Going back some 50 years, there have been a series of international interventions meant to blunt the impact of food scarcity and nutritional crisis on impoverished Haitians, particularly mothers and children. The interventions include food aid, feeding strategies, introduction of fortified foods, and promotion of improved cultivars. This article summarizes these interventions, provides a review of the literature for each intervention, and explains how the interventions have complemented one another, most recently becoming a type of integrated nutritional interventionist strategy. It also provides critiques of contradictions and failures in the strategies.

Haiti Anthropology Brief: Institutional Reactions to Food Scarcity and Nutritional Crisis in Haiti

Malnutrition and food insecurity

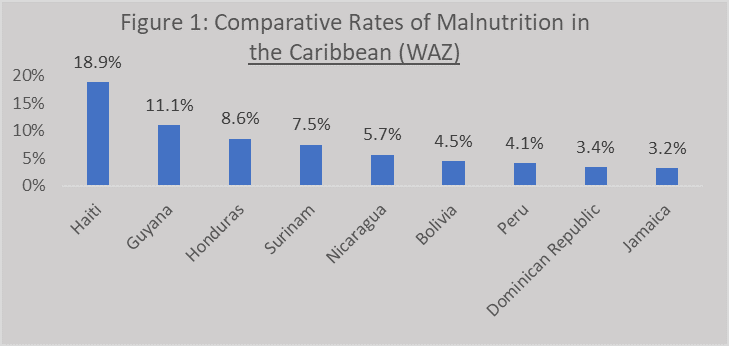

Haiti suffers persistent food insecurity and under-nutrition. Chronic malnutrition has fallen from a 1978 level of 40% of children under 5 years of age to a 2012 level of 22% (EMMUS 2012). Despite this improvement, Haiti lags far behind most other countries in the Caribbean and Latin America (see Figure 1, above). According to WHO (2011), in proportion to those malnourished Haiti has, at 53 per 100,000, the highest death rate from malnutrition in the world.[i] The situation appears worse in rural areas than in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area where 30% of rural children under five are chronically malnourished, and 50% of women are anemic (ENSA, 2011). CNSA (2011) estimates that 38% of households (4 million individuals) are food insecure. Not only is food insecurity high in general, but the poorest sector of the population—comprising 80% of all Haitians—spends 60% to 70% of its income on food (ibid p 84), meaning that there is precious little in the way of income to cushion poor Haitians against a catastrophic economic shock.

Over the past fifty years the international community has addressed Haiti’s problems of malnutrition and intensifying food scarcity in two other ways,

- food assistance to the general population, typically in the form of staples such as rice, wheat and corn, and

- fortified foods intended for pregnant mothers, undernourished women and children.

These interventions have had a profound impact, although—as is often the case with foreign aid—it has often not been the impact that donors and recipients anticipated or hoped for.

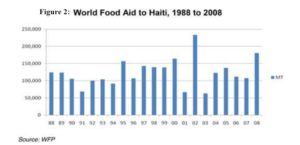

General Food Assistance

The importation of large amounts of general food relief began as long ago as the 1950s but accelerated significantly in association with implementation of World Bank neo-Liberalization development programs of the 1970s and 1980s. By the 1990s “food aid” was arguably the most significant single factor impacting the Haitian popular diet. For example, from 1994 to 1998, the United States, France, and Germany provided a total of 618,000 metric tons of food aid to the country, an annual average of 123,600 metric tons. This was enough to meet the daily nutritional needs (2,200 daily calories) of 10% of the population—then seven million people. [ii]

Whether the free food was having a positive impact on the popular class Haitian nutritional status increasingly became a point of contention. Scholars and former USAID consultants DeWind and Kinley (1988) accused developed countries—most conspicuously the US and France—of “dumping” subsidized agro-industry surplus food on the unprotected agricultural economy of Haiti.[iii] This, they argued, devastated the Haitian agricultural economy and increased migration to cities. There was powerful circumstantial evidence suggesting they were right. Agriculture accounted for 52 percent of Haitian exports in 1980, but only 24 percent in 1987 and 21 percent in 1990. By the mid-1990s, the flow had been reduced to a few mangos and a trickle of coffee. (see post on mango value chain in haiti and report on coffee value chain in Haiti).[iv] Over almost the same period of time, food imports went from 19 percent of total food consumed in the country to more than 50 percent today (ACF 2017).

