This is a chapter from a book that I am wrote, the Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle (2017). I originally published as it is here on Open Salon in 2011. I think it’s important because it summarizes the role that the mainstream media played inciting panic over insecurity after the earthquake. Anyone interested in the impact of that panic should consult the book and read the chapters on the rescue and emergency medical effort.

January 14th 2010. It is day three after the earthquake. Ben and I are at the airport, on the tarmac, helping soldiers of the 82nd airborne load thick, heavy metal plates into the back of my pickup truck. I pick up an armful and heave them into the back of the truck. Then it occurrs to me, “what the hell are these things?”

“Body armor,” Ben says.

I was beginning to understand that the rescuers, US&R and otherwise, feared a break down in society. No one had actually come right out and said it, not to me. But from the first moment it had been there. At Joseph’s house, on the morning we arrived, we sat under the veranda, next to the swimming pool, the sun rising and as we ate poached eggs, bacon, and sliced mangos. Joseph turned on the portable communications radio from the Embassy, set it on the table, and as we ate we listened to the radio squawk out an air of panic and flight. The Embassy security personnel were organizing an evacuation.

“What are they so afraid of?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Joseph replied, spearing a hunk of mango with his fork.

All foreign embassy personnel and their families had to leave. An hour after breakfast Joseph and his wife and children were told they had to evacuate as well. Led under armed escort to the Embassy, Ben and I followed in my truck, feeling akward that we had driven into Port-au-Prince to help the injured and trapped and now were riding along with uninjured US evacuees. We didn’t know what else to do. We needed to attach ourselves to some group that was here to help. The Embassy seemed like it would be the best place to find them.

As I recounted, we helped with their luggage and then stood there in the Embassy parking lot, watching, as the Americans pulled out.

Now, loading body armor into the back of my truck for one of the US’s most elite fighting forces, I am beginning to understand that fear is the reason the embassy personnel evacuated. Fear is the reason why we had abandoned the nurse’s school the day before. Broken arrow, the Chief had called in on the radio, as if the crowd had been hostile. Fear is also part of the reason why so many rescuers were huddled behind guarded gates, focusing on the same three buildings while thousands of people were still trapped elsewhere in collapsed buildings and thousands of injured desperately needed medical care. And fear must be the reason why all this military hardware and these soldiers around us are setting up base camp behind a ten foot fence. Fear must be why they are walking around in the near sweltering heat with 80 pounds of gear strapped to their bodies and machine guns swung over their shoulders. And fear is one of the reasons why during these first 72 hours after the earthquake, the most important moments when people can be pulled from the rubble, none of the aid workers or even the UN troops will go into the downtown area to the poorest barrios, to the areas where the damage is most severe and the people most need help. The press had played a big part in creating that fear.

*****

The first reaction from the press was an appropriate one. On the 13th of January, the day after the Earthquake, most newspapers drew on their Reuters and AP wire sources and headlines around the English speaking world simply read,

“Haiti Earthquake, Thousands Feared Dead.” (ABC, BBC, AOL, 13th of January)

But by day two, January 14th, the tone had changed,

“Gangs Rule Streets of Haiti.” (CBS, January 14th)

“Gangs takeover Port-au-Prince.” (The Washington Post, January 14th)

“Central Business District Resembles Hell On Earth As Bodies Pile Up And Armed Men Battle Over Food, Supplies.” (CBS New York, January 14th)

“Haiti: Rape, murder and voodoo on the Island of the Damned” (The Daily Mail, January 14th)

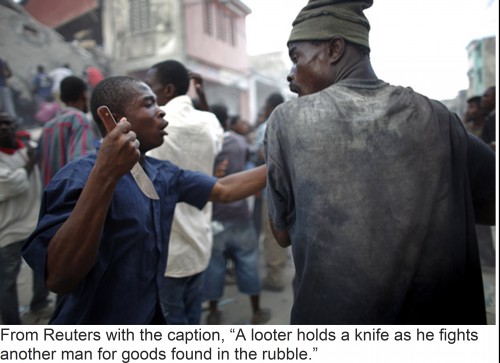

Otherwise responsible journalists such as AP’s Jennifer Kay and Michelle Faul wrote of ‘machete-wielding young men who roam the streets, their faces hidden by bandanas.’ English speaking Newspapers around the work repeated it: Boston Globe, Northwest Herald, Australian, Huffington Post, Toledo Blade, Hindu News, Star, Free Republic as well as CBS News and ABC News.

London’s Telegraph took it even farther and in an article written by Aislinn Laing and Tom Leonard — who were not even in Haiti at the time but were still in neighboring Santo Domingo—declared, “Law and order began to break down in Haiti as “constant” gunshots heard across the capital and shops looted.” And in another dramatic summation that would get repeated worldwide in major newspapers and broadcasts, Shaul Schwarz, a Time Magazine photographer told Reuter’s that, ‘It’s getting ugly out there. Survivors are making barricades out of bodies.”

The problem was that what the press was reporting was not true. I am not saying there was no violence. What I’m saying is that it was emphatically not what the press was saying it was.

