Rural Haitian women assiduously negotiate sexual acquiescence to men and they do so with the goal of material gain. Ira Lowenthal (1984: 22) first described this behavior in detail when he reported that women in his research community referred to their genitals as intere-m (my assets), lajan-m (my money), or manmanlajan-m (my capital), in addition to tè-m (my land); a common proverb was, chak famn fet ak yon kawo te—nan mitan janm ni (every women is born with a parcel of land—between her legs). Lowenthal (1984) described this type of female commoditization of sexuality as a “field of competition” wherein women are at a socially constructed advantage: men are conceived of and taught to think they need sexual interaction with women, while women portray themselves and are taught to think of themselves as able to get along without sex and thus are able to exact material rewards for sexual contact with men. Called “gendered capital” by Richman (2003: 123), these sexual-material values are universal in rural Haiti and apply whether the woman in question is dealing with a husband, lover, or more casual relationship.

Jean Rabel, where I did my doctoral research in the years 1990 to 2000, is no different. As I have shown elsewhere, the commoditization of womanhood described above is linked to a sexual division of labor and rights and duties associated with control of the household, children, extra-household income, and female marketing activities (see Sex, Family and Fertility in Haiti); but here I simply want to describe “gendered capital,” or what may alternatively be described as rural Haiti’s sexual-moral economy, and show how it combines with the pronatal sociocultural fertility complex to make extremely high fertility possible despite conditions aversive to conception. In accomplishing this I will illustrate my points with songs that rural adolescent girls in Jean Rabel compose, sing, and act out in theatrical performances called téat. Reminiscent of Jorge Duany (1984: 186), who stated that the traditional song “cannot fail to create and recreate the most important social values of the group that produced it,” and John Szwed (1970: 220), who wrote that “song forms and performances are themselves models of social behavior that reflect strategies of adaptation to human and natural environments,” the songs I present below highlight the uniform sexual-material-domestic value system found throughout rural Haiti.

Girls’ Téat Songs

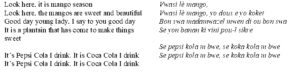

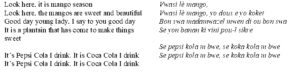

When school is out for the summer, girls in rural Jean Rabel neighborhoods form dance troupes called téat (theater). The troupes are formed by the girls themselves. There is no adult sponsorship or leadership. The girls are all prenuptial, have not yet borne children, and are generally aged ten to twenty years. Older girls appoint themselves troupe directors and instruct the younger girls in daily practices. The girls dress in short skirts and sing while performing the latest erotic dances such as the buterfli (butterfly), a dance in which the girls gyrate, opening their legs wide and rocking their abdomens out toward the impromptu audience as they descend lower and lower toward the ground. The songs are improvised from bits of other songs and spiced with the girls’ own creative additions. The most popular songs are imbued with sexual connotations, such as the following, in which the girls celebrate their own budding sexuality with respect to the sexual bravado of men:

As can be seen, the song relies heavily on metaphors. In this particular song, informants explained that mangos, ubiquitous in Haiti and the all-time favorite fruit, symbolize the girls’ budding young breasts. The eroticism of fruit and particularly a mango with its soft juicy flesh is clear to native speakers, the declaration that “it is mango season,” means that it is time to eat mangos, the fruit is ripe, or rather, the girl has come of age and she is ready to engage in sexual relations. The “good day young lady” is an introduction to the young woman. The next line reveals the speaker, a man, represented as another fruit, a plantain, which has come to add sugar (sikre). The plantain also happens to be the most phallic shaped fruit in Haiti leaving little doubt for analysis (any remaining doubts are erased by snickering Haitian informants). The references to Pepsi and Coca Cola are metaphors for prestige. In Jean Rabel these are, aside from beer, the most expensive locally available beverages and they have correspondingly high prestige value, representing the speaker as a high roller.

Thus, the songs I use below to illustrate the sexual moral economy all touch on the theme of sex. The songs also, as will be seen, highlight female ideals and aspirations, gender relations, control over resources, parent-daughter relationships, and most importantly of all, the rules, expectations, and norms associated with male-female sexual interaction, all of which, I argue, are interrelated in what might be called a type of sexual-moral economy. The analysis, conducted with the assistance of local informants who helped explain the double and sometimes triple meaning of the words to the songs, begins with a look at a socially constructed problem that Jean Rabel women have and the representation of that problem in téat songs.

