I have put this brief together with the post-earthquake housebuilding craze in mind. After the 2010 earthquake, international organizations did a lot of housebuilding in Haiti. Yet, there is a whole lot about the topic that seemingly no one at the time was interested in learning. And so here I want to get it down on paper where other researchers can read about it.

First, there’s the issue of the house itself. After the earthquake, international aid organizations gave houses only to women. Men were not given houses. Yet, a house built by a man and gifted to his wife is the single most important ingredient in establishing a family in Haiti. I elaborate below, but here I just want to make the point because it brings up the question: what is the impact on the family of a woman getting a house given to her by someone besides her husband?

Another point I make with this post is the absurdity in the cost of earthquake shelters and houses the international community built in comparison to traditional Haitian houses. The U.S. government got billed an average cost of $5,265 per temporary shelter built for earthquake survivors. A temporary shelter is something that legally can’t last more than three years. They even deliberately built them to rot so that the legal limits regarding the life-expectancy of the shelters were not exceeded (something that a senior OFDA/USAID staff member told me during a job briefing). These costs are many times the cost of a typical rural Haitian house–as seen below– they’re more expensive than any other humanitarian shelter in the world at the time. Much more expensive. The Haitian temporary shelters were almost twice the cost of their nearest competitor, the developed country of Georgia where the UN paid $3,000 in 2009 for winterized cottages; they were five times the $910 cost that humanitarian organizations charged to provide a winterized temporary shelter to Afghanistan war refugees; and they were 18 times the $300 local cost in urban Haiti for materials to build a 12×10 foot shack with a concrete floor, plywood walls and corrugated metal roof. And that’s just temporary shelters. [i]

The permanent homes were even more ridiculous. The NGO Food for the Poor was building permanent houses in Haiti before the earthquake for $2,000 per home. After the earthquake, the U.S. government partnered with Food for the Poor to build 750 of what were essentially the same houses, but at a cost of $38,000 per house, 19 times the pre-earthquake costs. Another major post-earthquake USAID housing project was outside of Port-au-Prince, in a town called Cabaret. USAID spent $53,205 per home for 156 homes. It’s hard to convey the absurdity of these prices. The homes were, once again, little more than garden sheds and in Haiti building materials and labor are cheap. Again, as will be seen below, most Haitians can put together a satisfactory home out of local materials for a couple hundred dollars. [ii] [iii]

With all that said, I begin with a discussion of the role of a house built by a man and given to his wife as the foundation of the Haitian family.

Housebuilding and Building a Family

In Haiti, most couples have traditionally not entered directly into marriage. Rather they enter into a residential union called plasaj. For all practical purposes plasaj was, and still is, de facto, the same as what upper and middle-class westerners consider to be marriage: the couple resides together, they are expected to bear and raise children, and the man and woman have obligations to care and provide for one another. The man must provide income, farming or otherwise, while the woman is expected to perform domestic duties, care for the children and maintain the household. Legal marriage has always been practiced in rural Haiti, but it was something that Haitian couples did after their children were grown, when the couple was in their 40s or 50s, a tradition true not only in Haiti, but throughout the Caribbean (read more about it here).

That said, what this post is about one of the two primary ingredient for social recognition of the plasaj union: housebuilding (the other ingredient is children).

For a union between a man and woman to be considered consummated and worthy of community respect, the rural Haitian man must provide a house for the woman. Even if the couple has children together, the union will not be considered consummated and the woman is not truly ‘spoken for’ until he has provided a house Even if the couple legally marries while in their twenties– increasingly common with the growing influence of evangelical churches –the union will not get the respect of the community, family and friends unless the man has provided a house to the woman.

And no one else can provide the house except the man. A man’s family can help him build the house. But if the woman or her family provide the house, the union is considered vacuous and no self-respecting male would accept such a situation. Indeed, he would be the subject of community ridicule.

Again, what I am describing is not unique to Haiti but rather a consistent feature of conjugal union throughout the Caribbean, such that in a review of twenty Caribbean ethnographies for twenty different Caribbean countries, Keith Otterbein (1965) found that in every case for which there was data (fifteen of twenty islands), the primary ingredient for conjugal union was that men provided a house (see also R. T. Smith 1956: 146; M. G. Smith 1961: 465; Philpott 1973: 120–21, 142; Sutton and Makiesky-Barrow 1970: 310).

