In the wake of the January 12, 2010 Haiti earthquake, the world witnessed the growth of what would become the largest refugee crisis on the planet. If we can believe claims from the United Nations, the US and the EU governments, and the humanitarian aid agencies that together received some $3 billion in donations from individual and corporate donors, the displaced population in Port-au-Prince reached 2.3 million people, 1.5 million of whom were in living in temporary camps located in the vicinity of metropolitan Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti. That was six times the next largest complex of refugee camps in the world at the time, the 239,500 people in Dadaab complex of refugee camps in Kenya who had fled civil war in Somalia. But in the case of Haiti, people were not fleeing violence, they were supposedly displaced by the earthquake. Supposedly. The fact is that those organizations giving us the data could not be believed. As seen here in this chapter from the book The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle, the crisis was largely the creation of those very organizations collecting the money on behalf of the “earthquake survivors.” Specifically, the Haiti earthquake refugees crisis was the result of three forces:

- First and foremost, the radical exaggerations and hype from United Nations, representatives of the US and EU and NGOs bent on collecting as much donated money as they possible could.

- Attempts on the part of impoverished Haitians to partake in the donations; aid they knew very well had given in their names as they had access to reports on the radio and to information from family in the US, Canada and elsewhere.

- The attempts by many of those impoverished Haitians to use the earthquake crisis as an opportunity to appropriate land legally in position of elites, a process that has been common for the two centuries of Haitian History but the opportunity for which has been intensified with the post-earthquake aid tsunami and presence of international aid agencies.

The Story of the Haiti Earthquake Camps

Being an Earthquake “Viktim”

“When they see us coming they run out with their sheets and they throw up a tent.” It’s July 9, seven months after the earthquake and I am talking to Maria who is working in the camps. Maria is middle class, fiftyish, from Honduras. I haven’t asked her for this information, she’s volunteering it. We are in a restaurant having dinner. My Foreign Service friend, Joseph, is with us, as well as another aid worker, a woman from Rwanda. I asked Maria about her job and she started telling me about the camps. “Many of these people, they have homes,” she says with a tone of exasperation. “In some areas we work they were not even effected by the earthquake.” World Vision, her employer, has assumed responsibility for 15 camps. She describes what happens after the aid workers arrive,[1]

“When we take over a camp or move people to places like we did on the border, every week there are 100 more people. They have their bed sheets over their rickety little wooden frames… No one is living there. But when they see a World Vision vehicle, they come running.”

Maria is not telling me anything I don’t already know. But what is surprising to me is that it’s so obvious even to her. She speaks no Kreyol and no French. She has no special insight that would help her see or understand anything about Haiti that anyone else cannot see and understand. She has not been out living in camps or doing hard core research to get this information. She just visits camps as part of her job. Yet, that very day Nigel Fisher, UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Haiti, had declared in the United Nations official ‘6-Months After Report’, “a staggering 2.3 million internally displaced persons,” of which 1.5 million were living in camps. That would have been 46 percent of all 3.375 million people in the entire strike zone; 58 percent of those living in urban areas. But Fisher didn’t say anything about the fake tents. Maria doesn’t understand why. “It is,” she’s telling us, “obvious.” And it bothers her. “It is like no one cares whether the recipients need aid or not.”

Lest Maria and I be misunderstood, let me step back for a moment and explain something. Maria was not talking about the tents and makeshift shelters where people moved all the possessions they could scavenge from their collapsed home. There were many of those shelters. Tens of thousands. Maria was describing another kind of shelter and camp; the kind that, if any aid worker or journalist had done the math or a survey—and I’m getting ready to recount that we did both—they would have known there were even more of. And they would have known that most were bogus. These shelters had no clothes hanging to dry on a line, no charcoal fires, no pots and pans, no people sleeping in them. If you poked your head inside one of them, you would more than likely have found them empty and you would often have found a surface on which no one possibly could or would sleep: rocks on the floor, tree roots sticking up.

These were what my Foreign Service pal Joseph called “aid bait.” They sprang up throughout Port-au-Prince and in a 40-mile radius around the metropolitan area and even in some towns and cities as far as 100 miles away from the earthquake strike zone. Haitian Vilmond Joegodson, who grew up in Cité Soleil, one of Port-au-Prince’s poorest neighborhoods, and who moved into several of the camps, described the process:

All that was needed was eight long sturdy branches and some sheets to hang from them to represent walls… The NGOs decided to visit them and to distribute whatever tents or tarps they still had. To qualify for those donations, or other aid, Haitians needed to have a place etched out in one of the camps and to have demonstrated some proof of residence.

Everyone kept their ears open to find out where the NGOs were distributing the tents most generously. The objective was to go to that camp and demonstrate a presence. Then wait. Sometimes people squatted in a number of camps at the same time in order to cover all their bases.[2] Joegodson 2015

Absurdity of the Numbers

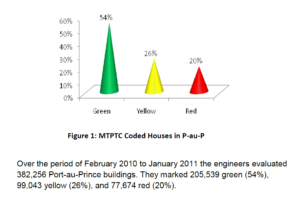

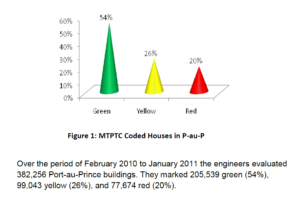

You did not have to take my or Maria or even Joegodson’s word for the fact that many of those people in the camps were not really “viktim” of the earthquake. By the time that Nigel Fisher was declaring 1.5 million people in 1,555 camps, it was already reasonably certain that it was not 70 percent of the buildings in Port-au-Prince that had collapsed. It was 7 percent of the buildings. Another 13 percent were damaged such that demolition of the structure was recommended. That meant that a total of 20 percent of the buildings were unfit for habitation. And that meant that no more than 29 percent of the population should have been what the authorities were calling IDPs (internally displaced persons); at least, not if the criteria for being an IDP was that the home you were living in was destroyed. If we extend the definition of an unfit home to include the yellow houses—the 26 percent of houses that were damaged but still reparable—there could logically have been no more than 46 percent of the population homeless, which is closer to the 68 percent of the population the UN reported as IDPs. The remainder of the houses were “green” which meant that they had no significant structural damage. But there were still big problems with the calculations. [3]

