In the 1960s and 1970s the typical gran neg or gran dam (Patron) in provincial Haiti was an individual belonging to a large family that, a) had more and better land than most people in the region, b) a better education, c) urban connections, but, d) was heavily invested in land, agricultural production, livestock rearing and, very importantly, the aggregation and processing of local produce destined for export, typically coffee, cacao, rum, sisal, aloe, goat skins, and castor oil. And perhaps more importantly than anything else, e) heavily invested in social capital. All had extensive networks of kliyan, people who were dependent on them for credit, as purchasers of their produce, and for sharecropping arrangements that brokered access to land and animals. All had many godchildren, and while some were pious Catholics, it was not uncommon for the wealthier men among them to have 20 or more recognized offspring. These economic patwon/kliyan relations, and fictive kinship relations, were expanded exponentially through the similar relations of their own siblings. It would have been rare during the 1960s to find an individual in rural Haiti who could not trace some kinship relationship to a local leader. Today these leaders are typically remembered as honest notables who would judge local disputes, whose decisions were respected, who were above reproach and who not only dominated the Community Councils, but whose presence and consent was indispensable in the acceptance of any community decision.

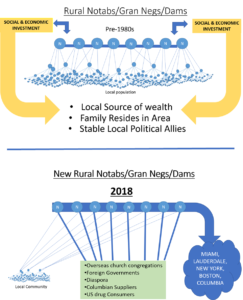

The extent of the romanticism of the notab of yesteryear is in stark contrast with those of today. Today the wealthiest people in any given rural area are typically described as volé (thief), showy (gen byen/pran poz), not invested in the local economy and not interested in community well-being or development. Although some of this discrepancy in notab of the past vs those of the present may indeed be written off to romanticism, the consistency of the accounts from elders in rural area cannot be dismissed. Moreover, the shift from an elite invested in the local economy to one depending on siphoning off aid and money meant for community services and investment in infrastructure is consistent with the shift in community opinion. The criticisms also coincide with changing national political and demographic trends. Indeed, if we look at these changes in the political, economic and demographic factors we should expect a disconnection between the wealthiest members of the community and the vulnerable masses: if for no other reason than, beginning in the 1970s, almost all of the members of the traditional rural elite have left.

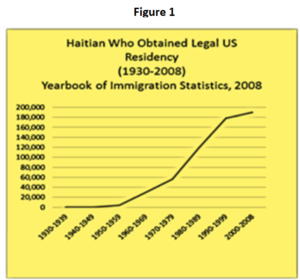

With the political turmoil of this era and the collapse of the formal economy and exports (see this post), economic and social rural leaders increasingly invested, not in the local economy, but in getting themselves and their children out of the region. The extent of the exodus and the shift in the economic leadership base from local economy to charity cannot be gainsaid. Far-West Haiti during the 1990s, is an example. The eight most important community leaders living in the region where I conducted my doctoral research in 1990 had 44 children over the age of 18 years: not a single one had remained in the area. 19 were living in Port-au-Prince; 25 were in the US and Canada (see Schwartz 1991).

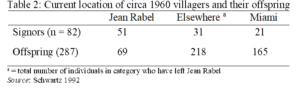

Similar evidence comes from the movement of people out of the village of Jean Rabel. I took a list of Jean Rabel village residents from a 1960 open letter to then President Francois Duvalier that I found in a Port-au-Prince newspaper (Nouvelliste 1960). The letter was a plea for aid after a storm had washed out the local cemetery, uncovering graves and sending coffins and cadavers floating through the streets. There were 178 signatures on the letter. Using local informants, we were able to identify eighty-two of the individuals listed in the letter, all the rest presumably having long ago left with their entire families. For sixty-nine of the individuals, information was obtained on the number of children they had and the current whereabouts of these children. Of the individuals, thirty-one had left Jean Rabel; twenty-one of these had immigrated to Miami. Of the 287 offspring identified, 76 percent had left Jean Rabel and 57 percent had immigrated to the United States.[i]

And I found the same patterns in more rural areas. In a 1992 random sample of two rural areas near Jean Rabel (specifically, La Voltiere in the commune of Mole St. Nicolas), I compared tin-roofed households (a sign of higher income) to thatch-roofed houses (a sign of lower income).[ii] None of the sixty-nine heads of thatch-roofed households had any children in the United States and only three had a sibling in the United States. In contrast, seven of twenty-seven tin-roofed household heads had siblings and four had children living in the United States (Schwartz 1992).