Along with the agricultural decline came ballooning rates of urbanization. When the process began in the 1950s, about 80% of the Haitian population was rural and dependent on agriculture. Today 50% of the population is rural and dependent on agriculture. Along with this shift came increasing urban squalor, unrest, and political instability. By the first decade of the 2000s a chorus of mainstream humanitarian organizations, including Oxfam International, Christian Aid, and CARE International, had joined the critics in condemning subsidized food imports and wantonly distributed food aid as a massive disincentive to production that was making Haiti’s problems more grave.

In 2008, world food prices spiked and food riots broke out in Haiti and other poor countries. USAID and WFP then joined their own critics and changed their food-security mission objectives to emphasize food “sovereignty,” i.e. the capacity of the population to feed itself.[v]

Still, massive food relief continued to flow into Haiti. Following the 2010 earthquake the international community sent 310,000 metric tons of emergency food aid. That was for a single year, 2010. It was enough to provide for all of the calorific needs of 1.3 million adults. Half of that food was US surplus, and it came over the objections of then Haitian President Rene Preval, who three months after the earthquake had asked US President Barack Obama to stop sending food. Preval said that, “If they continue to send us aid from abroad–water and food–it will be in competition with the national Haitian production and Haitian commerce.” Nevertheless, in 2011 more food came, much of it distributed in massive school feeding programs. As with many previous food aid programs, much of this food was embezzled and sold on the open market, putting it in direct competition with locally grown commodities (see Food Aid Part 1 and Food Aid Part 2).

From 2011 to the present, WFP has pursued a policy of stocking food in warehouses throughout the country. The stated goal was to prepare for rapid response to the next crisis, but even when the food was not needed—arguably, it never has been needed—it has been frequently pilfered. In the most dramatic cases, trucks attempting to remove unneeded provisions have been raided by local populations, the “aid” pillaged and, as with the embezzled food, sold on the local market. This is not to say there were no efforts to encourage local production after the 2008 food crisis. WFP, for example, has increasingly used cash rather than food as a mechanism to provide relief to the poor, allowing recipients to use aid money to buy from local farmers. But, de facto, efforts to encourage local food production through local purchases have been weak.

Fortified Foods

Fortified humanitarian-sourced foods are, in theory, distinct from general food relief. During the 1960s USAID-funded Mothercraft Centers were widespread in Haiti (Also called CERN, based on the French, Centre d’Education et Rehabilitation Nutritionelle). The centers treated malnourished children with inexpensive local foods (Berggren 1971, Berggren et al. 1984; King et al. 1968; 1974; 1978). Nutritionists who designed and studied the Mothercraft centers lamented the heavy dependence on animal source foods, and it was in this context that fortified processed foods entered the popular diet. These included akamil and akasan (both pureed and boiled bean-cereal mixtures), and chanm chanm (peanut coconut powder). The emphasis was on local foods, primarily. Illustrative of the trend, Haiti’s Bureau of Nutrition (BND) and Virginia Polytechnic Institute developed akamil (AK-1000), a weaning and malnutrition treatment formula, to meet the following criteria: [vi]

- appropriate for pre-school children

- contain 10% to 20% of high quality protein

- made exclusively of local products

- simple enough to be made at home or in the village

- inexpensive enough for poor people to afford it

By the 1980s and 1990s imported fortified cereal products entirely supplanted the trend of searching for local supplements to be used in weaning and nutritional programs. Indeed, Haiti was awash in the food aid mentioned above, the vast bulk of which was and is Soy Fortified Bulgur (Corn Soy Blend was the second most common cereal product).[vii] By the early 2000s the concerns of nutritionists had been reversed, and they were lamenting the low reliance on Animal Source Foods. Ruel et. al. (2003) found that without the availability of animal products, such as meat, milk, cheese, and eggs, Haitian mothers using mixtures of local produce and specially fortified imported products such as US government wheat-soy blend (WSB) and corn-soy blend (CSB) were unable to supply infants and young children with sufficient micronutrients—particularly iron and zinc. It was in this context that Therapeutic Foods emerged. [viii] [ix]

Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food

During the 1990s, Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Foods (RUTFs) began appearing as a new armament in the international humanitarian aid war against malnutrition in developing countries. RUTFs are a scientifically formulated response to the challenges of addressing malnutrition, weaning, and school feeding in a nutritionally insecure environment. RUTFs typically include zinc, iron, iodine and vitamins A and B12, while also providing protein and essential fatty acids. In short, they have it all.