Male Sexual Aggressiveness

A common expression used by women in Jean Rabel is “men are dogs” (gason se chyen); “men cannot get by without having sex” (gason pa ka rete san fi). No strong prohibitions exist in Jean Rabel against men seducing young women, and Haitian laws that prohibit sex with girls under fifteen are not enforced. Men in their fifties, sixties, and even men in their seventies are referred to with regard to their sexuality as jenn gason (young men), and powerful men may have four or five and even six common-law wives, a source of pride and esteem. Thus, young women are badgered and cajoled by a relatively large pool of socially eligible, sexually active, and highly aggressive men. The most common seduction tactic is for a man to catch a woman on a footpath or while she is alone in the kitchen. He will seize her arm so she cannot get away, playfully trying to pull her near, proclaiming his desire for her and pleading for her sexual affection while whispering promises of money and gifts.

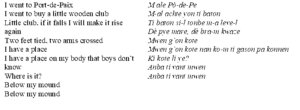

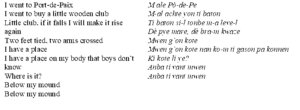

As counter-intuitive as it might first seem, females arguably play an influential role in encouraging aggressive male sexual conduct. They take part in propagating the myth that a celibate man can go insane, become ill, and may die. They tease timid boys and ridicule celibate men, taunting them with names like jay-jay (retarded) and masisi (homosexual); and they goad younger brothers and even sons into pursuing nubile young women with comments that sound to the Westerner like admonitions to rape: “you must bother them, don’t let them get away, grab them” (fo ou jennen yo, pa kite yo ale, fo ou kenbe yo). The influence of women in conditioning male attitudes begins at an early age, as exemplified by the fondling of the genitals of male infants, toddlers, and boys up to the ages of nine and ten years, something so thoroughly engrained and accepted as to appear to the foreigner to be below the level of awareness. The fondling is made easy by the custom of making prepubescent boys go without pants. Examples of the context in which it occurs include the following: a rural woman nervous about being interviewed distracts herself by fondling a four-year-old’s penis all the while she is answering my questions; a nineteen-year-old woman sitting on a bed in a dimly lit hut talking to me reaches beside her and, without ever looking at what she is doing, begins fondling the penis of a naked eight-year-old boy, doing this as nonchalantly as if she had just picked up a pen or any other stray object off the table; a twenty-two-year-old woman excited to see her two-year-old nephew tickles his penis, lifts the boy, swings his body up to her face, and pops his penis playfully into her mouth. The toddlers and young boys are not indifferent to the treatment and react with enthusiasm, smile, and laugh when given the attention and often follow their significant female others around. The song below playfully alludes to, or is at least suggestive of, the active role that Jean Rabel females play in determining male sexual identity and the coy preservation, or at least guarded access, to their own sexuality,

The reference to “a little wooden club” is an obvious phallic symbol (clubs are not something that everyone in Jean Rabel is walking around with and while old infirm people might use a cane, purchasing one is nonsensical). The line “if the club falls” signifies the loss of an erection and this image is reinforced by the next line, which in Kreyol uses the verb leve (rise) and anko (again)—“I will make it rise again”—rather than ranmase, the Kreyol word for “pick up”—“I will pick up the club.” The next line, “Two feet tied, two arms crossed,” suggests restraint or prohibited access to the woman’s sexuality. The remaining lines, “I have a place boys don’t know . . . below my mound” are a proclamation of virginity and chastity: “below my mound” is translated from “anba ti vant mwen,” it literally means “below my little stomach.” In effect, the girl may choose, “buy,” a penis to fondle, making it rise again and again, but her own genitals have never been “known” by boys.

Chastity and the Commercialization of Female Sexuality

Although women encourage men to be sexually aggressive and inculcate boys in the association between females and sexual stimulation, they do not present themselves as so willing to comply with the amorous wishes of men. The socially constructed attitudes of Jean Rabel women are contrary to that of men. While admitting that they desire sex, women define themselves as not needing it. Despite the “hot” tone of the songs, they always include restraint, as in the previous song, “two feet tied, two arms crossed . . . I have a place that boys don’t know.” All Jean Rabeliens know and commonly say “girls do not flirt with boys” (fi pa konn koze a gason), it is the boy’s job to flirt. A sexually aggressive woman or one who engages in sex for pleasure is criticized, as in “she is such slut” (tann li bouzen), or insultingly called “nymphomaniac” (piten). A young woman who has not had children and is not in union will always insist she is a virgin, no matter what her personal sexual history might be; and as a matter of identity and pride most Jean Rabel women insist, often and quite publicly when the subject arises, that they can live without sex. They describe themselves as sipòtan (able to tolerate abstinence). They maintain an attitude of sexual indifference, describing excessive sexual intercourse as painful, a burdensome service they provide to men, and while admitting that sex can be fun, and even exalt its pleasures, they consider over-manifestations of their own biological interest in sex to be a fault, something evident in attitudes toward vaginal secretions during sex. Commonly thought in Western society as a biological sign of sexual arousal, Jean Rabel women who become more than slightly wet are called bonbon dlo (watery vagina), considered disgusting; and women make efforts to dry themselves if the condition manifests itself during sex, even if the sex is with their husbands.