It was not gang members who were shooting. It was police and security guards preempting pillagers with warning shots and it was frightened locals and foreigners alike stepping out their back doors and shooting into the air to scare off looters and bandits– real and imaginary. And yes, at least a large segment of the impoverished population of Port-au-Prince was doing what people in New York City, Montreal, or Paris would have been doing if they had the opportunity: they were looting. It made for great pictures. Black people scrambling for goods in streets choked with a haze of dust, many of the looters young men, bandannas wrapped around their faces, And yes, in their hands many carried machetes. But the bandannas were not to hide faces but to filter the dust and stifle the stench of decaying bodies. And the machetes were not for killing, they are the impoverished Haitian’s all purpose tool– for most, their only tool–and they were using them to dig through the rubble, cut and pry and they were also freeing a lot of trapped people in the process. It was not Armageddon, not free-for-all violence. Indeed, the irony as I will show below and as many Haitians already knew, was that it had been a very long time since Port-au-Prince had been so safe.

*****

We’ve moved the body armor and now Ben and I are standing on the airport tarmac looking at two helicopters. They are about 100 yards away from us. They are monsters. Their blades are turning and their motors thump the air. They are so powerful that you can feel them thumping. Ben is close to my ear, “they’re Chinook CH 47’s,” he is shouting, “Soldiers call them ‘shit-hooks.’ They can pick up a semi-truck and fly away with it.” He also tells me that they burn about 350 gallons of fuel per hour. They’ve been sitting there, engines running, for at least a half hour. Ben and I start calculating. A sergeant cuts in. “There’s a meeting.”

A moment later we’re huddled up on the tarmac, the entire unit of some 40 paratroopers. We have to strain to hear over the thumping of the helicopters. The Lieutenant is hollering. He is telling us, “The plan is to fly out to identified spots. When the helicopter puts down the translator from the State Department”—that’s me—“he is going to be on the bullhorn telling the population to stay back.” Then he explains, “three of the soldiers are going to jump out. They are going to go into a three man triad formation with their guns pointed at the people.”

This was serious.

*****

There were voices of reason. When the earthquake struck freelance journalist Ansel Herz was in his second floor apartment, in a middle class neighbor of two and three story concrete buildings. As the building his was in shook and swayed with increasing intensity he staggered to the balcony and positioned himself to jump to the roof the house next door. The earth quit shaking.

Twenty-two years old, fresh out of college and, for those who know him, an impressively cool character, Ansel pulled himself together, shouldered his camera, and walked down the hill and into the city below, alone, at night. He went to the cracked and broken National Palace. He went into the abandoned penitentiary. He walked over to Cite Soley, a neighborhood that in 2006 UN security forces labeled “among the most dangerous on the planet.” Two days later, Ansel tried to tell the world that,

In the day following the quake there was no widespread violence. Guns, knives and theft weren’t seen on the streets, lined only with family after family carrying their belongings. They voiced their anger and frustration with sad songs that echoed throughout the night, not their fists.

Six days into the rescue effort Paul Hunter of CBC, also on the street for the entire week, reported,

The immediate expectation after the earthquake was that Haiti would quickly descend into rioting and violent mayhem.

That has not happened.

Yes there have been reports of looting. . .

And, yes, there have been reports of occasional gunshots. But the fact is, Port-au-Prince has been full-on peaceful.

CBC’s constant experience here has been to be welcomed warmly by everyone we’ve encountered —be it in tent cities or amid the rubble of downtown streets, and both day and night.

It’s a singularly spiritually uplifting aspect to the nightmare of everything else here.

Few other journalists were listening.

*****

Ben and I are now on the other side of the airport tarmac sitting next to the airborne soldiers. A crew from CBS’s 60 minutes has just discovered us. They are embedded with the 82nd Airborne and for the past three hours they’ve been doing the same thing we have, following the soldiers around the airport tarmac thinking that at any moment they are going to board a helicopter and fly out with supplies and deliver them to some portion of the desperate and devastated population of Port-au-Prince. One of the editors is talking to Ben. He tells her that I am an anthropologist who has worked in Haiti for 20 year and is now walking us over to meet the rest of the crew. I am assuming that it is so that I can share my insights on the situation. I definitely have something to say.

“This is a big problem,” I’m saying as we walk, eager that I might be able to set the record straight, “someone has to tell people there is nothing to fear. The rescuers and aid workers have to get out there and help.”

I meet the crew. I have no idea who they are. I haven’t seen an episode of 60 Minutes in at least 20 years. But I know this is big: 60 Minutes is the most successful broadcast program in the history of U.S. television (42 years on the air, 78 Emmys). One of these folks is going to be talking to the American public in a few hours. He or she is going to be giving the world a message. That means they can wake everyone up to the security issue, specifically that there isn’t one. “People aren’t understanding what’s going on,” I’m telling them. And all the while I am thinking, this is my chance to have an impact. We can end this panic. “There is no security issue,” I am trying to sound as professional as I can. “Port-au-Prince has never been safer.”

There is a large heavy set, light skinned man sitting there. He seems to be the boss. And he seems impatient. He doesn’t like what I am saying. Something isn’t right. He cuts in, “Someone,” he says deliberately, with the weight and authority of a seasoned newsman, “shot at CBS crew last night.”

“That’s bullshit.” I blurt out and then try to back peddle, to explain, professional tone, “Maybe they simply misunderstood. Maybe someone was firing in the air. The police?” But there is nothing I can say. I should have asked him for details. A moment later I find myself talking to the side of his head.

