Researchers working in Haiti have long noted that rural parents were extremely pronatal. Both men and women hoped to have large families with many children.

Social scientists typically explained the trend with “love” and “prestige,” “absence of contraceptives,” and “tradition” (Herskovits 1937: 89); “the desire to live with reason, and to die with dignity” (Lowenthal 1987: 305); “fear of abandonment in women” (Maynard-Tucker 1996: 1387); rooted in the culture” (Ibid); old age security (Murray 1977); and even land redistribution mechanisms (Ibid). But no matter how they explained it, the one incontestable point was that peasants wanted many offspring. Children were considered desirable and a blessing.

However, there have long been factors that mitigate against high birth rates among the peasants. Specifically, high rates of infectious diseases, low-fat and low-calorie diets, high rates of female malnutrition, demanding work regimes, and a high rate of male absenteeism were all factors that weighed heavily against the likelihood of high birth rates.

Below I show that the unique social values associated with what I call Haiti’s “Pronatal Sociocultural Fertility Complex” reinforced by peculiar features of the rural Haitian “Sexual-Moral Economy” made high birth rates possible despite these afflictions.

To illustrate how, I look at data from Jean Rabel, a commune in Haiti where I conducted extensive research between 1990 and 2007, including a 1,586 household survey.

Jean Rabel vs. the Hutterites

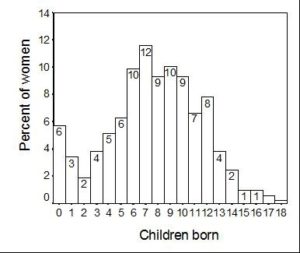

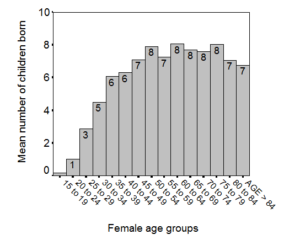

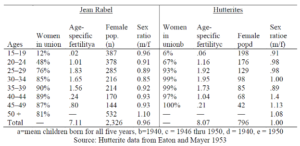

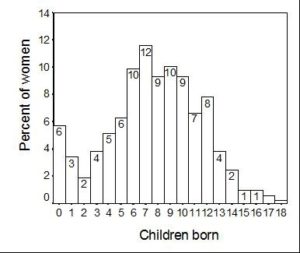

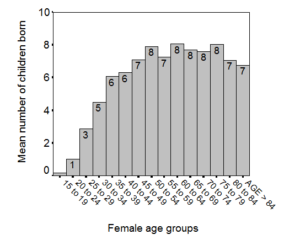

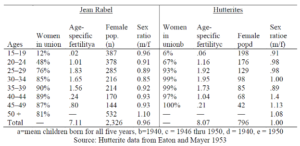

If Jean Rabel were a country, then at the time I carried out my research it would have had the second highest total fertility rate (TFR) in the world: 7.1 births per mother. The achievement is startling because in the endeavor to reproduce, Jean Rabel women face extreme adversity. High incidence of diseases, widespread malnutrition, intensive physical exertion and labor regimes, and the disruption of unions through male absenteeism should impede high fertility. Yet, Jean Rabel fertility rates measure up impressively to that of the early 20th century Hutterites, people who had the highest sustained fertility levels ever recorded. Thirty-two percent of Jean Rabel women equal or exceed the median ten births attained by early to mid 20th century Hutterite women (Eaton and Mayer 1953; Larsen and Vaupel 1993; Nonaka et al. 1994) [note 1].

Figure 1: Completed fertility in Jean Rabel for women over 45 yrs

Factors that Dampen Fertility

Data from the 1,586 household Survey mentioned above indicate that 5.7 percent of Jean Rabel women never succeed in carrying a pregnancy to full term, a figure close to the median of 4.2 percent reported for all developing countries (Vaessen 1984). Clinic records for pregnant women also indicate that, at any given time, 5 to 10 percent of women in the region suffer from sexually transmitted diseases such as chlamydia, HIV/AIDS, and syphilis—maladies that interrupt and sometimes prematurely end reproductive careers. As seen, other widespread and debilitating diseases such as malaria, typhoid, and hepatitis annually leave over 30 percent of women in the region bedridden and sexually incapacitated for months and sometimes years [note 2].

