Here I review the history of humanitarian aid beneficiary targeting in Haiti. I begin in the 1950s and 1960s with the Community councils, move through the 1970s and 1980s looking at gwoupman and the liberation theology movement. Very importantly I show how the revolutionary Liberation Theology movement of the 1970s to 1990s that were intended to break the repressive rural patron/client structure was defeated. But it nevertheless led to a massive exodus of the rural elite and gave way to conditions that are arguably more of an impediment to improving rural living standards than what existed. Specifically, the struggles of the 1980s and 1990s left a leadership vacuum in rural areas. In its place came a system of aid entrepreneurism oriented toward capturing any assistance from the outside and diverting it back to urban areas or overseas.

Community Councils (1950s to 1980s)

In 1963, as then president Francois (“Papa Doc”) Duvalier was consolidating his power and turning himself into a dictator, he made a national policy of “integrating rural communities into the rhythm of national progress.” To accomplish this, he chose as the official mechanisms for rural development the Community Councils, then called in French, Conseils d’Action Communautaire, or in Kreyol, Konsey Kominote. These were community action councils reputedly inspired by the French “animation rurale”.

Papa Doc has been demonized in most of the literature as a tyrant and sociopath, but at the time he was working hand in hand with the objectives of international donors and NGOs, which had already begun using Conseils Communitaires in earnest during the 1950s. The Councils were, in practice, identical to Community Based Targeting Strategies of today. They had selected representatives of sectors of the community and elected officials. They dealt with all areas of development: disaster relief, soil conservation, health, road rehabilitation, irrigation as well as agriculture and livestock extension services. They used Food-for-Work as a principle tool. But going farther than current CBT, the Community Councils of the 1960s, and 1970s operated at the below the level of Commune Section and made community support and participation a criteria for receiving aid. Specifically, communities were required to contribute 50% of Cash-for-Work projects. When Papa Doc declared them part of national development policy, USAID (1983) commended the move to community councils as, “A guided self-help process” that responded to the USAID grant objective, “to develop self-sustaining community action programs” (Ibid).

By the mid to late 1970s there were 212 councils in Department of the North West Haiti alone (one of the Haitis then nine Departments). A 1983 USAID evaluation found that the Community Councils “were effective in distributing aid and reaching people.” In the case of HACHO in the NW, the councils were a critical guiding component in a USAID funded parastatal venture managed jointly by the Government of Haiti and CARE International. A strength of the strategy was that it plugged into the existing rural hierarchy of gran don and gran dam–large and powerful landowners– and while there were complaints about large landowners re-directing Food-for-Work to their own properties, even the criticisms suggest that the intended work was being accomplished and aid reached the poor (USAID 1983; Lavelle 2010).

Nevertheless, although heralded as greatly successful during the 1960s and early 1970s, by the 1980s most consultants, academics, evaluators, and even NGO workers viewed the Community Councils as detrimentally linked to rural and urban elites; as extractive, exploitative, and out of synchrony with the rural population. Maguire (1979: 28) wrote that, “The gravest problem with the community councils is that their leadership… tends to come from the local gros neg.” Honorat wrote that they “became ‘citified’” and “too often developed enduring and sympathetic ties to individual locales,” and that they tended to become, “clusters of people waiting to receive and control some development project benefit” (cited in McClure 1984: 5; see also Smucker 1982, 1984).

The change in attitude toward rural community councils coincided with political changes. More specifically, with the passing of the populist Francois (“Papa Doc”) Duvalier regime, a shift occurred between 1971– the date of the dictator’s death–and 1981, the date when Jean Claude (Baby Doc) Duvalier administration fully assumed control of the government.[i] In 1981, fed-up with corruption, USAID redirected aid from the government and began delivering foreign aid directly to NGOs (Lawless 1986). The Jean Claude Duvalier Government tried to keep control of the money by with a decree that gave the National government more control over Community Councils, the primary aid Targeting Mechanism that the NGOs were still using to deliver aid (Smucker, 1986, p. 104). NGOs turned to gwoupman.

Gwoupman (1970s to 1990s)

Gwoupman emerged during the 1970s as a bottom-up challenge to the Community Councils. They were smaller than Community Councils, composed of from a few to a dozen peasant producers, typically excluded government officials, town elite, and the large landowners found on the councils above. They were first formed as part of the Catholic Liberation Theology movement, but secular NGOs also promoted the gwoupman strategy (Zaag 1999).

The gwoupman strategy seemed specifically designed to bypass the Community Councils: it was not hierarchical, did not include elites of government officials, and was highly participatory and effective at mobilizing the poorest people in rural areas. Its strengths were that it mimicked the informal friend and neighbor based supra-households structures that Haitian farmers are familiar with, specifically, reciprocal labor groups (eskwad), rotating savings groups (sol or sang), and religious musical groups (societé). With support from NGOs, USAID and other donor, by the late 1980s gwoupman had supplanted Community Councils as the dominant Beneficiary Selection Strategy.

