If there’s a milestone year when NGOs began arriving in Haiti that year is 1954, when Hurricane Hazel struck the island. Hazel would go on record as the most destructive storm in Western history. Haiti got the worst of it. Hazel stalled over the country for three days, pounded the mountains and plains with over ten inches of rain. No one knows how many people were killed but arguably more economically destructive than the 2010 earthquake, the storm striped the beans from 40% of the country’s coffee trees, uprooted 50% of its cacao, killed livestock, turned at least one town into a lagoon, and precipitated famine and hunger among the poor throughout the entire country. Haitians would dub the disaster Douz Oktob, the 12th of October, the day the sky cleared and people came out of their homes to assess the damage.

From the Southern coast to the tip of the Northwest, the storm was so devastating that to this day, 6o years later, the event serves as a temporal milestone. Older people often recall when they were born or when they had their first child with comments such as, “the year before Douz Oktob,” or “it was shortly after Douz Oktob.”

It was this year that CARE International, Catholic Relief Services and the Red Cross first showed up. They came with donations from governments and goodhearted Americans and Europeans. They provided relief to untold numbers of needy people. The aid was also marked by what would become a hallmark of aid to Haiti: corruption and siphoning of aid to the elite. In the wake of the disaster rich Haitian ladies dubbed their new mink stoles “Hazels.”[i]

Although the charities had first come to help Haitians recover from a natural disaster, NGOs soon discovered there was plenty more work to be done. Disease, undernourished children, and widespread illiteracy in the face of an inefficient and corrupt public health sector meant that Haiti was one ongoing disaster. Americans and Europeans stepped up their support. By the 1970s Haiti was already among the most aided countries in the western hemisphere. Then, in 1981, U.S. officials decided to bypass the corrupt Haitian government and deliver aid dollars directly to international NGOs. Germany, Britain, and France soon followed and in the words of long-time Haiti expert Robert Maguire, what ensued was “a wave of development madness.” Overnight NGOs were turned into full-fledged US Government humanitarian aid contractors. By 1986, NGOs dominated all state, healthcare, water sanitation, education, welfare, food, agricultural extension, and road construction programs. That same year many NGOs together with the Catholic church, vocally supported the overthrow of the Jean Claude Duvalier regime. By 1987 the regime was gone.

In its place the charity sector continued to grow. In 1990, out of the political chaos and turmoil, a massive welling up of popular support propelled ex-priest Jean Bertrand Aristide to power. A Liberation Theologist who advocated for the poor, Aristide wielded control over one of the largest charities in Haiti: an orphanage, school, clinic, radio station, and community outreach program housed in a 6 story building, the largest structure in midst of the Haitian capital’s a sprawling poorest one and two-story slum, Cite Soley. His closest associates, priests Jean Marie Vincent and Gérard Jean-Juste were also liberation theologists steeped in aid and managing vast networks of charitable institutions fueled by international donations. It can be said without exaggeration that they were the purest expression of the Haitian adaptation to what had become the most important industry in Haiti: charity. And they were not alone.

In 1991 when in the wake of the coup that deposed Aristide for the first time, George Bush ordered the evacuation of all US missionaries, 90% of them heeded the warning and fled; 20,000 of them in all, one for every 400 Haitians (some doing ridiculous things, like getting in boats and fleeing to the sea). When Aristide came back in 1994, 20,000 UN troops came with them. And so did the NGOs. They poured back into the country. Together with their home governments (the US and the EU), they then supported Aristide in disbanding the army, effectively removing any teeth left to the Haitian State. All that remained for security was a fledgling 2,000 member police force and 20,000 UN soldiers. Haiti had become a country of NGOs. In 1998 Gerald Murray, one of Haiti’s more consulted foreign consultants and who had worked in the country since 1972 would justifiably write that, “Haiti probably has more NGOs and foreign missionaries per square foot than any country on the planet.”