Early RUTFs included F-100, a solid therapeutic milk developed for ACF (Accion Contre le Faim), vitamin and micronutrient rich supplement called Sprinkles developed for UNICEF; High Energy Biscuits and Compressed Food Bars developed for WFP; and peanut butter formulas from the social enterprise Nutriset. Peanut-based formulas are especially effective.

Peanut Based RUTFs

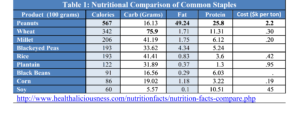

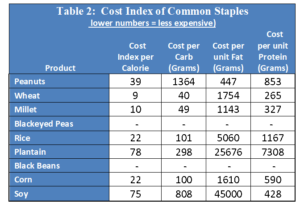

Peanuts alone are a type of super food. They blow the top off the nutritional chart regarding protein and fat content (Table 1). Nutriset, with its Plumpy Nut brands, initiated a patented process of using milk and soy enriched peanut blends. However, while high in calories, fat and proteins, in terms of cost, peanuts compare favorably to other staples only with regard to fat; see Table 2.

Biofortification

A recent response to the critiques of imported foods has been biofortification–the deliberate genetic selection for more highly nutritious varieties of locally grown staple crops. The attention given biofortification is indicative of the interest in joining the goal of local production (food sovereignty) with programs that address malnutrition. In Haiti, the World Bank supports ORE (Organization for the Rehabilitation of the Environment), a small grassroots organization that started a crop-breeding program in 2004 aiming to enhance the nutritional content of Haitian staple crops.

The impulses to develop more nutritious foods and to encourage local production have merged into an effort to produce RUTFs in Haiti using local products, with peanuts being, as seen above, among the most promising candidates for the principal ingredient.[x] Local production, manufacturing, fortification, and packaging of fortified peanut paste products, collectively, form a type of perfect response to the critiques of food aid seen earlier, and to the value of promoting food sovereignty versus simply food relief. Buying locally will stimulate production. Fortifying and producing locally will provide an accessible, nutritious product. Humanitarian enterprises have determined that the strategy was overwhelmingly logical, and set out to implement it.

RUTF Factories in Haiti

In 2003 Patricia Wolff started such a program, Meds and Food for Kids (MFK), aimed at producing a peanut-based RUTF sourced and produced in Haiti. In 2010 she was able to raise $3.2 million, including a $700,000 loan, with which she built a state-of-the-art RUTF factory in Cap-Haitien. The factory produced a mix of peanuts, soy and vitamin supplements. The intention was to supply the major humanitarian organizations working in Haiti. It was off to a promising start. The very next year Partners in Health (PIH) received a $6 million grant from Abbot Laboratories to build an even bigger factory.

Together MFK and PIH may have made a greater total investment in ready-to-eat packaged food production than all other Haitian manufacturers combined, meaning even those in the private sector. Formerly deluged with food aid, none of which was produced in country, Haiti suddenly seemed poised to begin producing more RUTFs than it could use. Then, the situation grew more complicated when both factories entered production dependent on selling to the same clients, UNICEF and WFP. [xi] [xii]

The clash highlighted two common pitfalls of the aid industry: poor coordination among NGOs and the donor driven tendency toward competitiveness in the pursuit of fundable opportunities. USAID provided much of the funding to organize farmers and improve production to supply MFK with wholesome peanuts. It also provided the money for the equipment to transform the peanuts into a fortified peanut butter blend that could be used in nutritional clinics. But in 2013, much of the unused emergency food aid discussed earlier—stored throughout Haiti in the ill-conceived preparation for another disaster on par with the 2010 earthquake—was transferred to WFP, the agency overseeing internationally funded food security in Haiti. This gave WFP so much fortified bulgur that it no longer needed MFK peanut butter blends for its nutritional programs. WFP promptly canceled its contracts, leaving MFK struggling to financially survive as a social enterprise. To cut costs, MFK increased importation of less expensive peanuts from abroad. The organization also began to explore opportunities to sell its peanut products on the local market to help cover costs. This threatened to transform MFK into a Trojan Horse: having entered Haiti to promote local production, it was then being considered as a vehicle to facilitate the sale of imported peanuts in direct competition with local farmers, repeating the pattern seen with general food assistance. A logical solution to the dilemma—one that MFK staff is pursuing–would be to make RUTFs profitable on the local market, thereby cutting the need for international aid organizations as clients and closing the local production-nutrition loop.