But gwoupman were not simply a development strategy. Whatever the original intentions, many became part of a revolutionary movement, Lavalas (the Flash Flood or Avalanche), that was promising to radically change Haiti, creating massive political participation from the poor. Instrumental in the fall of the urban oriented Jean Claude Duvalier regime, a struggle between the elite dominated Community Councils and the now hegemonic, gwoupman occurred throughout the Haitian countryside. On at least one occasion, that of Jean Rabel, 1987, open warfare broke out between gwoupman and those who were leaders of the Counseil Communitaires. In that particular instance the gwoupman were decimated, with an official 127 killed. But although repressed at times, the gwoupman were a major force in subsequently bringing the Aristide administration to power in 1991 (Lundhal 2013: 122), after which most Community Councils ceased to exist (Lundahl 2013:122). It was at that point that gwoupman experienced what Smucker and White (1998) call an ‘exuberant explosion’ in numbers.

In another radical twist of fate, a coup d’etat followed seven months after Aristide took power, and with the subsequent 1991-1994 military junta came a backlash against Aristide supporters, not least of all the rural gwoupman. As White and Smucker (1998) recount, “their leaders went into hiding or to their graves.” The gwoupman movement then, like the Community Councils, disappeared

Associations (1990s to Present)

When the international community helped return Aristide return to power in 1994, aid donors and implementing partners once again changed strategies. Aristide had returned, yes, but on a very tight lease held by the international donor community. There would be no more Liberation Theology movements. Gwoupman was now a term stained as denoting left wing rural political parties. Donor money earmarked for development now went to International NGOs. The NGOs in turn depended more on organizing, training, and supporting their own networks of “barefoot” community health, veterinary, agricultural, and disaster-risk extension agents who interfaced either directly with farmers or the corporate-like associations we still see today. First, I’ll talk about the Association.

The Association—or in Kreyol asosyasyon, oganizayon or mouvman—is an institutional descendent of the “cooperatives” that had been promoted in Haiti since the US Marine Corps occupation (1915-1934). During the Community Councils heyday of the 1960s and 70s, they had been intermediary beneficiary units, meaning that Community Councils passed aid to Associations, made up of a membership of impoverished farmers, and those Associations were intended to distribute it to the intended farmers or cash-for-work and food-for-work participants. “Associations” are larger than the gwoupman and hierarchical like the Community Councils. The most significant difference between an Association and the earlier gwoupman is that they must register with the State to be recognized and they must swear off political agendas, a backlash to the political activism of the gwoupman. Some of the major associations found in the 1990s and even today are actually federations of gwoupman from the 1980s.

Contemporary lists contained in Development Plans for Haitian communes suggest that there are at least 1,500 CBOs in rural Haiti. These include associations for women, youth, social assistance organizations, and handicap cooperatives. With their formal structure, charters, mandate and tiered positions, they resemble the formal extension organizations seen below, but their membership is comprised of potential beneficiaries, and what can be defined as “organic,” “self-selected,” or as defined here, “bottom-up” participants. In principle they are member-governed and leaders reside in their areas of operation and are thus subject to community censure and can be thought of as bottom up organizations.

In practice, however, many associations differ little from the extension targeting organizations described below. They have reputations for graft and corruption. Kaufman observed that associations, women’s clubs and other community groups that had survived or emerged after the fall of the national gwoupman movement, “frequently are formed in response to community development programs and remain, to a significant extent, ‘groups of symbolic participation’” (Kaufman, 1996, p. 10). Jennie Smith as “…plagued with corruption, mismanagement and other problems.” Despite the expectation that they are bottom-up, in many cases those who control the associations do not live in the areas fulltime or move after they get control of the finances, maintaining enough of a presence support comfortable lifestyles for themselves or their families in the provincial city, Port-au-Prince or overseas. Notwithstanding, associations together with churches are those extension targeting organizational strategies most favored by beneficiaries (see this report), suggesting that they may indeed be more reliable in reaching beneficiaries than their professionalized counterparts

Extension Agents (Present)