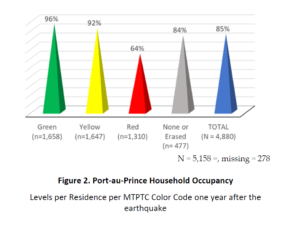

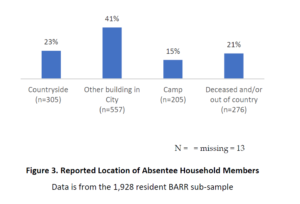

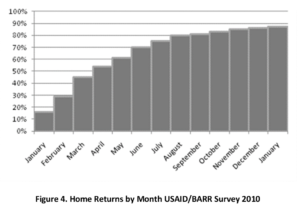

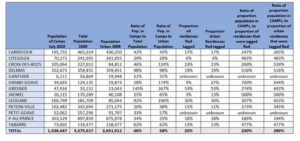

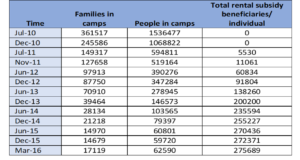

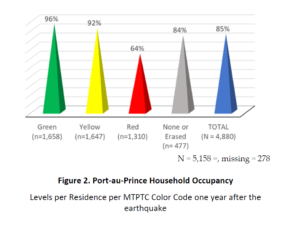

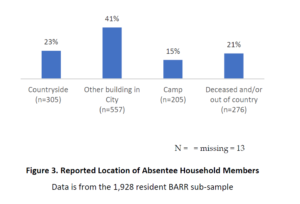

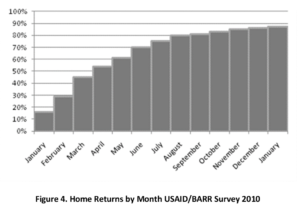

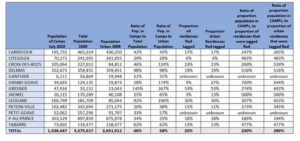

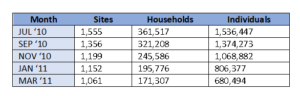

For those of us who lived in Port-au-Prince, we knew that most homes were abandoned after the earthquake had been reoccupied within a couple of months of the diaster. And once again, you didn’t have to take our word for it. In the BARR Survey we found that at the height of the exodus exactly 68 percent of residents in the earthquake impacted region left their home. That extrapolates to 2,040,000 people. But not all of those people went to camps. The UN estimated that 24 percent of the IDP population had gone to the countryside or were living in the homes of family or friends. BARR, UN’s OCHA, and the University of Columbia working with Sweden’s Karolinska Institute all found similar figures. Others were living in the street in front of their home. In short, less than half of the IDPs went to camps; or more precisely, 900,000 people or 30 percent of the total population in the earthquake strike area went to the camps. But they began returning home within weeks of the earthquake. BARR tells us that 70 percent of people who had left their homes had returned to them by July 2010, when IOM—that organization that the UN had designated as responsible for coordinating aid to camps in Haiti—was estimating there were 1.5 million people in the camps. At the one-year anniversary of the earthquake, when IOM estimated there were still 1 million people in camps, BARR tells us that 85 percent of those people who had left their homes were back in them. Even the 78,000 red-tagged-structure residences—those recommended for demolition—had a re-occupancy rate of 64 percent. For the 100,000 yellow-tagged residences—those damaged but reparable—the reoccupation rate was 92 percent; and for the 206,000 green-tagged structures—those that were undamaged—the re-occupancy rate was 96 percent (see Figure 2, below, and Figure 3, next page). Even if we were to include all the missing variables from the survey for reasons of non-reporting, we had solid data that at least 80 percent of people had re-occupied their homes one year after the earthquake. So once again, even if we’re liberal about the estimate, at the one-year earthquake anniversary no more than 20 percent of the population—about 675,000 people—should have been IDPs. That’s not people in the camps; that’s IDPs, meaning people who had not returned home. Based on reports in the BARR survey, of the 1,356 residences with absentee members, only 15% of those absentees were still located in camps (see Figure 3, below). This meant that of people from the earthquake impacted area, no more than 101,250, people who had been living in Port-au-Prince at the time of the earthquake were living in a camps. Yet, the camp counts from the government and OIM found—or claimed–that there were still 1 million people in camps. Some of these extra people people could and certainly where from outside the earthquake strike area living in camps, but the point is that something was definitively out of whack with reality. In some Port-au-Prince area counties, there were more people claiming to live in camps than the total number of people living in the county when the earthquake hit. [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

Even without the Numbers, They Knew

So those are the numbers. But the fact is that you didn’t even need the numbers. Everyone in any position of authority knew damn well that many people in the camps were only pretending to be IDPs. One of the first things USAID/OFDA representatives told me about when they briefed me for the BARR Survey was the massive opportunism. The two women who briefed me, one from OFDA and one a consultant for the U.S. State Department, told me point blank, “We know that a lot of the tents are empty.” They explained that SOUTHCOM (U.S. Southern Command) had been into the camps at night with infrared goggles and many of the tents were empty. “And,” the woman working with OFDA added, “we know that people in the camps are splitting families to occupy multiple tents so that they can get more aid.” So when UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Haiti, Nigel Fisher, announced to the world that there were 1.5 million people living in camps, there is simply no way that he himself could have believed the figure was remotely accurate. Once again the leaders of the humanitarian aid effort were flat out lying to us. [10]

Table 1: Populations of Camps vs. Communes/Counties

So Why the Lies?

What we were seeing with the growing camps was in part a scramble to get aid that the humanitarian organizations were giving away. But what the humanitarian aid professionals and the press seemed to miss was that for the poorest people it was more about escaping rent payments and gaining access to free land, i.e., land invasion. Just like the poor and middle class throughout the world, urban rents are a huge burden for those who have to pay them. The first goal of most independent household heads is to own their own home, and the earthquake presented a golden opportunity to get one. I’ll get to that in just a moment. It’s interesting and useful because it helps us make sense of Haiti and the impact of humanitarian aid. But just as interesting, for me, and in the context of this book, was the exaggeration, indeed, outright lying from the humanitarian sector. For despite the obvious mathematical distortions, despite the fact that even common aid workers like Maria were aghast at the scale of the opportunism, despite that behind closed doors we all went on at length about the rampant opportunism, the leaders of the Humanitarian aid community, like UN director Nigel Fisher, kept a straight face while bewailing to the press and overseas public absurd numbers of homeless. In that respect it was very much like the orphans and rapes. And just as with the orphans and rapes, lurking behind it all was pursuit of money from sympathetic overseas donors.

The Money

The NGOs were pouring aid into the camps. Or at least they appeared to be. Olga Benoit, the director of SOFA, the largest women’s organization in Haiti—seen in chapter 8 on the rape epidemic—recounted that, “it was like an invasion of NGOs. They went to the camps directly. This camp was for CRS, this camp for World Vision, this camp for Concern.”

Some might think that’s alright. Why not? Even if many people in the camps were not direct victims of the earthquake, they must have been in need. Yolette Jeanty of Kay Fanm, the second major feminist organization in Haiti tells us why that really wasn’t alright:

The great majority of ‘sinistre’ (desperate people) were and still are inside the neighborhoods. Those people didn’t want to go to the camps, they stayed home. Even those in the camps, many don’t sleep there. They go home to sleep. They only come to the camps during the day to get water or whatever they might be giving away. But the NGOs, they all go to the camps.

By ignoring the neighborhoods, the humanitarian aid workers were able to avoid that major impediment we saw in early chapters of this book: security. In the weeks after the earthquake, the press had not only sold a lot of newspapers with sensational stories of gangs and street battles, they had also frightened the hell out of everyone, not least of all the humanitarian professionals working for NGOs and UN agencies. In 2013, criminologist Arnaud Dandoy wrote about the absurdity of what he calls “moral panic” among the humanitarian community in Haiti. The typical NGO headquarters in Port-au-Prince was secured behind ten foot walls topped with concertina wire. Its employees were restricted by curfews, forbidden to even roll their windows down in certain neighborhoods or enter others, precisely those neighborhoods most in need of humanitarian aid. The camps solved a lot of problems. Despite the fact that the NGOs and the grassroots organizations such as KOFAVIV were reporting skyrocketing violence, the camps could be patrolled. UN soldiers were stationed at camps where NGOs worked. Security experts could monitor the situation. And at night, when things supposedly got really bad, the aid workers weren’t there. They went back to the elite districts, to their apartments and hotel rooms located, once again, behind high walls and in guarded compounds.[11]

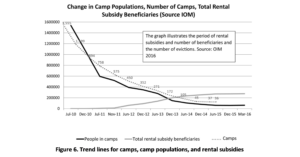

The problem with focusing on the camps, from a humanitarian perspective, is that they were missing a lot of the real victims. But what’s worse, from the perspective of helping, is that it was precisely the indiscriminate giving, the protection of the camps, and the carte-blanch certification of camp residents as legitimate that encouraged opportunists to pour into the camps. The camps grew for seven months after the earthquake, long after the last aftershock. They went from 370,000 people living “under improvised shelters” on January 20th (IOM), to 700,000 on January 31st (USAID 2010), to 1.3 million on March 1st (UN 2010), to Nigel Fisher’s claim of 1.536 million in 1,555 camps on July 9th. Among those numbers were a lot of opportunists who sought to benefit from the aid, many of whom already had little grey concrete homes near the camps, homes that had not fallen down. And most of whom had some means of earning a living, however meager. And it’s unfair to those in need that such people would pretend to be victims left homeless by the earthquake. But more to the point here, it’s hard to overlook the fact that those who most benefited from the lies and from permitting opportunists to indiscriminately pour into the camps were not the impoverished opportunists feigning to be homeless. Those who most benefited from the lies were the foreign humanitarian aid agencies and their workers, many of whom were living in $50,000 per year hotel rooms and apartments. And it’s here where we can best understand why the United Nations and the NGOs were spewing untruths and omitting facts about the camps. [12]

The camps brought in donations. Whether deliberately or by default, the humanitarian aid organizations used the camps in much the same way as the people pretending to live in them: as aid bait to get overseas donors to give. The NGOs and UN agencies presented the camps to the overseas donors as a humanitarian aid smorgasbord of ills. Hundreds of thousands of vulnerable people in central locations with every imaginable need: food, water, shelter, security, lighting, sanitation, health, therapy. They were getting paid to take care of those ills. And by making a show of their efforts, taking lots of photo opportunities, it was as an easy solution to make it look like they were doing something. They didn’t have to go to the neighborhoods. Didn’t have to implement rigorous mechanisms for vetting real victims from the pretenders. In this way the aid agencies essentially conspired with those pretending to live in the camps by not telling the truth about them and by wanton distribution of the aid. What makes it sad and distressing, if not criminal, is that those most in need, the weakest and most vulnerable who had gone to camps were, by and large, not getting aid. In the six years since the earthquake, I’ve listened to it over and over in focus groups:

The camp committee took everything that was given for the camp. They took the tarpaulins and if you needed one you had to buy it from them for 250 or 300 gourdes. If not, you lived in the rain. Sometimes we saw trucks come with food. But they took everything to store at their houses. They didn’t give us anything. Some of these people had houses in good condition. The camps offered them more advantages than staying in their own houses.