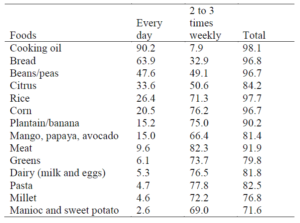

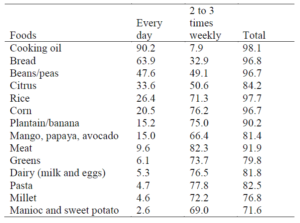

Malnutrition and high levels of physical exertion are also factors known to lower fertility by inducing amenorrhea—the suspension of menstrual cycles for three or more months. In the Baseline Survey, women were found to generally consume low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets (see table 4.1). And 26 percent of Jean Rabel women were found to be slightly to severely malnourished [note 3].

Table 1: Most commonly eaten foods in Jean Rabel (N=1,483)

The average Jean Rabel woman also leads a physically demanding life. Fetching household water requires daily walks to water sources often located more than one half hour from the household. The return trip involves carrying a filled five-gallon bucket balanced on top of the head. Women also walk an average of six hours per week to make market purchases and sales for the household.

Figure 2: Completed fertility in Jean Rabel for five-year age groups

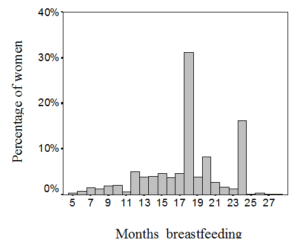

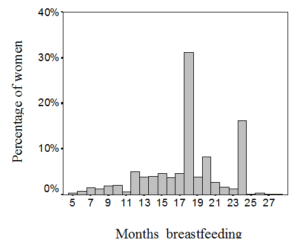

An average of six hours per week is also spent picking produce from the gardens, and another twelve to twenty-four hours are spent walking back and forth from the nearest water source to hand scrub clothes. This total exercise regime certainly matches or exceeds the five miles of jogging per week that induced amenorrhea in 6 percent of the U.S. subjects studied by Feight et al. (1978) and is probably closer to the weekly physical exertion of women in the same study who ran forty-five miles per week inducing amenorrhea in 43 percent of the cases. Extended breastfeeding, necessary in the absence of high-protein baby formulas, is also known to suppress ovulation (WHO 1999); and 63 percent of women in the Jean Rabel Baseline Survey reported breast feeding their last child for eighteen to twenty-seven months [note 4].

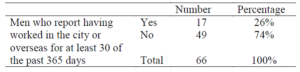

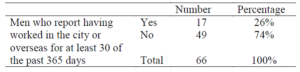

Figure 3: Duration of breastfeeding

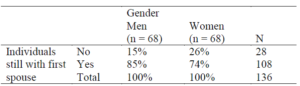

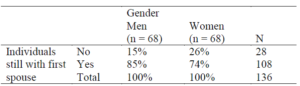

Another factor researchers have identified as a determinant of low fertility is reduced exposure to the risk of pregnancy through late entry into union or disrupted union through factors such as wage migration (Bongaarts and Potter 1983; Williams et al. 1975; Blake 1954). Male absenteeism is part of the rural Haitian demographic profile. Males in Haiti migrate to larger Haitian cities and overseas to the Bahamas, the United States, and the Dominican Republic at a significantly higher rate than their female counterparts. The result is lower male-to-female sex ratios. In the Baseline Survey, 10 percent of Jean Rabel men in the twenty- to forty-nine-year-old age groups were reported as being absent and no longer considered as members of the household from which they originated. Furthermore, in the Opinion Survey, 26 percent of men in union reported having been away from home for at least 30 of the preceding 365 days (see table 3). Congruent with male transience, 52 percent of Jean Rabel women in the twenty- to twenty-four-year-old age group and 26 percent of women in the twenty-five to twenty-nine-year-old age group were not in union at the time of the interview,,, and at least 26 percent of women abandon or are abandoned by their first spouse during the course of their reproductive careers (see table 2).