WORKS CITED

Alvarez and Murray, 1981Alvarez, M.D.Murray, G.F. Socialization for scarcity: Child feeding beliefs and practices in a Haitian village. United States Agency for International Development

Bailey, M., 2006 “Analysis of Market in Haiti for PL480 Title II Packaged Vegetable Oil” USAID Purchase No. 521-O-00-06-00079, August 2006

Bastien, Remy. 1961. Haitian rural family organization. Social and Economic Studies 10(4):478–510.

Beghin, I, Fougere, W., King, K.W. (1970), L’Alimentation et la Nutrition en Haiti”, publication de L’I.E.D.E.S., Presses Universitaires de France, 108, Blvd. Saint-Germain, Paris.

Berggren et al. 1984; King et al. 1968; 1978; Berggren 1971, Beaudry-Darismé 1971; Beaudry-Darismé and Latham 1973; Berggren et al. 1985; Mduduzi N.N. 2013; Dornemann and Kelly 2013; Schwartz 2009

Berggren, Gretchen, Nirmala Murthy, and Stephen J Williams. 1974. Rural Haitian women: An analysis of fertility rates. Social Biology 21:368–78.

CARE 2012 Gender Survey CARE HAITI HEALTH SECTOR Life Saving Interventions for Women and Girl in Haiti Conducted in Communes of Leogane and Carrefour, Haiti

CFSVA (Comprehensive Food security and Vulnerability Analysis) – 2007/2008. Overseen by WFP (World Food Program) and CNSA (Coordination Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire)

CIAT 2015 AgroSalud Project (www.AgroSalud.org)

CNSA (Coordination Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire), 2014 Beneficiary Targeting in Haiti :Detection Strategies, by Timothy Schwartz

CNSA (Coordination Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire), 2014 Beneficiary Targeting in Haiti :Detection Strategies, by Timothy Schwartz

CNSA and WFP’s 2007 Analyse Compréhensive de la Sécurité Alimentaire et de la Vulnérabilité (CFSVA) Written by Timothy Schwartz

CNSA’s 2011 Enquête Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire (ENSA),

Demographic Health Surveys (DHS or EMMUS) from the year 1995 (N=4,944 households), year 2000 (N=9,595 households), year 2005 (N=9,998 households), and year 2012 (N=13,181 households)

DeWind, Josh and David H. Kinley, 1988 Aiding Migration: The Impact Of International Development Assistance On Haiti 3rd

EarthTech 2014 Lafiteau Social Impact Assessment on behlf of GB Group

Echevin, Damien 2011 Vulnerability before and after the Earthquake. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5850.

http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection.

EMMUS 2012 Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haïti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti

EMMUS-I. 1994/1995. Enquete Mortalite, Morbidite et Utilisation des Services (EMMUS-I). eds. Michel Cayemittes, Antonio Rival, Bernard Barrere, Gerald Lerebours, Michaele Amedee Gedeon. Haiti, Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-II. 2000. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Florence Placide, Bernard Barrère, Soumaila Mariko, Blaise Sévère. Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-III. 2005/2006. Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD : Macro International.