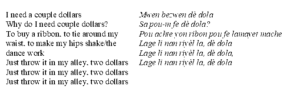

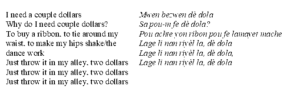

As seen with the studies mentioned from elsewhere in rural Haiti (Lowenthal 1987; Richman 2003), the defining feature of female attitudes toward sexual relations in Jean Rabel is that they view their sexuality as an economic asset. They say that they are born with a kawo of irrigated land between their legs (the most valuable asset in rural Haiti) and they refer to their genitalia in exchange terms, byen-pa-m (assets/goods), excusing each other for engaging in an affair outside of conjugal union so long as the man reciprocates with material rewards: “She is a woman isn’t she? It’s her right”; “Getting by is not a sin” (degaje se pa pech). Men are acutely aware of the rules, and they commonly say “in order to have a woman you must have money” (pou gen fi, fo gen lajan) and “women eat/devour men,” meaning they take all a man’s wealth (fi konn manje gason). A woman’s right to exchange sex for financial reward is exalted in the following song, which according to informants is actually a metaphor for sex and a demand for payment.

This song humorously summarizes the attitudes with which Jean Rabel women imbue their sexuality. As with the other songs, it is a play on words, but words already very sexual. The Kreyol term lamayet designates a sexy dance movement, and informants explained that it is combined with the word mache (to function, operate, work) to form the implied verb “to hump”—make the dance (lamayet) function, or less suggestively, to enable the girl to better shake her hips. Lage literally means “to let go” and a Haitian male “come on” is lage-m nan reyal la, which means “let me loose in your alley.” But in terms of money, a very common colloquialism is lage sink goud nan min mwen (let a dollar go in my hand). Thus, lage li nan riyèl la is a play on these two expressions and to state it literally it means “just throw the money in my vaginal canal.” So the song is a rather ingenious circular play on words that reduced means “I need two dollars. Why? Because if you want me to perform sex that is what it costs to get my hips going. So just throw the two dollars right in my vagina.” The Jean Rabeliens who reviewed these songs with me could hear this particular song several times in succession and would laugh hysterically every time.

Conjugal Union and Sex and Infidelity

With the guarded notion that sex begets children, it is considered to be a Jean Rabel woman’s God-given right to use her sexuality to acquire material support. If a man wants to claim exclusive sexual access to a woman, he must purchase that right with gifts and promises (or lies). In the event it is a young woman still living in her parents’ home, the man must first fianse the girl (become engaged), which requires giving a gold chain and gold earrings to the girl. And, as discussed in a later chapter, if the man wants to maintain his right to his wife’s sexual fidelity, he must build her a house, plant gardens, and tend livestock for her.

A man who fails to provide continued assistance to his partner can be legitimately cuckolded. However, not unlike the Hutterites, a woman who is in a union with a man who steadfastly plants gardens and tends livestock to support the household must be unfalteringly faithful, even if her partner or husband decides to enter into union with one or a series of other women.

Any sign of a woman’s infidelity sets neighbors, family, and friends buzzing with gossip and can damage her reputation in the community for life. With an act of infidelity a woman risks destroying her existing union and diminishes the probability of entrance into a subsequent union with a respectable, or at least a financially able, man.