Granted, it’s a novel argument that charity was driving the decline of the Haitian State. But de facto, that’s exactly what was going on. NGOs and the UN organizations–World Food Program, UNICEF, UNOPs, UNDP, all of which function exactly like NGOs, including charity drives and private donations–were receiving 95% of aid. Aristide himself was as or more dependent on his charity for political survival than taxes. Seven years later, in 2001 the international community was fed up with Aristide–who by this time was not only president but also head of the Aristide Foundation, the largest domestic NGO in the country. This time, instead of a trade embargo, the international community launched an “aid embargo.” It crippled the government but failed to destroy it. A military invasion of 200 insurgents then took over half the country. Once again, many of the International NGOs and overseas missionaries pulled out. In the meantime Aristide became a victim of his own plot: with no army to defend him he too soon left (some say was kidnapped). Haiti again became a ward of the international community. And once again the NGOs and missionaries came back stronger than ever. And with them, once again, came UN troops.

Now weaker than ever and fast becoming a narco-state, Foreign Policy magazine put Haiti at the top of its list of “failed States.” The presence of NGOs and missionaries reached such proportions that even before the earthquake observers began to refer to the country as the Republic of NGOs. In 2009, the United Nations would make Bill Clinton its Special Envoy to Haiti. Already de facto leader of the NGO world by virtue of his Clinton Foundation’s Global Initiative–a program dedicated to pulling together efforts of all major NGOs and International organizations, it’s difficult to resist the conclusion that the UN had appointed their own Haiti shadow president.

But, at about the turn of the millennium, in the midst of all I am describing, while the NGOs by design or simply consequence were consummating their position as custodians of the Haitian masses, a series of disasters reminded everyone of why the NGOs had come in the first place.

On May 25th 2004, people on the Haitian-Dominican border woke to what some described as the sound of an oncoming freight train. A moment later doors and entire walls were exploding as an avalanche of rocks, sand and trees obliterated their homes. The flash flood killed more than 1,660 people in the mountains on the Haitian side of the border and another 1,000 or more Haitians and 652 Dominicans on the Dominican side. Most drown or were buried under as much as 20 feet of gravel. When it was over there were seven new lakes on the Haitian side of the border; under one of them was an entire town. Four months later, in September, Tropical Storm Jeanne sent another avalanche of water, mud, gravel and uprooted trees raging down the eastern side of Mon Belans, above Haiti’s third largest city, Gonaives. The torrent blew out roads, bridges, and irrigation works before smashing its way through Gonaives, where it killed 2,400 people and left 80% of the city’s 140,000 survivors stranded on rooftops. Foreshadowing the 2010 earthquake to come, a delegation from the Canada’s National Coalition for Haitian Rights-Haiti (NCHR) described the scene,

Four (4) days after the flooding, water still covered the majority of the streets in the city. The smell upon entering the town was rank – a mixture of garbage and death as the decaying bodies of cows, pigs, goats, dogs and even a horse littered the street. Entire buildings lay in rubble – walls demolished, vehicles pushed into houses and/or submerged under water, entire homes pushed over and/or washed away. Where the water had receded, thick layers of mud remained.[ii]

The US response was to donate several 100 million dollars for disaster preparation and watershed management, for it was clear more floods would come. They would bring with them more destruction, and more people would die. In 2008 those fears were confirmed when a series of four other storms killed 1,000 people, destroyed 22,702 homes and wiped out one-third of Haiti’s rice crop. Most of this came with Tropical Depression Hanna which killed another 500 people in Gonaives and once again left the population stranded rooftops. [iii]

But it wasn’t just floods. Droughts too were getting a great deal of attention, particularly in Haiti’s Northwest. In 1992 increasing malnutrition brought on by the 2-year drought precipitated the massive 18-month USAID-CARE feeding program in which daily meals were given to more than 800,000 recipients. Another drought in 1997 led to a visit from a group of US congressmen. I was there when they flew in on a UN helicopter. Instead of landing outside of town as was customary, the important delegation choppered straight into the town, landing on the soccer field and kicking up a dust storm that sent people running for cover and blew the roofs off of three houses.