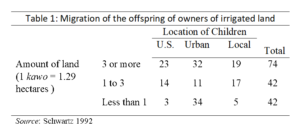

It is not that migrant families have more money because they have migrants. It is the inverse. As one moves from the poorest rural areas into those zones where there is a relative concentration of wealth, migration becomes the dominant theme. In one of the only irrigated zones in the region I found that 74 percent of all children of the largest landowners had left the region. Thirty-one percent (31%) were reported as being in the United States, and this percentage did not take into consideration the age of the children and the fact that some were still very young and hence had not yet emigrated (see Tables 1 and 2).

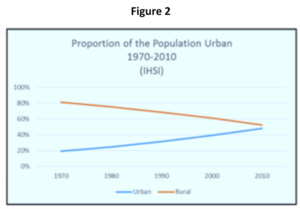

The shift also had an economic dimension. Investment in out-migration created an economic vacuum. As elsewhere in Haiti, enterprises that thrived in the Far-West up through the 1980s collapsed in the 1990s. By 1996 rum, sisal, coffee, goat skins, aloe, and castor oil were no longer aggregated in significant quantities to justify exportation. Into the void came missionaries, orphanages, schools, churches and NGOs, all of which had–and still have–their economic base in donations from overseas. During the 1990s–and largely true today–all clinics, hospitals, road construction, irrigation, soil conservation, and schools—even the public Liceys (high schools)—were heavily dependent on missionaries, UN agencies, and overseas based NGOs. This is true whether or not they were in name owned, constructed or maintained by the Haitian State. Consequently, for the majority of the rural population far and away the single most lucrative entrepreneurial opportunity became gaining access to those entities responsible for vectoring overseas aid. Whether for selfish or altruistic motivations, be it preacher, priest, orphanage owner, clinic owner, association director or those few non-charity endeavors such as merchant, ship owner, land owner, or politician, the major stakeholders earning money in rural Haiti and who were determined to keep a stake there moved his or her family to Port-au-Prince, Florida, New York, Boston, Montreal or Toronto while keeping an economic base in rural Haitian industry of charity. What they did with the money they earned or embezzled is just as important. Although they may have derived profits from their participation in regional overseas-funded charity and development enterprise, they overwhelmingly made their own personal investments in the safer, more stable, insurable and profitable external economies. They opened bank accounts in the US and Canada, bought homes and businesses there, and sent their children to school there. Moreover, while most observers prefer to ignore the topic, the situation was aggravated by the concurrent and very real emergence of illicit drug trafficking as the industry of choice for what has become provincial and arguably even metropolitan Haiti’s most powerful elite, even more powerful than the new custodians of charity. What all this has meant for the social system, the local bureaucracy and social capital is that a sense of community responsibility and community censure has been sapped, leaving little reason to expect anything different than the fraud, corruption, and nepotism for those with access to aid or the state bureaucracy. But perhaps more importantly than anything else, among the poor who are left behind, what remained of particular survival strategies they depended on for the past 200 years allegiance to household and family and values, loyalties that are anathema to the impartial participation in targeting and aid distribution that the State, NGOs and International organizations purport as idealize.

NOTES

[i]. The identification of “prestigious” is simply those individuals who were most easily recognized, about which informants had no questions, and were double-checked without complication.

[ii]. These samples were chosen from lists made in two neighborhoods. Beginning at a random starting point, every fifth household was chosen from the lists.