That is the ideal pattern of behavior. In light of the geographical mobility of many husbands and the scarcity of income, it is often not possible to maintain these standards. The sexual mores seen above and desire for children set up a grey area where women are often not able to conform. As will be seen below, fortunately, or perhaps as a consequence, women and their families are able to appeal to myths, fictive illnesses such as arrested pregnancy syndrome, and superstitious rationales that convince men to accept paternity for children that are not biologically their own. Appealing to the same fictions, men readily accept.[i]

Pregnancy, Paternity, Sex, and Sorcery

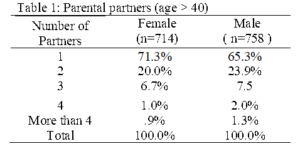

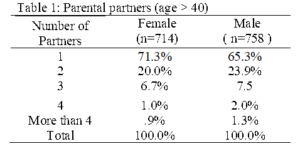

In Jean Rabel, 29 percent of women and 35 percent of men over forty years of age report having borne children with more than one partner, a suspiciously imbalanced proportion (table 1). Moreover, there is the demographic oddity of men reporting an average of more living offspring than that reported by women: 6.3 versus 5.2.[ii] The explanation for why the average number of children born to men is greater than the number born to women is that women often assign paternity to more than one man; 13 percent of men in one of the research communities were reported—by friends, family and neighbors—as having been “clobbered-with-a-baby” (kout pitit), an expression meaning that they had at least one child who friends and neighbors reported was actually the child of another man. In a later chapter it will be seen that men have a definitive economic interest in claiming paternity for children that are not their own. This interest is manifest in attempts to identify with and appease women. Some men make displays of sympathetic labor and illness when their wife is giving birth; and the most common paternity suits are not women suing for child support but men suing for exclusive paternity.

To clarify or explain doubted paternity or controversial sexual encounters, a variety of universally accepted beliefs can be invoked. Women and men explain away sexual infidelity as having succumbed to magic spells purchased from bokor (witch doctors), spells that make people fall in love, that stupefy women, that give men the power to take an unwilling girl’s breath away so she can not scream, and that make a married man irresistibly attracted to another woman (kout maji). A man uncertain that he is the father of an infant has recourse to a blood test; he pricks his own finger and puts a drop of blood on the newborn’s tongue. As everyone in Jean Rabel knows, if the man is not the biological father the baby will die instantly.

A belief that deserves special attention is the fictive illness known as perdisyon, mentioned above. Perdisyon is diagnosed when a sexually active woman who would otherwise expect herself to be pregnant begins to menstruate again (due either to an actual pregnancy ending in spontaneous abortion or some other amenorrheic condition). In search of an explanation, she visits leaf doctors and other specialists, who are quick to tell her what she wants to hear, she has a baby inside. The explanation provided for the failure of gestation to proceed is invariably that a rival or a jealous lover of her spouse—or boyfriend—is using sorcery to prevent the fetus from growing. The phrase mare nan vant is used to describe the condition and it literally means “tied up in the stomach.”

Perdisyon provides a convenient rationale for the swelling stomach of a woman who has not seen her emigrant husband for more than the preceding nine months. It also provides the woman and her parents grounds to pressure a man into beginning to swenyen (care for) her and the imaginary fetus. That the illness is widespread and accepted by both women and men is evident. Only two of twenty-six women interviewed in Makab had any doubt regarding the veracity of perdisyon and even men typically responded to the question: “has your wife ever carried a fetus longer than nine months?” with replies such as “Thank God no, we haven’t had that problem yet.”[iii]

Elsewhere in Haiti, researchers have found similar trends. Murray (1976) found that one-third of the women in his research village had experienced at least one bout of perdisyon, and in a large country sample of deceased women Coreil et al. (1996) found that 6 percent of a sample of 1,287 rural and urban women were in a state of perdisyon at the time of death—something they explained had nothing to with death but was a reflection of the widespread belief in the fictive illness.

Whether magic charms, spells, “blood tests,” and arrested pregnancy syndrome really exist is unimportant. What is important is that accusations of sorcery and magic provide convenient excuses for lustful or financially inspired sexual escapades or infidelity that result in childbirths and hence cannot be hidden away or dismissed—as often is the case in the Western version of the extramarital affair. Belief among the population in the supernatural phenomenon described above is unanimous. As a French doctor who lived in Jean Rabel for three years remarked, “these are not things that farmers in Jean Rabel ‘think’ occur, they ‘know’ they occur.” [iv]