******

That same night, on the 15th of January, CNN anchor Sanjay Gupta (MD) and a film crew where recording at a field hospital when the Belgian medical team that was caring for the patients began packing up their belongings. The Belgians loaded everything in vehicles and then, with a UN military escort, they departed. According to Sanjay Gupta, they left behind “earthquake victims writhing in pain and grasping at life.”

Why? Security concerns.

Everyone, including Retired Army Lt. Gen. Russel Honore, head of the 2005 Hurricane Katrina relief effort, was appalled: “I’ve never seen anything like this before in my life” Gen. Honore told the press, “They need to man up and get back in there.”

CCN anchor Gupta was the only doctor who remained. He and the CNN crew cared for the wounded throughout the night. At 3:45 a.m. Gupta twittered: “pulling all nighter at haiti field hosp. lots of work, but all patients stable. turned my crew into a crack med team tonight.”

Hats off to Gupta and the CNN guys. They are heroes–they would get no awards. And whoever ordered the doctors to leave should be reprimanded. As Lt. General Honore said, “I find this astonishing these doctors left. People are scared of the poor.”

But the disgrace in all this was not so much that aid workers were afraid. Anyone who read the headlines would have been afraid. The disgrace was that the press and, more ominously, the US military were causing the fear. The message that Armageddon had descended on Port-au-Prince had been rocketing around the world and coming back to Haiti to scare the hell out of everyone. And it would get worse. The next day, 16th of January, four days after the earthquake,

“Port-au-Prince looting worsens, turns violent” (Vancouver Sun, January 16)

“Machete-wielding thieves have begun roaming the streets of Haiti at night.” (Telegraph, January 16)

And as if there was some kind of secret slaughter going on–conjuring up images of Rwanda– CNN’s Anderson Cooper and Ivan Watson, reported

”Mass grave found outside Port-au-Prince” (CNN, January 16)

The most powerful military force on the planet was taking all of this very seriously. On the 17th of January General Ken Keene, chief of the U.S. Southern Command announced that,

“We are going to have to address the situation of security. We’ve had incidents of violence that impede our ability to support the government of Haiti and answer the challenges that this country faces.”

and

“Providing humanitarian aid requires a safe and secure environment, and, violence has been increasing,”

And, the natural conclusion,

“Our principal mission is humanitarian assistance, but the security component is going to be an increasing part of that. And we’re going to have to address that along with the United Nations, and we are going to have to do it quickly.” (US Southern Command Press….)

Never mind that Keene had probably been getting much of his intelligence from the Press itself, the press now picked up what the General was saying and blamed the slow pace of the aid effort on the violence.[iii]

Violence in Haiti Hindering Aid Work (AP article repeated on BBC, CBS, Fox, The Lancet, The Star, Boston Globe; Huffington Post; Yahoo and ABC, January 17th)

Violence stalls aid to Haiti (The Star-Toronto: January 18)

“Loot mob anarchy holds up Haiti earthquake aid” (The Mirror, the January 18)

On the same day, Anderson Cooper, who had been ernstly thrilling people around the globe with images of violence and reports of ‘mass graves,’ illustrated to the world his own fearlessness and heroicsim with his piece entitled,

“In The Midst Of Looting Chaos” (CNN January 18, 2010)

In Cooper’s CNN clip there is a violent melee in which it is not really clear what’s going on. But with Cooper explaining, viewers learn that looters are battling over boxes of candles. A piece of concrete strikes a 10 year old boy in the head. Cooper goes into action. He wades into the the melee, scoops the bleeding boy into his arms, and rushes him to the safety of a wooden table. All caught on film. A few moments later the boy was gone. Cooper doesn’t know what happened to him, if he survived, who struck him, or why.

What the Cooper story illustrates, beside that Cooper is fearless, is something that should have struck viewers as bizarre. In the middle of all this violence and fighting, machete wielding bandits with faces hidden behind scarves, in the kidnapping capital of the Western hemisphere, the foreign press seemed bullet proof. They walked about with cameras rolling, taking pictures of the people holding knives and machetes, waded into the midst of looting melees, interviewed people, and generally did and went wherever they pleased. Not a single one got attacked, injured or threatened. Moreover, with the exception of at least one vigilante act—which is typical in Haití as the people have learned to take justice into their own hands (one reason for low levels of absolute violence I will describe shortly)–the journalists documented one person getting hacked up or stabbed, one (they took pictures of that too). Yet through selective and sensational reporting focused on a few areas of looting—almost entirely non-violent looting—the press went right on sending out an image of Armageddon. Indeed, as seen, they began to blame the widespread “violence” on the aid not getting out. And now the U.S. Military was poised to declare marshal law and move troops into the city. Why had the press done this? It was nothing new.

******

The modern Western media image of Haiti can be traced to the 1886 best seller, Hayti or the Black Republic. In the book, the British consul to Haiti, Sir Spencer St John, introduced the West to Congo Stew, a Haitian dish of Congo beans and human flesh. Other popular non-fiction titles following. Where Black Rules White, Cannibal Cousins, Black Baghdad. In 1920 National Geographic summed up the media image when they published the following,

“Here, in the elemental wildernesses, the natives rapidly forgot their thin veneer of Christian civilization and reverted to utter, unthinking animalism, swayed only by fear of local bandit chiefs and the black magic of voodoo witch doctors.” (Anon. 1920:497; taken from Lawless 1986).