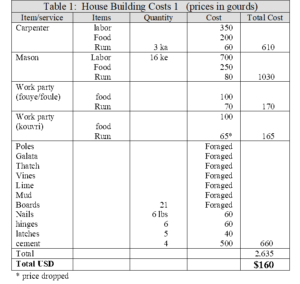

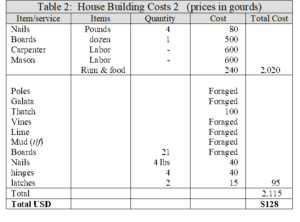

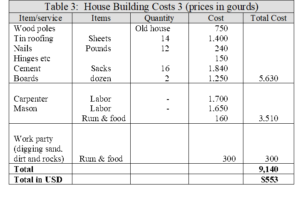

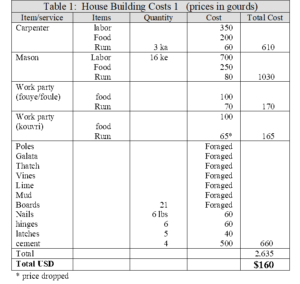

With the preceding in mind here is a short summary of the costs, strategies and materials available for housebuilding in rural Haiti (specifically the Far Northwest). It is based on data I gathered between 1995 and 2000 in rural Haiti.

Housebuilding in Rural Haiti[iv]

The process of building a house usually goes as follows: Branches for house supports and the I-beam that holds the house together are cut from living trees that belong to the man, begged off a friend, or purchased from in the market. For the walls, a man gathers rocks or, if the house is going to be waddle and daub, sticks (galata is a common source of sticks; see below). For plaster, he makes his own lime by cooking lime rocks, or if he cannot find lime rocks, he uses clay which is abundant in the area (preferably a white clay). His wife or future wife, mother, grandmother, sisters, and other female relatives, neighbors and friends will likely carry dirt and sand as needed. The dirt and sand are mixed with lime or clay to make a weak cement. In some areas like La Presque’Ile near Mole St Nicolas, the man may harvest his own roofing thatch or he can use Guinea grass found on State lands. In most areas thatch from the Royal Palm is sold for 2-3 gdes (at the time 16.5 gdes = 1 USD) per bundle and a typical house can be covered with about 400 bundles.[v] The vines that lash the house poles together can be gathered in the bush and the poles that form the roof platform are usually from galata, a very straight branch derived from a kind of sisal plant that is ubiquitous on the dry State lands (kadas). Of course, all the materials can be purchased; the only materials that typically cannot, if necessary, be foraged are the locally hewn boards used to make window shudders and doors.

To build the house: Neighbors and family, enticed by free rum, are assembled to help erect the frame. The main poles are planted several feet in the ground. Other framing poles are nailed to these. At this point the structure is a standard rectangular house skeleton with a simple A- frame roof. (Friends and neighbors typically fade away at this time, returning to help when the roof is put on.). The doors and windows are then framed, most often by a paid boss. The galata branches are laid across the roof and lashed with vine to the house frame and then the thatch, strung on lengths of vine, three leaves to a length, is fastened to the house. Then the walls go up. If the walls are rock, the rocks are cemented together with lime or clay mixed with sand and dirt; if the walls are what is locally called klisay, then sticks are horizontally interlaced between vertical poles. Doors and windows are then framed and the structure is plastered inside and out with pure clay or lime. The jobs for which bosses are typically employed are framing the house and framing the doors and windows; masonry, if the house is stone; and as mentioned, hanging the doors and windows.

Three examples are given below taken from friends of the author. The first man built a small 9.5 x 15 (ft) house. A typical 2 room structure. The man hired both a carpenter and a mason. He was nevertheless able to realize a considerable savings by digging his own clay/mud/plaster, cooking his own lime and gathering vines himself. The man also gathered poles, galata, and thatch from trees growing on his property. He felled a tree for boards and his father, a professional sawyer, sawed the boards free of charge.