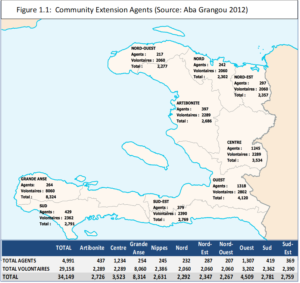

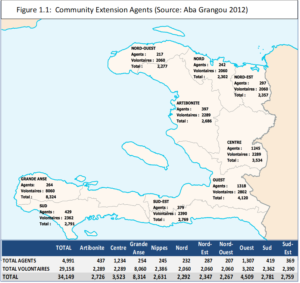

Extension Targeting are today the most widely used Targeting strategy in Haiti. In 2012 Aba Grangou conducted a census of top-down community extension networks in Haiti and counted a total of 28 programs employing 35,149 professional and volunteer agents located throughout the country. Thirty (30) of the 38 programs were health related. Some have been operant in Haiti for decades, as with Hospital Albert Schweitzer (1956) on the Artibonite and Haiti Health Foundation (1989) in the Grand Anse. But the extent of these resources should not be overestimated. Of the 17,149 health agents, 6,000 are members of the USAID funded Haitian Health Foundation in the Grand Anse. Others are also concentrated in specific areas. Moreover, the greatest absolute number of Top-Down Extension agents are associated with emergency response. Just two of them–the Haitian Red Cross (12,000 volunteers) and Haitian Civilian Protection DPC (7,000)–account for more than 53% of all extension agents in the country.

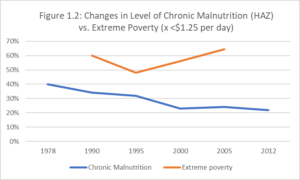

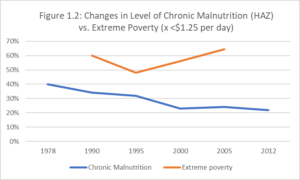

Regarding the effectiveness of top-down extension agents, health workers appear to be the most effective. They already target people in the communities and their criteria is unimpeachable: injury, illness and malnutrition. Success at the national level can be inferred from declining malnutrition in face of stagnant and even intensifying income levels (see CNSA Report). However, they have been used extensively in past targeting and deliveries of aid to vulnerable households and there is widespread agreement that their involvement distracts from their health targeting mission.

Non-health targeting agents are problematic in other ways. While it may be politically inexpedient to acknowledge the extent to which the aid process has been corrupted, the majority or people who read this report know very well that the most significant challenge to effective targeting is corruption and the lack of accountability that nurtures it, i.e. weak monitoring and weak systems of sanctions. The modern epoch of foreign emergency aid to Haiti began with the devastation of Hurricane Hazel in 1954 when the international community and NGOs poured assistance into the country. The associated corruption was such that US diplomats and Marine historians Heinl and Heinl (1978), recall that wealthy women in Port-au-Prince who had benefitted from the “aid” subsequently dubbed their new mink stoles “Hazels.” For 50 years now, most evaluation reports end recommending that Monitoring and Evaluation be reinforced. This is true whether discussing NGO extension services or larger volunteer networks. But Haitian monitors who make ambitious inquiries and question the validity of target lists often encounter non-cooperation and cover-up. For foreigners the density of Haitian social networks and the inscrutability of the culture makes investigation nearly impossible. It is not expedient to here recount the details or name individual NGO programs and International agencies, but those past investigations that have extended beyond the office and inventory lists have frequently resulted in programs being shut down and staff transferred or dismissed. To assume that extensive fraud at the level of targeting is not occurring today is to bury our heads in the sand. Not only do beneficiaries vociferously complain about corruption in top-down programs, I’ve listened ad naseum to program directors and staff speaking candidly about school feeding programs that do not feed, beneficiary lists stuffed with false names, and beneficiaries who must pay to participate in programs (see Travesty in Haiti or better yet, Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle). In the wake of the 2010 earthquake and flood of aid money, there were arguably more, far more programs where tens of millions of dollars disappeared into rural areas with no for material results, indeed, barely a trace than there were that had a demonstrable impact. Most of this corruption occurred/s at the high levels of administration but in defense of the those at lower levels, many volunteers and most midlevel employees might otherwise qualify as beneficiaries themselves, or at least have extensive family and friends who should qualify, putting a great deal of pressure on them to select family and friends as beneficiaries.

What exists today is a mixture of the strategies discussed above…. The avant garde NGOs and International organizations use CBT; health organizations and some NGOs still using the traditional networking (barefoot animators); networks of Red Cross Volunteers, Scouts, and the para-statal Civil Protection use network targeting and surveys (so they claim)–all are, in theory, volunteers, however, many make more in per diems when they ‘volunteer’ (400 to 500 goud or USD $8 to $10) than the average vulnerable beneficiary earns in a week of agricultural labor.