NGOs, government officials, and disaster relief workers blamed the floods and droughts on extreme deforestation. As the argument goes, the lack of trees leads to a raising of temperatures thereby causing increasingly longer dry spells; when the rain finally does come, it rolls off the desiccated soil and causes flash flooding. To combat the scourge the international community poured money into Haiti. But other problems sabotaged the undertaking. The programs were rife with corruption. Pork barrel US policies earmarked the money for what came to be known as ‘beltway bandits,’ massive US contractors with their multistory mirror windowed offices in Washington and their teams of lobbyists prowling the halls of Capitol Hill. Back in Haiti things were clearly getting worse.

The aid agencies and embassies increasingly sounded the alarm. During the 1990s millions were spent setting up Early Warning Livelihood Security Systems to detect famine brought on by drought. The most costly one–that included Jean Rabel, where the congressman had choppered in and blown the roofs off the house–was an absurd flop. Having participated in it, lived in the area, and sat in on Port-au-Prince donor meetings, I can attest to it never functioned neither in the field or the boardroom. Based on a more than US$1 million of research, it would not even survive the scrutiny of the bureaucrats who funded it. By 2005 they were working on a new Early Warning System—one that didn’t function well either. Yet, with the approach of every hurricane season a wind of panic would sweep through the halls of NGOs. They called for more donations, and more US government money.

But the fact was that while Haiti could certainly do with some more trees, droughts were certainly a major problem, and hurricanes are menacing fact of life, they were not the crux of the problem. There are plenty of ancient deforested countries on earth—Egypt, Israel and Greece are three of them. Moreover, natural disasters of this order were nothing new. Hurricanes, floods, and droughts had taken a much greater toll in the past than in recent decades. In the 28 years spanning 1980 – 2008, 65 hurricanes, tropical storms, and thunderstorms killed 8,165 people in Haiti. In comparison, three storms killed at least 11,000 people in the 28 years between 1935 and 1963–before most aid agencies arrived and when Haiti had a population one-third its current size.[iv]

Drought was nothing new either. We know that severe droughts have been hitting the island at least since the first Spanish colonists arrived in the 15th century. It’s an unfortunate climatic feature of the entire Caribbean and peasant livelihood strategies and crops throughout the región are adapted to it. The French Geographer St Mery who visited in 1780 would describe local farmers experiencing, “long and distressing dry spells.”[v] To adapt to this, farmers plant an array of remarkably drought-resistant crops. In times past, when the situation really got bad peasants ate drought-resistant manioc roots and yams and they boiled green mangoes. They fed their livestock dried stalks from the pigeon pea plant and stalk of sugar cane, an almost indestructible plant that sends its roots 27 feet underground. Peasants would go to islands such as La Tortue—which has 10 times the rainfall and that is only 10 miles from the mainland–and bring back manioc and a type of raw sugar-paste called rapadou. Later, as the aid agencies came with what they called sinistre, imported food aid, the peasants would sometimes name the crisis after the blan in charge of distributing the relief.