In 1929, William Seabrook, an American journalist and travel writer for the New York Times would set the tone for the rest of the century when he wroteThe Magic Island, another best-seller passed off as non-fiction in which Haiti was presented as the land of the macabre, mad, and malevolent. In it Seabrook re-affirmed the voodoo-cannibalism link and introduced the West to the Haitian zombie. The zombie, Seabrook taught us, was the “living dead,” the shell of a human who has been killed, risen from the dead and turned into an imbecile slave through some type of sorcery. It’s a ghoul that has haunted the international image of Haiti ever since.

Modern science didn’t help. In the 1980s, after five more decades of increasingly ridiculous Zombie horror films, Harvard ethnobotanist. Wade Davis announced that he had discovered the pharmacological ingredients Haitian sorcerers use to zombify. Both Hollywood and the press would come to adore him for it. His first non-fiction book, entitled The Serpent and the Rainbow (1985), became an international best-seller. The director of Nightmare on Elm Street and Freddy Krueger subsequently made it a major motion picture. Davis second book, Passage of Darkness: The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombie (1988), was an attempt at convincing the academic world that he was not kidding. The preface was written by Harvard Professor and acclaimed father of Ethnobotany, Richard Evans Schultes, Davis’ mentor.

Davis and Schultes’ arguments were fascinating. All the research was there. References were in the right place. It’s clear that both student and professor had completely convinced themselves that they had indeed discovered the secret to the undead. But under scrutiny Davis’ conclusions had about as much substance as claims of Big Foot in Alaska or Vampires in Transyvania. As author Reynold Ducasse points out the two documented living zombies were hardly documented and more likely part of scams where the subjects faked death to avoid debts and responsibility; Davis’s research was orchestrated by non other than Max Beauvoir, Haiti’s premier “Witch doctor” who went to Harvard who had initiated the entire zombi-scientific proof endeavor in an admitted attempt to lend credibility to Haitian sorcery (and it paid off handsomely for Max); it wasn’t until after several false starts and after Davis explained exactly what kind of powder he was looking for that he got.it; and on top of all of this the non-Creole speaking Davis literally wandered around with a wad of cash and paid people who could meet his demands. His principal source for the zombi powder (provided through Max) took months to figure it out just what he was supposed to be giving him, during which time Davis admittingly paid him handsomely. Major television networks, magazines and newpapers reprinted the claims anyway (Time Magazine 1983; CDC 1986) and years after the scientific community had roundly rejected Davis’ puffer fish tetrodotoxin as a chemical candidate for inducing zombification, CBS’s Bill Reilly (1991) declared on Inside Edition that, “Incredibly scientists have now proven that zombies do indeed exist.” To this day (2010), ABC’s internet site gets right to the point, “In real life, the zombies come from the Caribbean island of Haiti” and then, without a hint of skepticism, goes on to repeat Davis’ findings.

But it was the 1980s that were arguably the most special time for the press’s mystical relationship with Haiti. While Davis was “proving” that Haitian zombies exist, AIDS was exploding onto the scene. Trying to figure out where AIDS came from, the United State’s Center for Disease Control identified Haitians as a high risk group. It was a historical first. As Haitian physician Guy Durand pointed out, “Never before in modern medicine has a pathological condition been linked to a nationality” (1984:17). But then, we were talking Haiti, land of the voodoo and zombies. And now, in the face of waves of boatpeople from the Magic Island, we had a mysterious syndrome on the mainland, one that was rendering modern medicine helpless as the stricken among us lost our immuno-systemic ability to defend ourselves and dropped dead, all the ingredients for a mystical explanation. And so rather than carefully scrutinizing the implied accusation, the mainstream press once again began rolling in the mud.

The old skeletons were paraded out of the closet: sacrifices, drinking blood, cannibalism, unbridled sex. Some new ones were added: consumption of menstrual blood, hypodermic injections of water with used needles. Paul Farmer in his book AIDS and Accusation (1992), zeroed on two centuries of the cumulative journalistic slander when Rolling Stone article he described the Haiti-AIDS link as like ‘a clue from the grave, as though a zombie, leaving a trail of unwinding gauze bandages and rotting flesh, had come to announce a curse ‘ (quoted by Farmer 1992; 2 Pezullo 2006:109; for a review see Haiti’s Bad Press, 1986, by Robert Lawless; Simons 1983).

The impact was immediate and devastating. Haiti’s already debilitated tourist sector plummeted from 70,000 hotel paying visitors in the winter of 1981-82 to 10,000 the following season. In the end, it was determined that AIDS probably did come from Haiti to the US, but it came from Africa via educated Haitian(s) who were almost certainly getting their paycheck from the UN or another humanitarian aid organization. It had most likely been picked up in Haiti by Western sex tourists who had found in impoverished young Haitian men docile, willing, and inexpensive partners. Few people were listening.

One would think that, with the embarrassment of zombies and aid accusation behind them, and with the obvious damage done to the Haitian economy and the growing cries of indignation rising up from Haitians community abroad– as well as at home–that in the ensuing decades the mainstream press would tread more carefully with respect to the Magic Island. Nothing doing. By the beginning of the millennium the mainstream English-speaking press had found themselves a new ‘zombie’: Slave children.