Conclusion

Elsewhere, I showed that fertility rates in rural Haiti during the 1990s compare favorably with the highest rates ever recorded, those of the 19th and 20th century Hutterites. High fertility is achieved in spite of the presence of factors that should suppress fertility, including the absenteeism of men, free distribution of contraceptives by both government and private, nonprofit agencies, and common physiological factors such as STDs, the practice of prolonged lactation, and malnutrition. I linked high fertility in article ## to what I called rural Haiti’s pronatal sociocultural fertility complex. Both women and men exalt the blessings of having numerous children, caress and laud the pregnant, ridicule the childless, scorn contraceptives, and criminalize abortion. In this article I have shown that customs and beliefs in rural Haiti reinforce the pronatal sociocultural fertility complex: In spite of—or perhaps because of— male absenteeism and male poverty, men are encouraged to be sexually aggressive; women are rewarded and remunerated for sexual intercourse, while confining it to acceptable and financially capable fathers; conflict over infidelity and ambiguous paternity are rationalized with fictive illnesses and appeal to superstition and magic. These patterns of behavior are embedded in a flexible type of sexual-material negotiation between men and women, what other scholars have called “gendered capitalism” as well as part of a “field of competition” and that I referred to here as the sexual moral economy.

WORKS CITED

Coreil, Jeanine, Deborah L. Barnes-Josiah, Antoine Agustin, and Michel Cayemittes. 1996. Arrested pregnancy syndrome in Haiti: Findings from a national survey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, 10(3):424–36.

Duany, Jorge. 1984. Popular music in Puerto Rico: Toward an anthropology of “Salsa.” Latin American Music Review 5(2):186–216.

Lowenthal, Ira. 1987. Marriage is 20, children are 21: The cultural construction of conjugality in rural Haiti. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University.

———. 1984. Labor, sexuality and the conjugal contract. In Haiti: Today and tomorrow, ed. Charles R. Foster and Albert Valman. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Murray Gerald F. 1976. Women in perdition: Fertility control in Haiti. In Culture natality and family planning, ed. John Marshall and Steven Polgar, 59–79. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center.

Richman, Karen E. 2003. Miami money and the home gal. Anthropology and Humanism 27(2): 119–32.

Schwartz, Timothy T. 2012. Sex, Family & Fertility in Haiti. Create Space.

Szwed, John F. 1970. Afro-American musical adaptation. In Afro-American anthropology, ed. Norman F. Whitten and John F. Szwed. New York: Free Press.

Notes

[i]. The exception is if, when her spouse enters into a union with another woman, the first wife immediately severs the relationship. She then has a right to shamelessly enter into union with another man, but she has sacrificed the house built by the first husband; see Schwartz 2012: chapters 14–15.

[ii]. The figures are from the baseline subsample, n = 136, 68 women and 68 men. In the baseline sample (N = 1,586, missing = 146) the averages were 5.9 children per male household head interviewed (875) and 5.2 children per female household head interviewed (560).

[iii]. Credit for first reporting on perdisyon goes to Gerald Murray (1976), who convincingly explained the phenomenon as the only theologically appropriate approach to treating fertility because in Haiti the actual act of conception is entirely a matter for God (bon dieu) and, therefore, folk healers must first diagnosis a pregnancy before they can begin to treat the childless woman. When first reading Murray’s article as an undergraduate I was strongly tempted to extend his observation to explain perdisyon as a belief maintained and reinforced by women in union to justify pregnancy in the absence of their husbands, an especially appealing explanation as Haiti has a history of over one hundred years of male wage migration. And I do not argue with the notion that this may be one function that perpetuates the acceptance of the belief in perdisyon. Nor does Murray doubt this occurs (personal communication). In a discussion of the issue, anthropologist Ira Lowenthal affirmed that he knows at least six Haitian women, all in union with men who claim to have experienced perdisyon and all invoked the belief in the context of conception in their husband’s absence. I too have seen perdisyon used this way in at least one instance. In my own research, however, the primary function of perdisyon appears, as explained in the text, not to be a rationale for pregnancy but for barrenness. Women typically decide they are experiencing perdisyon before they are really pregnant and it is recognition of the condition at this stage that makes it authentic in the eyes of the woman’s family, friends, and lovers. The condition is from that point on used to tag the next child born to that particular man with whom she was having relations when perdisyon began.

In six of the eight cases of perdisyon reported in Makab, it was the woman’s first pregnancy, her husband had at least one other madam (wife), and she explained her perdisyon as being induced magically by one of her husband’s other wives. Treatment can get costly. It is understood that Western-trained medical doctors generally do not recognize or believe in the affliction, but there are medsin (herb doctors), matwons (midwives), manyè (massage specialists), and mambos and bokors (shaman) who specialize in helping women to overcome perdisyon and get the fetus growing again.

[iv]. Accusations of magic go both ways. Both men and women can go to the bokor for a magic spell or charm. A woman can jayjay—tame/brainwash/stupefy—a man with food cooked in water with which she has bathed her genitals or food that has been covered with an unwashed genital rag.