Erns Maire Claire (Female; 43 years; 3 children; teacher):

Focus Group for CCCM OCHA Cluster, March 12, 2016

What I saw happening was that they sold the food. Sometimes they made arrangements with other people and gave them food several times. These people sold the food and shared the money with them.

Focus Group for CCCM OCHA Cluster, March 13, 2016

Cadio Jean; Male; 43 years old; 4 children; mason/ironworker)

So there was waste and the NGOs were doing a lousy job getting the aid to the people who really needed it. There was massive embezzlement and hoarding. But if most of the people in the camps were not really earthquake victims and most were not getting anything from the humanitarian aid agencies, why did several hundred thousand people continue to live in camps for years after the earthquake? The answer is something that everyone seemed to speak about constantly but no one, not even journalists seemed to realize was driving the camps. The answer is because they were renters and they hoped to get a piece of land and a home. Indeed, it was a consummation of Haitian historical trends, the invasion and expropriation of land, and most recently that of the invasion of Haiti by NGOs and the emergence of being a viktim as an opportunity to escape poverty. The poorest people and relative newcomers to the city were mobilizing their status as “earthquake victim” to seize land.

History of Land Invasion

To understand what drove the “real” and the “not-so-real” IDPs to move into camps, or at least act like they had, one has to first understand two things: urbanization and the history of land acquisition in Haiti. Like most developing countries, over the past 65 years Haiti has been the site of massive migration from rural areas to towns and cities. The entire country has gone from 13 percent urban in 1950 to more than 50 percent urban today. While in 1950 Port-au-Prince had a population of less than 150,000 residents, today there are over 2 million. And that’s just within the city’s borders. There are some 3 million in the entire Port-au-Prince metropolitan area. One-third of the population of Haiti. And the driving force behind much of that urbanization and, similarly, what made being a viktim one of the major economic opportunities for the Haitian poor, had a lot to do with U.S. economic policies.

The American Plan

In the 1970s Haiti, like many countries in Central America and the Caribbean, was still largely rural. Its inhabitants were small-scale farmers. It had poor roads, and inadequate communication, educational, and health systems. It was underdeveloped. And that underdevelopment was arguably a more pressing problem in Haiti than in other small countries in the region because, at 168 people per square kilometer in 1970, Haiti had a population density twice that of neighboring Cuba (76 people per square kilometer) and almost twice that of the neighboring Dominican Republic (91 people per square kilometer).[13] Over 95 percent of Haiti was reportedly deforested, causing erosion so severe that reputable scholars were already referring to it as the worst in the world.[14] The erosion wasn’t just a problem for Haiti. The runoff was impregnated with sewage, plastic bags, bottles and petroleum residues. It billowed out from Haitian rivers, forming huge underwater clouds that contributed to the destruction of ecologically sensitive coral reefs throughout the Caribbean. Something had to be done.[15]

The United States was the country that for almost one hundred years had taken upon itself the task of policing Haiti and its neighbors. It had already invaded Cuba four times, the Dominican Republic three, Honduras seven, Nicaragua seven, Panama four, Guatemala and El Salvador once each, and Haiti twice.[16] Moreover, there were new opportunities on the horizon. The promotion of overseas sales of U.S. corn, wheat, cotton, and rice was high on the U.S. congressional agenda. Subsidies for these products was as much as 38 percent in any given year. France and Germany—both of which would join the U.S. in dumping massive amounts of surplus food on the Haitian market– were also aggressive promoters of their own farm products. The EU subsidized its grains at an even greater rate than the United States, 48 percent.[17] There was also the offshore industrial sector, particularly the $100-billion garment industry of which Gildan and Palm Apparel, seen in Chapter 5, would become a part. The U.S. government had begun to cultivate the garment sector in Haiti as far back as 1971 when in exchange for supporting the continuation of the Duvalier dictatorship from father to son, the Haitian government agreed to create an environment hospitable to U.S. investors interested in the offshore assembly sector. Customs taxes were eliminated, a low minimum wage guaranteed, labor unions suppressed, and U.S. companies given the right to repatriate profits. By 1980, there were some two hundred mostly U.S.-owned assembly plants in the country.[18]

It was at this juncture that the U.S. government, working through USAID and the planners at the world’s major international lending institutions—the U.S. and secondarily EU controlled World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—adopted new policies that would, with perhaps the best of intentions, all but destroy the Haitian economy of small farmers. Calling it “economic development,” the growth prospects of the assembly industry meant that migrants to urban areas were economically useful as factory workers, something that justified eliminating farming as an alternative livelihood strategy. The objective conveniently coincided with those of U.S. agricultural interests and the conservationist goal of moving peasants away from destructive hillside cultivation of bean and corn crops that caused so much erosion. The logic seemed overwhelming.

So a plan was hatched. At the time they called it the “American Plan.” For the rural areas, the policy planners envisioned neat rows of high tech agriculture, coffee, mango, and avocado plantations, and modern factory-style poultry barns. For the urban areas they envisioned burgeoning industrial parks where peasants who had been displaced to make way for agro-industries could be transformed into factory workers. The USAID designers described to Congressional oversight committees a new Haiti that would undergo, “an historic change toward deeper market interdependence with the United States,” a relationship that would release the “latent Haitian agro-industrial potential waiting to explode.” The scheme, as USAID Administrator Peter McPherson testified before the U. S. Congress, would ultimately “make the prospects for Haiti as the ‘Taiwan of the Caribbean’ real indeed.”[19]

How to Destroy an Agricultural Economy

It might not have been such a bad idea. Haiti clearly needed help. But it didn’t happen like they said it would. A good example was the Haitian rice industry. Until the 1980s, Haiti was almost entirely self-sufficient in rice consumption, something made possible, in part, by laws protecting Haitian farmers from the heavily subsidized rice produced in the U.S. and Europe. Twenty percent of the Haitian population was directly involved in the industry. But in the political chaos of 1986—the year that the last Duvalier regime was ousted from power—USAID used the promise of continued political and financial support to negotiate a lowering of tariffs on rice from 35 to 3 percent. U.S. rice—subsidized at a rate that varied during the 1980s and 1990s from 35 percent to 100 percent—flooded into the country.

By 1996, 2,100 metric tons of U.S. rice arrived in Haiti every week, an annual loss to impoverished Haitian cultivators of about 23 million dollars per year.[20] Haitians were not even left the luxury, at that point in time, of controlling the importation process. About half of the imported rice came in under a sweetheart contract held by RCH (The Rice Corporation of Haiti). RCH happened to be a U.S. corporate subsidiary of Comet Rice, a subsidiary of ERLY Industries, the largest rice company in the U.S., one that, according to the Washington Office on Haiti, had been investigated for possible involvement in money laundering, illegal arms deals, illegal lobbying, and that had been debarred from U.S. government contracts. But not surprisingly, ERLY had a high-rolling team of lobbyists in Washington D.C. and, despite all their earlier woes, they wound up with control of half of Haitian rice imports. As if the low taxes were not enough, the ERLY-Comet subsidiary (RCH) bribed port officials, saving themselves over one million dollars. When the Aristide administration caught them doing it in year 2000 and tried to arrest those involved, the U.S. Senate used the Haitian government’s action as part of justification for a subsequent four-year freeze on aid to Haiti. Three years later, in 2003, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) convicted ERLY of the crime. For Aristide, it didn’t matter. By that time the Aristide government was on the verge of collapse. It would be ousted the following year. For the Haitian elite it was a good thing. They would take back control of actually importing the rice. But Arkansas farmers still had their market. And Haitian farmers were still losing theirs.[21] [22]

Flight From Poverty

By the time I came to Haiti in 1990, the rural exodus that the American Plan helped precipitate was in full swing. Not unlike the generations of my own parents and grandparents in the United States, the youth were fleeing the farms. No one in Haiti wanted to be a country bumpkin. People in the towns and cities, the children and grandchildren of country folk, saw their rural cousins as ignorant and uncivilized. They referred to them as abitan (hick), moun mon (hillbilly) dan wouj (red teeth) and pye pete (cracked feet). The peasants themselves desperately sought to get their children to towns and cities to get them educated, something that fueled the restavek phenomenon seen in an earlier chapter. And it wasn’t just a social movement. The urban slums with their festering sewage might seem awful to most people reading this book, but it’s those who remained in the countryside who suffered most. They were and still are the poorest and most malnourished people in Haiti.