According to virtually every major media outlet in the United States and Brittan, by the early 1990s Haiti had 300,000 to 400,000 child slaves; 80% of whom were girls between the ages of 4 and 15 years. The “slave children” were “trafficked,” “sold,” and “purchased” as if in some kind of market whereupon they begin to lead “brutal lives.” The only affection the slaves get, according to most press accounts, is sexual abuse for which journalists consistently offer the most extreme and horrible examples, such as a case in Pembroke Pines Florida, where Timerecounted that, “Florida officials… removed a 12-year-old Haitian girl–filthy, unkempt and in acute abdominal pain from repeated rape.”And, of course, the slaves only get rescued by orphanages, foundations, or UNICEF employees—something I’ll return to in a later chapter. Headlines tell the whole story,

“Of Haitian Bondage,” TIME (2001)

“Haiti’s Dark Secret” NPR (2004)

“The Plight of Haiti’s Child Slaves” Telegraph (2007).

“The Brutal Life of Haiti’s Child Slaves” BBC (2009)

The big point of all this, what most needs to be understood, is the absurdity of it. If the journalists are to be believed, then at 250,000 to 300,000 girls, 25% of Haiti’s female youth was, and still is, enslaved. That makes Haiti the greatest slave state since the Ante Bellum South, an ironic accolade for the first free black republic on earth, descendants of the only successful slave revolt in 1,000 years (there was s large and successful revolt of African Slaves in 9th century Iraq). But similar to the issues of voodoo and AIDS and more recently the irresponsible presentation of post-earthquake Haitian streets as Armageddon, the cry ‘child slavery’ is founded on sensationalist claims, extreme cases, and reporting meant to inflame the imagination and increase readership. In other words, it’s bullshit.

I am not saying that abuse of child domestic servants doesn’t exist in Haiti. It does. It is the Haitian version of what in the United States psychologists call the “Cinderella Effect,” a phenomenon that among other horrifying tidbits includes the statistically valid finding that U.S., British, and Australian children living with one step parent are 120 times more likely to be beaten to death, 15 times more likely to die in a fatal accident, 24 times more likely to drown. These are grim facts of life, as disturbing in the United States and Britain as they would be anywhere else in the world. But whoa to the AP journalist who should depict the Cinderella Effect as a Western tradition, or as institutionalized sadism. In the land of the zombie, who’s to object.

Yet, as with zombies and cannibalism, the press has access to sobering data that contradicts the child slavery claims. The largest and most professional research study of child domestic servitude ever conducted in Haiti was carried out by the world’s foremost research institution on child labor practice, a research group called FAFO (2002), The study was sponsored by UNICEF, ILO, Save the Children, and the Haitian government. What Fafo found is that,

- the number of restavek in Haiti is about 173,000 children–half of the unsubstantiated claims that journalists cite,

- 59% percent are girls—21% less than the unsubstantiated proportion that journalists cite,

- at least 60 percent are enrolled in school– most journalists insist that none are, and

- they are not slaves; no evidence for a market or even trafficking networks exist; most have not been sold but are seeking better living conditions or are rural children doing domestic chores in exchange for room and board and the opportunity to go to school in a town or the city—suggesting thatmany of the supposed slave children are no more enslaved than middle class Americans performing chores at boarding school.

Congruently Fafo also found that,

- host parents tend to beat their own children more than often than they beat the “slaves,”

- the “slaves” had equal or greater sleeping time, and

- more often than the natural children of the home the “slaves” had a bed, mattress, or mat

(Fafo 2002: 56–58; Fafo credentials and the study are published online where anyone can read them (http://www.fafo.no).

But none of this got in the way of mainstream journalists. Only one, out of the 18 articles and documentary television shows I reviewed even mentioned the study. That was Jontahn Katz of the AP (2010)—he wrote the article after I told him about the Fafo study– and he subsequently, and without explaining why, ignored the results, opting instead for the image of beaten and sexually abused child slaves.

It is unfair perhaps to put this all on the journalists. The driving force is the editors back home and, as I will show in a later chapter, the charities collecting money supposedly intended to rescue slave children. But just to get the record straight, the fact is that what the journalists were looking at is poverty, not slavery. Haiti is poor. Children work. In fact, not unlike families on the 18th century American frontier, one of the reasons people in Haiti have many children is because they have to do a great deal of work to survive (I wrote a book about this: Schwartz 2009). All poor Haitian children fetch water, empty chamber pots, wash dishes, sweep and mop. And with all due respect to the journalists such as CNN ‘s Sanjay Gupta (2009)—our hero from the hospital—when they report back from Haiti that, ‘on a Sunday at 5 a.m….what I saw next was hard to imagine’ and then, like a scene from body snatchers, tells us that, ‘Hundreds of kids, ranging in age from 4 to teenagers, were making their way down the surrounding hills that were covered in small huts. They all carried a bucket…’ they have no idea that what they are looking at. They are looking, not at hordes of child slaves, but hordes of children, of all ilk, doing their morning chores.