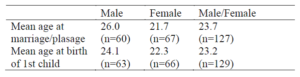

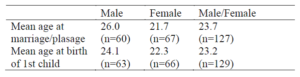

In a society with strongly enforced values regarding monogamy and premarital pregnancy, the type of male absenteeism and transience being described would disrupt ongoing conjugal union and force a minority of women to remain out of union and childless. Yet, according to respondents in the Opinion Survey, the average age at first union for Jean Rabel women is 21.7 years and the average age at first childbirth is 22.3 years. These averages for Jean Rabel women are not unusually high or low. For example, the average age women in the remote rural Dominican Republic first enter into unions and give birth is significantly lower than the averages cited for Jean Rabel (McPherson and Schwartz 2001). Nevertheless, entry into union at moderate age and the high birth rates are accomplished despite high rates of male absenteeism.

Table 2: Mean age of follow-up survey respondents

Table 3: Temporary male migration in Jean Rabel

Table 4: Individuals still with first spouse

Jean Rabel Women vs. Hutterite Women

Despite all the preceding factors that work against high fertility, Jean Rabel women measure up impressively against the Hutterites of North Dakota and Canada, the healthy, well-fed, and fecund world champions of high fertility. Jean Rabel women on average eat two and sometimes only one cooked meal per day and meals rarely include meat or dairy foods (see table 1). Hutterite women eat three meals per day, every day, and meat, dairy products, or sometimes both are included in virtually every meal (Hostetler 1974: 353). Further, while Jean Rabel women are members of what is among the most disease-ridden populations in the Western hemisphere and at any given time upwards of 5 percent of Jean Rabel women are suffering from an STD—to say nothing of other infectious diseases—the incidence of infectious diseases among Hutterites is even lower than their healthy Canadian neighbors, something that Ross and Cheang (1997) attribute to a genetically superior immune system. When Eaton and Mayer (1953) surveyed the Hutterites during the 1940s they found virtually no deprivation or interruption of Hutterite unions resulting from imbalanced sex ratios, wage-migration, or divorce. There were 106 men for every 100 women in the twenty- to forty-nine-year-old age range. Only 33 percent of Hutterite women in the twenty- to twenty-four-year-old range were not in union; and only 7 percent of those in the twenty-five- to thirty-year-old age group were not in union. In comparison, 52 percent and 26 percent of Jean Rabel women in the same age groups were not in union (see table 5, following page). Eaton and Mayer (1953) noted that:

Hutterite couples are never separated after marriage. In the history of the group since 1875 there has been only one divorce and only 4 desertions. We know of one other case where husband and wife separated temporarily to live in different colonies. (p. 223)

Thus, while reproductive-age Jean Rabel women are faced with a 10 percent deficit of men, Hutterite women are outnumbered by men. And, as might be expected, there was an average of 13 percent more reproductive-age Hutterite women in union than there are in contemporary Jean Rabel [Note 5, 6].

But despite all of the limiting factors, including the absence of many Jean Rabel men and the physiological factors mitigating against high fertility, 32 percent of contemporary Jean Rabel women who have completed their childbearing careers equal or exceed the median ten children born per Hutterite woman in the years 1880 to 1950. Contemporary Jean Rabel fertility levels are 13 percent higher than contemporary Hutterites (Eaton and Mayer 1953; Larsen and Vaupel 1993; Nonaka et al. 1994) [Note 7].

Table 5: Hutterites vs. Jean Rabeliens: Percentage of women in union per five-year age group and sex ratios (includes widows)

WORKS CITED

Bastien Remy 1961 “Haitian Rural Family Organization” In Social and Economic Studies 10(4):478-510.

