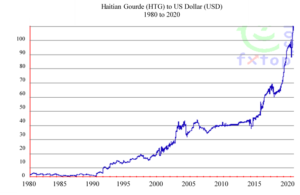

Beginning in 1912, the Haitian Gourde (HTG) was legally fixed to the US Dollar: 1 USD = 5 HTG. The standard was abrogated in 1989 and the HTG was allowed to float freely in value. And it has done a lot of floating.

The number of Haitian Gourde (HTG) to the US Dollar (USD) went from 1 USD = 5 HTG in 1989 to a recent 2020 high of 1 USD = 123 HTG, a change by a factor of 24. Considering only the period 1999 to 2015, the number of HTG to the USD more than tripled, going from 16 to 57 HTG = 1 USD. Since then, in the past five years, it has doubled to a recent 123 HTG per 1 USD. About half of that increase occurred in the first six months of 2020.

The reason that it makes sense for analysts to keep a close eye on the USD to the HTG is because the Haitian economy is closely linked to the US economy, its major trading partner, source of some 50% of food staples, such as rice, and many durable goods. Even in the case of cell phones and motorcycles imported from China, the goods must be purchased with foreign currency, the value of which is best approximated in US dollars. When Haiti’s Gourde depreciates in value vis a vis the US dollar, the cost of everything in Haiti is not far behind. First comes those items purchased overseas: imported foods, durable goods such as batteries and plastics, and quite literally anything manufactured or that has imported ingredients. The impact of increasing prices is softest for those who are fortunate enough to have family in North America–the source of more than 50% of the GDP in the form of ~US2 billion in annual remittance from expatriate Haitians living in the US.

Those being paid in Haitian Gourdes, such as domestic and factory workers, and those living exclusively off the local economy, such as farmers and market women, are the least fortunate. It’s a boon for the factory owners who sell their products in foreign currency and humanitarian organizations that pay their national employees in local currency, and even the government that is getting assistance in foreign currency but paying staff in Haitian Gourdes. These employers enjoy the protection of contracts that do not recognize pay in any currency but the Haitian Gourde, and they typically delay modifying the contracts to account for the inflation until the contracts expire or employees refuse to work for less than living wages. Eventually, most prices and pay will catch-up, but there is a definitive lag at the very end of which are those Haitians who are the poorest, the most rural, and the most entrenched in the local economy.