To understand food security and resiliency of rural Haitian households it helps to understand the crops, fruit and nut trees that are available in the country and the strategies rural Haitians use to manage them. Here I offer a brief summary of the crops and trees, the adaptability of the food production system they are a part of, and the logic underlying their cultivation, consumption and sale. Most of the data presented is from a random 405-household survey conducted in the southern Haiti Department of the Grand Anse in 2018 and a 1,586 household random survey conducted in North West Haiti commune of Jean Rabel in 1997, however, the findings are consistent with dozens of other surveys and investigations we’ve conducted on crop and tree cultivation in Haiti over the past 30 years.

Haiti Anthropology Brief: Cropping Strategies in Haiti

The crops

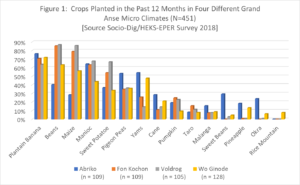

What we find in Haiti–a country characterized by a high geographic frequency of micro climates caused by altitude variation and rain shadows–is that there is a significant difference in the importance of one crop vs. another in the different micro-climates, but the major crops are the same for each zone, regardless of the differences in altitude or rainfall. For example, the 10 major crops planted in four different zones of the Grand Anse are the same crops, but planted with different intensity.

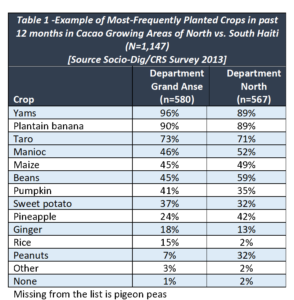

Table 1, below, underscores the fact that the same crops are planted with similar intensity even in region as geographically distant from one another as the Department of the North and the Grand Anse in the extreme South.

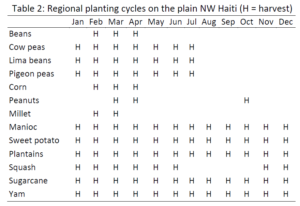

The crops seen above include seasonal cash crops harvested all at once, such as black beans and corn, but most can be thought of as survival crops, meaning hardy, usually drought resistant, some of which can be stored in the garden, on the vine or root, such as yams, sweet potatoes, malanga, taro root, and manioc. Others may not store on the vine, but they yield consistently throughout the year, such as pigeon peas, plantains, and bananas. Indeed, the most important and consistent feature of these crops is that most do not require simultaneous harvesting but rather are crops that yield slowly over a period of several months or year-round, making several staples available in the garden in every month of the year (see Table 2).

Below is a brief review of the characteristics of some of the most important of crops planted in rural Haiti, a review that strongly suggests the underlying logic behind cropping strategies in rural Haiti and the resiliency of the strategy.

Sweet potato, arguably the most commonly planted crop throughout Haiti go into a state of dormancy during drought and then come back vigorously at first rain and may yield as much as twelve metric tons per acre on as little as four inches of rainfall. The more it rains, the more the vine produces (see Bouwkamp 1985; Onwueme 1978).

Manioc is one of the most productive tropical food plants on earth in terms of calories produced per square meter, surpassed only by sugar cane and sugar beets. It needs more rain than sweet potatoes to grow, but it is more tolerant of drought, easily surviving dry periods longer than six months and it grows in marginal soils. Unlike sweet potatoes, manioc has the unique ability to be stored in the ground and is hurricane proof because it can lose all its leaves and its branches may break but the root, which is the only part of the plant Haitians eat (the leaves are edible too but not eaten in Haiti), will not die. After drought or hurricanes the plant draws on carbohydrate reserves in the roots to rejuvenate itself (see Toro and Atlee 1980; Cock 1985).

Pigeon peas are a bush-like plant with roots reaching six to seven feet beneath the surface, deeper than cassava, making the plant highly drought resistant. When drought does strike, pigeon peas shed all their leaves and go into a state of dormancy just like manioc, coming back to life when the rains return (see Nene et al. 1990). Moreover, its stalks provide an excellent fodder for livestock.