What a crashed rural economy and migration toward the cities meant was that everyone wanted a home in the city, no matter how poorly constructed, undesirable the neighborhood, or vulnerable to flooding the plot on which the house was built. Houses in towns and cities were the first step to getting out of rural areas. Unless one sent their children to work in the homes of family, friends or acquaintances, owning a house in town was the only way of getting children a secondary education. Even for those who still farmed, houses in town and urban areas became critical to do business and to sell farm produce on the more lucrative informal urban market. This was true for the female household head or co-heads’ who trade rural produce, bringing it in from rural areas and selling it to urban market women. And it was true for those male family members who wanted to seek temporary work in the city or to learn a trade. Having a house in the city also increased the potential for building social capital by extending hospitality to rural family, friends or neighbors who did not yet have a house in the town or city. People sometimes rented rooms or homes, but the objective was to have your own home in the city. Adults who could not afford to construct second and third houses in urban areas invested in family members who could construct one. They sought some kind of stake in the town and urban based homes of relatives, or friends. Indeed, it became unthinkable that one did not have somewhere to stay in town or the city. And the city that people wanted if not needed a foothold more than any other was Port-au-Prince.

Port of the Prince

“The Port of the Prince” is the Haitian “Big Apple,” where people are proud to live; where is located 80 percent of all secondary schools and 95 percent of universities and state technical schools; where more than 90 percent of public employees work, and 87 percent of all government expenditures are made; from whence flow all political decisions, the commandments and revolutions that have shaped modern Haitian history and where today all foreign NGOs have their headquarters. To have a house in Port-au-Prince, no matter how small, is considered the critical component to social mobility, to escaping rural poverty, educating children, getting them into the work force and, if God be willing, getting them overseas and into the US, Canadian or French work force, the holy grail for all Haitians.

As seen, it’s not true that 70 to 80 percent of households in Port-au-Prince were inhabited by renters at the time of the earthquake. It was the contrary: only about 40 percent were renters. At least 50 to 60 percent of people living in Port-au-Prince owned the house they lived in. And if we consider the rapid rate of migration from rural areas, one could conclude that just about everyone who had been in the city for any length of time owned their home. We can surmise that the 40 to 50 percent that did not own a home were relative newcomers. So if everyone is so poor, how did they get those homes? This is where so many of the humanitarian agencies and the media miserably failed to understand what was happening in Haiti. To understand that, it’s instructive to take a brief look at more distant history.

Haiti’s History of Land Invasions

In the decades following Haiti‘s 1804 declaration of independence, the only successful slave revolt in modern history, the new government attempted to restore the plantations and set the former slaves to work on them as serfs and sharecroppers. The efforts failed miserably. Revolt, flight to more remote areas of the island and passive resistance eventually meant that to generate tax revenue for the ailing state, Haitian leaders were increasingly compelled, not to take land away from the former slaves, but to give them more. They gave land to soldiers and eventually to those peons who had not already seized land. By 1842 there was no turning back. What had been the world’s most productive plantation economy—the former French Colony of Saint-Domingue—was becoming a country dominated by small peasant plots. Haiti became that country with as equitable a distribution of land as any on earth. Struggles and frequent warfare between the peasants—who had informal title to the land—and the elites—who used the formal legal system to make timber and mining concessions to multinational corporations—punctuated the next 100 years of history. The struggles were fierce and it is a fascinating history. But what’s important here is that while the poor were more often the losers of military and political battles, for the entire 206 years leading up to the 2010 Haiti earthquake they had been winning the war for land.

A thriving land market of small parcels evolved. The 1950 census found that 85 percent of farmers owned their land.[23] The 1971 census found that there were 616,700 farms in Haiti (pop 4.1 million). Average holding was 1.4 hectares (3.5 acres). Holdings typically consisted of several plots. The largest farms made up only 3 percent of the total number and comprised less than 20 percent of the total arable land. And even those were generally not big. One would be hard pressed today to find a land owner in all of rural Haiti with more than a couple hundred acres. The few vast tracks that the rich still own are precisely in Port-au-Prince. And they’ve been having a tough time holding on to them.

As the urbanization seen earlier took hold and rural immigrants increasingly moved into Port-au-Prince, the process was repeated. In this case, those left as guards and caretakers of land owned by people who had fled into political asylum or who had gone to work overseas soon began to sell it. They sold the land to rural in-migrants. Places like Ravine Pentad and Martissant—subjects of the BARR Survey—began this way. With political turmoil that followed the fall of the 1986 Duvalier dictatorship, the process accelerated. When one sees the masses of pastel concrete housing above Port-au-Prince (Jalousie)—colored with government subsidized paint—what one is looking at is 30,000 houses built over the past 20 years, and on land that was expropriated from elite, formal sector land owners.

Indeed, the ironic thing about all of this is that it’s not the Haitian peasants and slum dwellers who are insecure about land. It’s the elite. Those who suffer land insecurity in Haiti are predominantly the wealthy, largely absentee landowners who for 200 years have, as with the informal economy in general, watched the extralegal land tenure system of the poor devour their formal system. And after the earthquake they were sweating bullets.[24] [25]

“I said to myself right then, ‘Uh-oh. You’re in trouble.’ ” Haitian landowner Joseph St. Fort recounted to The New York Times journalists, “I started feeling panic because I knew it would be very difficult to get rid of them.” Wealthy land owners could not, in front of the thousands of international press cameras, activists, humanitarian aid workers and, not least of all, the United Nations with all its charters defending war refugees and migrants, start kicking “earthquake survivors” and their children out of “IDP camps.”[26]

With every NGO and U.N. employee who stepped off the plane the power of the poor grew. People poured out and staked claims on every piece of green space they could find. Many of them then rested comfortably knowing that the international community was keeping an eye on the elite and the government. Hence, the 6 months of growing camps. Even the Haitian country club where Sean Penn had set up his NGO was an attempt to fend off squatters gone wrong. The manager of the club, Bill Evans, knew exactly what was coming. Three days after the earthquake, Evans cleverly delivered a letter to the U.S. ambassadors’ house ceding the use of the country club to the U.S. military. Then Evans got on a helicopter and left. The expectation was that the ambassador’s acceptance meant the U.S. military would also be responsible for protecting the facilities from, not least of all, squatters. It didn’t happen that way. Instead of protecting the property, the U.S. army—as clueless as the press and the NGOs—turned it into an IDP camp. They began giving food and water away. People realized the land was not protected and in a matter of days it became covered with thousands of “IDPs” from the surrounding neighborhoods. And just like the rest of the camps, people would continue to erect tents on the golf course for the next seven months. None of this is to say that the director of the club, Evans, is not a compassionate person who cares about the poor. I happen to know he is. And he wound up becoming an ardent defender of the 50,000 people who invaded and squatted on the club’s golf course. But what it shows us is a microcosm of what was happening all over Port-au-Prince. [27]

Defending the Land

By October they were getting sick of it. Evans, under heavy pressure from his 300 club members, was trying to sue the U.S. government for having allowed the invasion of the golf course. And it wasn’t just elite land owners, nor even Haitians. “This used to be a beautiful place,” U.S. Church of God missionary Jim Hudson told New York Times journalists. After the earthquake the church had “shared meals” with 4,000 people who sought refuge on the property. Ten months later 500 of them refused to leave: “… these people are tearing up the property,” Hudson complained. “They’re urinating on it. They’re bathing out in public. They’re stealing electricity. And they don’t work. They sit around all day, waiting for handouts.”