But instead of responsibly trying to figure out and verify who the children are, they do what they have always done to Haiti. They adhere to ‘hearing is believing,’ and accept preposterous but dramatic explanations sure to mesmerize American viewing audiences. They say things like, “most of these Restavek carried the water up small mountains, more than a 1000 feet in the sky” (Sanjay again–which sounds great but is emphatically not true; while only about 40% of homes have piped water, nowhere in Port-au-Prince does anyone have to walk up a 1,000 foot high hill to get it).

Again, in a later chapter I try explain why, in concert with NGOs, otherwise responsible journalists radically misrepresent Haitian patterns of behavior and how they get away with it. But for purposes here let me finish with the press because I am not done. In the midst of all the fervor about child slavery, came the gangs, kidnappings, rapes, and mud cookies

In the 1990s, the Haitian population became the very last country in the Caribbean Basin to get sucked into drug transshipment and the concomitant emergence of the youth gang phenomenon and crack cocaine use. Indeed, by urban Latin American standards the vast majority of Haitian youth remain, even today, sexually and socially conservative. Far more so than their US counterparts or, with the exception of Cuba, those of neighboring islands or the Dominican Republic (the country that shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti). But by the early 2000s the country was being portrayed in the press as rife with gangs. Neighborhoods such as Cite Soley were declared the most dangerous on earth. Once again, the headlines say it all,

“Haiti Gangs” ABC March 14 2006

“U.N. Troops Fight Haiti Gangs One Street at a Time” NYT February 10, 2007

“’Misery Breeds Violence’ In Haiti’s Seaside Slum” CNN May 15, 2009

Perhaps most spectacular of all, otherwise responsible journalists were sending back un-confirmed reports of male and lesbian street gangs dedicated to raping young women.

”In Haiti’s chaos, unpunished rape was norm”Miami Herald, Sun, May 16, 2004

“The Rape Epidemic” New York Times, December 2, 2007

“Rule of the rapists in Haiti” The Sunday Times, May 6 2008

“Haiti Kidnap Wave Accompanied By Epidemic Of Rape” Reuters , 8 Mar 2007

This was good press, or at least the kind that sells. Never mind that most of the journalists had never actually seen or talked to a gang member, especially those dedicated exclusively to rape.

And never mind that for much of this period Haiti was in the throes of a civil war between the armed representatives of the 90% plus population that had supported a democratically elected president and the 10% of the elite class that had backed a rebel movement that overthrew him. Never mind that many people in impoverished neighborhoods saw them not as gang leaders but rebels in this war, that there source of arms and money was political groups and never mind that while extremists in Iraq, Pakistan, and Afghanistan were executing dozens of people at a time, strapping bombs to their bodies and killing in a single incident more than Haitian “radicals” on both sides of the conflict killed in any given three month period; or that while, yes, rapes occur in Haiti, but if we take figures put forth by victim advocate groups (official figures don’t exist) then the level of rape is a fraction of the US rate in a typical year—a point I return to in chapter ##. Never mind all that. Journalists referred to paramilitary groups such as the “cannibal army” without ever explaining that they were not cannibals. They described Port-au-Prince as “the most dangerous city on earth” without ever acknowledging that statistics suggested that it might be safer than most US cities. And they wrote of gangs of rapists, including men with the foreskin of their penis’s slit open and stuffed full of ball bearings–so they could damage women—without ever acknowledging how preposterous the notion is (infection to begin with; then perhaps the challenge of getting a good hard-on when you are shackled with ring of heavy steel marbles; to say nothing about what those marbles must do to inhibit sensitivity and orgasm).

There were no stories marveling over how, in the middle of a class war, people could walk unguarded and with impunity in 99.99 % of the country. There was no echo through the news media when the head of the UN announced that despite 1,356 registered kidnappings in 2006– one of the worst years of violence and the hottest part of the civil war–Haiti had the lowest homicide rate in the Caribbean: one fifth the Caribbean average, one sixth that of the neighboring Dominican Republic, one ninth that of Jamaica, one third that of Puerto Rico. Moreover the homicide rates for the past six years do not separate out political violence. This means that Haitians have arguably conducted the most benign civil war in the history of the world. Throughout the entire period, 2004 to 2009, the official estimate of homicides is 1,600; that’s 1/10th the homicide rate for the U.S. capital, Washington D.C., 1/10th that of Haiti’s neighbor (the democratic and politically stable Dominican Republic, a country of approximately equivalent population size but twice the land mass and about 20 times the GDP: $405 vs $8,500). Even if you take the most controversial claim of 8,000 homicides for the period 2004 to 2009, it is still only ½ of the Washington D.C. and Dominican homicide rates (ACR 2009).

Apparently, that’s not news.

Mud Cookies

And as if all that is not enough, amidst all this rape, kidnapping, and murder came mud cookies.

In 2008, Associated Press journalist Jonathan Katz—the same journalist who ignored the Fafo data that would have had a sobering effect on the child slavery hoopla— reported people eating dirt as “regular meals” sometimes, he reported an informant telling him, “three times per day.” Nevermind that’s not possible, no one can survive on dirt. Or that Haiti has an old and fascinating industry of geophagy, certain areas of the country specializing in processing clays and limes that contain essential minerals and that people consume it out of habit, like snuff, or to tighten stools when sick, like Imodium. And never mind that Katz himself, by all accounts including my own one of the best journalists working in Haiti and fully aware of the customs and never intending to say that people were surviving on dirt. Never mind all that; people so hungry that they eat dirt is news. With the proper editing and fact checking the report went out on the wire and rocketed from one major English newspaper to another.

