The most significant measures for both the market woman and the typical customer in Haiti are those used to measure the most popular staple foods: cans and cups from the mammit (3 litre can), to the ti mammit (500 ml can), to the gode (440 ml), demi gode (320 ml) and the bwat let (180 ml) are used to measure grains and pulses such as corn, rice, beans as well as sugar, salt and even charcoal. Also common are bottles used to measure cooking oil, gas for lamps, and raw rum. At a higher level, and most familiar only to the big traders and transporters, are the sacks, buckets and drums used for wholesale and convenient for bulk transport.

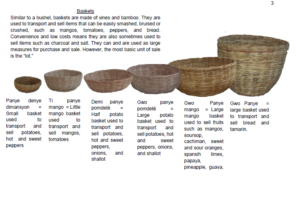

Somewhat different are the baskets used to measure and transport products that could otherwise be crushed, such as mangoes, tomatoes, oranges, and vegetables as well as bread. Although woven baskets are an ancient means of handling foods, nothing has yet completely replaced them–although imported plastic kivet (basin) also also common, they are not dealt with in this post and typically not used as a unit of measure. Below we offer a visual and nearly, but not totally complete summary of measures used in the informal Haitian economy.[i]

These measures are a main feature of the domestic economy, such that every child becomes familiar with them when running errands to the market. For the machann (vendor) they represent the most common measures used to buy and sell.

Discussion: Importance of Using Volume vs. Weight Measures

Measuring by volume is not peculiar as it might seem. It was not a long time ago that farmers in North America and Europe also preferred to use volume vs. weight measures. Pecks and bushels were prevailing bulk measures for fruit and grains. People bought by the pint, quart or gallon. They were simply more practical than having to lug a scale around. NGOs and businesses dealing with the informal economy in Haiti sometimes insist on weights as a unit of measure. A case in point is WFP local procurement school feeding programs. Doing so causes confusion among the purchasers and cooks in the school feeding program, most of whom are significantly less educated than their Western aid-worker counterparts who manage the programs–meaning the burden of calculating in an unfamiliar measurement system should arguably fall to the aid-worker and not the ‘beneficiaries.’ It also causes conflict in markets. Merchants not only calculate in volume measures, they derive profits through relationships between the different measures. The cultural rule is that profits are earned not by price but by volume. Thus, a mamit sells for specific price and 5 ti mamit (little mamit) always sell for exactly the same price as one Big Mamit, but there are really 6 ti mamit in a one mamit. In this way, for every mamit that a vendor sells in the form of ti mamit (meaning, for every 5 mamit) she earns a profit of 1 ti mamit. Thus, because of the prevalence of these measures, because the local system uses them as part of a system for making profit, and the difficulty for local stakeholders in adapting to weights, it would behoove aid workers–if they actually intend to help local people and make their projects effective and accepted by local merchants– to consider using local volume measures rather than weights.

[1] NGOs and businesses dealing with the informal economy sometimes insist on weights as a unit of measure. A case in point is WFP local procurement school feeding programs. Doing so causes confusion among the purchasers and cooks in the school feeding program, most of whom are significantly less educated than their BND and WFP counterparts who manage the program. It also causes conflict in markets. Merchants not only calculate in volume measures, they derive profits through relationships between the different measures. The cultural rule is that profits are earned not by price but by volume. Thus, a mamit sells for specific price and 5 Little Mamit always sell for exactly the same price as one Big Mamit, but there are really 6 Little Mamit in a Big Mamit. In this way, for every Big Mamit that a vendor sells in the form of little Mamit, she earns a profit of 1 Little Mamit. Because of the prevalence of these measures and the difficulty for local stakeholders in adapting to weights, it would behoove WFP and BND to consider using local measures rather than weights.

[2] A useful conversions to know:

1 gwo mamit of rice/corn/millet/cacao = ~2.7 kg

1 gwo mamit of roasted cashew nuts or shelled peanuts = ~ 1.7 kg

1 gwo mamit of raw cashew nuts or shelled peanuts = ~2.4 kg