Originally published in January 2012 on Open Salon

Madan Sara

The madam sara (or phonetically madan sara) is the itinerant female Haitian market woman. She is the principal accumulator, mover, and distributor of domestic produce in Haiti and as such represents the most critical component in what anthropologists have long called the internal Haitian marketing system, the one upon which the redistribution of produce from Haiti’ some 700,000 small farms depends.

Komèsan

Her opposite, and what can be conceptualized as her figurative nemesis, is the komèsan (distributor), the handler of durable staples imported from lòt bo dlo, overseas.

Economic Sabotage

The komèsan in provincial towns employs a devious, if unplanned, tactic, one that undermines her madam sara rival and the internal marketing system in which she operates: she gives her credit. But not any credit. She offers her madam sara rival sacks of imported flour, rice, corn, and sugar at no interest.

The sara in need of cash often takes the bait and is thereby drawn into an insidious web. The sara exploits the credit as a loan. She accepts the contract but then turns around and sells the sacks of food for less than cost, for she knows that even if she takes the loss, she can use the money to make far more profit in the internal marketing system: by a factor, adjusting for time, of about 25 to 1).

But what seems like a good deal has a hidden, long term cost. The effect is an artificial price reduction for imported goods because the purchaser can now resell the imported food at a price below the real cost. By doing this, by selling the imported foods at less than cost, the madan sara has de facto used profits from the Haitian internal market system to subsidize imported US and EU grains–crops that have already been heavily subsidized by their respective overseas government, not least of all the United States, France, and Canada.

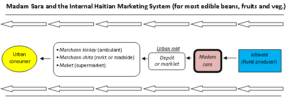

Below is a full diagram of the urban market flow for Haitian sector of the Global Marketing System. Note that the machan kay (women who sell a particular good out of their home) who deals in imported staples does not exist in the urban areas (however, there are marchann kay in both rural and urban areas who specialize is items such as leaf tobacco and other non-staple items).

More on the Madam Sara

The term madan sara (pronounced ma-dan sé-ra according to anthropologist Gerald Murray) derives from a highly gregarious, little yellow and black bird introduced to Haiti from Sub-Saharan Africa. Known in English as a Village Weaver (Ploceus cucullatus), the female seems to be constantly collecting food and twigs and carrying them back to her nest, usually in a tree full of hundreds of other nesting madan sara. Similar to the buzz of voices heard from Haiti’s rural markets, the traveler knows when approaching a colony of madan sara because of the noisy din of chatter from hundreds of busy birds. Madan sara acts as the critical market link between rural producers and the urban consumer, most importantly the 30% of the national population who live in Port-au-Prince, many of whom work for wages and receive remittances from overseas migrants. Madan sara are predominantly rural woman who purchase produce in rural areas; then transport the goods directly to larger markets or Port-au-Prince; seldom venture into unfamiliar territory, but rather operate either in their native rural area or an area with which they are familiar and have kinship relations. Some are heavily capitalized and highly visible merchants who use others to aggrandize produce and use public truck transportation; but most are independent, individual entrepreneurs, who travel alone or in small groups, move their cargo on foot, donkey or mule.[i] When they get to the city madan sara either sell their merchandise immediately and return home without sleeping (to sleep with friends or family means they will have to shed some profits, however small); or they sleep in depòt (storage facilities) with their merchandise–which they are loath to leave unguarded–and they stay there until they have sold their goods or until their fixed and trusted kliyan (clients) with whom they have a long-term trade relationship and most of whom fall into the category of marchann chita,–sitting merchants–or machann kinkay— literally “merchants of lots of things”–women who typically have little capital or operate on credit from the madan sara, (typically 2 to 3 days).

The key to understanding the behavior of the madan sara is understanding that she focuses on rural produce, specializes in whatever commodities are seasonally available in her activity zone, and almost as a rule return to the rural areas with no merchandise and the reason is because the most lucrative market for the madam sara is not the cash scarce rural areas where they would have to wait a long time to recuperate their investment, but the cash flush urban market where they can roll their capital over rapidly and return to the rural areas to repeat the cycle (the profits for a madan sara going from Segen–above Jacmel– to Port-au-Prince, for example, is 100% for a one day walk and one to two days of selling; if she goes to Kay Jacmel it is 50% with same day sales; if, on the other hand, she buys a sack of rice, her profit is 20%–one fifth that of the madan sara destined for Port-au-Prince– and her average turnover rate is 15 days—five to seven times as long as the madam sara destined for Port-au-Prince). Madan sara seldom take standard loans (because it cuts too heavily into their own earnings).