Haiti’s Poor Resort To Eating Dirt Cookies, The New York Sun January 30, 2008

Haiti: Mud cakes become staple diet as cost of food soars beyond a family’s reach, The Guardian, July 29, 2008

Dirt Poor Haitians Eat Mud Cookies to Survive, Huffington Post February 19th 2009

Even National Geographic latched on to dirt eating,

“Poor Haitians Resort to Eating Dirt” National Geographic News, January 30, 2008

And then came the Earthquake.

*****

When it was all said and done, in the anarchic hell that was ‘reportedly’ port-earthquake Port-au-Prince, with 1.5 million people homeless, at least 217,000 dead, 4,000 of the country’s most dangerous prisoners escaped, 80% of buildings destroyed, hunger and hopelessness, looting–the violence for the week following the earthquake was spectacularly low. The official tally:

- two Dominicans wounded—clearly intentional (what we don’t know is if they were trying to sell aid, as some Dominican truck drivers were doing)

- one girl killed by a police man’s falling bullet—apparently an accident

- two men that the police allegedly bound and executed—foreign journalists reported them as ‘looters’ (but since in most cases the police were permitting looting we can assume there is more to the story)

- a looter shot by a security guard—intentional (but we don’t know what happened prior to the shooting, if the man had threatened the guard, if he had returned several times, if there had been some kind of fight)

- one cop shot by his partner—another accident (we think)

- at least two people beaten to death by vigilantes (in anarchic Haiti, vigilante justice is common, arguably one reason that crime isn’t as high as other areas, there are no police to protect the criminals from the population).

That in a metropolitan area of 3 million people and in the wake of the worst disaster in the history of the Western hemisphere. In other words, there was considerably less than the average 55 people killed every week next door in the Dominican Republic; about the same as a rough week in Washington D.C., which has one sixth the population of the earthquake zone; and only a fraction of what occurs in even a single 24 hour period in Honduras, a country of 3 million less people than Haiti but where an average of 15 people are murdered daily. And in the six months following the earthquake, the rape epidemic reported in the press, the figure was, using the statistics from rape advocacy groups that include even attempted rape, about 21 in 10,000, that’s 8 points less than the US rape rate of 29 for 2010.

No newspaper or television journalists reported that.

*****

It’s not at all clear who went first the press or the military, but on the 19th of January there was an abrupt change in reporting from both. Indeed, an about-face.

General Keene, who only two days before had been getting ready to send the troops into action, was suddenly acting like he had never been worried about anything, “The level of violence that we see right now is below the pre-earthquake levels.” (January 18, 2010 US Southern Command Transcriptshttp://www.southcom.mil/AppsSC/news.php?storyId=2058

On a flight to India, Defense Secretary Robert Gates repeated the point when he told reporters, “There has been a lot less violence in Port-au-Prince than there was before the earthquake.” (CNN 20th , in the Med PiH lopital file)..

The UN, who had spent much of the week hermeutically sealed in compounds, only venturing into the streets in tanks or armed details and insisting that no one else go out without an armed security detail, suddenly changed their tune as well. Acting as if they too had never been worried about anything in the first place, UN spokesman John Holmes told the press, “It’s very easy to convey the impression by focusing on a particular incident that there’s a major security law and order problem arising. But in our view, that is not the case.” (ABC 19th).

It’s not clear what happened. Perhaps it was because public radio and satellite stations began running independent broadcasts that contradicted the mainstream press and the military, indeed blaming them for fear-mongering and for slowing the aid process. That same day, Evan Lyon of Partners in Health told PBS,

We’ve been circulating on the roads to 1:00 and 2:00 in the morning, moving patients, moving supplies, trying to get our work done. There is no security. The UN is not out. The US is not out. The Haitian police are not able to be out. But there’s also no insecurity… It’s a peaceful place. There is no war. There is no crisis except the suffering that’s ongoing. . . . listeners need to understand is that there is no insecurity here. There has not been, and I expect there will not be.

Perhaps covering their respective asses, the big media outlets, as if they had never thought different, fell right in line.

Haiti’s streets ‘safer than before earthquake’ (ABC, January 19th )

Karl Penhaul of CNN, which had been broadcasting mayhem and hell for a week, reported that,

“Over the last two or three days we have seen instances of looting, but we can’t over-exaggerate that point. These are isolated incidents of looting in the commercial districts, where people are gaining access to warehouses that were largely destroyed anyway by the earthquake.. . ”

So on the 17th the military was planning to move in and pacify the violence and mayhem that had engulfed Haiti. On 18th it the situation had worsened, all hell was breaking loose, Marshall was law imminent. But on the 19th the marauding Haitians seemed to melt away and suddenly insecurity in post-earthquake Port-au-Prince had never been an issue at all.

I can’t explain it. All I can do is summarize what happened. And based on all the reporting there should have been some profuse apologizing on the part of the press for it was arguably them who caused the fear. It was arguably press reporting that caused rescue workers to congregate in the same safe and guarded compounds and that had sent some, like the Belgian Medical team that Sanjay Gupta was with or the Fairfax crew that Ben and I accompanied, fleeing from sites where people desperately needed them. Whatever the case, for many it was too late.