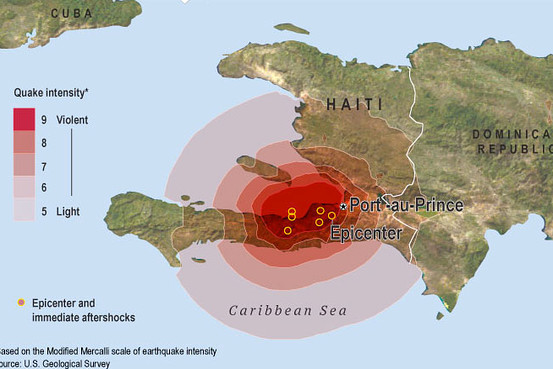

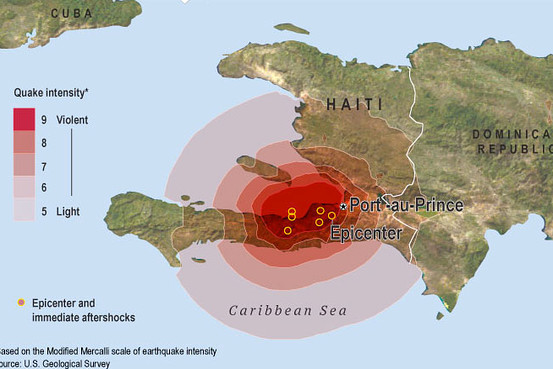

Nor should anyone have been surprised with seismic activity. Severe earthquakes struck Haiti in 1564, 1684, and 1691. In 1751 Port-au-Prince, not much more than a town at the time, was completely destroyed. Another earthquake destroyed it again 1770. In 1842, a massive earthquake killed some 10,000 people in the North of Haiti and the neighboring DR.[vi] All three of these earthquakes were so powerful that in areas of high sediment the shaking liquefied the ground swallowing buildings, livestock and people. In the city of Cape Haitian stories have been passed down of people sinking into the dry earth, found later only by tufts of hair sticking out of the dirt.

Although less well documented, the Northwest of Haiti has also suffered recurrent earthquakes. Using Church records, I calculated that since the early 1600s earthquakes have hit the Northwest city of Port-de-Paix on average every 43 years—they’re about 30 years overdue right now. On the Dominican side of the border, a 1946 earthquake that registered 8.1 on the Richter scale generated a thirty-foot high tsunami that killed 1,790 people.

So getting to the punch line, Haiti does indeed have the bad luck of being on an island that seems geologically damned. And the fundamental nature of natural disaster and the threat it poses has indeed intensified radically in recent years. But the reason was not so much deforestation. The real threat was population growth and, more to the point, uncontrolled urbanization.

In the half-century before the 2010 earthquake, Haiti’s population had tripled, going from 3 million in 1950 to 10 million in 2009. Over that same period of time people migrated in mass to urban areas. Whereas greater Port-au-Prince had 250,000 people in 1950, by year 2000 it had at least 2.7 million people. The vast majority of them lived in unplanned neighborhoods on vulnerable flood plains, ravine bottoms, and unfortified hillsides. Most lived in homes that would never have passed even the most liberal of building codes and built of bone-crushing cement and iron re-bar, materials that are relatively new to the island and about which Haitian semi-skilled artisans who build them think they understand but in reality know little.

Yes, Haiti, she’s been beating the odds. But then, we already knew that. Even before the earthquake everyone with any knowledge of the country and the most basic understanding of geology already knew that time was running out. That was surely part of the reason for the increasing sense of panic among NGO workers. Haiti was due for a major seismic disaster. And everyone in Haiti who bothered to stop and think about it knew it.[vii] It had been known it for a very long time. When US Secretary of State William Seward visited Port-au-Prince in 1866 he had this to say,

Almost all buildings are of but one or two stories in height. The earthquakes have determined the character of the architecture. There are no brick or stone buildings of several stories, as with us, as the earthquakes would infallibly shake them down on the heads of the occupants. The wooden frame may not only shake, but even rock to and fro considerably, without serious damage. The safest material for all houses in such a climate is wood. Residents told me they remembered no case in which a wooden house was destroyed by earthquake, even when brick ones were tottering and tumbling into fragments. [viii]

