Here I provide a brief summary of the cultural materialist model with the graphic Cake of Culture. I do so because, a) The model is useful to those seeking to understand the social system in developing countries, and more specifically for those endeavoring to evaluate development interventions and understand why they work or don’t work the way anticipated, and b) with the exception of another of my own posts (see for example MEVMS), I can’t find a similar summary online.

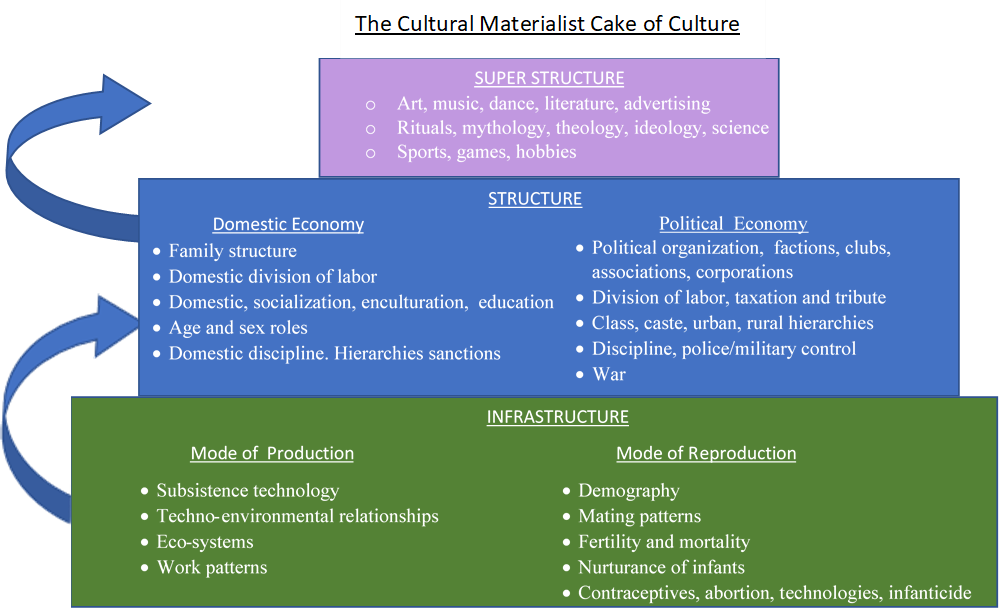

For those not familiar with the model, The ‘cake of culture’ model builds on the work of Carl Marx, Leslie White, and one of my own former professors, Marvin Harris. It organizes culture into three layers, Infrastructure, Structure and Superstructure.

1) Infrastructure: the concrete material base

- natural infrastructure: environment: sea, forests, rivers, savannah, mines, foliage, fishing grounds

- human infrastructure: demography, roads, transport, communication systems, material and strategic technologies

2) Structure: humanmade institutions such as government, religious institutions and organizations, military, police, schools, markets, stores, cooperatives, clubs, associations, NGOs …

3) Superstructure: Ideas, religions, taboos, celebrations

What makes the use of the ‘cake of culture’ powerful and useful to development practitioners is the concept of ‘infrastructural determinism’ or what is also summed up as ‘the primacy of the infrastructure’: the assumption that the direction of causation moves primarily from infrastructure to structure to superstructure.

This emphatically does not mean that superstructure—ideas and beliefs—are not important and cannot play a decisive role in development. The point is that these ideas and beliefs and how to change or influence them must be understood within the constraints of the environment and existing social institutions. In some respects, this is a painfully obvious point: it makes no sense to teach the Dinka in Sudan how to make and improved igloo. A more nuanced example is that it makes no sense to try to pass and enforce conservation laws in a society that has no police or rangers to enforce them nor if the government structure, the will, and/or finances to support such specialists does not exist. As for ideology, such as religion: obviously ideology can have a very real impact on options for development interventions. For example, aid practitioners would almost certainly be wasting their time and even endangering the lives of women and girls if they did not take ideology and religion into consideration when trying to encourage rural Afghan women to start their small businesses. The reason being, of course, is that Islamic custom in rural Afghanistan calls for the punishment of women who pursue economic independence of their husband or male relatives. So, super-structure can be as real in terms of having a concrete impact on people’s lives as material and structural variables. However, it must be also recognized that what makes ideology concrete is its articulation with social structure. Continuing with the example of Afghan women, enforcing ideological conformance depends on a social structure that will in fact facilitate punishment for non-conformance.

Thus, in making assumptions about causation, understanding how an aid intervention might be successfully introduced, and approaching the decision-making process regarding appropriate aid-interventions, priority is given first to the constraints and opportunities made available by the unique environment where a culture is operant. This includes demographics, availability of raw materials, and productive technologies. Priority is given next to social structural constraints and opportunities found in existing institutions. And ultimately, consideration is given to ideological and religious constraints and opportunities.

Again, none of this is to say that ideas and states of mind are not of importance. The point is simply that in understanding what interventions will ultimately be most practical, aid practitioners must understand what already exists first in terms of environmental constraints, second in terms of social-structural constraints, and only then in terms of ideational constraints.

The figure below is an organization template that illustrates the hierarchical categorization of variables in the Infrastructure, Structure and Superstructure in the context of studying a value-chain map. The technique is something that I have called elsewhere a MEVMS map. Note that when defining the infrastructural, structural and superstructural opportunities and constraints in which the map must be understood, we do not list every single aspect of the Infrastructure, Structure and Superstructure. Rather we list those categories that are relevant because they exist and are either auspicious or a critical limitation to aid interventions.