Bibliography

Aba Grangou 2012 Unpublished

ALNAP. 2012 Responding To Urban Disasters: Learning From Previous Relief And Recovery Operations November www.alnap.org/resources/lessons.

Bastien, Remy. 1961. Haitian rural family organization. Social and Economic Studies 10(4):478–510.

Berggren, Gretchen, Nirmala Murthy, and Stephen J Williams. 1974. Rural Haitian women: An analysis of fertility rates. Social Biology 21:368–78.

Borgatti, S.P. 1992. ANTHROPAC 4.0 Methods Guide. Columbia: Analytic Technologies.

CARE 2013a The Kore Lavi Program (United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance Office of Food for Peace

CARE 2013b Gender Survey CARE HAITI HEALTH SECTOR Life Saving Interventions for Women and Girl in Haiti Conducted in Communes of Leogane and Carrefour, Haiti

CFSVA (Comprehensive Food security and Vulnerability Analysis) – 2007/2008. Overseen by WFP (World Food Program) and CNSA (Coordination Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire)

CNSA/Few Net 2009 Cartographie de Vulnébilité Multirisque Juillet/Aout 2009

CNSA/Fews Net 2005 Profils des Modes de Vie en Haïti

Concern and Fonkoze 2008 Chemin Levi Miyo – Midterm Evaluation Concern Worldwide, by Karishma Huda, and Anton Simanowitz

DINEPA 2012 Challenges and Progress on Water and Sanitation Issues in Haiti National Water and Sanitation Directorate Direction Nationale de l’ Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement – www.dinepa.gouv.ht

Echevin, Damien 2011 Vulnerability before and after the Earthquake. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5850.

http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection.

ECHO 2011 Real-time evaluation of humanitarian action supported by DG ECHO in Haiti 2009 – 2011 November 2010 -April 2011

EMMUS-I. 1994/1995. Enquete Mortalite, Morbidite et Utilisation des Services (EMMUS-I). eds. Michel Cayemittes, Antonio Rival, Bernard Barrere, Gerald Lerebours, Michaele Amedee Gedeon. Haiti, Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-II. 2000. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Florence Placide, Bernard Barrère, Soumaila Mariko, Blaise Sévère. Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-III. 2005/2006. Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD : Macro International.

FAFO 2001 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume II

FAFO 2003 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume I

GoH 2004 Decree de la Constitution regarding Communal Section LIBERTÉ ÉGALITÉ FRATERNITÉ DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE RÉPUBLIQUE D’HAÏTI DECRET Me BONIFACE ALEXANDRE PRÉSIDENT PROVISOIRE

Government of Haiti 2010 Action Plan for National Recovery and Development of Haiti

Gravlee, C. C., Bernard, H. R., Maxwell, C. R., & Jacobsohn, A. 2013 Mode effects in free-list elicitation: Comparing oral, written, and web-based data collection. Social Science Computer Review 30:119–132.

Gravlee, Lance Dept. of Anthropology, University of Florida The Uses and Limitations of Free Listing in Ethnographic Research

Hashemi, Syed M., and Aude de Montesquiou. 2011. “Reaching the Poorest with Safety Nets, Livelihoods, and Microfinance: Lessons from the Graduation Model.” Focus Note 69. Washington, D.C.: CGAP, March.

Himmelstine, Carmen Leon 2012 Community Based Targeting: A Review of CBT programming and literature

Hoskins, A. 2004. Targeting General Food Distributions: Desk Review of Lessons from Experience. Rome, WFP).

IRIN 2010 Haiti: US Remittances Keep the Homeland Afloat. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

http://www.irinnews.org/report/88397/haiti-us-remittances-keep-the-homeland-afloat

Kaufman, Michael. 196. “Community Power, Grasrots Democracy, and the Transformation of Social Life.” In Michael Kaufman and Haroldo Dila Alfonso (eds.), Community Power and Grasrots Democracy: The Transformation of Social Life. London and Otawa: Zed Boks and IDRC.