Churches (… to Present)

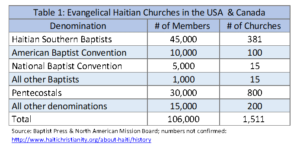

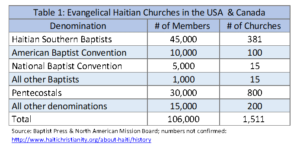

Small Catholic churches and multitudes of evangelical churches are left out of the Aba Grangou calculations of volunteer networks seen above and typically only tangentially involved in State and international targeting strategies. Yet, from the perspective of beneficiaries they are the most important extra-household organization in Haiti. Based on studies elsewhere, less than 20% of the adult population is a member of an association or NGO extension service of any kind; but more than 50% report being members of a Christian church (CARE 2013; LTL 2011). A much as 70% of primary schools are associated with Christian churches (Sali 2000). Even if we only consider overseas sponsored Evangelical churches, with three times as many members as the formal Top Down networks seen earlier they dwarf secular extension networks in Haiti (see Table 1). Some churches have elements of being top-town by virtue of overseas funding for schools, clinics and the founding of churches as well as the presences of resident missionaries from other countries and frequent and intense involvement of visiting “teams” of volunteers from overseas congregations. But all the churches have community membership based on self-selection and in many cases with no material inducements. At least part of the leadership is entrenched in the community to an extent rivaled only by the associations. Many are also linked to the community through schools, clinics, and Health Extension organizations seen earlier.

Community Based Targeting and the New Community Councils (2014 to Present)

No review of humanitarian aid targeting in Haiti can be complete without a discussion of more recent Community Based Targeting campaigns. In 2004, following 2 years of an aid embargo and the subsequent fall of the second Aristide Administration, there came yet another change in Targeting strategies, a shift to increased inclusion of para-statal institutions that function almost exactly as NGOs and a return to the Community Councils. The new terms that came with the change was “Community Based Targeting.” The World Bank launched the $61-million dollar PRODEP (Project for Participatory Community Development) and implemented in Haiti its new version of Community development, Community Driven Development, at the center of which were the Community Based Targeting and the new Community Councils. NGOs such as Oxfam, and International Organizations such as WFP, and new parastatal organizations (and para-NGOs), such as FAES, also made Community Based Targeting– with the formation of hierarchical committee, elected officers–the standard.

It is difficult to discern the difference between contemporary “Community Demand Driven” development of today (CDD) and “Community Based Development” (CBD) by which scholars of Targeting studies define the Community Councils of the 1960s and 1970s. The modern CDD and its accompanying Community Based Targeting purported to use a formal process that included community involvement at every stage of the development process including, at its fullest extent, control over funds. But with regard to targeting the most vulnerable the issue of control over food or funds is usually moot. Community Councils in the early 2000s and today are indistinguishable from those of the 1960s and 70s. Just as today, council members were selected from representatives of different sectors of the community (government, religious, NGO, business…). The process also included democratic election of officers. Descriptions of the objectives and claims from contemporary proponents of CBT could just as well come from their counterparts in 1960s and 1970s such as the claim that, “CADEPs have become the representative organizations of civil society in local municipalities”.

Putting it All Together: Effectiveness of Past Targeting Strategies in Haiti

In looking back at the effectiveness of the varying targeting strategies since the 1980s the one consistency is the content of the critiques. Smucker concluded about the Community Councils and the associations that worked with them (also at the time called ‘konsey’) that,

They became projectoriented and widespread perception was that they became dependent on the Food and tried to capture it… Also much complaining, even then, about the implications of foreign surplus. (White and Smucker, 1986, p. 109).

What Smucker found in the 1980s was applicable in the 1990s, when Kaufman concluded that gwoupman, community associations, women’s clubs and other community groups “frequently are formed in response to community development programs and remain, to a significant extent, ‘groups of symbolic participation’” (Kaufman, 1996, p. 10).

Jennie Smith summed up what most aid workers feel today when she wrote in 2001 that what she called “community action groups” –i.e. associations– can mobilize people, but are “…plagued with corruption, mismanagement and other problems.”

In explaining the effectiveness of the bottom-up community-based organizations, we need only draw on what White and Smucker said 16 years ago, something that could have just as well been written today:

Nepotism and unmitigated loyalty to extended family and individual factions have a long history in Haiti -most notably in their effect of undermining the effectiveness of formal institutions and democratic initiatives. (White and Smucker, 1986, p. 4)

In White and Smucker’s comprehensive review of the topic, explanations for the failure of CBOs as effective Targeting mechanisms can be seen the same factors that make the household itself the primary social security net,

…the traditional peasant practice [is one] of maintaining a low profile, avoiding the apparatus of state, and establishing furtive agricultural units on the margins of society. In the absence of community structures, the basic building blocks of rural social life are the peasant household unit, extended family ties, and the lakou – the house-and-yard complex… (White and Smucker, 1986, p. 2)