On July 14, 2010, precisely at the height of what some elite were calling “the other occupation”—as opposed to the UN occupation—Sharif Abdel Kouddous of Democracy Now would report that:

…this issue of the land…is at the crux of the matter, when we were in Port-au-Prince, that’s what everyone was saying: Where are all these people going to go? These tent cities literally are on every street in Port-au-Prince, just teeming around the city. And from aid activists—-from activists to people on the ground, organizers, community organizers are all talking about this issue of land: Where are all these people going to go?

Abdel Kouddous. Democracy Now. July 14 2010[28]

The ever-perspicacious Kim Ives responded:

…the principal fault-line in Haiti is not geological but one of class. A small handful of rich families own large tracts of land in suburban Port-au-Prince which would be ideal for resettling the displaced thousands […]. However, these same families control the Haitian government and, more importantly, have great influence in the newly formed 26-member Interim Haiti Reconstruction Commission (IHRC) […]. The IHRC is empowered for the next 18 months under a “State of Emergency Law” to seize land for rebuilding as it sees fit […], but the elite families on this body in charge of expropriations are not volunteering their own well-situated land to benefit Haiti’s homeless.[29] [30] [31]

Kim Ives. Democracy Now. July 14, 2010

The elite were under serious pressure. Every activist group in Haiti would soon be talking about the right to housing. Illustrating where all this was to lead, on the second anniversary of the earthquake a coordinated onslaught of speeches and press releases from nine of Haiti’s most active activist organizations were summed up in a joint statement:[32]

We raise our voices to denounce with all of our might, before the national and international community, the threat of forced eviction…. We ask all the institutions involved (the president, the government, the mayor, NGOs assisting displaced people, human rights organizations, etc.) to press, press our case … to respect the rights that we have as people. As Article 22 of this country’s constitution and Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declare, “All people have the right to housing.”

January 12, 2012, Joint press conference of the

International Lawyers’ Office (BAI) and residents of Camp Mariani

Even KOFAVIV ladies turned from rape to housing, cleverly blaming the rape on the lack of housing:

As in other countries, good human principles and protocols that humanitarian organizations and the state need to apply have been established. But we observe that in Haiti up until today, these principles are being trampled on, causing women and young girls to be ever more exposed to rapists.

[Eramithe Delva and Malya Villard-Apollon], Tectonic Shifts, 2012:164

If 1.5 million people had decided to defend their claims in camps, there would have been nothing anyone could do to get them off the land. And with the humanitarian community bound to respect international standards, they would have had to protect the poor against eviction. But the elite had been one step ahead of them all. In March 2010, a scarce 3 months after the earthquake, they had already come up with the answer that would largely defuse the land invasion: Canaan.

Canaan: Land of Milk and Honey

In March 2010, while the Camps were still growing, word began to leak out that the Haitian and U.S. governments were planning a new city at Corail-Cesselesse, a 30-square mile swath of land to the north of Port-au-Prince. It seemed perfect. If before the earthquake one had stood on the mountain above Port-au-Prince and looked down, one saw below the most densely populated city in the Caribbean, a sea of concrete slums. But then, looking to the North, on the far side of those slums, was Corail-Cesselesse, a vast swath of empty land. It began on the plain, extended up the foot of a different mountain range and into the unseen heights of Haiti’s Central Plateau. All empty. Impoverished Haitians would soon call it Canaan, after the biblical land of milk and honey that God gave to the Israelites. It was, however, no land of milk and honey. [33]

The reason it had been empty was that there was not a single spring nor source of water. No shade trees. Yet, with the Haitian government leading the charge, the plans for a “Zen city” began to form. Transitional shelters, the government declared, would be built for 300,000 people. Each would have a permanent frame that could be expanded into a six-room house. In the midst of the neighborhoods global investment firms would build garment factories, stores and restaurants. The rumor was that Bill Clinton backed the plan. The U.S. State Department was on board. Indeed, it seemed that everyone was on board: UNICEF, World Food Program, The American Refugee Committee, The Red Cross, CRS, World Vision, Oxfam, Save the Children, Samaritan’s Purse. “The idea,” a smiling senior Haitian Government advisor, Leslie Voltaire, told Associated Press journalists, “is to pick up all that imagination and wealth and put it in that mountain… It’s going to be a hit.”[34]

The new Canaan was kicked off with a planned community of 2,000 homes. The U.S. military bulldozed the land. Sean Penn’s NGO (JP/HRO) began an info drive to get people to voluntarily leave the golf course and move to Canaan. Calling it the “Beat the Rain campaign”—a reference to escaping the torrential seasonal rains in Port-au-Prince—Rolling Stone journalist Janet Reitman recounts:[35]

On Saturday, April 10th, 2010, the first group left the golf course in a caravan of buses, the exodus chaperoned by United Nations peacekeepers. They arrived, disembarking onto a dusty, cactus-strewn patch of land in the shadow of a denuded mountain … Their new homes—bright white tents set up on the baking gravel—were both hot and flimsy; three months after the refugees arrived, hundreds of the tents would blow away in a heavy windstorm. There were no schools, no markets, and the closest hospital was miles away. There were also no jobs… To return to the city meant a long walk to a bus stop followed by a several-hour commute. They were marooned.[36]

Rolling Stone 2011

Two weeks after the windstorm, IOM issued a report that major sectors of Canaan chosen for settlements were “prone to flood and strong wind… flooded regularly at least once a year.” In other words, it was a barren and dry desert that, when it did get rain, flooded. By that point in time Samaritan’s Purse had built hundreds of shelters in an area where water had to rise 14 inches before it even began to drain. World Vision had done the same. And it would get worse. USAID consultant Bill Vastine explained to Reuter’s journalist that one site, “had an open-mined pit on one side of it, a severe 100-foot vertical cliff, and ravines.”[37] [38]

There were lot of regrets and blame deflection. UN-Habitat director Jean-Christophe Adrian lamented that they had “opened a Pandora’s Box.” World Vision representatives “felt the process was rushed.” Julie Schindall of Oxfam told journalists, “I have no idea how they selected that camp. It was all done very last minute—we had to set the entire structure up in a week.” American Refugee Committee (ARC) director Richard Poole, disavowed ARCs role overseeing the movement of people into Canaan, saying, “ARC did not have a say in the planning of the Corail Camp” and went on later to dismiss the project entirely saying, “the location of the camps far from Port-au-Prince with little or no prospect of economic activity was a mistake… Without an economic base, however, the plan was doomed to fail.” Similarly, Hélène Mauduit of Entrepreneurs du Monde would say that “sure, there are shelters, a hospital and a school, but there is no future for the people of Corail (Canaan) because there is no work, there are not roads and there’s no electricity…They either need to destroy it and put people somewhere else, or they need to say to themselves, ‘Ah, these are human beings who live at Corail!’ ” Typically candid Sean Penn would tell Rolling Stone journalist Janet Reitman, “I feel like shit. I hope those guys are OK when it rains out there. I feel an extra responsibility—of course I do. But we were betrayed.”[39] [40] [41]

The bottom line was that those international humanitarian workers who really were trying to help the Haitian poor, like Sean Penn, had been duped. They had been duped by the poor, they’d been duped by the rich, and they’d duped themselves. They’d been duped by the poor in that most of the people in camps did not go there because they had nowhere else to go. They went to the camps because of the opportunities, most importantly the chance to own their own home in Port-au-Prince. They had been duped by the government and the rich because when they tried to help the poor get homes they wound up initiating a massive migration onto land unsuitable for human habitation. And they had duped themselves because the international players in all this were never going to make huge investments in housing. They were too busy spending the money on themselves, their own salaries, administrations, rental cars and consultants. There wasn’t enough money to give housing to the poor. Indeed, none of the humanitarian organizations, nor the government lived up to their promises to pay for the original $64-million piece of land.

The land that was the original Corail was owned by a corporation called NABATEC, a small consortium of Haiti’s super rich. Gérald Emile “Aby” Brun the president of NABATEC described the agreements that morphed into a massive land invasion as a, “15-year, US$2 billion project, and everyone had already given their approval, including the Haitian government and the World Bank.” In that way, at least some of the Haitian elite got duped as well. NABATEC claimed to have spent over US$1.5 million on the project. They never got a dime. In 2013, three years after the land had been completely overrun and all hopes of developing it dashed, Brun would lament. “A dreamed of new city was killed by narrow minded and greedy people, under the tolerant observation of the international community.”[42]

There would be no Zen city. No factories. No up-scale NGO conference centers. Not at Corail-Cesselesse. But the most fascinating thing about it all, and what most Haitian elite understood all along, is that it didn’t matter. The government and its announcements coupled with a mysteriously zero defense of land meant that, by that point in time, the 10,000 squatters had been joined by another 40,000. More were coming every day. They swarmed onto the land. By the first anniversary of the earthquake there were more than 100,000 people. “It was like the gold rush,” a UN official told Rolling Stone journalist Janet Reitman. “Within about a week of people moving to Corail, you had all these other people rushing out there to stake their claim. People were up there buying and selling plots of land—completely illegally.”