Kolbe, Athena R., Royce A. Hutson , Harry Shannon , Eileen Trzcinski, Bart Miles, Naomi Levitz d , Marie Puccio , Leah James , Jean Roger Noel and Robert Muggah 2010 Mortality, crime and access to basic needs before and after the Haiti earthquake: a random survey of Port-au-Prince households In Medicine, Conflict and Survival

Krishna, Anirudh 2010 “One Illness Away: Why People Become Poor and How they Escape Poverty” Oxford University Press

Lamaute-Brisson, Nathalie 2009 Pour le ciblage des interventions en matière de sécurité alimentaire. Note d’orientation WFP

Lavallee, Emmanuelle, Anne Olivier, Laure Pasquier-Doumer, and Anne-Sophie Robilliard 2010 Poverty Alleviation Policy Targeting: a review of experiences in developing countries.

Lowenthal, Ira 1984. Labor, sexuality and the conjugal contract. In Haiti: Today and tomorrow, ed. Charles R. Foster and Albert Valman. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Lowenthal, Ira. 1987. Marriage is 20, children are 21: The cultural construction of conjugality in rural Haiti. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University.

Lundahl, Mats. 1983. The Haitian economy: Man, land, and markets. New York: St. Martin’s.

Maguire, Robert E. 1979 Bottom-Up Development in Haiti. Washington, DC: The Inter-American Foundation,

Mansuri, Ghazala and Vijayendra Rao 2013 Localizing Development Does Participation Work? International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

Maxwell, Daniel, Helen Young, Susanne Jaspars, Jacqueline Frize 2009 Targeting in Complex Emergencies Program Guidance Notes. Feinstein International Center, Tufts University

McClure, Marian 1984 Catholic Priests And Peasant Politics In Haiti: The Role Of The Outsider In A Rural Community A paper prepared for presentation at the Caribbean Studies Association meetings St. Kitts May 30 – June 3

Morton, Alice, 1998 The NGO Sector In Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction, World Bank Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

MPCE 2004 Carte de pauvreté d’Haïti, à partir des données de l’ECVH (2001)

Murray, Gerald 1977 The evolution of Haitian peasant land tenure: A case study in agrarian adaptation to population growth. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, Department of Anthropology.

Nicholls, David. 1974. Economic dependence and political autonomy: The Haitian experience. Occasional Paper Series No. 9. Montreal: McGill University, Center for Developing-Area Studies

Pace, Marie with Ketty Luzincourt 2009 Cumulative Case Study: “Haiti’s Fragile Peace”

PAM/CNSA 2007 l’Analyse Compréhensive De La Sécurité Alimentaire Et De La Vulnérabilité

PNUD 2000 Bilan commun de pays du PAM, du FNUAP, de l’UNICEF, de l’OMS/OPS et de la FAO. RPP

Richman, Karen E. 2003. Miami money and the home gal. Anthropology and Humanism 27(2): 119–32.

Romney, A. K., S. C. Weller, and W. H. Batchelder. 1986. Culture as consensus: A theory of culture and informant accuracy. American Anthropologist 88:313–38.

Rotberg, Robert I., and Christopher A. Clague. 1971. Haiti, The politics of squalor. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sali, Jamil 2000 Equity and Quality in Private Education: The Haitian Paradox, Compare, 30(2), 163–178, (p. 165) 3.

Schreiner, Mark 2006 The Progress out of Poverty Index TM: A Simple Poverty Scorecard for Haiti

Schwartz, Timothy. 1998. NHADS survey: Nutritional, health, agricultural, demographic and socio-economic survey: Jean Rabel, Haiti, June 1, 1997–June 11, 1998. Unpublished report, on behalf of PISANO, Agro Action Allemande and Initiative Developpment. Hamburg, Germany.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2000. “Children are the wealth of the poor:” High fertility and the organization of labor in the rural economy of Jean Rabel, Haiti. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2004. “Children are the wealth of the poor”: Pronatalism and the economic utility of children in Jean Rabel, Haiti. Research in Anthropology 22:62–105.