Millet is another wonder crop that yields with minimum rainfall. The roots reach more than eight feet beneath the surface, enabling the plant to withstand over two months of drought. When the crop is entirely lost to drought or has been harvested, the stalks can be cut back and with the first rains the plant will begin growing again; it can potentially yield 10,000 seeds for every seed planted, it grows on land otherwise lost to salinization, and it’s hard kernels store as well or better than wheat (see Nzeza 1988).

Peanuts although not very tolerant of saline soils, are even more drought resistant than millet and can be planted in sandy soil and in the chaparral where only cacti and xerophytic plants are found. Once it rains, the peanuts grow fast and will yield with only a couple rain falls. It is also the premier high yield cash crop in the mountains, taking over the role that corn and beans fill on the plains (see Nzeza 1988).

Corn (Zea mays) and Cowpeas (Phaseolus vulgaris)[i] are not highly drought resistant although there are short season varieties like those originally planted by the Taino Indians. Beans and corn are among the few concuco plants harvested all at once and are one of the most significant sources of income available for conuco farmers. Corn is the most productive domesticated non-tropical plant species on earth in terms of calories per square meter (Newsom 1993; Prophete 2000).

Plantains and Bananas (Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana) are planted where there is moist, irrigated soil. They are propagated from suckers (shoots). They take 9 to 10 months to begin yielding fruit, but in the meantime, the garden can be intercropped with fast yielding plants such as beans, corn, millet, and melon. By the time these other crops are harvested bananas are reaching a height where they begin shade out other vegetation, something that eventually eliminates the need for weeding. Like so many other crops preferred in Haiti, bananas yield fruit all year round, giving a steady supply of food for consumption or sale in the market. But if necessary, they can be cooked and eaten at any stage of growth. Indeed, neither plantain nor bananas are ever harvested ripe. Once they are harvested, they will keep for two to three weeks. Their thick skin (peel), helps protect them from bruising during transport and keeps them from becoming contaminated. Back in the garden the plantain or banana plant can be allowed to continue producing bunches at its own rate, or it can be cut back to the level of the soil, allowing for another cycle of intercropping while the plant rejuvenates itself. A single plant can continue producing fruit for 50 years.[ii]

The other lesser but still important crops all fit into an agricultural strategy that is clearly selected more for eking out a living in the face of an unpredictable market and natural environment than for participating in the world economy: Lima beans, which are inter-cropped with corn, are nitrogen fixing and begin to yield two to three months after harvest and continue to yield for as long as there is sufficient rainfall. Black-eye peas are a nitrogen-fixing, extremely drought and disease resistant vine that will grow fence posts or side of house; it provides a continual production of beans. Pumpkins and squash also yield continually as long as there is rain. The most popular yams (yam reyal) can be planted during dry spells and will begin to grow with the first rains. Like manioc, yams it can be stored in the ground indefinitely, serving as an important food during droughts and other crises. Sugarcane endures for years, propagates itself without human intervention, can be harvested at any time after it is mature, and will grow back after being cut. Perhaps most importantly with regard to sugarcane, the hard-fibrous exterior locks in water while the roots extend some eighteen feet underground, making it a completely drought-resistant source of water and high-energy food for both people and animals.

The Underlying Logic

It’s clear from the characteristics of the crops the rural Haitian cultivator prefers that there is an emphasis on survival and the provision of food. Drought, flood and wind resistance are combined with high yields and long periods of production (versus a single harvest). Other factors evident in the crops descriptions and that seem to determine what crops are planted is that the crops can be managed with minimal effort in a wide range of soil pH conditions.