In summary, White and Smucker described 16 years ago precisely the situation we see today. Haitian rural subsistence strategies and associated value systems are anathema to those upon which Community Targeting and Community Based/Driven Development depends, but with one caveat: Community Councils seem to fit the description of what should be the most effective and natural form of Community Development and Targeting in rural Haiti. They reflect the traditional vertically stratified patron-client social structure that prevailed throughout the country and has since before independence, and they tap the few extra-households organizations that exist and are capable of being tapped for targeting and distribution of humanitarian aid—i.e. Church, asosyasyon, and political party. But the Community Councils working in the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s were written off in the late 1970s and early 1980s for having evolved into schemes to siphon off aid money. A concurrent trend, and possibly part of the reason for the change, was the massive exodus of the higher echelons of the rural classes. Understanding this exodus and the impact on the rural social structure should be considered a critical part of deciding how to target the most vulnerable in rural areas today.

The Difference Today: Migration

In the 1960s and 1970s the typical gran neg or gran dam was an individual belonging to a large family that, a) had more and better land than most people in the region, b) a better education, c) urban connections, but, d) was heavily invested in land, agricultural production, livestock rearing and, perhaps more than anything else, the aggregation and processing of local produce destined for export, typically coffee, cacao, rum, sisal, aloe, goat skins, and castor oil. As seen in White and Smucker’s comments in the previous section, they also made, like most of their constituents in rural Haiti, e) heavy investments in social capital. All had extensive networks of kliyan, people who were dependent on them for credit, as purchasers of their produce, and for sharecropping arrangements that brokered access to land and animals. All had many godchildren, and while some were pious Catholics, it was not uncommon for the wealthier men among them to have 20 or more recognized offspring. These economic patwon/kliyan relations, and fictive kinship relations, were expanded exponentially through the similar relations of their own siblings. It would have been rare during the 1960s to find an individual in rural Haiti who could not trace some kinship relationship to a local leader. Today these leaders are typically remembered as honest notables who would judge local disputes, whose decisions were respected, who were above reproach and who not only dominated the Community Councils, but whose presence and consent was indispensable in the acceptance of any community decision.

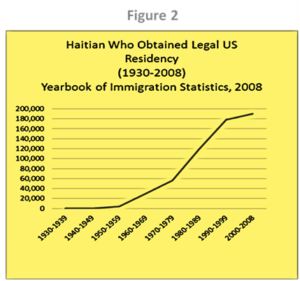

The extent of the romanticism of the notab of yesteryear recorded during the course of fieldwork is in stark contrast with those of today. Today the wealthiest people in any given rural area are typically described as volé (thief), showy (gen byen/pran poz), not invested in the local economy and not interested in community well-being or development. Although some of this discrepancy in notab of the past vs those of the present may indeed be written off to romanticism, the shift fits with the changing criticisms of the effectiveness of the Community Councils described earlier, i.e. that they are not invested in the local economy but rather siphoning off aid and money meant for community services and investment in infrastructure. The criticisms also coincide with changing national political and demographic trends. Indeed, if we look at these changes in the political, economic and demographic factors we should expect a disconnection between the wealthiest members of the community and the vulnerable masses: if for no other reason than, beginning in the 1970s, almost all of the members of the traditional rural elite left.

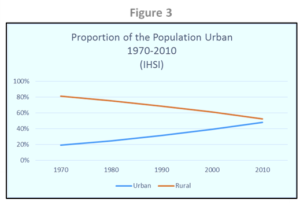

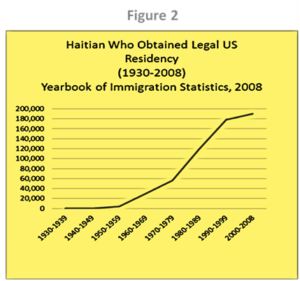

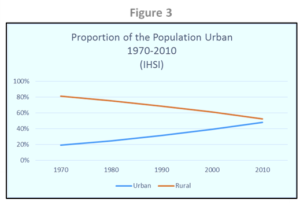

With the political turmoil seen earlier, the collapse of the formal economy and exports, the economic and social rural leaders increasingly invested, not in the local economy, but in getting themselves and their children out of the region (see Figures 3 & 4). The extent of the exodus and the shift in the economic leadership base from local economy to charity cannot be gainsaid. The Far-West, during the 1990s, is an example. Taking eight community leaders living in the region in 1990 (when I conducted my doctoral research in the area), they had 44 children over the age of 18 years: not a single one had remained in the area. 19 were living in Port-au-Prince; 25 were in the US and Canada (see Schwartz 1991).