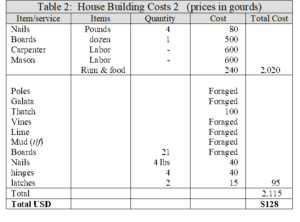

The second man also built his house almost entirely by himself spending 2,115 gdes. He obtained boards by giving a tree to a sawyer friend of his in exchange for half the boards produced. The house was two rooms and a small 10 x 12.5 feet.

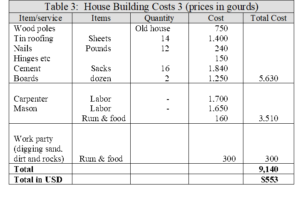

The house listed below is the other extreme of the rural houses. It is not the grand cement houses as seen in small villages, but it is the upper scale of the rural houses and almost all the material and many of the services were purchased. It was built by a woman whose husband was away working in Port-de-Paix but who sent her money to construct the house. It is 10 x 22 feet:

WORKS CITED

Otterbein, Keith 1965 “Caribbean Family Organization: A Comparative Analysis” American Anthropologist 67:66-79.

Philpott, Stuart. 1973 “Remittance Obligations, Social Networks and Choice among Montserratian Migrants in Brittain” Man 3:465-476.

Smith, R.T. 1956 The Negro Family in British Guiana. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd.

Smith, M.G. 1961 “Kinship and Household in Carriacou” Social and Economic Studies 10(1):455-477.

Sutton, Constance and Susan Makiesky-Barrow. 1970 “Social Inequality and Sexual Status in Barbados” Sexual Stratification: A Cross-Cultural View. Alice Schlegel, ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

UN-HABITAT. 2010. SHELTER PROJECTS 2009 Published 2010 Available online from www.disasterassessment.org and IFRC.

NOTES

[i] Below is a more complete list for costs of UN-provided shelters around the world at about the time of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Bearing in mind that the cost in Haiti for a transitionary shelter was $5,265, it highlights the absurdity of the costs in Haiti.

- In Kenya, Dadaab, a permanent shelter was $480.

- In Goma DRC the 2009 costs for a permanent shelter was $930, again 1/5th the cost of the Haitian temporary shelter.

- In 2009 $ 910 in Afghanistan for all costs,( all additional winterization works, project staff, transport, office accommodation, administration, etc.) shelters that are winterized

- In 2009 $930 in Goma USD for shelters, latrines and labor. Project cost per shelter: 250 USD per person, inclusive of operational / support costs.

- Kenya, Dadaab – 2009 Shelter size: 18m2 . 6m x 3m interior space Materials cost per shelter: 480 USD

- In 2009 Somalia in Shelter size: 16m2 Materials Cost per shelter: 620 USD per shelter

- Bangladesh – 2007 – Cyclone Sidr Shelter size: 15m2 Materials Cost per shelter: Core shelters- 1600USD.

- In 2008 Georgia 3000 USD for each winterized cottage. This means that even in Georgia, where per capita income was 12 times greater than Haiti, the cost of a permanent winterized shelter was half what it was costing in sub-tropical Haiti for temporary shelter.

- China, Sichuan – 2008 – Earthquake Materials cost per permanent shelter 9,000 USD -18,000 USD. Note that these were basically new homes.

Source: SHELTER PROJECTS 2009 Published 2010 Available online from www.disasterassessment.org UN-HABITAT and IFRC.

[ii] For the pre-earthquake Food for the Poor houses and costs see, Williams, Grace A. Daley. 2006. An Evaluation of the Low-Income Housing Sector in Jamaica. A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Building Construction Integrated Facility Management (Focus on Integrated Project Delivery Systems) Georgia Institute of Technology December 2006 Copyright © Grace A. Daley Williams 2006. Page 20.

[iii] For the Caracol homes read this.

For the $53,205 USAID homes see, USAID 2013. “Housing Development Fuels New Hope for Haitian Families.”

[iv] Most homes built in Haiti after the earthquake were outside of urban areas

[v] Local names for types of thatch: kokoye, latanye, and pay la preskil. Local names for Grasses: zeb gini, zeb kos, zeb able, and zeb kanna . Roofs have to patched frequently but not uncommonly endure upward of four decades and in at least one instance a grass roof was reported to be 70 years old, albeit it had been added to over the years.