Geologically speaking, nothing had changed. In 1999, I and many people in Port-au-Prince woke to rattling dishes and we were reminded that the city is on a series of faults. And in the week of September 28th 2003, while Aristide was struggling, two noticeable tremors precipitated a near panic. Port-au-Prince’s Radio Metropole announcer reported that “the seismic faults under Port-au-Prince are long overdue for an earthquake.” Haiti’s Minister of the Environment, Webster Pierre–soon to be deposed along with Aristide– warned that, “Sooner or later Port-au-Prince is going to get hit.” On the 30th of September Radio Metropole radio said that, “The government should inform the public in detail about the risks of an earthquake.” And Haitian geologist Claude Prepti warned that “It is urgent that an education campaign is launched to raise awareness” As if to punctuate the point, on October 5th another tremor resulted in 14 deaths. The calls of alarm increased. Five days later, on October 10th, in a meeting of Haitian Engineers and Geologists, the Director of the Bureau of Mines, Geffrard Jean, repeated that “a major earthquake could hit at any moment.” Other participants warned that high-risk zones are Canape Vert, de Bourdon, Delmar, Carrefour Feulle, precisely areas that would suffer massive damage 7 years later. The bureau of mines distributed to seminar participants summaries of the measures that individuals should take in the case of an earthquake and urged preparation. The NGOs were mum. And that was it. At least, for the moment.[ix]

It was the very next year that Gonaives was hit by the flood-like avalanche of rocks, mud and uprooted trees giving everyone a glimpse of the extent of disaster that could befall in the case of an urban calamity. And then in 2005 the ground in Port-au-Prince was rocking again with a six-month spate of tremors that culminated on May 11tth 2005 at 9 pm when a 3-second tremor registered 4.1 on the Richter scale. It caused $100,000 worth of damage to the Port-au-Prince electric grid and, more ominously, cracked walls in L’ecole Nationale d’Infirmieres,” the Nurses School where four and one-half years later more than 100 nurses and staff would be killed in the 2010 earthquake. The main staircase leading into the building split on both sides. Walls and ceilings covered with cracks. The newspaper Le Matin, noted, “The student nurses say that they are alarmed by this sword of Democlès hanging over their heads.”

Five days later, on the 16th of May 2005 another tremor hit and once again more meetings and interviews and articles and commentary, the conclusions of which were summed up in an official meeting as, “all the conditions are ripe in the capital for a major natural disaster.” The panic was not lost on the US Embassy. On the 25th of May an embassy official sent out a cable, “The last thing Haiti needs now is an earthquake,” and “A more severe earthquake would be catastrophic, as the government of Haiti is unprepared to handle a natural disaster of any magnitude.” The embassy scheduled an OFDA [Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance] team to come to Port-au-Prince in June [2005], “to help the embassy coordinate its disaster preparations, and to try to jump-start [Government of Haiti] and donor coordination and planning.” [x]

Once again, that was it. The NGOs were essentially mum. The Embassy apparently dropped the issue. Nothing more. Nothing that is until September 1st 2008 when in the space of 11 days three tremors rocked everyone awake again. On September 25th 2008 Phoenix Delacroix would write in the Port-au-Prince newspaper Le Matin, “The issue of seismic threat in Port-au-Prince is a hot topic.”

It has been debated in recent days by many people, including senior intellectuals. The conclusions are unanimous: ‘Port-au-Prince may well be transformed overnight into a mass of ruins after a violent quake.’”

The predictions were frighteningly precise. Dieuseul Anglade, Head of the Bureau of Mines and Energy, told the press that,

For two centuries, no major earthquake has been recorded in the Haitian capital. The amount of energy accumulated in the fault, puts us at risk of an earthquake of 7.2 magnitude on the Richter scale… It will be a catastrophe of biblical proportion.