The shift also had an economic dimension. Investment in out-migration created an economic vacuum. As elsewhere in Haiti, enterprises that thrived in the Far-West up through the 1980s collapsed in the 1990s. By 1996 rum, sisal, coffee, goat skins, aloe, and castor oil were no longer aggregated in significant quantities to justify exportation. Into the void came missionaries, orphanages, schools, churches and NGOs, all of which had–and still have–their economic base in donations from overseas. During the 1990s–and largely true today–all clinics, hospitals, road construction, irrigation, soil conservation, and schools—even the public Liceys (high schools)—were heavily dependent on missionaries, UN agencies, and overseas-based NGOs. This is true whether or not they were in name owned, constructed or maintained by the Haitian State. Consequently, for the majority of the rural population far and away the single most lucrative entrepreneurial opportunity became gaining access to those entities responsible for vectoring overseas aid. Whether for selfish or altruistic motivations, be it preacher, priest, orphanage owner, clinic owner, association director or those few non-charity endeavors such as merchant, shipowner, landowner, or politician, the major stakeholders earning money in rural Haiti and who were determined to keep a stake there moved his or her family to Port-au-Prince, Florida, New York, Boston, Montreal or Toronto while keeping an economic base in rural Haitian industry of charity. What they did with the money they earned or embezzled is just as important. Although they may have derived profits from their participation in regional overseas-funded charity and development enterprise, they overwhelmingly made their own personal investments in the safer, more stable, insurable and profitable external economies. They opened bank accounts in the US and Canada, bought homes and businesses there, and sent their children to school there. Moreover, while most observers prefer to ignore the topic, the situation was aggravated by the concurrent and very real emergence of illicit drug trafficking as the industry of choice for what has become provincial and arguably even metropolitan Haiti’s most powerful elite, even more powerful than the new custodians of charity. What all this has meant for prospects of Community Based Targeting is that a sense of community responsibility and community censure has been sapped, leaving little reason to expect anything different than the fraud, corruption, and nepotism that evaluators, scholars and NGO workers seen in the previous section began describing in the 1980s—the same time period for which out-migration became the major demographic trend. But perhaps more importantly than anything else, among the poor who are left behind, what remained of particular survival strategies they depended on for the past 200 years allegiance to household and family and values, loyalties that are anathema to the impartial participation in targeting and aid distribution that the State, NGOs and International organizations purport as idealize.

Bibliography

Aba Grangou 2012 Unpublished

ALNAP. 2012 Responding To Urban Disasters: Learning From Previous Relief And Recovery Operations November www.alnap.org/resources/lessons.

Bastien, Remy. 1961. Haitian rural family organization. Social and Economic Studies 10(4):478–510.

Berggren, Gretchen, Nirmala Murthy, and Stephen J Williams. 1974. Rural Haitian women: An analysis of fertility rates. Social Biology 21:368–78.

Borgatti, S.P. 1992. ANTHROPAC 4.0 Methods Guide. Columbia: Analytic Technologies.

CARE 2013a The Kore Lavi Program (United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance Office of Food for Peace

CARE 2013b Gender Survey CARE HAITI HEALTH SECTOR Life Saving Interventions for Women and Girl in Haiti Conducted in Communes of Leogane and Carrefour, Haiti

CFSVA (Comprehensive Food security and Vulnerability Analysis) – 2007/2008. Overseen by WFP (World Food Program) and CNSA (Coordination Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire)

CNSA/Few Net 2009 Cartographie de Vulnébilité Multirisque Juillet/Aout 2009

CNSA/Fews Net 2005 Profils des Modes de Vie en Haïti

Concern and Fonkoze 2008 Chemin Levi Miyo – Midterm Evaluation Concern Worldwide, by Karishma Huda, and Anton Simanowitz

DINEPA 2012 Challenges and Progress on Water and Sanitation Issues in Haiti National Water and Sanitation Directorate Direction Nationale de l’ Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement – www.dinepa.gouv.ht

Echevin, Damien 2011 Vulnerability before and after the Earthquake. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5850.

http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection.

ECHO 2011 Real-time evaluation of humanitarian action supported by DG ECHO in Haiti 2009 – 2011 November 2010 -April 2011

EMMUS-I. 1994/1995. Enquete Mortalite, Morbidite et Utilisation des Services (EMMUS-I). eds. Michel Cayemittes, Antonio Rival, Bernard Barrere, Gerald Lerebours, Michaele Amedee Gedeon. Haiti, Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-II. 2000. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Florence Placide, Bernard Barrère, Soumaila Mariko, Blaise Sévère. Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-III. 2005/2006. Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD : Macro International.

FAFO 2001 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume II

FAFO 2003 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume I

GoH 2004 Decree de la Constitution regarding Communal Section LIBERTÉ ÉGALITÉ FRATERNITÉ DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE RÉPUBLIQUE D’HAÏTI DECRET Me BONIFACE ALEXANDRE PRÉSIDENT PROVISOIRE

Government of Haiti 2010 Action Plan for National Recovery and Development of Haiti

Gravlee, C. C., Bernard, H. R., Maxwell, C. R., & Jacobsohn, A. 2013 Mode effects in free-list elicitation: Comparing oral, written, and web-based data collection. Social Science Computer Review 30:119–132.