More on the Komesan

The komèsan is the key figure representing the incursion of the global market economy and foreign produce into Haiti, a link in what can be analytically categorized as a market chain separate from the sara and the internal system, one that moves in the opposite direction, both literally, in terms of the primary flow being urban to rural (in contrast to rural to urban), and figuratively, in terms of its opposition and undermining of domestic production.[i]ii] The chain begins with the importer, then moves to the various levels of distributor (komèsan) and warehouse owners (met depòt). At that point the chain either moves directly to consumer, as in the case of hardware and mechanized goods or, in the case of food staples, moves to marchann chita who sit in the market or by the roadside, the jambe chen (little street restaurants found throughout markets, bus stations, and neighborhoods), the boutik (small stores also found throughout urban area, provincial towns, and rural hamlets) or the boulanjeri( bakery) that are found not only at the higher echelons of society but in the simpler form of stone-hearth ovens located throughout neighborhoods,bidonville (slums), provincial towns and even in the most rural hamlets.

Notes

[i] Madam sara in the Southeast activity zone can be classified into two categories: the ti madm sara (the little madam sara) and the gwo madam sara(the big madam sara).

The ti madam sara purchase produce in the interior, either in the garden of the producer or in the rural market place. She then either, 1) hauls the merchandise to Jacmel or another of the principal coastal market centers where she earns an approximately 50% market up selling to other better capitalized madam sara, or 2) she takes the goods herself to Port-au-Prince where she earns approximately 100% on her investment.

Although many women make the trip to Port-au-Prince on foot, a principal factor that determines her choice of destinations is the availability of animal transport (the lower capitalized ti madam sara avoids the cost of using paid transportation, keeping this revenue for herself). If she does not own an animal she may be more inclined to carry the goods on her head to the coastal markets with the expectation that she will earn about 125 goud for her effort. Stronger women can who can carry two loads (chay) can double that sum .

Thus, those how own a donkey or mule are more likely to chose Port-au-Prince as her destination. The animal allows her to haul three to five times the quantity that she herself could carry. But she also incurs more expenses than her ambulant counterpart; she leaves her animal in the Kenscoff area; she then pays a taxi-truck to transport the goods down the mountain to the Petion Ville. As mentioned in the main text, she will purchase nothing for the return trip home and the reason is that it is more profitable for her to return home and use her precious capital to make another purchase and a yet another trip to the vibrant urban market. Madam sara who live in highland Jacmel typically make the trip to Port-au-Prince twice per week. Those that go to the coastal markets can make the trip daily.

The gran madam sara has significantly more capital at her disposal than the ti madam sara. She either accumulates stock in the highland market centers or she purchases stock in the more accessible coastal markets. She then pays truck transport to take her goods to Port-au-Prince where she checks into the depots as described in the main text. She gives credit to.kliyan as discussed The largest of these women use assistants, often men, who are variously known for their different tasks as by the terms maladieu, koutiere, and gestioné. But the overwhelming majority of sara purchase their own goods.

[ii] An heuristic comparison can be made with the market system in the neighboring Dominican Republic (DR) where neither the madam sara nor the rotating market system exist (except in the border areas where one does find rotating markets and, regarding the madam sara , historio-ethnograhically in the rural areas surrounding the central city of Santiago where until recently operated a famed type of madam sara on her donkey; the Dominicans have even built a statue to commemorate her). In the DR it is male truck owners/drivers who fulfill the redistribution function analogous to the Haitian sara , purchasing domestic produce from farmers and then redistributing them through male dominated market system. The buyers in the Dominican open markets own stores (colamados) or they are other truck-owner-driver intermediaries who sell out of their vehicle, riding through neighborhoods announcing over a loud speaker their produce, or who distribute directly to colmados found throughout both rural hinterlands and urban barrios. The colmado also warrants a special clarifying note because they play a central re-distributive role on par with the Haitian rotating markets. Interesting in this respect, provision of credit is a fulcrum point of the colmado system while Haitian boutik generally does not provide credit to customers. Indeed, the colmado is often the point of most intense social activity in barrios and pueblos throughout the country.