FAFO 2001 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume II

FAFO 2003 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume I

FAO Stat 2000

Farmer, Paul, 1988Bad Blood,Spoiled Milk: Bodily Fluids as Moral Barometers in Rural Haiti (1988)

Gardella, Alexis 2006 Gender Assessment for USAID Assessment Country Strategy

HarvestPlus 2013 Prioritizing Countries for Biofortification Interventions Using Country-Level Data HarvestPlus Working Paper | authors, Dorene Asare-Marfo Ekin Birol Carolina Gonzalez Mourad Moursi Salomon Perez Jana Schwarz and Manfred Zeller

Hinds, . M.J. M. Jolly, R.C. Nelson”, Y. Donis”, and E. Prophete”

IDB 1999 see Gardella, Alexis,

International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2015 HAITI SELECTED ISSUES Prepared By Lawrence Norton, Joseph Ntamatungiro, Daniela Cortez, Gabriel Di Bella (all WHD), Emine Hanedar (FAD), and Anta Ndoye (SPR) Approved By The Western Hemisphere Department

Institute Haitien de L’enfance et al (2000),

Inter-American Development Bank (1999). Facing up to Inequality. Washington D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank.

IRIN 2010 Haiti: US Remittances Keep the Homeland Afloat. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs http://www.irinnews.org/report/88397/haiti-us-remittances-keep-the-homeland-afloat

Jensen, Helen 1990 Food consumption patterns in Haiti Center for Agriculture and Rural Development. Iowa State University Staff Report 90-SR 50

Jolly and Prophete, 1999

Katherine Harmon Courage | July 2, 2011 | http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2011/07/02/whats-in-your-wiener-hot-dog-ingredients-explained/

King, K.W. Fougere, W., and Beghin, I. (1966) Un Melange de proteins vegetales (Ak-1000) pour les enfants haitiens.Ann Soc. Belge Med. Trop. Vol 46, 6, pp 751-754.

King, K.W., Fougere, William, Foucald, J., Dominique, G., and Beghin, I (1966) Responswe of [preschool children to high intakes of Haitian cereal-bean mixtures. Arcivos Latinoamericanos de Nutricion 16:1. pp 53-64.

Leyburn, James G. 1966 (originally 1941) The Haitian People. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lowenthal, Ira 1984. Labor, sexuality and the conjugal contract. In Haiti: Today and tomorrow, ed. Charles R. Foster and Albert Valman. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Lowenthal, Ira. 1987. Marriage is 20, children are 21: The cultural construction of conjugality in rural Haiti. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University.

Lundahl, Mats 1983 The Haitian Economy: Man, Land, and Markets. New York: St. Martins Press.

Metraux, Rhoda 1951 Kith and kin : a study of Creole social structure in Marbial, Haiti. PhD Dissertation: Columbia University.

Mintz, Sidney 1974. Caribbean transformations. Chicago: Aldine.

Moreau, St Mery 1797 Description de la Partie Francaise de Saint-Domingue Paris: Societe de l’Histoire de Colonies Francaises, 1958 v. 2

Murray Gerald F. 1972. The economic context of fertility patterns in a rural Haitian community. Report submitted to the International Institute for the Study of Human Reproduction. New York: Columbia University.

Murray, Gerald F. 1977 The Evolution of Haitian Peasant Land Tenure: Agrarian Adaptation to Population Growth. PhD Dissertation: Columbia University

Murray, Gerald 1977 The evolution of Haitian peasant land tenure: A case study in agrarian adaptation to population growth. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, Department of Anthropology.

Nicholls, David. 1974. Economic dependence and political autonomy: The Haitian experience. Occasional Paper Series No. 9. Montreal: McGill University, Center for Developing-Area Studies

ORE Organization For The Rehabilitation Of The Environment Biofortified staple food to help reduce malnutrition

PAM/CNSA 2007 l’Analyse Compréhensive De La Sécurité Alimentaire Et De La Vulnérabilité

Richman, Karen E. 2003. Miami money and the home gal. Anthropology and Humanism 27(2): 119–32.

Roman S.B. (2007). Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices in Rural Haitian Women. UCHC Graduate School Masters Theses 2003–2010. Paper 141.

Schwartz, Timothy. 1992. Haitian migration: System labotomization. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville.

———. 1998. NHADS survey: Nutritional, health, agricultural, demographic and socio-economic survey: Jean Rabel, Haiti, June 1, 1997–June 11, 1998. Unpublished report, on behalf of PISANO, Agro Action Allemande and Initiative Developpment. Hamburg, Germany.