One of those people was Vilmond Joegodson, seen earlier describing the opportunism in the camps. In May, Joegodson left his camp in Port-au-Prince and with his fiancée made his way to Corail-Cesselesse. His cousin had a friend who’d claimed some plots of land and was selling them for 1,000 Haitian dollars (US$120 at the time). Joegodson and his friend Paul Jackson described the process,

The first squatters to arrive in Canaan claimed their land as did people in such camps all over Port-au-Prince: they placed posts at the corners of their plot or drew a border around a site with rocks. Once they had their own land, the speculators would then trace out secondary and tertiary plots that they would be able to sell to newcomers as time progressed. It was as simple as making a parcel of land look inhabited. By general agreement, that was accepted as ownership …..

As bulldozers flattened the fields and constructed rudimentary facilities, the speculators started to cash in. At one point, a plot of land was selling for 100 Haitian dollars, about $US 17.00. Now, they are going for ten times that price… However, the buyers get no deed in return for paying the speculators who simply remove the signs of occupation and welcome the newcomer to the neighborhood.

Joegodson and Jackson, 2015[43]

And it is here, in this massive land invasion, and not in the free tents, food and water the NGOs were giving away, that we can understand what was ultimately driving the camps, as well as the government’s dream of a Zen city, and the failure of the resettlements.[44]

Corail-Cesselesse was nothing less than a tactical ruse. The most useless land in all of Port-au-Prince; half flood plain, half barren and dry land, it was fit only for goats. But it was arguably a necessary ruse. And this is what the international participants and the press never seemed to get. When Paul Jackson asked Joegodson, “What if the state decides that it doesn’t want people in Canaan?” His answer, “Too late, says Joegodson on behalf of everyone that is in his position. It would mean civil war if the state tries to clear all of these communities…”[45]

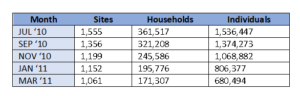

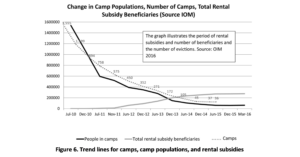

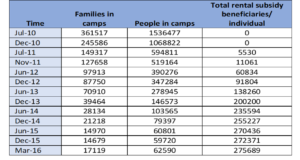

And that was indeed the crux of it. Without a place to go, without Canaan, it would have been civil war in Port-au-Prince. The elite would have had to give up their land in Port-au-Prince or there would have been widespread rioting. And this is where the tide switched. The poor had used the earthquake and then the incursion of the NGOs, not so much for the services they gave out—most of which, aside from medical care, were relatively meaningless as the poor could have managed without them, such as in the case of water—but in a bid for a piece of land in Port-au-Prince on which to build a house. Indeed, that was the poor’s ruse, albeit one that the humanitarian agencies eagerly latched on in promoting their own interests—donations. The poor capitalized on their perceived needs, none of which are met any better today than they were before the earthquake. The humanitarian aid agencies, the activists, and their journalist allies became international leverage for the poor: their brokers in a humanitarian claim to land. Because of the zeal with which both advocates and humanitarian agencies accepted and even defended the legitimacy of the “IDPs” it made those claims good for everyone. It made them good for renters who did not own a home in Port-au-Prince, good for any of the millions of rural people who wanted to come to live in Port-au-Prince but could not hitherto afford to, good for the many living in Port-au-Prince who owned homes in the worst neighborhoods and wanted to move, and good for those who wanted second homes or rental properties. It was a massive opportunity. But now, with Canaan, everything changed. The promise of a “Zen City” and the massive land invasion that followed, siphoned off hundreds of thousands of people. By January 2011, IOM estimate for people in the camps was down to 1 million. By March it was down to 680,000.

The Almost Breaking Dam

Although the camps had been significantly reduced in population, they nevertheless remained a massive problem for the aid agencies. As seen, the humanitarian agencies had little real impact. The aid they brought was being embezzled and siphoned off. The impact of what they did deliver was highly questionable. And it wasn’t long before some journalists, smelling a good story, turned on the humanitarian agencies and began to ask where all the money went. And with good reason.

The humanitarian aid agencies didn’t know how much to spend on what and where. They gave out 96,000 tents; 38,000 of which went to the people of Jacmel, a town of 36,000 people where, contrary to official estimates, more than 95 percent of homes came through the earthquake in nearly unscathed condition. Twelve weeks after the earthquake, in rural Leogane, ground zero for the earthquake, 300 empty, tattered and wind-torn tents flapped in the breeze, no sign that they had ever been inhabited. At an average of $2,000, it was $600,000 squandered aid dollars. A few miles down the road from the tents, 100 transitional shelters, empty. At a cost of $5,265 a pop it was another 526,500 wasted dollars. Six months later they had vanished entirely and a private orphanage stood in their place. In downtown Port-au-Prince, in September 2010, nine months after the earthquake, Camp Jean Marie Vincent had 48,000 inhabitants living in scrap wood and makeshift shelters with a grand total of 115 latrines—421 people per latrine. Across the street sat 518 new tents and 150 latrines with showers, all empty. The latrines and showers would never be used; the tents would never be inhabited. Six months later the government would replace them with a warehouse. Those are the ones that I know about. That I actually visited. And that’s only tents. [46] [47] [48]

Much of the aid that was given away was indicative of an appalling lack of cultural understanding. The sub-director of Save the Children, which had gotten $87 million in donations, told me, “They gave me 30 million and told me I had to get rid of it in six months.” She drops her jaw and looks at me as if to emphasize the absurdity of the task. With a “Hmff” she went on to tell me about a guy in her office who bought 2,000 basketball hoops for the camps. Ninety percent of Haitians have never played basketball; they play soccer, and most camps had nowhere to put a basketball hoop. “It was surreal,” she continued, “We had them under our desks, in the closets.”

Save the Children, as well as World Vision, Catholic Relief Services and UNICEF, decided to spend unknown millions of dollars of donor money setting up “child-friendly spaces” where children could come and spend hours each day relieved of the stresses of daily life. Calling them a “sustainable solution,” UNICEF alone claimed to have provided such spaces to “almost 100,000 children.” But the idea of temporarily relieving children of stress while not even giving their parents a job cleaning up rubble or injecting the money meant for victims of the earthquake into the local economy is not only unsustainable, it’s an absurdity.[49]

Those who work for the child protection agencies and read the above will surely cite the importance of babysitting the children for their parents. And I know that might sound like a good idea to people in developed countries. After all, for those of us who have children, paying for daycare is expensive. And after such a terrible earthquake, free childcare might be a good thing. But UNICEF, Save the Children and World Vision—three agencies that collectively have 120 years working in Haiti—should know better. Free childcare to the poor in developing countries is an oxymoron. That’s not the way culture operates in developing countries. With regard to Haiti, we’re talking about a country where the average child has a grand total of 50 close relatives who could care for them. We’re talking parents, grandparents, godparents, siblings, half siblings, uncles, aunts, and first cousins. I’m not making this up. I’ve calculated it (see the notes). Most of those people are not just glad to care for the children, they’re eager to. Haitians are raised looking after each other. And we’re talking about a moment in time when most were out of work and sitting around with nothing else to do. Indeed, Haitians were up to their ears in people who could baby sit. They did not need the NGOs to do it for them.[50] [51]

And then there was millions spent on therapy, such as the case of the Red Cross which, with all their different branches, had collected $1.2 billion. The Red Cross only provided 814 portable latrines to 27 camps, but they claimed to have provided psycho-social services to 93,484 people.[52] The therapy was overwhelmingly conducted by “experts,” many of whom had never met a Haitian in their life before the earthquake. As seen in Chapter 8, Haitian social worker Maile Alphonse, goddaughter of Canadian Governor General Michaelle Jean, quizzically complained to me:

These foreigners, they come here and they want to go into the camps and do therapy. They don’t speak the language, and they don’t know the culturally patterns expressions of frustration and stress. They don’t know anything about the culture. They go in with a translator. You can’t do therapy with a translator. They have their pet therapies…. And they don’t want to work with the Haitian organizations and the people that have been doing this work.