Bell, Beverly, 2001 Walking on Fire. Cornell University Press

Blake, Judith. 1954. Family instability and reproductive behavior in Jamaica. Milbank Memorial Annual Conference:26–61.

Bongaarts and Potter 1983

CARE 1996 A Baseline Study of Livelihood Security in Northwest Haiti The Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology. University of Arizona. Tucson, Arizona.

CARE 1997 An Update of Household Livelihood Security in Northwest Haiti Monitoring Targeting Impact Evaluation/Unit December.

CIA 2010 World Fact Book.

Coreil, Jeanine, Deborah L. Barnes-Josiah, Antoine Agustin, and Michel Cayemittes. 1996. Arrested pregnancy syndrome in Haiti: Findings from a national survey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, 10(3):424–36.

Correil, Jeannine, Deborah L. Barnes-Josiah, Antoine Agustin, Michel Cayemites 1996 Arrested Prenancy Syndrome in Haiti : Findings from a National Survey Medical Anthropology Quarterly. New Series; 10(3):424-426.

Courlander, Harold, 1960 The Hoe and the Drum: Life and Lore of the Haitian People. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Divinski, Randy, Rachel Hecksher and Jonathan Woodbridge (eds.) 1998 Haitian Women: Life on the Front Lines PBI (Peace Brigades International)

Duany, Jorge 1984 Popular Music in Puerto Rico: Toward and Anthropology of “Salsa” Latin American Music Review 5(2):186-216

Eaton, Joseph W., and Albert J. Mayer. 1953. The social biology of very high fertility among the Hutterites: The demography of a unique population. Human Biology, 25:206–64.

Ember, Melvin. 1974 Warfare, sex ratio, and polygyny. Ethnology, 13, 197-206.

Feight, C. B., T. S. Johnson, B. J. Martin, K. E. Sparkes, and W. W. Wagner. 1978. Secondary amenorrhea in athletes. Lancet 2:1145–46.

Francis, Donette A. 2004 “Silences Too Horrific to Disturb”: Writing Sexual Histories in Edwidge Danticat’s Breath, Eyes, Memory” Research in African Literatures – Volume 35, Number 2, Summer, pp. 75-90 Indiana University Press

Fuller, Anne 2005 Challenging Violence: Haitian Women Unite Women’s Rights and Human Rights Special Bulletin on Women and War. ACAS website: http://acas.prairienet.org. accessed 10-19-2006. Originally published in the Spring/Summer 1999 by the Association of Concerned Africa Scholars.

Herskovits, Melville J. 1937 Life in a Haitian Valley. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hostetler, John A. 1974. Hutterite society. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Scott, James C. 1976 The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia. Yale University Press

Larsen Ula, and James W. Vaupel. 1993. Hutterite fecundability by age and parity strategies for fertility modeling of event histories. Demography 30(1):22.

Leyburn, James G. 1966 (originally 1941) The Haitian People. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lowenthal, Ira 1987 Marriage is 20, Children are 21: The Cultural Construction of Conjugality in Rural Haiti Dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University. Baltimore Maryland.

Maynard-Tucker, G. 1996. Unions, fertility, and the quest for survival. Social Science & Medicine 43(9):1379–87.

McPherson, Matthew and Timothy Schwartz. 2001. The Defeminization of the Dominican Hinterlands: Conservation Implications for the Cordillera Central. The

Nature Conservancy: Arlington, Virginia.

Moral, Paul 1961 Le Paysan Haitien. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose.

Murray Gerald F. 1977. The evolution of Haitian peasant land tenure: Agrarian adaptation to population growth. Dissertation, Columbia University

Murray Gerald F. 1976. Women in perdition: Fertility control in Haiti. In Culture natality and family planning, ed. John Marshall and Steven Polgar, 59–79. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center

Murray, Gerald 1976 “Women in Perdition: Ritual Fertility Control in Haiti” In Culture, Natality, and Family Planning, eds. John F. Marshall, Steven Polgar, Chapel Hill: University of Florida.

