A closer look at evidence and trends in the market suggests that the local market for mangos is better than that of the export market. It offers producers more money. Indeed, to get mangos from producers, the exporters, their voltije and fourniseur agents have to resort to trickery and financial advances on trees 9 months before the harvest. Consider the following:

- A vigorous local market is evident in Les Cayes region in the south where ASPVEFS, a cooperative originally created to support Francique production for the export sector has come to trade most in non-Francique mangos, especially Blan and Zilot mango. They sell to local female traders for 50 HTG per dozen, a price comparable to packing house prices for Francique. Market women turn them over in small lots of 2 to 5 mangos at a profit margin as high as 100%.

- The situation is such that the Les Cayes region has over the course of the Haiti Hope project ceased to supply mangos to the Port-au-Prince exporters. One explanation offered is that this as a consequence of reduced harvests, changes in climatic patterns brought about by global warming (Finnigan 2015 personal communication). But in the period 1985 to 2011 ORE received over US$10 million for tree grafting and maintenance programs, with Francique Mangos as central focus of all the those projects.[1] ORE and the South Mango producers are currently benefitting from part of a 20 year $200 million sustainable development initiative for 10 Communes in the southwest of Haiti. With this in mind, there should have been a surfeit of mangos in the south. And there may well be. But there is also good reason to believe that those mangos are staying in the Sought because significantly greater price than offered in the export market chain. In 2010 CRS reported the price of Francique mangos in the ASPVEFS cooperative near Les Cayes at 20 HTG per dozen (or USD $0.50). In 2015, the cooperative was paying 25 HTG, (50 cents). Voltije were paying 25 to 30 HTG. As seen, neither of them were sending mangos to Port-au-Prince, where they would have sold to JMB or Ralph Perry Packing House for 40 to 42 gourdes per dozen of 13 mangos. Instead they were selling them to local traders at 50 HTG per dozen.

- We also know anecdotally from exporters that competition from the local market is a major challenge. As seen earlier, to be successful fournisseur speculate months in advance harvests by purchasing trees at below market prices. One exporter reported that he distributes US$100,000 to fournisseur in the month of September, six months before the onset of the export season. The exporter explained this as helping the peasants get the money to pay for their children’s school. But the advantage to the exporter and fournisseur is that, once again, they get the mangos at a significantly reduced price. One suggestion is that without buying trees at 50% discount before harvests, exporters may not get enough mangos for their market. The implication is that one reason for the incapacity of exports not to meet demand is in fact high prices on the local market.[ii]

- Even non-export quality mangos sell on the local market, some at competitive and even higher prices than Francique. Rosalie in Cape Haiti

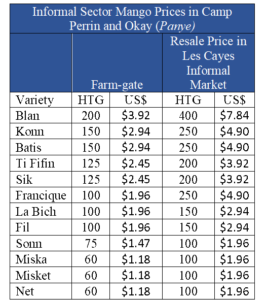

are a small, easily bruised mango with a large pit. Yet they sell at the farm gate for 150 HTG (US$2.95) per Panye (600 HTG per makout; see Table 3.3).[2] They have significant enough retail value on the Haitian domestic market for traders to ship from Cape Haitian to Port-au-Prince. The Batis mango is even more highly prized in Cape Haitian, selling for an average of 175 HTG (US$3.43) per ~60 lb Panye (700 HTG per makout). To put these prices in perspective, one Panye can hold five dozen Francique mangos (14 fruits per dozen) that sell farm-gate on the export market chain for 36 HTG per dozen. If we calculate what the export market price in terms of Panye, this translates to 180 HTG per Panye of export quality Francique mangos. Comparing volume for volume (measured in Panye) this farm-gate export market price for the very best Francique with the farm-gate prices for Batis Mangos in Cape Haitian: the values are identical. Similarly, data gather for Les Cayes, indicate that local market Francique prices exceed the 180 HTG per Panye by 70 HTG but that Francique are only mid-range in value when compared to other varieties (Tablet 3.2).

are a small, easily bruised mango with a large pit. Yet they sell at the farm gate for 150 HTG (US$2.95) per Panye (600 HTG per makout; see Table 3.3).[2] They have significant enough retail value on the Haitian domestic market for traders to ship from Cape Haitian to Port-au-Prince. The Batis mango is even more highly prized in Cape Haitian, selling for an average of 175 HTG (US$3.43) per ~60 lb Panye (700 HTG per makout). To put these prices in perspective, one Panye can hold five dozen Francique mangos (14 fruits per dozen) that sell farm-gate on the export market chain for 36 HTG per dozen. If we calculate what the export market price in terms of Panye, this translates to 180 HTG per Panye of export quality Francique mangos. Comparing volume for volume (measured in Panye) this farm-gate export market price for the very best Francique with the farm-gate prices for Batis Mangos in Cape Haitian: the values are identical. Similarly, data gather for Les Cayes, indicate that local market Francique prices exceed the 180 HTG per Panye by 70 HTG but that Francique are only mid-range in value when compared to other varieties (Tablet 3.2).

Whatever the real prices were in the past, mangos are today a commodity, one that has entered vigorously into the local market system and, as evidenced by the informal vs. export market chain prices differentials seen in the previous section may have done so on a level comparable or greater than that offered in the export market. This point is somewhat surprising given that that development reports consistently rate domestic prices far below the mango export value chain. Yet, as Oxfam (2014) and TechnoServe (2010) recognized, there is a vigorous local market. The prices paid by fournisseur for export quality mangos appear to be exceeded by those that local market traders pay to producers for mangos destined for the local market. This may explain why fournisseur rent trees for 5-year stints and buy trees as long as 9 months before the harvest, i.e. it is the only way they can get enough mangos and at a price that would yield profits. This would also explain the powerful impact of credit on availability of mangos. Indeed, the Haiti Hope credit program empowered producers to holdout, not just against the fournisseur, but also against the TechnoServ cells themselves, thereby explaining why the defection rate of Haiti Hope TechnoServ sellers from one year to the next varied as high as 60 percent.[iii]

(for references and more data see here)

Notes

[1] Funds and support came EU. CRS-MYAP, USAID, VSF-CICDA/STABEX. ICCO, UCG/IDB, USAID HGRP – PADF/USAID FAO, MARNDR.

[2] Makout is a two pocket saddle bag woven from green royal palm fronds. One full makout (both pockets), holds 4 panye

[i] A point in elaborating on the fact that Part of the confusion over market prices is an apparent expectation on the part of international stakeholders mangos sold on the domestic market are selling for prices far below export prices or rotting on the ground (admittedly, the consultant thought the same). For example, in 2010, Haiti Hope estimated export quality mangos at 26 HTG ($0.51) and local quality at 14 HTG ($0.20), less than half that price, In 2015 they made a similar claim, reporting that non-PBG producers were receiving 20 HTG ($0.39) per “dozen” for Francique mangos vs. the PBG price to growers of 42 HTG ($0.82). Yet three years earlier, in 2012, Lidwine reported that in the same area producers were selling at the farm gate and to local-market reseller at 26 HTG per dozen. One more step down the value chain “rural retailers will purchase domestic quality mangos in bulk at $1.25 per dozen of from 14 to 20 mangos,” which is considerably more than the packing houses were paying in 2015 (Hyppolite 2012).