Haitian Engineer Gerard Luc went on Radio Metropole and put into perspective the proportions of the calamity when it did hit, warning that with the poor construction standards and the use of low-quality local sand in cement mixtures could result in as much as 70% of local Port-au-Prince buildings being destroyed. Trying to make people understand, former professor at the Geological Institute of Havana, Patrick Charles spoke on Radio Metropole,

Thank God science gives us tools that can predict these kinds of events. Our capital is at the mercy of Mother Nature; the clock is ticking. A major disaster is looming over our heads…The problem is posed in all its acuteness. The warnings are regularly sent. But timely and appropriate measures have yet to be taken….The authorities are obliged to take specific measures… we must act swiftly. The countdown has begun. Nature asks us to be accountable. We must act to save what can still be.”[xi] [xii]

Other articles in Le Matin by geologist Claude Prepti caught the attention of Greg Groth at the US Embassy. With 2005 apparently forgotten, Greg would begin his correspondence by unwittingly repeating almost verbatim what the other embassy official had written three years earlier, “that’s all we need: earthquakes!” A series of correspondences ensued. This time embassy officials decided to do something. At the cost of US$200,000— little more than the annual salary for one of the embassy officials who came up with the idea– four seismic monitoring stations were planned for installment. They were being installed when the quake hit two years later.

NOTES

[i] Heinl, Robert Debs and Nancy Gordon Heinl 1996. Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People 1492-1995.

[ii] By National Coalition for Haitian Rights-Haiti (NCHR) September 22nd, 2004.

[iii] Jeffrey Masters, Ph.D. — Director of Meteorology, Weather Underground, Inc. “ Damage was estimated at over $1 billion, the costliest natural disaster in Haitian history. The damage amounted to over 5% of the country’s 17$ bil gdp”

[iv] Specifically in 1935 more than 2000 were killed in an unnamed storm, in 1954 Hurricane Hazel killed over 1,000 people and left the entire country devastated on a scale arguably exceeding the earthquake, and in 1963 Hurricane Flora killed over 8000 Haitians and left similar waste in its path.

[v] Moreau (1797) Moreau notes that local farmers “knew long and distressing dry spells” (mais on y connaissait aussi de longues et affligeantes sécheresses: ibid: p 724).

Moreau, St Mery 1797 Description de la Partie Francaise de Saint-Domingue Paris: Societe de l’Histoire de Colonies Francaises, 1958 v. 2

Scherer, J. (1912). “Great earthquakes in the island of Haiti”. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2: 174–179.

Boswell, James (1770). “France”. The Scots Magazine 32

[vi] The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, Volume 48, from pg 262, ‘Haiti or Hispaniola’, by Major R. Stewart, 1878)

[vii] So the explosive growth in building on vulnerable ground and the fact that the country was riddled with fault lines and situated square smack in the middle of the Western Hemisphere’s hurricane belt meant that Haiti had been lucky. As the urbanization took hold, the wealthy retreated up the hillsides, staked out and legally titled new residential lots where they built splendid homes and surrounded them with fortified walls. Meanwhile the majority of the population thrived on the informal economy, with an entirely different land tenure system and began constructing homes with shoddy and what was, given the situation eminently dangerous building materials. It’s tentacles wrapping around the wealthy compounds, filling the green space, the ravines and flood plains.

[viii] Reminiscences of A War-Time Statesman and Diplomat 1830-1915 By Frederick W. Seward Assistant Secretary of State during the Administrations of Lincoln, Johnson, and Hayes G. P. Putnam’s Sons New York and London 1916 BY ANNA M. SEWARD

[ix] Radio Metropole 13th and 14th of October 2003

[x] Haiti: US Embassy Knew of Earthquake Vulnerability Sunday, June 19th 2011 Dan Coughlin.

[xi] “The principal fault in the north has not released energy for 800 years…. Three meters of …. Slippage.. When it goes we can expect massive destruction, Tsunami…”

[xii] Patrick Charles also said that , “The problem is posed in all its acuteness. The warnings are regularly sent. But timely and appropriate measures have yet to be taken….The authorities are obliged to take specific measures to protect these areas,… we must act swiftly. The countdown has begun. Nature asks us to be accountable. We must act to save what can still be.”

http://www.ayitigouvenans.org/earthcanes.html

Ayiti Gouvènans (AG) Haiti: Threat Of Natural Disaster/High Seismic Risk Over Port-Au-Prince. On September 25, 2008, Le Matin, by Phoenix Delacroix