———. 2000. “Children are the wealth of the poor:” High fertility and the organization of labor in the rural economy of Jean Rabel, Haiti. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

———. 2004. “Children are the wealth of the poor”: Pronatalism and the economic utility of children in Jean Rabel, Haiti. Research in Anthropology 22:62–105.

______. 2009 Fewer Men, More Babies: Sex, family and fertility in Haiti. Lexington Press. USA

______.2011 Fair Wage in Haiti: Assessment Report. International Trade Center’s Ethical Fashion Initiative. Unpublished Report

Simpson, George Eaton

1942 Sexual and Family Institutions in Northern, Haiti. American Anthropologist 44:655-674.

Sletten, Pål and Willy Egset. “Poverty in Haiti.” Fafo-paper, 2004.

Smith, Jennie M. 1998. Family planning initiatives and Kalfouno peasants: What’s going wrong? Occasional paper/University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies, no. 13. Lawrence: Institute of Haitian Studies, University of Kansas.

Smucker, Glenn Richard 1983 Peasants and Development Politics: A Study in Class and Culture Ph.D. dissertation, New School for Social Research.

Society for Nutrition Education July 25th, 2010 Danielle Dalheim, RD http://www.sneb.org/conference/documents/Frito-Lay_Coffee_And.pdf

Stam, Talitha 2012, From Gardens to Markets Rural women on the move to urban markets, Route Seguin Haiti A Madam Sara Perspective Commissioned by CORDAID for the IS ACADEMY Human Security in Fragile States

Technoserve 2012 HAITIAN PEANUT SECTOR ASSESSMENT Strategic Industry and Value Chain Analysis (Haiti)

Kurlansky, Mark 1999 The Fish That Changed the World

The Guardian 2015. The west’s peanut butter bias chokes Haiti’s attempts to feed itself Guardian Global development http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jul/10/haiti-peanut-butter-food-aid-malnutrition Accessed, 1/03/15

USDA 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Chapter 6. (Accessed 18/12/09) (http://www.health.gov/DIETARYGUIDELINES/dga2005/document/html/chapter6.htm)

Verner 2008: 201, using HLCS 2001

WHO (2009) World Health Organization, Global and regional food consumption patterns and trends http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/3_foodconsumption/en/index3.html

NOTES

[i] http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/cause-of-death/malnutrition/by-country/

[ii] Specifically, it was enough to meet the nutritional needs of the entire population of Haiti for twenty-seven days per year. See Schwartz, Timothy 2012. Travesty in Haiti, Chapter Seven.

[iii] DeWind, Josh and David H. Kinley, 1988 Aiding Migration: The Impact Of International Development Assistance On Haiti 3rd

[iv] Between the early 1980s and 2000 the Haitian government, largely guided by USAID, invested only 5% of it’s budget in the agricultural sector while investing heavily in industry. At the same time food aid flooded into the country.

[v] In 2008 petroleum prices increased and with it so did global food prices, precipitating riots in developing countries around the world, not least of all Haiti. With that unrest came a wide spread agreement that food aid may indeed be anathema to development. A concomitant and abrupt about face in development policies ensued. The same year the USG launched its new program, Feed the Future, Global Hunger and Food Security Initiative. The goal was to make countries “food sovereign”, meaning self-sufficient. It was a radical change from 10 years earlier when USAID website assured visitors that food-aid helped move developing countries away from being food producing countries and into being food consuming countries that bought US produce.

WFP also changed strategies. Since its inception in 1961 the primary goal of the United Nations World Food Program (WFP) has been to provide food assistance to those most vulnerable to hunger, usually women, children, the sick and the elderly. Similar to the USG, with the 2008 Global Food Crisis WPF made what it called a “historical shift” from a food aid agency to a food assistance agency. WFP now strives to eradicate hunger and malnutrition, but with the ultimate goal in mind of eliminating the need for food aid itself. WFP’s strategic plan for 2008-2013 lays out five objectives for the organization:

- Save lives and protect livelihoods in emergencies

- Prevent acute hunger and invest in disaster preparedness and mitigation measures

- Restore and rebuild lives and livelihoods in post-conflict, post-disaster or transition situations

- Reduce chronic hunger and under-nutrition

- Strengthen the capacities of countries to reduce hunger, including through hand-over strategies and local purchase

In September 2008 WFP launched a program that helps small farmers access agricultural markets and to become competitive players in the market place. It reinforced programs that improved agricultural production, post-harvest handling, quality assurance, group marketing, and agricultural finance. WFP then signed contracts for more than 207,000 metric tons of food valued at US$75.6 million, all from producers in 20 developing countries. Haiti was not one of them.