As for the services to the people in the camps, in reality it wasn’t clear who spent how much and on what. In explaining to donors, the NGOs almost always listed the same four categories: food, water, sanitation, and shelter. But with no details. They lumped “latrines, showers, and water distribution points” in sanitation. They threw blankets in with “shelters and kitchen utensils…” They referred to feeding tens of thousands of people without pointing out that they may have fed each of them just once. The Red Cross provided water to 100,000 people. What did that mean? Was it a single bottle of water to each of them—which means that if they really did need water they would have died from thirst in three days anyway—or was it a truck of water to a camp with 100,000 people? They listed millions of liters of water. What does that mean? Did they spray it from a truck? I happen to know that in most cases the answer is yes, that’s exactly what they did, sprayed it into buckets from a truck. Actually, in most cases it was not even the humanitarian aid agencies that did it. They paid private water trucks to deliver water. And most of that water was not potable. When they said clean water, that usually meant water purified with tablets or chlorine. It might still sound impressive to someone sitting in an apartment building in Philadelphia: ‘1 million liters of potable water.’ It is not impressive. I could have reached into my own pocket for one week of consultancy fees ($2,500), and done the same thing, provided 1 million liters of potable water. Here’s the math: forty-eight 5,000-gallon trucks of water at $50 per truck for a total of 960,000 quarts/liters of water and then with the remaining $100, two-hundred $0.50 liters of bleach and presto! I’m as big a water distributor as the multinational aid agencies. And then there were those NGOs that were even more vague, such as Mercy Corps, recipient of $21.6 million, which did not give any breakdown on their expenditures at all, saying only that they had “provided emergency assistance to help 830,000 people after the devastating Haiti earthquake.” What in the hell does that mean? And for those who think all you had to do was call them up and ask for clarification, think again. As seen in the introduction, they wouldn’t respond. Out of 196 NGOs that Disaster Accountability Project wrote and inquired about specific expenditure, 176 would not respond.[53]

Just as with the rapes and orphans, there came a point in time where it seemed like the dam would burst and the aid agencies would have to fess up to what they’d done with the more than the 1.2 billion spent on the camps. It was about that time, the first year anniversary, when just over half of the aid money that donors had entrusted to humanitarian aid agencies had been spent, that the press corps turned on their humanitarian allies. Questions and critiques became a chorus, of “Where did the money go?” Advocate-journalists inundated newspapers with the phrase. Major publications unleashed a slew of articles condemning the earthquake aid as a failed undertaking.[54]

“Who Failed on Haiti’s Recovery?”[55]

TIME, January 2011

“NGOs Have Failed Haiti”[56]

NPR, January 2011

“Where Haiti’s money has gone”

Reuters, August 22, 2011[57]

“How the World Failed Haiti.”

Rolling Stone, August 2011

But the proverbial dam did not burst. By mid-2011, with the vast majority of the aid money almost gone—mostly into the pockets of consultants, therapists, aid workers, the bank accounts of the Haitian elite who were gouging them all, and the coffers of NGO and UN headquarters with their overhead expenses as high as 50 percent (something they almost all cleverly lie about)—IOM announced the end of support to the camps. They quit collecting trash. They quit pumping out the toilets. They quit delivering water or cut off what water was available to different camps. According to Professor Mark Schuller who had become an advocate for people in the camps:

… the “free services” that ostensibly were the magnet to the camps—notably water and toilet services—were being shut off as NGO contracts ended. As of October 2011, only 6 percent of IDP camps had water services, and in November water trucking services had to stop per government decree.[58]

The January 2012 WASH Cluster (UN/OCHA) report found that in only seven percent of camps was solid waste being collected and disposed of. In 72 percent of all camps those conducting surveys saw solid human waste visible in the camp. Of over 600 camps, there were only 81 where latrines had been emptied in the previous month. At the same time pressure from landlords increased. In some camps thugs invaded, throwing rocks, and setting tents afire.

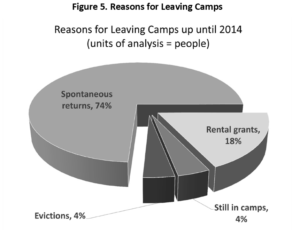

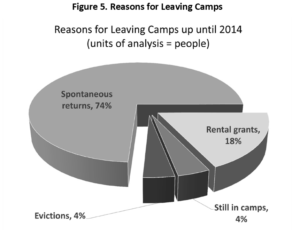

Spontanesouly Disappearing IDPs

By December 2012 there were 347,284 people in the camps, down from the 1.5 million IOM had said were living in camps six months after the earthquake; 74 percent of them had simply left the camps, “spontaneously” according to IOM. It was not clear how many of the remaining thousands were holding out to see if they could keep the land they had their shelter on. Most revealing, over 90 percent of those who were still in the camps had been renters before the earthquake. But victims of the earthquake or not, the humanitarian aid agencies could not leave them as a reminder to the world of the failed post-earthquake relief effort. And so, a new plan was hatched.

In a strategy that critics denounced as “paying off the poor,” 80,000 families (representing 250,000 people) were given $500 toward a year’s rent. To make sure they really left the camps, the contract for the money was often given, not to the family, but to the owner of the rental unit where they were supposed to go live. The family had to move; then the tent was torn down; and then the money got transferred. Some 2 to 6 weeks after the move the aid agencies sent people in to verify if the people had really moved into the rental unit, and not simply partnered with a landlord to game the system. And in a move that seemed targeted to assure anyone who was lying to continue to do so—I by rewarding them for having lied in the first place–, they gave the recipients another $125—if they appeared to still be in the house.

How many really did move into the homes isn’t clear. The NGOs and UN claimed fantastic success rates. Red Cross evaluators found the results “extremely promising” explaining that “one year on, no grantees have returned to camps and 100 percent have autonomously found an accommodation solution.[59] Similar results can be found from evaluators for all the aid agencies, “100% satisfaction”, “90%” of all recipients really moved to the houses.”[60] [61]

Behind the scenes it wasn’t so pretty. In 2016, I was hired to lead a team of researchers for the United Nations Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster (CCCM Cluster), an agglomeration of 10 of the biggest humanitarian organizations involved in the rental subsidy program. Our task was to review their internal reports and then design and conduct a survey of 1,400 of those who had received rental subsidies. The American Red Cross—under fire at the time for the now famous NPR investigation that revealed they had, despite getting $500 million in donations for Haiti earthquake victims, built a total of 6 houses—wouldn’t even give us the lists to find their beneficiaries. Neither did Sean Penn’s organization JP/HRO, which had spent some $8 million of World Bank funds to provide rental subsidies. When you read between the lines the deception was abundantly in evidence. Alexis Kervins, who managed the data for JP/HRO follow-up verifications, told me that 60 percent of the recipients had never even moved into the homes. In the survey we conducted for the CCCM Cluster, 80 percent of the phone numbers that the NGOs gave us on the contact lists were no good or no longer working.[62] The World Bank would note in its 2014, Rental Support Cash Grant Programs: Operations Manual that, “one interviewee gave some idea of the scale of the challenge when he noted that of 600 complaints received following registration at one camp, 70 were found to indeed live there.” In what was one of the few examples of a verifiable beneficiary list, Concern Worldwide wrote in an internal report that:

Over 3000 persons declared not having any ID during registration; however verification by local organisation ACAT (contracted to provide birth certificates) found that the great majority of those persons do in fact have ID. ACAT’s verification brought down the number of paperless beneficiaries to 379 ….[63]