*****

The fear would linger. The 20,000 troops and the thousands of aid workers who had come to provide emergency relief where now effectively under security restrictions. The UN had carved the city into colored zones. In red zones aid workers could not enter at all. In orange zones they had to have their windows rolled up and they could not get out of the vehicle. In yellow zones they could enter but only at certain times of the day. The least secure zones were, of course, the poorest. And the green zones, those that were safe, were the wealthy areas where little to no aid was needed at all.

Aid would subsequently be delivered in tightly controlled “sites” drawing crowds that sometimes reached into the tens of thousands. There was massive frustration and resentment. Fights would break out. Young men would take huge shares. The old, infirm, women and children would get nothing. The people came to refer to getting aid nan batay “in a battle.” In many areas they didn’t have to even go to receive aid to suffer the consequences. Resentment among those who did not get food gave way to raids and attempts to drive others off. As I recount in a later chapter, my own assistant’s camp was attacked, a group from another camp resentful that they had not received food and blaming those in her camp came running wildly through, throwing rocks and slicing the plastic and cloth tent covers.

The press of course took a lot of photos.

But the story was getting old. The initial excitement had worn off. It was becoming clear that Haiti was not descending into a massive gang fight. That’s not news.

******

In summary, the mainstream press did what it always does to Haiti: In the name of selling newspapers and increasing television viewer audience it re-affirmed the image of Haiti as the land of the macarbe, the mad, and the malevolent. In their most dishonerable moment, their opportunity to help, to quell the fear and smooth the way for rescuers and medical workers and the deliverers of aid, a moment when newspaper editors could have stepped in and made sure that responsible reporting ruled, the press failed. Indeed, they did worse. Television producers unleashed what the Huffington Post called, “the biggest international deployment of TV news talent since the 2004 tsunami.” But the press, rather than telling us what was happening and responsibly reporting on the needs and the degree of safety, tried, in the name of readers and viewership, to entertain and scare the hell out of us and, in the process, they set the ground work for a second disaster, the rescue disaster.

As with the rescuers, if they publicly admitted what they did, so that we could try to prevent the same from happening again –and they indeed realized what they were doing as demonstrated with the abrupt turn around—then I would not feel that I have to write this chapter. But instead they sounded an alarm of panic, never admitted their mistake, and when it was over people like Anderson Cooper proudly accepted a medal on the lawn of the destroyed Haitian National Palace. Others would be nominated for Pulitzer Prizes and photo awards.

Why had the press done this? Why does the press always do this?

******

Maybe this sounds like a cliché, but it’s three weeks after the earthquake, I am riding my motorcycle around the former St Pierre Park in the upscale Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Petion Ville. Behind me, on the back of the bike is a reporter friend of mine. He’s a cool guy, seasoned investigative reporter who’s seen Iraq and Afghanistan. We are passing the park. While before it was green space, park benches and trees, now it is a tent city, a mass of blue and dingy white canvas covers the entire park. Tiny paths wind through the shelters. A line of latrines border the street and the odor of urine and feces fills the air. We pass the police station, a monolithic dingy white and blue building that matches the tent city. A man with an Uzi stands guard in front of an SUV. Next we are passing the Mayor’s office. “Look!” I say to my friend, “there’s a food distribution.”

I stop the motorcycle.

A long line snakes around from the back of the building and through the front gate. The distribution is quiet, orderly. People stand patiently in their places. ”Man that’s fantastic,” I am saying, “Let’s put that in the paper.”

“Look man,” my friend says, frustrated, “You have to understand.” He’s adjusting the strap of his book bag and then shifting the notebook under his arm, “If the plane doesn’t crash, it’s not news.”

Title of article in The Daily Mail, United Kingdom’s second biggest-selling newspaper

As an anthropologist I can’t help but note and be fascinated by the similarities to witchcraft accusation. Albeit in a modern, sophisticated academic guise, developed world experts were implying that Haiti, through use of sorcery and witchcraft, had given way to the spread of a horrific disease.

And I am not saying that there were not men wondering around with bandanas wrapped around their faces and machetes in hand. And yes, it looked bad. There had been an earthquake. Thousands of buildings and businesses destroyed, tens of thousands of people killed, and in the midst of all this the doors of the country’s main penitentiary—located right in the middle of Port-au-Prince—had been unlocked and Haiti’s most dangerous convicts and gang leaders had escaped into the general population. And yes, at night shots were ringing out throughout the city.

The next day, to their credit, 60 minutes played it safe and focused on the number of dead piling up at the morgue and the medical emergency crisis that confronted Haiti. For better or worse, they said nothing about the violence.

“Violence descends on shattered Haiti.” (ABC News, January 17)

“Quake desperation: Witnesses are reporting chaos as authorities fail to take control of the streets” (Reuters January 17)

It was by no means everyone who wrote bad. Leger 1907 rebuffed it. And there were Individuals such as US ambassador E.D. Bassett….

‘I went out among the country people. I spoke their language (French Creole) and I personally knew hundreds of them…the cannibalistic practices described have no existence whatsoever in Haiti… If they did exist it would be most extraordinary–I repeat it, most extraordinary.’ (New York Sun 1901; quoted in Leger 1907:248)