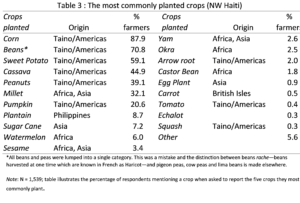

The primacy of survival vs. maximizing production and yield, is underscored by the fact that the five principal crops planted in contemporary Haiti–corn, beans, sweet potatoes, cassava, and peanuts—were five the very same crops Taino Indians who inhabited the island during pre-Columbian times (Newsom 1993; Rouse 1992). To this basket of Taino domesticates early colonists and slaves added three of the most drought resistant crops on the planet: sorghum, millet, and pigeon peas, crops that continue to be of great importance to rural Haitian today, and the lima bean, a quick growing, high yielding legume (Moreau 1797). A summary of the major crops planted in rural Haiti and their origins is presented in Table 3, below.

The Strategy is Also Low-risk and Low-Cost

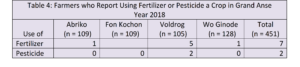

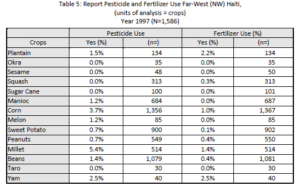

Similar, to the emphasis on survival crops, cultivation in rural Haiti is a low-risk and low-input activity. In surveys we’ve conducted throughout the country over the past 30 years we consistently found that only 2 percent or less of farmers in any given area use chemical pesticides, and less than 1 percent use chemical fertilizers. The use of these inputs is almost always in association with exclusively cash crops, such as vegetables, tobacco and to a lesser extent beans. Even practicing of compost is rare to non-existent. Farmers will turn livestock loose in their gardens after harvests, but the explanation is always to feed the animals, seldom do cultivators mention the value of animal dung as enriching the soil. In some areas of Haiti people will specialize in plowing with oxen and sell their services to other cultivators (specifically on the Plateau Central and Les Cayes area), but for the overwhelming majority of cultivators in Haiti, even those in areas where oxen are used to plow, human labor, hoes and machetes are the rule. Tractors and pumps are used by less than 1 percent of cultivators in the country. Below are a couple examples from surveys, one a 2018 Grand Anse survey and the other a 1997 GTZ survey in NW Haiti.

Storage in the Form of Cash

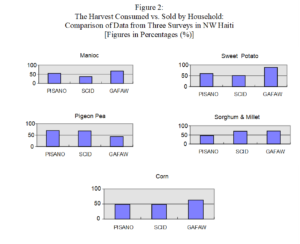

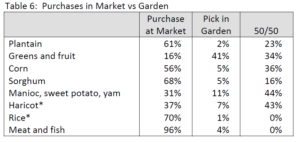

Despite the emphasis on survival and resistance to drought, flood and high winds, it should also be understood that most Haitians are not producing exclusively for consumption. In the figures below, a comparison of three different surveys conducted in remote areas of NW Haiti, it can be seen that even with ‘survival’ crops such as pigeon peas and manioc, cultivators report selling as much of their harvests as they consume.

In the below chart we turned the issue around and asked where people get what they eat. The importance of the market is again evident (Figure 3).

The data illustrates the extent to which Haitian producers are largely market oriented. Micro-climates that have complementary seasons (mountain vs. plain), mean that rather than risk storing crops or going through the chore of processing them, farmers can sell their crops in one of the weekly regional markets (read about the Haitian Internal Rotating Market System), and store surplus in the form of cash. This is the prevailing pattern throughout Haiti. The practice hurts cultivators to a certain degree in that there is a significant drop in market prices at harvest time as other cultivators also dump produce on the market and scramble to store their surplus in cash. But at the same time it gives them a safe medium to store produce–a near impossible task in humid sub-tropical environments–and has given impetus to the vigorous intra-national rotating market system, something dominated almost exclusively by women. Rapid sales of the household’s harvest of cash crops allows women to extend the money from harvests by rolling it over in marketing activities, using the proceeds to meet household needs (see Defining the Madam Sara and Madam Sara vs. Komèsan).