In retrospect, the camps were one more version of the Great Haiti Aid Swindle. And just as with the rapes, orphans, the number dead, and all the other hyped afflictions the humanitarian aid agencies used to collect donations, they justified them with bad data, truth stretching and lies, all needed to fool the overseas public and legitimize the aid that was pouring in. The aid agencies knew what data was in their best interests and what was not. When the numbers didn’t add up, they came up with new numbers Was it impossible that 43 percent of the population were in camps? In one of the first major reports on the camps, U.S. university professor, activist-anthropologist and humanitarian aid researcher Mark Schuller claimed that 70 to 85 percent of the people in Port-au-Prince had been renters before the earthquake. It was a number that got picked up by aid agencies and became part of the narrative. But Schuller had, deliberately or otherwise, mis-cited his colleagues Deepa Panchang and Mark Snyder who in a report had said, not 85 percent, but rather “up to 70%” of people were renters. And they were not referring to the population of Port-au-Prince. They were referring to people living in the camps. Meanwhile, the real figure for proportion of the population that was renters at the time of the earthquake was, as seen, 40-50 percent of Port-au-Prince households, a figure that was available in several major and widely known studies. [64] [65] [66] [67] [68] [69] [70]

Another myth that justified camps was “skyrocketing rental costs.” Once again, this untruth came from the prolific Professor Schuller who by this time had dubbed himself the “professor of NGOs” and was traveling to Washington D.C. to brief congressional committees on earthquake expenditures. Schuller cited UN data that rents had increased 300 percent since the earthquake, data that the aid agencies again latched on to. Yet, using real income indicators, rental prices in Port-au-Prince slums where the same in 2010, 2011, and 2012 as they were in 1982 when author Joegodson’s father paid the equivalent of $209 for 1-year rental of a one-room, dirt floor shack with no latrine in Cite Soleil—one of Port-au-Prince’s poorest slums. As for the 300 percent increase in the cost of housing, Professor Schuller had been citing a UN report. But the UN wasn’t talking about the poor. They were talking about their own personnel who, along with NGO workers and consultants, were getting gouged while the rest of us who lived in Haiti, in popular neighborhoods, continued to pay the same rents.[71] [72] [73] [74]

Conclusion: behind the Greed and Negligence

The misunderstandings, the failure to reach many of the most vulnerable, the lies about the numbers, the lies about opportunism, and the exploitation of the camps as “aid bait” to draw in donations were major features of the Haitian earthquake relief effort that should not be forgotten. Just as with the rescues, the orphans and the so-called rape epidemic, we shouldn’t allow politics, self-interest and headline hunting journalists to impede our capacity to learn from the failures that came after the earthquake. But it’s important to make clear that the process is not some kind of conspiracy to mislead donors and benefit aid workers. Most aid workers who were present—from the lowest field worker to the highest directors—were as dismayed as I am with the waste, with the money that seemed to vanish, and with the failure to reach those who were most in need. And many of the lowest level aid workers did not earn fat salaries. There were thousands of missionaries who earned nothing at all. There were people who paid to come to Haiti, who simply got tired of seeing the thousands of suffering Haitians on television, got off the couch, bought plane tickets, and came to Haiti to try do something about it. And even the high-level directors and administrators of humanitarian aid agencies are mostly good people who believe in what they are doing. I’ve known hundreds of them. The clear majority are compassionate people who set out to help, who wanted to change the world, alleviate poverty and suffering. But as they advance in the corporate world of charity, they get caught up in the industry of aid, the dreams get swept away and replaced by hope for a salary raise, a pension plan, a promotion, better working conditions, and the very real need to care for their own families. Turning on your employer and revealing that aid is failing is a fast way for an aid executive to lose those perks and get booted out of the business they and their families have come to depend on.

So it’s not the aid workers that we should blame for the failures. The issue is ultimately one of accountability. Those mega-aid institutions such as CARE International, Save the Children, and UNICEF depend on donations. The directors’ salaries and pension plans depend on those donations. The capacity for the organizations to be present in poor countries—no matter how wasteful and ineffective the organization is—all depends on getting donations. Their dependency on that money means the aid agencies must be pumping the public and the press with information that encourages people to give; their bureaucratic inefficiency means that there is never enough money; and the total absence of any mechanism to make the organizations accountable assures waste and failure to get the money to those for whom the aid was intended. There are no institutional benefits to resolving these problems. There is no mechanism that assures that the organization that most effectively spends the money and helps people out of poverty will get the most money. On the contrary, It’s not about effectively spending the money; it’s about getting the money. The most donations go to those who exaggerate and lie the best. The profit motive is getting donors to give, selling images of extreme need and suffering: vulnerable children, orphans, child slaves, rape victims, homeless people. And they need that money to keep going, to keep the directors paid, keep the organization alive. It’s those needs that assure the problems will be exaggerated and the accomplishments, no matter how pathetic, will be hyped. It assures they will always hide the truth. And no matter how ineffective an aid agency is, those idealists working for the organization can always latch on to the belief that yes, there were mistakes in the past, but it’s all about to change, and they’re part of that change. But you can’t make change happen if the money stops. And in what becomes a fierce competition of making afflictions up, a type of arms race of lies, the money goes to those with the most fantastic tales. And so in the absence of any mechanism to vet those lies and censure those organizations behind the lies, the experts and professionals go right on pumping out untruths and sabotaging their own efforts to help the poor.

NOTES

[1] “I don’t think they are really hungry.” Maria, the woman from Honduras also said, and she was not being insensitive. She understands that they are poor. She has already said, “they are so poor, they are desperate.” But she’s perplexed, “It’s like this is what they do, it’s like some kind of opportunity.”

[2] For quotes and accounts from Joegodson see, Deralcine, Vilmond Joegodson and Paul Jackson. 2015. Rocks in the Water, Rocks in the Sun: A Memoir from the Heart of Haiti (Our Lives: Diary, Memoir, and Letters Series) Paperback – April 23, 2015.

[3] For the building structural evaluations see, Miyamoto, H. Kit Ph.D., S.E (Seismic Engineer)., and Amir Gilani, Ph.D., S.E 2011 Haiti Earthquake Structural Debris Assessment Based on MTPTC Damage and USAID Repair Assessments. Miyamoto International

[4] Data from IOM on home returns by month and year for 2010 and 2011:

[5] Most of the controversy over the BARR Survey centered on the death count. But we also estimated that only 1 of every 20 people in the camps came from earthquake impacted homes. Indeed, that might have been the biggest reason that USAID in Washington had reacted so strongly to the release of the report. As Professor Mark Schuller would unwittingly admit when attacking it, “a red herring.” What was really at issue was the legitimacy of the camps. Schuller would write:

… the attention deflected away from this discussion of the “illegitimate” IDPs, was an insidious outcome. With the public debate focusing on what to most Haitian people I know consider a red herring—with nothing to be done about the dead, no one ultimately responsible for their deaths – the inflammatory and controversial allegations about living IDPs, whose rights were actively being challenged by a range of actors, became tacitly accepted by the lack of scrutiny.

….

To the oft-repeated quote – amplified and justified by the Schwartz report [the BARR]– of people suddenly appearing in unused tents whenever a distribution was made, my eight research teams spent five weeks in the same camp and noticed a constant level of comings and goings, economic activity, and social life. In other words, they were all “real” camps.

(see, Schuller, Mark. 2011. “Smoke and Mirrors: Deflecting Attention Away From Failure in Haiti’s IDP Camps,” Huffington Post, December. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mark-schuller/haiti-idp-housing_b_1155996.html )

[6] If we had listened to the government death count estimates and the camp estimates, that would have meant this: in July 2010 there would have had 1.5 million people in Camps, 800,000 more in rural areas or homes of others, and another 316,000 dead, for a total of 2.616 million people out of a population of 3.4 million, 76 percent of the population. And yet the survey indicated that as of July, 75 percent were back home. So if 75 percent were back home, and 12 percent were dead, we had an extra 2 million people.

[7] Lest anything be misunderstood in the main text, here is what we found out from the BARR Survey—the one seen in Chapter 5 on the death count—and corroborated from data from Columbia University and Karolinska Institute, was that immediately following the earthquake, 68 percent of residents of greater Port-au-Prince left their homes. Of that we know that in the weeks immediately following the earthquake:

- Nine percent went to the homes of others

- Twenty-one percent moved into the yard or the street in front of their home

- Twenty-six percent (between 465,246 and 584,754) people left Port-au-Prince and went to stay with family in the countryside

- Forty-four percent concentrated in the spontaneous tent cities that appeared throughout the metropolitan areas.

What this means in terms of numbers is that between 866,412 to 894,588 ( p<.01) people went to camps.

But by July—when OIM and most newspapers and the Haitian government were reporting 1.5 million people in camps—75 percent of those who left Port-au-Prince were back in the city. And from the BARR Survey we knew that 66 percent of all those who had left their homes were back in their residence or in some kind of shelter on the property. That includes people who reported having gone to camps.