Gravlee, Lance Dept. of Anthropology, University of Florida The Uses and Limitations of Free Listing in Ethnographic Research

Hashemi, Syed M., and Aude de Montesquiou. 2011. “Reaching the Poorest with Safety Nets, Livelihoods, and Microfinance: Lessons from the Graduation Model.” Focus Note 69. Washington, D.C.: CGAP, March.

Himmelstine, Carmen Leon 2012 Community Based Targeting: A Review of CBT programming and literature

Hoskins, A. 2004. Targeting General Food Distributions: Desk Review of Lessons from Experience. Rome, WFP).

IRIN 2010 Haiti: US Remittances Keep the Homeland Afloat. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

http://www.irinnews.org/report/88397/haiti-us-remittances-keep-the-homeland-afloat

Kaufman, Michael. 196. “Community Power, Grasrots Democracy, and the Transformation of Social Life.” In Michael Kaufman and Haroldo Dila Alfonso (eds.), Community Power and Grasrots Democracy: The Transformation of Social Life. London and Otawa: Zed Boks and IDRC.

Kolbe, Athena R., Royce A. Hutson , Harry Shannon , Eileen Trzcinski, Bart Miles, Naomi Levitz d , Marie Puccio , Leah James , Jean Roger Noel and Robert Muggah 2010 Mortality, crime and access to basic needs before and after the Haiti earthquake: a random survey of Port-au-Prince households In Medicine, Conflict and Survival

Krishna, Anirudh 2010 “One Illness Away: Why People Become Poor and How they Escape Poverty” Oxford University Press

Lamaute-Brisson, Nathalie 2009 Pour le ciblage des interventions en matière de sécurité alimentaire. Note d’orientation WFP

Lavallee, Emmanuelle, Anne Olivier, Laure Pasquier-Doumer, and Anne-Sophie Robilliard 2010 Poverty Alleviation Policy Targeting: a review of experiences in developing countries.

Lowenthal, Ira 1984. Labor, sexuality and the conjugal contract. In Haiti: Today and tomorrow, ed. Charles R. Foster and Albert Valman. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Lowenthal, Ira. 1987. Marriage is 20, children are 21: The cultural construction of conjugality in rural Haiti. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University.

Lundahl, Mats. 1983. The Haitian economy: Man, land, and markets. New York: St. Martin’s.

Maguire, Robert E. 1979 Bottom-Up Development in Haiti. Washington, DC: The Inter-American Foundation,

Mansuri, Ghazala and Vijayendra Rao 2013 Localizing Development Does Participation Work? International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

Maxwell, Daniel, Helen Young, Susanne Jaspars, Jacqueline Frize 2009 Targeting in Complex Emergencies Program Guidance Notes. Feinstein International Center, Tufts University

McClure, Marian 1984 Catholic Priests And Peasant Politics In Haiti: The Role Of The Outsider In A Rural Community A paper prepared for presentation at the Caribbean Studies Association meetings St. Kitts May 30 – June 3

Morton, Alice, 1998 The NGO Sector In Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction, World Bank Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

MPCE 2004 Carte de pauvreté d’Haïti, à partir des données de l’ECVH (2001)

Murray, Gerald 1977 The evolution of Haitian peasant land tenure: A case study in agrarian adaptation to population growth. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, Department of Anthropology.

Nicholls, David. 1974. Economic dependence and political autonomy: The Haitian experience. Occasional Paper Series No. 9. Montreal: McGill University, Center for Developing-Area Studies

Pace, Marie with Ketty Luzincourt 2009 Cumulative Case Study: “Haiti’s Fragile Peace”

PAM/CNSA 2007 l’Analyse Compréhensive De La Sécurité Alimentaire Et De La Vulnérabilité

PNUD 2000 Bilan commun de pays du PAM, du FNUAP, de l’UNICEF, de l’OMS/OPS et de la FAO. RPP

Richman, Karen E. 2003. Miami money and the home gal. Anthropology and Humanism 27(2): 119–32.

Romney, A. K., S. C. Weller, and W. H. Batchelder. 1986. Culture as consensus: A theory of culture and informant accuracy. American Anthropologist 88:313–38.

Rotberg, Robert I., and Christopher A. Clague. 1971. Haiti, The politics of squalor. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sali, Jamil 2000 Equity and Quality in Private Education: The Haitian Paradox, Compare, 30(2), 163–178, (p. 165) 3.