Fruit and Nut Trees

While I do not here elaborate extensively on fruits and nuts, it is useful to make mention of them because they so neatly complement the cropping strategy described above. It should be emphasized first, however, that trees in rural Haiti are not cultivated with the same underlying logic as crops. Trees are arguably not precisely domesticates as they typically are not deliberately planted but rather selectively permitted to grow. The seeds propagate easily near households because it is there that people most often discard seeds. If one of the seeds sprouts and the people in the household like the tree where it is, they do not pull it up. They may even put a makeshift fence around it to guard it from goats. They may even dig the sapling up and move it to a more auspicious location. But seldom do rural Haitians deliberately germinate and plant a tree, or even purchase a sapling to be planted.

All rural Haitians have access to fruit and nut trees and most households own them. For example, Figure 3 below summarizes the trees owned in the year 2018, 405-respondent random household survey in the Grand Anse mentioned earlier on.

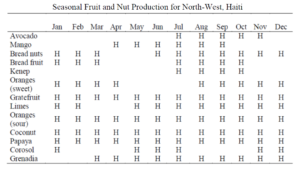

Similar to the crops seen earlier, trees provide a nearly year round supply of food. While we provide no data here, we know anecdotally and from focus groups that more fruit and nuts from trees is consumed locally–for free–than sold in the market. We also know in the face of food scarcity, rural Haitians cook and eat unripened corosol, green mangos (as well as guayav chou palmis, zamond, kenep, papay, korosol zombi, kachima, kayimit (2) pye bwa, manje fri seriz/cherries, siwal).

Wild Plants

A final mention is made here regarding consumption of wild plants, meaning plants in which Haitians take no role in planting, nurturing, or protecting. The significance of wild plants in rural Haiti was partially captured by CARE’s 1994 baseline study in which 58% of households in CARE’s 1,400 household Northwest sample reported eating them. The types of edible wild plants together with some that are more often thought of as domestic are listed below, some are given in Kreyol only:

- Wild yams: Dala (manje siklon, grate li kom manioc ame ), chat, galata

- Wild beans, greens and stalks: piyant (used as a kind of coffee), karaibe, doliv, laman, epina wouj , lyann panye, kou pye, lalo, chou mantad, chou kore, kresan, konkonm, zeb egwi, bondye bay

- Wild cabbage

- Fruits that grow on vines: Militon, Grenadia

- Tree seed pods that are eaten from trees during crisis: bwa fè (grenn), bwa dom (grenn nan kos), bwa blan (grenn nan kos—tankou pistach), tamarin (kouvre grenn nan kos), and brizie (grenn)

WORKS CITED

Bouwkamp, John C. 1985. Sweet potato products: A natural resource for the tropics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

Cock, James H. 1985. Cassava: New potential for a neglected crop. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Nene, Y.L., Susan D. Hall, and V.K. Sheila, eds. 1990. The pigeonpea. Andhra Pradesh, India: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics.

Newsom, Lee Ann. 1993. Native West Indian plant use. PhD diss., University of Florida, Gainesville.

Nzeza, Koko. 1988. Differential responses of maize, peanut, and sorghum to water stress. Master’s thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Onwueme, I.C. 1978. Tropical tuber crops. New York: John Wiley.

Prophete, Emmanuel. 2000. personal communication, Vegetal Production Specialist MARNDR.

Rouse, Irving. 1992. The Tainos: Rise and decline of the people who greeted Columbus. New Haven: Yale University Press.

St Mery, Moreau. 1797. Description de la Partie Francaise de Saint-Domingue. Paris: Societe de l’Histoire de Colonies Francaises, 1958 v. 2.

Toro, Julio Cesar and Charles B. Atlee. 1980. Agronomic practices for cassava production: A literature review. In Cassava cultural practices: Proceedings of a workshop held in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, 18-21 March 1980. Ottawa, Canada: International Research Development Research Centre.

NOTES

[i] The relative importance of black, white, and red beans—commonly called cowpeas– is obscured by having been lumped together with the ubiquitous pigeonpeas (locally called pwa kongo).

[ii] A giant herb, not a tree, banana and plantains are the largest plant without a woody trunk or stem. The part that resembles a trunk is actually leaves that grow straight up from an underground stem. The leave grow tightly together to form a tight sheath, the trunk, eventually branching out. The fruit is actually a giant berry.