospitable for his preferred means of income, cattle grazing, while being freed of reprisal from park authorities—he blames it on the Haitians (see Biosphere Reserve 2005).

Haitian caretakers and their families are used to underwrite Dominican migration out of the region. The process works as follows: the Dominican farm owner invites a Haitian family to be caretakers on his farms, thus begining the immigration process for the Haitians. The Dominican hosts use the produce from the farm to underwrite his family’s own migration to the nearest pueblo and then Santo Domingo or overseas (see Biosphere Reserve 2005). In some areas, such as the Pedernales/Agua Negro area, this process has resulted in a complete re-Haitianization of the Dominican side of the border (we say ‘rehaitianization’ because prior to the 1937 massacre, Haitian cultural patterns prevailed deep into the Dominican Republic)

Whoever reads this, I hope that when thinking, studying or writing of the Haitian Dominican Border they will not limit themselves to the flagrant examples of human rights violations common wherever one encounters extremely impoverished and relatively powerless people confronted with people of greater wealth, authority, and military might. I encourage the researchers to document the abuses, but I also hope that aid workers and scholars who work on the Haitian Dominican border will begin to promote international cooperation rather than agitate a situation that in the past has been made volatile, not so much by the people who live along the border, but by those who live far from it.

For other works on the Border and/or Dominican Haitian relations, see these posts:

TRAVESTY OF THE HAITI VS. DOMINICAN MANGO INDUSTRY

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: WHERE DID ALL THE GIRLS GO? RURAL DOMINICAN SEX RATIOS

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: JUSTICE SYSTEM IN THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: AN OPEN CRITIQUE OF JARED DIAMOND’S COLLAPSE (HAITI AND DR)

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: HISTORY OF BORDER AND RE-HAITIANIZATION

Works Cited

Murray, Gerald, Matthew McPherson, and Timothy T. Schwartz. 1998. Fading frontier: An anthropological analysis of social and economic relations on the Dominican and Haitian Border. Report for USAID (Dom Repub).

McPherson, Matthew and Timothy Schwartz, 2004, Socioeconomic Assessment of the Jaragua, Bahoruco. International Resources Group/IPEP and Enriquillo Biosphere Reserve McPherson and Schwartz