Schreiner, Mark 2006 The Progress out of Poverty Index TM: A Simple Poverty Scorecard for Haiti

Schwartz, Timothy. 1998. NHADS survey: Nutritional, health, agricultural, demographic and socio-economic survey: Jean Rabel, Haiti, June 1, 1997–June 11, 1998. Unpublished report, on behalf of PISANO, Agro Action Allemande and Initiative Developpment. Hamburg, Germany.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2000. “Children are the wealth of the poor:” High fertility and the organization of labor in the rural economy of Jean Rabel, Haiti. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2004. “Children are the wealth of the poor”: Pronatalism and the economic utility of children in Jean Rabel, Haiti. Research in Anthropology 22:62–105.

Scott, Lucy and Andrew Shepherd 2013 Microeconomic Indicators of Development Impacts and Available Datasets in Each Potential Case Study Country

Sletten, Pål and Willy Egset. “Poverty in Haiti.” Fafo-paper, 2004.

Smillie, Ian 2001 Patronage or Partnership: Local Capacity Building in Humanitarian Crises Published in the United States of America by Kumarian Press, Inc. 1294 Blue Hills Avenue, Bloomfield, CT 06002 USA.

Smith, Jennie M. 1998. Family planning initiatives and Kalfouno peasants: What’s going wrong? Occasional paper/University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies, no. 13. Lawrence: Institute of Haitian Studies, University of Kansas.

Smith, Jennie M., 2001 When The Hands Are Many Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Smucker, Glenn Richard. 1983. “Peasants And Development Politics: A Study In Haitian Class And Culture”. New School For Social Research. Pages: 511.

Steeve Coupeau 2008: 104 History of Haiti. Greenwood Press: Westport Ct.)

UN 1996 Final report on human rights and extreme poverty, submitted by the Special Rapporteur, Mr. Leandro Despouy’ (28 June 1996) UN Doc E/CN.4/Sub.2/1996/13

UNDP 2011 Cash Programming in Haiti Lessons Learnt in Disbursing Cash Suba Sivakumaran (Subathirai.sivakumaran@undp.org)

USAID (United States Agency for International Development) 1983 Haiti: HACHO Rural Community Development. AID Project Evaluation Report No. 49

USAID 1994 Rapid Assessment Of Food Security And The Impact Of Care Food Programming In Northwest Haiti.

USAID 2013 Performance Indicators Reference Sheets for FFP Indicators http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/PIRS%20for%20FFP%20Indicators.pdf

Verner, Dorte 2008 Making Poor Haitians Count Poverty in Rural and Urban Haiti

Based on the First Household Survey for Haiti. The World Bank Social Development

Sustainable Development Division World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4571

WFP (undated_b) Monitoring & Evaluation Guidelines United Nations World Food Programme Office of Evaluation and Monitoring Via Cesare Giulio Viola, 68/70 – 00148 Rome, Italy Web Site: www.wfp.org

WFP 2006a TARGETING IN EMERGENCIES WFP/EB.1/2006/5‐A

WFP 2006b Thematic Review of Targeting in Relief Operations: Summary Report. Ref. OEDE/2006/1

WFP 2009 Targeting in Complex Emergencies, Programme Guidance. Feinstein International Center, Tufts Universtiy

WFP 2013 Basic Guidance Community-Based Targeting

WFP/EB.A/2004/5‐C).

White, T. Anderson And Glenn R. Smucker 1998 Social Capital and Governance in Haiti. In Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction, World Bank Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

WHO 2013. World Health Statistics

http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2013/en/

Wiens, Thomas and Carlos Sobrado 1998 Rural Poverty in Haiti In Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction, World Bank Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

Wiesmann, Doris, Lucy Bassett, Todd Benson, and John Hoddinott 2009 Validation of the World Food Programme’s Food Consumption Score and Alternative Indicators of Household Food Security. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00870

World Bank 1998 Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction (In Two Volum-les) Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

World Bank 2011 Working Research Paper Echevin2011 Vulnerability before and after the Earthquake. by Damien Echevin World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5850. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection.

World Bank 2013 Design & Implementation: Targeting and Selection. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection

Zaag, Raymond Vander, 1999 Encounters Of Development Knowledges, Identities And Practices In A Ngo Program In Rural Haiti Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Geography and Environment Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Zak, Marilyn and Glen Smucker HAITI DEMOCRATIC NEEDS ASSESSMENT May 1989 USAID (United States Agency for International Development) Office of Caribbean Affairs Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean

NOTES

[i] In 1971-1979 Interim, Papa Doc-appointed ministers, his widow, and daughers had run the government. Baby Doc fell under the spell of a woman name Michelle Bennett, who by many accounts essentially ran the Haitian government (see for example Elizabeth Abbott’s The Duvaliers and Their Legacy.