Murray, Gerald, Matthew McPherson, and Timothy T. Schwartz. 1998. Fading frontier: An anthropological analysis of social and economic relations on the Dominican and Haitian Border. Report for USAID (Dom Repub)

N’zengou-Tayo M.-J. 1998 ‘Fanm Se Poto Mitan : Haitian Woman, The Pillar Of Society (Fanm Se Poto Mitan : La Femme Haïtienne, Pilier De La Société Centre For Gender And Development Studies, University Of The West Indies, Mona, Jamaique

NCHS 2010. Estimates of the April 1, 2010, July 1, 2010–July 1, 2012 United States resident population from the Vintage 2012 postcensal series by year, county, age, sex, bridged race, and Hispanic origin

Nonaka, K., T. Miura, and K. Peter. 1994. Recent fertility decline in Dariusleut Hutterites: An extension of Eaton and Mayer’s Hutterite fertility study. Human Biology 66(3):411–21

Richman, Karen E.

2003 “Miami Money and the Home Gal” Anthropology and Humanism 27(2): 119 -132

Ross R. T., and M. Cheang. 1997. Common infectious diseases in a population with low multiple sclerosis and varicella occurrence. Journal of Epidemiology 50(3):337–39.

Schwartz, Timothy 2007 Subsistence Songs: Haitian Téat Performances, Gendered Capital, and Livelihood Strategies in Jean Makout, Haiti. New West Indian Guide. Vol. 81, No. 1/2 (2007), pp. 5-35.

Schwartz, Timothy 2004 “’Children are the Wealth of the Poor’: Pronatalism and the Economic Utility of Children in Jean Rabel, Haiti.” In Research in Economic Anthropology. Volume 22:61-105

Schwartz, Timothy 2000 “Children are the Wealth of the Poor:” High Fertility and the Organization of Labor in the Rural Economy of Jean Rabel, Haiti (PhD dissertation). Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida.

Schwartz, Timothy T. 2009 Fewer Men, More Babies: Sex, family and fertility in Haiti. Lexington Press. USA

Simpson, George Eaton 1942 Sexual and Family Institutions in Northern, Haiti. American Anthropologist 44:655-674.

Szwed, John F. 1970 “Afro-American Musical Adaptation” In Afro-American Anthropology, edited by Norman F. Whitten and John F. Szwed. New York : Free Press

UNDP 2018. Evidence-based Human Development: Measuring the opportunity cost of teenage pregnancy in the Dominican Republic.

UNICEF 2006. Fertility and contraceptive use: Global database on contraceptive prevalence.

UNICEF 2008. Country Statistics.

UNIFEM 2006 UNIFEM in Haiti: Supporting Gender Justice, Development and Peace UNIFEM Caribbean Office Christ Church Barbados Accessed October 18th 2006

United Nations Development Programme 2006 Human Development Indicators 2003

UNOPS 1997 Ministère de la Planification et de la Coopération Externe (MPCE) Direccion Departmental du Nord-Ouest July) Éléments de la Problématique Déparetmentale (Version de Consultation) Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement (PNUD), Centre des Nations Unies pour les Établissements Humains (CNUEH-Habitat), Projet d’Appui Institutionnel en Aménagement du Territoire (HAI-94-016)

Vaessen, Martin. 1984. Childlessness and infecundity. Comparative Studies no. 31. Voorburg, Netherlands: International Statistical Institute.

WHO (World Health Organization). 1999. World Health Organization multinational study of breastfeeding and lactational amennorhea pregnancy and breastfeeding: World Health Organization task force on methods for the natural regulation of fertility III. In Sterility and Fertility 72(3):431–40.

Williams, S. J., N. Murthy, and G. Berggren. 1975. Conjugal unions among rural Haitian women. Journal of Marriage and the Family 4:1022–31.

World Bank 2002 A review of Gender Issues in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica. Report No. 21866-LAC. December 11th , Caribbean Management Unit, Latin America and the Caribbean Region.