In Haiti WFP provides an excellent example of the difficulty in changing practices and honing them to promote production. While there has been much talk of purchasing locally, in the year following the earthquake WFP imported over 300,000 tons of surplus food from developed countries. The cost of the operation in food and money spent on transport and administration was US$475 million. They bought no Haitian rice. But it would have been a good deal: it sold for US$13.27 per sack in 2010, two thirds what it sold for before the earthquake.

None of this is to say that WFP does not want to buy local. In November 2011, high level WFP directors in Washington and the WFP/Haiti country declared an interest in purchasing locally. The problem, they pointed out, is organizing dependable supply systems.

CARE International published a 2006 white paper distancing itself from food monetization as not compatible with the interests of the people it sought to help. As a consequence CARE no longer had the funds for its other programs, and thus withdrew from most of its NW Haiti activity zone. CARE reconfigured its aid strategy, partnering with the Haitian government organization PRODEP and focusing on Community Driven Development, disaster relief, and assistance to HIV infected individuals and their families. CARE continues however to participate in widespread food distribution.

[vi] Beghin, Fougere and King, 1970 History of AKA1000 in Haiti Drs. Warren and Gretchen Berggren 2005 gberggren@aol.com

Institute Haitien de L’enfance et al (2000),

King, K.W., Fougere, William, Foucald, J., Dominique, G., and Beghin, I (1966) Responswe of [preschool children to high intakes of Haitian cereal-bean mixtures. Arcivos Latinoamericanos de Nutricion 16:1. pp 53-64.

King, K.W. Fougere, W., and Beghin, I. (1966) Un Melange de proteins vegetales (Ak-1000) pour les enfants haitiens.Ann Soc. Belge Med. Trop. Vol 46, 6, pp 751-754.

Beghin, I, Fougere, W., King, K.W. (1970), L’Alimentation et la Nutrition en Haiti”, publication de L’I.E.D.E.S., Presses Universitaires de France, 108, Blvd. Saint-Germain, Paris.

[vii] Fintrac 2010, p 16. 52

[viii] See Berggren et al. 1984; King et al. 1968; 1978; Berggren 1971, Beaudry-Darismé 1971; Beaudry-Darismé and Latham 1973; Berggren et al. 1985; Mduduzi N.N. 2013; Dornemann and Kelly 2013; Schwartz 2009

Marie T. Ruel, Cornelia Loechl, Purnima Menon, and Gretel Pelto (2003) “Can Fortified Donated Food Commodities Significantly Improve the Quality of Complementary Foods?” International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, D.C. Contact author at m.ruel@cgiar.org.

[ix] In practice fortified foods have also come for general relief. And because of the sheer bulk of the food provided, both general feeding and poorly controlled targeting of mothers and children have been widely criticized as negatively impacting local agricultural production. Even in the case of imported fortified foods, critics and production minded observers lament imported foods as lost opportunity to encourage local production and what has come to be known as food sovereignty. The importance of this trend cannot be gainsaid because if it is true then what is occurring is that short-term nutritional programs have been undermining long-term efforts to address malnutrition and under-nutrition, and the economic development that can help Haitians overcome these problems. Because of the importance of these issues, the points are elaborated below.

[x] HarvestPlus 2013 Prioritizing Countries for Biofortification Interventions Using Country-Level Data HarvestPlus Working Paper | authors, Dorene Asare-Marfo Ekin Birol Carolina Gonzalez Mourad Moursi Salomon Perez Jana Schwarz and Manfred Zeller

CIAT 2015 AgroSalud Project (www.AgroSalud.org)

[xi] The Guardian 2015. The west’s peanut butter bias chokes Haiti’s attempts to feed itself Guardian Global development http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jul/10/haiti-peanut-butter-food-aid-malnutrition Accessed, 1/03/15

[xii] ORE Organization For The Rehabilitation Of The Environment Biofortified staple food to help reduce malnutrition