Scott, Lucy and Andrew Shepherd 2013 Microeconomic Indicators of Development Impacts and Available Datasets in Each Potential Case Study Country

Sletten, Pål and Willy Egset. “Poverty in Haiti.” Fafo-paper, 2004.

Smillie, Ian 2001 Patronage or Partnership: Local Capacity Building in Humanitarian Crises Published in the United States of America by Kumarian Press, Inc. 1294 Blue Hills Avenue, Bloomfield, CT 06002 USA.

Smith, Jennie M. 1998. Family planning initiatives and Kalfouno peasants: What’s going wrong? Occasional paper/University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies, no. 13. Lawrence: Institute of Haitian Studies, University of Kansas.

Smith, Jennie M., 2001 When The Hands Are Many Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Smucker, Glenn Richard. 1983. “Peasants And Development Politics: A Study In Haitian Class And Culture”. New School For Social Research. Pages: 511.

Steeve Coupeau 2008: 104 History of Haiti. Greenwood Press: Westport Ct.)

UN 1996 Final report on human rights and extreme poverty, submitted by the Special Rapporteur, Mr. Leandro Despouy’ (28 June 1996) UN Doc E/CN.4/Sub.2/1996/13

UNDP 2011 Cash Programming in Haiti Lessons Learnt in Disbursing Cash Suba Sivakumaran (Subathirai.sivakumaran@undp.org)

USAID (United States Agency for International Development) 1983 Haiti: HACHO Rural Community Development. AID Project Evaluation Report No. 49

USAID 1994 Rapid Assessment Of Food Security And The Impact Of Care Food Programming In Northwest Haiti.

USAID 2013 Performance Indicators Reference Sheets for FFP Indicators http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/PIRS%20for%20FFP%20Indicators.pdf

Verner, Dorte 2008 Making Poor Haitians Count Poverty in Rural and Urban Haiti

Based on the First Household Survey for Haiti. The World Bank Social Development

Sustainable Development Division World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4571

WFP (undated_b) Monitoring & Evaluation Guidelines United Nations World Food Programme Office of Evaluation and Monitoring Via Cesare Giulio Viola, 68/70 – 00148 Rome, Italy Web Site: www.wfp.org

WFP 2006a TARGETING IN EMERGENCIES WFP/EB.1/2006/5‐A

WFP 2006b Thematic Review of Targeting in Relief Operations: Summary Report. Ref. OEDE/2006/1

WFP 2009 Targeting in Complex Emergencies, Programme Guidance. Feinstein International Center, Tufts Universtiy

WFP 2013 Basic Guidance Community-Based Targeting

WFP/EB.A/2004/5‐C).

White, T. Anderson And Glenn R. Smucker 1998 Social Capital and Governance in Haiti. In Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction, World Bank Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

WHO 2013. World Health Statistics

http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2013/en/

Wiens, Thomas and Carlos Sobrado 1998 Rural Poverty in Haiti In Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction, World Bank Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

Wiesmann, Doris, Lucy Bassett, Todd Benson, and John Hoddinott 2009 Validation of the World Food Programme’s Food Consumption Score and Alternative Indicators of Household Food Security. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00870

World Bank 1998 Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction (In Two Volum-les) Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

World Bank 2011 Working Research Paper Echevin2011 Vulnerability before and after the Earthquake. by Damien Echevin World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5850. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection.

World Bank 2013 Design & Implementation: Targeting and Selection. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection

Zaag, Raymond Vander, 1999 Encounters Of Development Knowledges, Identities And Practices In A Ngo Program In Rural Haiti Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Geography and Environment Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Zak, Marilyn and Glen Smucker HAITI DEMOCRATIC NEEDS ASSESSMENT May 1989 USAID (United States Agency for International Development) Office of Caribbean Affairs Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean