Here I want to show how Bongaarts and Potter’s (1983) “proximate and intermediate determinants of fertility” are inconsistent with ethnographic reality in the early and mid-20th century Caribbean. To do this I examine one of the great demographic mysteries of the Caribbean: the irony of increasing birth rates when fewer men were present, i.e., fewer men, more babies. By looking at the fewer-men-more-babies phenomenon, I believe that I can provide a graphic example of the utility of other materialist explanations for changes in fertility rates while demonstrating the inapplicability of the “proximate and intermediate determinants of fertility.” I believe that I can also show how the tension between the economic value of children to women and men and the need to get children through the critical early years determined the particular values associated with the Caribbean sexual-moral economies and high birth rates [note 1].

Proximate and Intermediate Determinants of Fertility

The first scholars to discuss the “the proximate and intermediate determinants of fertility” were Kingsley Davis and Judith Blake (1956), who identified fourteen determinants. Twenty-seven years later, Bongaarts and Potter (1983: 163–65) reduced the number to nine. The first four were the “proximate” determinants:

- Fecundity—the ability to have sexual intercourse, the ability to conceive, and the ability to carry pregnancy to term,

- Exposure to the risk of pregnancy— sexual unions, such as marriage, and the actual time that partners spend together,

- Birth control methods—contraceptives, sterilization, coitus interruptus,

- Abortion.

There were five “intermediate determinants” of fertility, those factors by which the “proximate determinants” are altered and that fall soundly in the realm of social behavior:

- Postpartum taboos—such as sexual abstinence for new mothers,

- Duration of breast feeding—nursing suppresses ovulation,

- Delayed marriage—many societies have strong norms against young women engaging in premarital sex,

- Disruption of union via male out-migration or military service, and

- Attitudes toward contraceptives and family planning.

Over the ensuing three decades social scientists came to treat the “proximate and intermediate determinants of fertility” as demographic laws. Social scientists working in the Caribbean were no exception, particularly regarding male wage migration and the resulting male absenteeism so widespread in the Caribbean. They frequently assumed and even calculated—without empirical support—the dampening effect that male out-migration supposedly had on birth rates among the women staying behind (Murthy 1973; Blake 1961: 249–50, 1954; see also Denton 1979; Williams et al. 1975; Lowenthal and Comitas 1962: 197; Ibberson 1956: 99; McElroy and Albuquerque 1990; Brockerhoff and Yang 1994).

The problem is that while seemingly obvious, the assumptions underlying the “proximate and intermediate determinants of fertility” were based on Western middle and upper class courtship behavior, where marriage, or at least stable union, was the criterion for sexual reproduction. They do not always apply in other societies; in the impoverished Caribbean, they do not apply at all, as illustrated in the fewer men, more babies phenomenon.

Fewer Men, More Babies

Gearing (1988) in Guadeloupe, Marino (1970) in the Commonwealth Caribbean, Guengant (1985: 48, 70, 103) in Montserrat, and Brittain in St. Barthelemy (1990) and again in St. Vincent and the Grenadines (1991a) all demonstrated unequivocal, positive, time-ordered correlations between total fertility rates and migration-induced male absenteeism. In each case, fertility increments closely followed the onset of migration with lags varying from zero to five years. This phenomenon appears even more remarkable when taking into account the degree of male absenteeism; male wage migration meant that there were sometimes as many as twice the number of reproductive-aged females versus males on home islands. Yet, women were having more and not fewer babies [note 2].

The simple and prosaic explanation for this phenomenon is money. The more wealth available to men, the more disposed Caribbean parents, particularly older women, were to permit sexual access to younger women and the more disposed women already engaged in their reproductive career were to acquiesce themselves, providing the impetus that explains why in times of high wage migration, more women among the impoverished Caribbean class bore more children, i.e. there was more money to meet the demands women and their families attached to sex and procreation and that was necessary to feed and care for a child until he or she became a contributing member of the household. But while the explanation might seem simple, the insights we can gain into Caribbean family patterns through focusing on the transfer of money from men to women is profound.

A look at child nutrition and mortality rates illustrates the gravity of the problem that faced lower-income Caribbean families. In 1890 Grenada, for example, half of all infants died before their first birthday; in 1896–1897 Jamaica, 17.6 percent of infants died in the first year of life and 26.8 percent of children died before the age of five; in 1952 Martinique, infant mortality was 23 percent (Brereton 1989: 103). dependent on child labor. In Jean Rabel Haiti malnutrition levels in the 1990s approached 40 percent for children six to seventy-two months of age and 25 percent of children die before they reach five years of age (see Schwartz 2009). Thus, rearing young children to the ages when they were most likely to survive and when they begin to make contributions to household production was difficult. For obvious reasons money made child survival more probable; money was used to support women during pregnancy, to help account for lost labor of the mother, and to nurture young children through to the ages where they were no longer extremely vulnerable and began to become net producers. And money could most readily be garnered from baby fathers—rather than uncles or grandfathers—because baby fathers were selected precisely for their capacity to provide financial support.

In understanding the importance of investments in young children, Jean Rabel, Haiti serves as a valuable case where data not available in the past ethnographic record can be partially recovered. The value of child labor and the stress that children experienced prior to reaching the age where they begin to contribute to the household labor pool was captured in the term chape, a frequently used local term that conceptually integrates both the passage of the vulnerable years of childhood and the entrance into the age of productivity. Chape literally meant “to escape,” and in this sense connoted the danger that a child passed through early on in life. The child was considered to chape when he or she has passed that point where death from malnutrition is most likely. But it is also at that point in the child’s life “when he can do for himself” (li ka fe pou kont li), “when he can wash his own clothes” (lè li ka lave rad pa li), when he can “get by” (lè li ka boukannen),3 “when he can go to the water by himself” (lè li ka al nan dlo pou kont li), and just as importantly, when he or she begins to contribute to the sustenance of the household. Respondents in the 136-household survey of opinions regarding children and household labor tasks explained the process,

Oh, why does a person have children? You have children. You struggle to chape them. . . . You raise them. They chape. Tomorrow, God willing, if you need a little water, the child can get it for you. If you need a little firewood, he can carry it for you.4 (fifty-five-year-old father of seventeen)

I had children, now I have a problem, now the children can solve the problem. Tomorrow, God willing I cannot help myself, it is on the children I will depend. Today I chape them. Tomorrow God willing we struggle with life together.5 (forty-one-year-old mother of four)

And to recall women in Jean Rabel commenting on the importance of a husband,

He gives me money for the children, that is what makes me prefer having him around.6 (twenty-seven year-old mother of five)

What I am telling you is when you are young, you need a husband. What I mean is, if you haven’t had children yet. So you can make a child.7 (forty-two-year-old mother of three)

If a person marries, why does she marry? She does not marry to be a big shot or anything like that. It is so she can have children… Why does a person want children? It is to help…to go to the water…to go get wood.8 (forty-year-old mother of five)

He has to come sit there and help me chape the children.9 (forty-year-old mother of four)

And once the children are there,

What makes me say I can live without a man? What I need to do to come up with a sack of food I can accomplish with my four children.10 (thirty-year-old mother of four).

If I have children, I don’t need my husband at all. Children, hey! hey! I would like to have ten children. I don’t need my husband.11 (forty-one-year-old mother of seven).

Why can I live without a man? I arrive at an age like this. All my affairs are in order. I don’t need my husband anymore.12 (fifty-six-year-old mother of eight)

If we accept the argument that children were considered critical to household production, that they were highly desired, that increased availability of money made successful pregnancies and child survival more likely—and women and their families more inclined to accept male consorts—then the question is how were women able to bear more children precisely when there were fewer men. How fertility increased during periods of high male absenteeism was precisely because of polygyny and unstable unions, types of conjugal unions common in the Caribbean and that Bongaarts and Potter (1983) and other researchers erroneously posited as lowering the “exposure to the risk of pregnancy,” thereby precipitating a drop in number of births (see Wood 1995 for a review of conflict surrounding this issue).

Polygyny, although never legal in the Caribbean, was long identified as part of an informal “standard” whereby married men could assume responsibility for additional common-law wives. In these “extramarital” unions, the women lived in separate homesteads or, in a form not recognized as a consummated union, remained in the homesteads of their parents (known in the anthropology of the Caribbean as a “visiting union”). The men performed as de facto husbands, providing support and fathering children. This nonlegal, or de facto, polygyny made it possible for a greater number of women to gain socially accepted sexual access to and financial support from the fewer available but more financially capable men, thereby overcoming imbalanced sex-ratios caused by male migration (for Haiti, see Herskovits 1937: 114 –15; Simpson 1942: 656; Murray 1977: 263; for Carriacou, see M. G. Smith 1961: 469; 1962: 117–22, 463–65, 1966: xviii; Hill 1977: 281; for the Commonwealth Caribbean, see Otterbein 1965; Marino 1970; Sutton and Makiesky‑Barrow 1970: 312–13: for Jamaica, see Clarke, 1966; for Trinidad, see Greenfield, 1966; for Providencia, see Wilson 1973: 79; for Belize, see Gonzalez 1969: 49; for St. John, see Olwig 1985: 125; for St. Vincents, see Gearing 1988: 219; for Montserrat, see Philpott 1973: 116, 119; for British Guyana, see R. T. Smith, 1988).

Greater numbers of births during times of male absenteeism were also made possible through a series of relationships, what can be called unstable union. Serial mating, or what is sometimes called serial monogamy (without the emphasis on legal marriage), was socially viable and acceptable in the Caribbean. Women often began childbearing while still living in the home of their parents (see Clarke 1966: 99; Blake 1961; Greenfield 1966; Freilich 1968: 52; Senior 1991); they waited to commit to matrimony until toward the end of their reproductive careers when they were in their thirties and forties (Massiah 1983: 14; Roberts, 1957: 206–7). The trend was manifest in the fact that up until the 1970s, 40 to 75 percent of all Caribbean children were born to unmarried women (Senior 1991: 82; Roberts, 1957: 202); and 50 percent of Caribbean women bore children by two or more partners over the course of their lives (Ebanks et al. 1974; Ebanks 1973; Roberts, 1957).

The extent to which it was in fact polygyny and serial mating that made increased birth rates in the Caribbean possible when fewer men were present is evident in the increasing incidence of illegitimate births during times of heavy male absenteeism, called a Caribbean “structural principle” by Hill (1977: 281; see also Otterbein 1965; M.G. Smith 1962: 117–22; Roberts 1957: 220). The birth histories of individual Caribbean women also demonstrated the relationship. Those women with the highest fertility levels were not, as expected in Bongaarts and Potter’s model, those who remained in stable union. Ebanks et al. (1974) in Barbados and Ebanks (1973) in Jamaica found that in contrast to conventional demographic theory, the number of children a woman gave birth to in her lifetime increased with the number of partnerships she had. This was the case even when the researchers controlled for present age, age at entry into first union, age at first pregnancy, time spent within sexual union, time spent outside of union, type of union, and contraceptive use (see also Wilson 1961, for a similar finding in Providencia, and Marino, 1970: 166, who compared age cohorts of women from eight different islands).

Conclusion

I have tried to show how Caribbean family patterns were a response to basic economic challenges that confronted impoverished people living in the region. The costs of households and the need for children to make them productive set up conditions that would give way to the familial patterns found in the Caribbean. Both women, parents, and, arguably, men subscribed in principle to elite values of marriage and monogamy. Indeed, in the Caribbean, female participation in the salaried labor force has been correlated with increased marriage rates and lower rates of illegitimacy, i.e., when women have a dependable source of extrahousehold income they marry (Abraham 1993). But it was not historically so easy. Low income Caribbean parents, especially mothers, wanted children and grandchildren, indeed needed them to make the household productive. But they wanted—and arguably needed—their daughter to father them with men who could provide income to at least help get the children through the early period of dependency, that critical zero to five years stage before children became contributing members of the household. Moreover, as women advanced in their reproductive careers, they depended on men to underwrite the costs of establishing a new productive homestead and the beginning of their marketing careers.

Thus, a particular configuration of a sexual moral economy emerged. Mothers tightly controlled daughters. They instilled them with fear of contraception and abortion, kept them in the dark about the mechanics of pregnancy, and monitored their sexual activities. On the other side of the equation, sons were encouraged to be sexually aggressive and ridiculed for not conforming. A man was not a man if he did not have premarital and extramarital sex and his status depended heavily on the number of children he sired. Not warned by mothers, not protected against men with financial resources, daughters were left defenseless against pregnancy.

On the part of males, the scarcity of cash and salaried jobs made it difficult for them to find the means to meet the demands of women and their families and most importantly of all, to finance a household. The primary way men got the money was by migrating. Wage migration became a male determinant of parenthood in much of the Caribbean, a veritable rite of passage. If men wanted to fully participate in adult social life they often had to migrate. But it was emphatically not an issue of men simply seeking the means to meet financial demands attached to sex. And it is here that we come back once again to the other side of the issue, the side often ignored in the literature: the dependency of Caribbean men on women and children, seen earlier; for economic autonomy, dignity, and respect ultimately accrued to impoverished West Indian men only through the co-ownership of the most important means of production and mechanism for survival in the Caribbean, a household.

The frequent absences of men, the increased income of those who were present, and the increased income through remittances from fathers, brothers, sons, and lovers, in combination with pressure from elders and ignorance of the mechanisms of childbirth, meant that many women were more likely not to marry until later in life, to keep options open to them, and to begin or to intensify their childbearing career during times of high male wage migration—when men were scarcer but had greater resources—resulting in the counterintuitive phenomenon of fewer men, more babies. When men and women did marry it was to consolidate exclusive ownership, rights to production, and heredity for an already long established and productive household—especially important to a woman in lieu of the probability that her now financially mature husband might engage in extra-marital unions that result in the birth of “outside” children, i.e. polygyny.

Moreover, although it struck most Western observers as bizarre, the fewer-men-more-babies phenomenon may be much more widespread than the Caribbean. Ethnographers in Polynesia (Larson 1981), in Thailand (Kunstadter 1971), in New Guinea (Taufa et al.1990), and in rural Spain (Reher and Iriso-Napal 1989) all found statistically positive relationships between increased birth rates and male absenteeism brought about by wage migration. Researchers analyzing large samples of cross-country data for developing regions have similarly noted that migration delays the transition to lower fertility (Bilsborrow 1987; Bilsborrow and Winegarden 1985); Bongaarts himself noted that in sub-Saharan Africa—an area characterized by high male wage migration—fertility-inhibiting effects expected from migration did not come about, the reasons for which he could only speculate (Bongaarts et al. 1984: 511). Indeed, what perplexed Bongaarts is an old and apparently much forgotten idiosyncrasy that vexed earlier students of the demographic transition. Even Kingsley Davis (1963), the original formulator of the proximate and immediate determinants of fertility and one of the most important demographers of the 20th century, noted that emigration often offset fertility decline (see also Friedlander 1969; Mosher 1980; Moore 1945: 119; Hawley 1950, particularly chapter 9). But as with so many other demographic trends that did not fulfill the expectations of social scientists, this issue of migration offsetting fertility decline was ignored.

*****

Notes

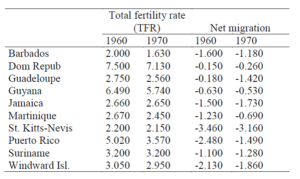

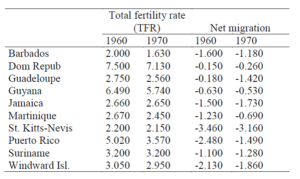

. The landmark study supporting that migration—and hence male absenteeism— disrupted fertility in Caribbean communities was carried out by McElroy and Albuquerque (1990) who tested data from ten countries in the Commonwealth Caribbean. Using a Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient, they measured the relationship between out-migration and fertility for the 1960–1965 and the 1965–1970 periods. Their results yielded correlation coefficients of -0.52 and -0.39 (McElroy and Albuuquerque 1990: 792), respectively. Neither of the tests were statistically significant at the 0.05 level, the data nevertheless seemed to indicate that out-migration correlates negatively with fertility decline in Caribbean sending countries—the higher the out-migration the lower the fertility rate. But, rather than demonstrating that male wage migration disrupts fertility, their data can be interpreted as demonstrating the opposite.

First, although their argument that emigration during the 1960s is “dominated by females” (McElroy and Albuquerque cite Marshal, 1985:52), temporary wage migration was clearly dominated by men. Looking at Marino’s sex ratio chart (in the main text) it can be seen that out of the ten Caribbean countries for which McElroy and Albuquerque provide data, men were in the minority in all but one; in most of the cases men were outnumbered by reproductive-age females three to two and in some cases there were almost twice as many reproductive-age females as men.

The most significant shortcoming in their argument has to do with attempting to identify the “independent influence of migration” that McElroy and Albuquerque claimed they had isolated (1990: 785). The researchers did not account for other variables affecting fertility, such as wage labor available to women. This neglect is understandable because, as the authors themselves point out, reliable cross-country socioeconomic data for the Caribbean is scarce (McElroy and Albuquerque 1990: 785–86). On the other hand, the failure to exercise socioeconomic controls damages the validity of their argument. And here is why:

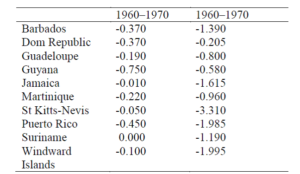

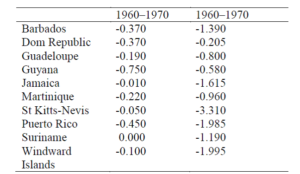

Like other areas of the world, the Caribbean during the 1960s was experiencing dramatic socioeconomic changes. Specifically, in the countries included in McElroy and Albuquerque’s sample, the percentage of the labor force engaged in agriculture declined by an average of 30 percent; the percentage of population living in urban areas increased by 24 percent; female enrollment in primary school increased by 44 percent; life expectancy increased by an average of 5.1 years; and in most instances, infant mortality declined precipitously—in Grenada, for example, infant mortality declined from 77.9 to 34 deaths per 1,000; all factors known to precipitate or at least be associated fertility transition (Caldwell 1982; Handwerker 1986). And indeed, congruent with changes in living standards and economic conditions, Caribbean Total Fertility Rates declined during this period by an average .351 births per women.

Table 1: Caribbean net migration by total fertility rate

Because of the dramatic changes in demographic, health, and socioeconomic conditions, the measurement of interest for McElroy and Albuquerque should not have been how much Caribbean out-migration correlated with fertility levels. The relationship that McElroy and Albuquerque should have measured is how much out-migration detracted from or sped Caribbean fertility decline, i.e., the average level of migration correlated with the change in fertility rates. When McElroy and Albuquerque’s data is used to plot the changes in TFR (1970 TFR minus 1960 TFR) against the rate of out-migration, a very different picture emerges than that proposed by the researchers.

The amount of reduction in fertility levels for individual Caribbean countries correlated with the average rate of migration for the 1960 to 1970 period indicates an association between small or absent fertility decline and high levels of out-migration (see table 18.2). A Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient yields a -.340 (without significance below the .05 level). In effect, the higher the migration the lower the fertility decline. When Puerto Rico is excluded from the data set, because it is an outlier and was experiencing large-scale economic and social intervention from the United States during this era, a Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient takes on the value of -.628 (with significance below the .05 level. Thus, rather than stimulating fertility decline, it could more easily be argued that migration offset fertility decline. Moreover, the studies provided by Marino (1970) and Brittain (1990, 1991a, 1991b) demonstrate that before the onset of rapid fertility decline in the region, there was a correspondence between male absenteeism and increased birth rates.

Table 2: Correlations in average change in total fertility rate by net migration

- The fewer men, more babies relationship was also evident in Jean Rabel. With the first coup d’etat (1991) that deposed democratically elected Jean Bertrand Aristide and the ensuing three years of international embargo, the migration of men conspicuously intensified. An unprecedented wave of mostly young males left the area headed for the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Suriname, Cuba, Panama, Honduras, Venezuela, Colombia, Mexico, the United States, and the nearby Bahamas. The migration was such that in 1997, Jean Rabel sex ratios for the twenty- to thirty-four-year age varied from eighty-five to ninety-two males for every one hundred females. Most of these missing men had left home in search of employment so they could remit income primarily to mothers, mothers of their children, wives, and girlfriends. Moreover, using clinic data from the Bon Nouvel Mission (a clinic in Jean Rabel), and comparing that data for the periods before and after 1992 suggests that birth rates during this period markedly increased. Comparing the seven year time period (1985–1992) with the six year time period (1993–1999), there was a 20 percent decrease in contraceptive use from 6.9 percent to 5.5 percent; a two-year decline in mother’s age at first birth , from twenty-two to twenty years of age ( P < .05); and a 5.9 month decline in the average length of a woman’s first inter-birth interval, from 29.5 to 23.6 months (p > .05 but p < .10).

- “Lè li ka boukannen” (when he can barbeque) is an expression that derives from children digging up and cooking sweet potatoes, something young children, especially boys, often do, and it signifies a child’s ability to look after himself.

- O, pou ki yon moun fe ti moun? Ke vle di, ou fe ti moun nan. W-ap bat pou chape yo. . . . L-ap grandi yo. L-ap chape. Demen si dieu vle, si ou bezwen ti dlo li ka ba ou. Si ou bezwenn ti bout bwa li ka pote li pou ou. Ou bezwenn ni konn ed.

- Mwen fe ti moun, kounye-a m vin gen yon pwoblem, kounye-a ti moun ka redi pwoblem. Demen si dieu vle, m vin pa kapab, se sou kont ti moun m-ap vini. Kounye-a map chape yo. Demen si dieu vle yo ka bat ave-m.

- L-ap ba-m di goude pou ti moun, se sa k fe m ta reme sa

- Non. Lè yon moun jenn, bagay sa m-ap di, ou bezwenn yon mari, komsi m di, si ou poko enfante, ou ka enfante yon ti moun.

- Si yon moun marie, pou ki sa li marie? Li pa marie ni pou chef ni pou anyen. Se pou li ka fe dè ti moun. . . . En ben, pou kisa yon moun fe ti moun? Se pou li ka ed-o. . . al nan dlo-a . . . al nan bwa.

- M-ap swiv neg la, paskè m gentan gen pitit ave-li. Li pa ka abandone ni net. Fo-k li vin chita la pou ede-m chape ti moun yo

- En ben, ki fe-m ka viv san gason? Sa-m bezwenn m ka leve yon sak manje, se a kat ti moun um m ka rive.

- Si m gen ti moun m pa bezwenn mari-m menm. Ti moun, hoy, hoy. M ta reme dis pitit, m pa bezwenn mari.

- Pou ki rezon fe-m ka viv san gason. Ko-m rive nan laj konsa. Tout afe-m mache. M pa bezwenn mari-m anko.

Works Cited

AAA (AgroActionAllemande). 1998. Market Analysis of Jean Rabel Unpublished report by Thomas Hartmanship. Bonn: Germany.

Abraham, Eva. 1993. Caught in the shift: The impact of industrialization on the female-headed households in Curacao, Netherlands Antilles. In Where did all the men go?, ed. J. Mencher and A. Okongwu. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Adams, Lorraine. 1994. North didn’t relay drug tips. Washington Post, Oct. 22: 1.

Allman, James. 1980. Sexual union in rural Haiti. International Journal of Sociology of the Family 10:15–39.

———. 1982a. Haitian migration: 30 years assessed. Migration Today (1):7–12.

———. 1982b. Fertility and family planning in Haiti. Studies in Family Planning 13(8/9):237–45.

Allman, James, and J. May. 1979. Fertility, mortality, migration and family planning in Haiti. Population Studies 33(3):505–21.

Alphonse, Henri. 1996. Haiti-agriculture: last battle of the coffee planters. Amsterdam: InterPress Third World News Agency (IPS).

Ashcraft, Norman. 1968. Some aspects of domestic organization in British Honduras. In The family in the Caribbean: Proceedings of the first Conference on the Family in the Caribbean, St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, March 21–23, 63–73. Rio Piedras, P.R.: Institute of Caribbean Studies, University of Puerto Rico.

Augelli, John P. 1953. Patterns and problems of land tenure in the Lesser Antilles, B.W.I. Economic Geography 29(4):362–67.

Aymer, Paula L. 1997. Coming from the Caribbean: Knowledge production and cultural transformations. In Uprooted women: Migrant domestics in the Caribbean. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Baber, Willie L. 1982. Social change and the peasant community: Horowitz’s Morne Peasant reinterpreted. Ethnology 21(3):227–41.

Balch, Emily Greene. 1927. Occupied Haiti. New York: The Writers Publishing Company.

Barickman, B. J.1994. “A bit of land, which they call roca:” Slave provision grounds in the Bahian Reconcavo, 1780–1860. The Hispanic American Historical Review 74(4):649–87.

Barrow, Christine. 1986. Finding the support: A study of strategies for survival. Social and Economic Studies 35(2):131–77.

———, ed. 1997. Caribbean portraits: Essays on gender ideologies and identities. Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers.

Bastien, Remy. 1961. Haitian rural family organization. Social and Economic Studies 10(4):478–510.

Bazile, Robert. 1967. Demographic statistics in Haiti. In The Haitian potential. New York: Teachers College Press.

Becker, Gary. 1960. An economic analysis of fertility. In Demographic and economic change in developed countries: A conference of the universities—National Bureau Committee for Economic Research, 209–31. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Beckett, Greg. 2004. Master of the wood: Moral authority and political imaginaries in Haiti. PoLAR: The Political and Legal Anthropology Review 27(2):1–19.

Beckford, George. 1972. Persistent poverty: Underdevelopment in plantation economies of the third world. New York: Oxford University Press.

Berggren, Gretchen, Nirmala Murthy, and Stephen J Williams. 1974. Rural Haitian women: An analysis of fertility rates. Social Biology 21:368–78.

Berleant-Schiller, Riva. 1978. The failure of agricultural development in post-emancipation Barbuda: A study of social and economic continuity in a West Indian community. In Boletin de Estudiois Latinoamericanos y del Caribe, Dec 25:21–36.

Bernstein, Dennis, and Howard Levine. 1993. The CIA’s Haitian connection. San Francisco Bay Guardian, November 3.

Bethel, Nicolette. 1993. Bahamian kinship and the power of women. Master’s thesis, Corpus Christi College.

BiblioMundo. 2006. Haiti La Diaspora. At www.bibliomonde.net/donnee/haiti-diaspora-293.html, accessed April 19.

Bilsborrow, Richard E. 1987. Population pressures and agricultural development: A conceptual framework and recent evidence. World Development 15(2):183–203.

Bilsborrow, Richard E., and C. R. Winegarden. 1985. Landholding, rural fertility and internal migration in developing countries: Econometric evidence from cross-national as data. Pakistan Development Review 24(2):125–49.

Blackwood, Evelyn. 2005. Wedding bell blues: Marriage, missing men, and matrifocal follies. American Ethnologist 32(1):3–19.

Blake, Judith. 1954. Family instability and reproductive behavior in Jamaica. Milbank Memorial Annual Conference:26–61.

———. 1961. Family structure in Jamaica; the social context of reproduction. In collaboration with J. Mayone Stycos and Kingsley Davis. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

Blumberg, Rae Lesser. 1993. Where did all the men go? Boulder, CO: Westview.

Blurton-Jones, Nichol. 1993. The lives of hunter and gatherer children: Effects of parental behavior and parental reproductive strategy. In Juvenile primates, ed. Michael E. Pereira and Lynn A. Fairbanks, 309–26. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bock, John, and Sara E. Johnson. 2004. Subsistence ecology and play among the Okavanga Delta people of Botswana. Human Nature 15(1):63–82.

Bongaarts John. 1978. A framework for analyzing the proximate determinants of fertility. Population and Development Review 4(1):105–32.

———. 1982. The fertility-inhibiting effects of the intermediate fertility variables. Studies In Family Planning 13(6/7):179–89.

———. 1987. The proximate determinants of exceptionally high fertility. Population and Development Review 13(1):133–39.

Bongaarts, John, and Robert C. Potter. 1983. Fertility, biology, and behavior: An analysis of the proximate determinants. New York: Academic Press.

Bongaarts, John, O. Frank, and R. Lesthaeghe. 1984. The proximate determinants of fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review 10(3):511–37.

Boserup, Ester 1965. The condition of agricultural growth: The economics of agrarian change under population pressure. Chicago: Aldine.

Bouwkamp, John C. 1985. Sweet potato products: A natural resource for the tropics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Branche, C. 2002. Ambivalence, sexuality, and violence in the construction of Caribbean masculinity: dangers for boys in Jamaica. In Children’s rights: Caribbean realities, ed. C. Barrow. Jamaica: Ian Randle.

Brereton, Bridget. 1989. Society and culture in the Caribbean. In The modern Caribbean, ed. Franklin W. Knight and Colin A. Palmer. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 2007. www.answers.com/topic/french-guiana

?cat=travel.

Brittain, Ann W. 1990. Migration and the demographic transition: A West Indian example. Social and Economic Studies 39(3):39–64.

———. 1991a. Anticipated child loss to migration and sustained high fertility in an East Caribbean population. Social Biology 38(1-2):94-112

———. 1991b. Can women remember how many children they have borne? Data from the east Caribbean. Social Biology 38(3-4):319–32.

Brockerhoff, Martin, and Xiushi Yang. 1994. Impact of migration on fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Biology 41(1-2):19–43.

Brodber, E. 1974. Abandonment of children in Jamaica. Kingston, Jamaica: Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of West Indies.

———. 1986. African-Jamaican women at the turn of the century. Social and Economic Studies 45:23–60.

Brown, Janet. 2002. Gender and family in the Caribbean. At www.kit.nl/exchange/

html/2002-4_gender_and_family_in_th.asp.

———. 2007. Fatherhood in the Caribbean: Examples of support for men’s work in relation to family life. In Gender equality and men: Learning from practice, ed. Sandy Ruxton, 113–30. At www.oxfam.org.uk/what_we_do/resources/downloads/gem-13.pdf.

Buschkens, W. F. L. 1974. The family system of the Paramaribo Creoles. Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff.

Cadet, Jean-Robert. 1998. Restavec: From Haitian slave child to middle-class American. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Cain, Mead. 1977. The economic activities of children in a village in Bangladesh. Population and Development Review 3:201–7.

Caldwell, John C. 1976. Toward a restatement of demographic transition theory. Population and Development Review 2(3/4):321–66.

———. 1982. Theory of fertility decline. San Francisco: Academic Press.

Caldwell, John C., and Pat Caldwell. 1987. The cultural context of high fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review 13(3): 409–37.

Camus, Michel-Christian. 1993. Filibuste et pouvoir royal. Revue de la Société Haitienne d’Histoire et de Geographie 49(175).

CARE. 1996. A baseline study of livelihood security in northwest Haiti. Tucson, AZ: The Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona.

———. 1997. An update of household livelihood security in Northwest Haiti monitoring targeting impact evaluation/Unit December. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: CARE International.

Castor, Suzy. 1971. La occupation norteamericana de Haiti y sus consequencias. Mexico: Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

CELADE (Centro Latinoamericano y Caribeño de Demografía). 2000. América Latina: Proyecciones de población urbano–rural population 1970–2025 [Latin America: Projection Of Urban–Rural Population 1970–2025]. Santiago, Chile: Centro Latinoamericano y Caribeño de Demografía (CELADE / CEPAL). Available at www.eclac.cl/Celade/publica/bol63/BD63.html, accessed April 30, 2006.

Census Records. n.d. Archives de France, Section D’outre-Mer, Aix-En-Provence, G1/509.

Charbit, Yves. 1984. WFS Scientific Reports no. 65. Voorburg, Netherlands: International Statistical Institute.

Chayanov, A. V. 1925. Peasant farm organization. Moscow: The Co-operative Publishing House.

Chevalier, George-Ary. 1938. Etude sur la colonisation francaise en Haiti: Origines et developpement des propriétès Collette. Revue de la Société Haitienne d’Histoire et de Geographie 9(31).

———. 1939. Etude sur la colonisation Francaise a Saint-Domingue. Revue de la Société Haitienne d’Histoire et de Geographie 10(33).

———. 1940. Un colon de Saint-Domingue pendant la révolution. Pierre Collette, Planteur de Jean Rabel. Revue de la Société Haitienne d’Histoire et de Geographie 12(36).

Chevannes, B. 2002. Fatherhood in the African-Caribbean landscape: An exploration in meaning and context. In Children’s rights: Caribbean realities, ed. C. Barrow. Jamaica: Ian Randle.

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. U.S. & Haiti. Third World Traveler Z. At www.thirdworld

traveler.com/Haiti/US_Haiti_Chomsky.html, accessed February 3, 2007.

CIA. 2007. World Fact Book. At www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook, accessed April 15, 2006.

Clarke, E. 1966 (originally published in 1957). My mother who fathered me: A study of the family in three selected communities in Jamaica, 2nd ed. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Clement, Christopher. 1997. Returning Aristide: The contradictions in US foreign policy

in Haiti. Race and Class 39(2):21–36.

Clesca, Eddy. 1984. La domesticité juvénile est-elle une conséquence du sousdeveloppement ou le produit de la mentalité d’un peuple? In Colloque sur l’enfance en domesticité. Conference Report, Institut du Bien-Etre Social et de Recherche & UNICEF.

Coale, A. 1986. The decline of fertility in Europe since the eighteenth century as a chapter in demographic history. In The decline of fertility in Europe, ed. Coale and Watkins, 1–30. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cock, James H. 1985. Cassava: New potential for a neglected crop. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Cohen, Yehudi A. 1956. Structure and function: Family organization and socialization in a Jamaican community. American Anthropologist 58:664–87.

Cole, Johnnetta B. 1985. Africanisms in the Americas: A brief history of the concept. Anthropology and Humanism Quarterly 10(4):120–26.

Comhaire-Sylvain, Suzanne. 1958. Courtship, marriage and plasaj at Kenskoff, Haiti. Social and Economic Studies 7:210–33.

———. 1961. The household at Kenscoff, Haiti. Social and Economic Studies 10:192–222.

Comitas, Lambros. 1964. Occupational multiplicity in rural Jamaica. In Proceedings of the American Ethnological Society, ed. E. Garfield and E. Friedl, 41–50. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Corbett, Bob. n.d. Haiti: Miscellaneous topics. At www.webster.edu/~corbetre/Haiti/

misctopic/misctopic.htm, accessed April 6, 2006.

Coreil, Jeanine. 1980. Traditional and Western responses to an anthrax epidemic in rural Haiti. Medical Anthropology 4:79–105.

Coreil, Jeanine, Deborah L. Barnes-Josiah, Antoine Agustin, and Michel Cayemittes. 1996. Arrested pregnancy syndrome in Haiti: Findings from a national survey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, 10(3):424–36.

Courlander, Harold. 1960. The Hoe and the drum: Life and lore of the Haitian people. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cousins, W. M. 1935. Slave family life in the British colonies: 1800–1834. The Sociological Review 27:35–55.

Crahan, Margaret E., Franklin W. Wright, and Roger N. Buckley, eds. 1980. Africa and the Caribbean: The legacies of a link. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Crane, Julia G. 1971. Educated to migrate: The social organization of Saba. Assen, Netherlands: van Gorcum.

Cross, Gary. 2004. The cute and the cool: Wondrous innocence and modern American children’s culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crowley, Daniel J. 1957. Song and dance in St. Lucia. Ethnomusicology 9 (January):4–14.

Cumper, George E. 1961. Household and occupation in Barbados. Social and Economic Studies 10(1):386–419.

Dalton, George. 1974. How exactly are peasants “exploited”? American Anthropologist 76(3):553–61.

D’Amico-Samuels, Deborah. 1988. Review of Coping with poverty: Adaptive strategies in a Caribbean village by Hymie Rubenstein. American Ethnologist 15(4):785–86.

Das Gupta, M. 1994. What motivates fertility decline? A case study from Punjab, India. In Understanding reproductive change: Kenya, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Costa Rica, ed. B. Egero, M. Hammarskjold, 101–33. Lund, Sweden: Lund University Press.

Davenport, William. 1961. The family system of Jamaica. Social and Economic Studies, 4(1):420–54.

Davis, Kingsley. 1963. The theory of change and response in modern demographic history. Population Index 29:345–66.

Davis, Kingsley, and Judith Blake. 1956. Social structure and fertility: An analytical framework. Economic Development and Cultural Change 4(4):211–35.

Deere, Carmen, Peggy Antrobus, Lynn Bolles, Edwin Melendez, Peter Phillips, Marcia Rivera, and Helen Safa. 1990. In The shadows of the sun: Caribbean development alternatives and U.S. policy. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Dehavenon, A. 1993. Where did all the men go? An etic model for the cross-cultural study of the causes of matrifocality. In Where did all the men go?, ed. J. Mencher and A. Okongwu. Boulder, CO: Westview.

DeLancey, V. 1990. Socioeconomic consequences of high fertility for the family. In Population growth and reproduction in sub Saharan Africa: Technical analyses of fertility and its consequences, ed. G. T. F. Acsadi, G. J. Acsadi, and R. A. Bulatao, 115–30. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Denton, E. Hazel. 1979. Economic determinants of fertility in Jamaica. Population Studies 33(2):295–305.

Divinski, Randy, Rachel Hecksher, and Jonathan Woodbridge, eds. 1998. Haitian women: Life on the front lines. London: PBI (Peace Brigades International). At www.

peacebrigades.org/bulletin.html.

Doggett, Hugh. 1988. Sorghum. New York: John Wiley.

Dorélien, Renand. 1990 [1984]. Résumé de la communication sur « interprétation des données statistiques relatives à l’enfance en domesticité recueillies à partir des résultats d’un échantillon tiré du recensement de 1982.» Atelier de travail sur l’enfance en domesticité. Port-au-Prince, 5, 6 et 7 décembre 1990. Port-au-Prince: Institut du Bien-Etre Social et de Recherche & IHSI.

Doyle, Kate. 1994. Hollow diplomacy in Haiti. World Policy Journal 11(1):50–58.

Driver, Tom. 1996. USAID and Wages (contribution to a dialog on Bob Corbett’s Haiti list). At www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/43a/index-d.html, accessed September 3, 2008.

Duany, Jorge. 1984. Popular music in Puerto Rico: Toward an anthropology of “Salsa.” Latin American Music Review 5(2):186–216.

Durant-Gonzalez, Victoria. 1976. Role and status of rural Jamaican women: Higglering and mothering. Master’s thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Eaton, Joseph W., and Albert J. Mayer. 1953. The social biology of very high fertility among the Hutterites: The demography of a unique population. Human Biology, 25:206–64.

Ebanks, G. Edward. 1973. Fertility, union status, and partners. International Journal of Sociology and the Family 3(1):48–60.

Ebanks, G. Edward, P. M. George, and Charles E. Nobbe. 1974. Fertility and number of partnerships in Barbados. Population Studies 28(3): 449–61.

Ebanks, G. Edward and Charles E. Nobbe. 1975. Emigration and fertility decline: The case of Barbados. Demography 12(3):431–45.

EMMUS-I. 1994/1995. Enquete Mortalite, Morbidite et Utilisation des Services (EMMUS-I). eds. Michel Cayemittes, Antonio Rival, Bernard Barrere, Gerald Lerebours, Michaele Amedee Gedeon. Haiti, Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-II. 2000. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Florence Placide, Bernard Barrère, Soumaila Mariko, Blaise Sévère. Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-III. 2005/2006. Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD : Macro International.

FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United States). 2006. The state of food and agriculture. Prepared by a team from the Agriculture and Economic Development Analysis Division. F.L. Zegarra, team leader. At www.fao.org/docrep/

v6800e/V6800E02.htm, accessed May 2, 2006.

Fass, Simon. l988. Political economy in Haiti: The drama of survival. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Feight, C. B., T. S. Johnson, B. J. Martin, K. E. Sparkes, and W. W. Wagner. 1978. Secondary amenorrhea in athletes. Lancet 2:1145–46.

Foner, Nancy, and R. Napoli. 1978. Jamaican and Black American migrant farm-workers: A comparative analysis. Social Problems 25:491–503.

Foster, George M. 1953. Cofradia and compadrazgo in Spain and Spanish America. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 9:1–28.

———. 1969. Compadrazgo and social networks in Tzintzuntzan. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 25:261–78.

Francis, Donette A. 2004. Silences too horrific to disturb: Writing sexual histories in Edwidge Danticat’s Breath, eyes, memory. Research in African Literatures 35(2):75–90.

Frazier, E. Franklin. 1939. The Negro family in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 1957. Black bourgeoisie: The rise of a new middle class. Glencoe: The Free Press.

Freeman, Ronald. 1962. The sociology of human fertility: A trend report and bibliography. Current Sociology 11(2):35–68.

Freilich, Morris. 1967. Review of The Andros Islanders: A study of family organization in the Bahamas, by Keith Otterbein. American Anthropologist 69(2):239.

———. 1968. Sex, secrets and systems. In The family in the Caribbean: Proceedings of the first conference on the family in the Caribbean, St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, March 21–23, 47–62. Rio Piedras, P.R.: Institute of Caribbean Studies, University of Puerto Rico.

Friedlander, Dov. 1969. Demographic responses and population change. Demography 6(4):359–81.

Frisch, R. E. 1978. Population, food intake and fertility. Science 199(4324):22–30.

Frisch, R. E., and J. W. McArthur. 1974. Menstrual cycles: Fatness as a determinant of minimum weight for height necessary for their maintenance or onset. Science 185:949–51.

Frisch, R. E., R. Revelle, and S. Cook. 1971. Height, weight and age at menarche and the “critical weight” hypothesis. Science 194: 1148.

Frucht, Richard. 1968. Emigration, remittances, and social change: Aspects of the social field of Nevis, West Indies. Anthropologica 10(2):193–208.

———. 1971. Black society in the New World. New York: Random House.

Fuller, Anne. 2005. Challenging violence: Haitian women unite women’s rights and human rights special bulletin on women and war. At acas.prairienet.org. accessed October 19, 2006. Originally published in the Spring/Summer 1999 by the Association of Concerned Africa Scholars.

Fund for Peace and Foreign Policy. 2007. The failed states index. Foreign Policy. At www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=3865.

Fuson, Robert H. 1987. The log of Christopher Columbus. Trans. by Robert H Fuson. Camden, ME: International Marine.

Gambrell, Alice. 1997. Women, intellectuals, modernism, and difference: Transatlantic culture 1919–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, Richard, and Aaron M. Podolefsky. 1977. Some further considerations on West Indian conjugal patterns. Ethnology 16(3): 299–308.

Gaspar, Barry. 1991. Antigua slaves and their struggle to survive. In Seeds of change, ed. H. Viola and C. Margolis, 130–37. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Gearing, Margaret Jean. l988. The reproduction of labor in a migration society: Gender, kinship, and household in St. Vincent, West Indies. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Geggus, David Patrick. 1982. Slavery, war, and revolution: The British occupation of Saint Domingue 1793–1798. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Georges, Josiane. 2004. Trade and the disappearance of Haitian rice. Ted Case Studies Number 725. At www.american.edu/TED/Haitirice.htm, accessed April 4, 2006.

González, Nancie L. 1969 [1958]. Black Carib household structure: A study of migration and modernization. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

———. 1970. Toward a definition of matrifocality. Afro-American anthropology: Contemporary perspectives, ed. Norman E. Whitten and John F. Szwed. New York: The Free Press.

———. 1979. La estructura del grupo familiar entre los Caribes Negros Guatemala, Ministry of Education, 1st ed.

———. 1984. Rethinking the consanguineal household and matrifocality. Ethnology 23(1):1–15.

Graham S. 1985. Running and menstrual dysfunction: Recent medical discoveries provide new insight into the human division of labor by sex. American Anthropologist 87:878–992.

Green, Howard. 1979. Basin migration and dollar flows. Caribbean basin economic survey 5(2):12–15.

Green, William A. 1977. Caribbean historiography, 1600–1900: The recent tide. Journal of Interdisciplinary 7(3): 509–30.

Greene, Margaret E. and Ann E. Biddlecom. 2000. Absent and problematic men: Demographic accounts of male reproductive roles. Population and Development Review 26(1):81–115.

Greenfield, Gerald Michael. 1994. Latin American urbanization: Historical profiles of major cities. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Greenfield, Sidney M. 1961. Socio-economic factors and family form: A Barbadian case study. Social and Economic Studies 10(1):72–85.

———. 1966. English rustics in black skin. New Haven: College University.

Griffith, David C. 1985. Women remittances and reproduction. American Ethnologist 12(4):676–90.

Grossman, Lawrence S. 1997. Soil conservation, political ecology, and technological change on St. Vincent. Geographical Review 87(3):353–74.

Guengant, Jean-Pierre. 1985. Caribbean population dynamics: emigration and fertility challenges. Conference of Caribbean parliamentarians, Heywoods, Barbados.

Hallward, Peter. 2004. Option zero In Haiti. New Left Review 27. At newleftreview.org/A2507.

Handwerker, W. Penn. 1983. The first demographic transition: An analysis of subsistence choices and reproductive consequences. American Anthropologist 85:5–27.

———. 1986. The modern demographic transition. American Anthropologist 88:400–17.

———. 1989. Women’s power and social revolution: Fertility transition in the West Indies. Newbury Park: Sage.

———. 1993. Empowerment and fertility transition on Antigua, WI: Education, employment, and the moral economy of childbearing. Human Organization 52(1):41–52.

Harner, Michael J. 1970. Population pressure and the social evolution of agriculturalists. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 26: 67–86.

Harris, Marvin. 1968. The rise of anthropological theory. New York: Harper & Row.

———. 1979. Cultural materialism: The struggle for a science of culture. New York: Random House.

Harris, Marvin, and Eric B. Ross. 1987. Death, sex, and fertility. New York: Columbia University Press.

Harrison, Lawrence E. 1991. The cultural roots of Haitian underdevelopment. In Small country development and international labor flows, ed. Anthony P. Maingot. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Hawley, A.1950. Human ecology. New York: Ronald.

Heath, B. J. 1988. Afro-Caribbean ware: A study of ethnicity on St. Eustatius. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Henriques, Fernando. 1949. West Indian family organization. American Journal of Sociology 55(1):30–37.

Henshall, Janet D. 1966. The demographic factor in the structure of agriculture in Barbados. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38:183–95.

Herskovits, Melville J. 1925. The Negro’s Americanism. In The New Negro, ed. Alain Locke. New York: Albert and Charles Boni.

———. 1937. Life in a Haitian valley. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hill, Donald R. 1977. The impact of migration on the metropolitan and folk society of Carriacou, Grenada 54. Part 2, Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. New York: AMNH.

Ho, Christine G. T. 1999. Caribbean transnationalism as a gendered process. Latin American Perspectives 26(5):34–54.

Hobart, Mark, ed. 1993. An anthropological critique of ignorance: The growth of ignorance. New York: Routledge.

Horowitz, M. 1959. Morne-Paysan: Peasant village in Martinique. Dissertation, Columbia University.

———. 1967. Morne-Paysan, peasant village in Martinique. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Hostetler, John A. 1974. Hutterite society. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Howell, Nancy. 1979. Demography of the Dobe !Kung. New York: Academic.

HSKI (Haitian Street Kids Inc). 2007. Family circle boys home: The solution. At

quicksitemaker.com/members/immunenation/index.html.

Hugo G. 1997. Intergenerational wealth flows and the elderly in Indonesia. In The continuing demographic transition, ed. G. W. Jones, R. M. Douglas, J. C. Caldwell, R. M. D’Souza, 111–33. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ibberson, Dora. 1956. Illegitimacy and the birth rate. Social and Economic Studies 5:93–99.

Iverson, Shepherd. 1992. Evolutionary demographic transition theory: comparative causes of prehistoric, historic and modern demographic transitions. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Jackson, J. 1982. Stresses affecting women and their families. In Women in the Caribbean project, ed. J. Massiah, 28–61. Cave Hill, Barbados: Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of the West Indies.

Johnson, Allen W., and Timothy Earle. 1987. The evolution of human societies. California: Stanford University Press.

Joy, Elizabeth. 1997. Team management of the Female Athlete Triad. Round Table 25(3):95.

Keen, F. G. B. 1978. Ecological relationships in a Hmong (Meo) economy. In Farmers in the forest: Economic development and marginal agriculture in Northern Thailand, ed. Peter Kunstadter, E. C. Champan, S. Sakhasi, 210–21. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Kerr, Madeline 1952. Personality and conflict in Jamaica. Liverpool: University Press.

Kundstadter, Peter. 1963. A survey of the consanguine or matrifocal family. American Anthropologist 65:56–66.

———, ed. 1967. Southeast Asian tribes, minorities, and nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

———. 1971. Natality, mortality and migration of upland and lowland populations in northwestern Thailand. In Culture and population: A collection of current studies, ed. Stephen Polgar, 46–60. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman.

———. 1983. Cultural ideals, socioeconomic change, and household composition: Karen Lua’, Hmong and Thai in Northwestern Thailand. In Households: Comparative and historical studies of the domestic group, ed. Robert McC. Netting, Richard R. Wilk, and Eric J. Arnould, 299–329. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———. 1993. Man in the mangroves: The socio-economic situation of human settlements in mangrove forests. The United Nations University. Tokyo, Japan.

———. 2002. Human population dynamics: Cross-disciplinary perspectives. Helen Macbeth and Paul Collinson, eds. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2004. Hmong marriage patterns in Thailand in relation to social change. In Hmong/Miao in Asia, ed. N. Tapp, J. Michaud, C. Culas, and G. Y. Lee. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm.

Lagro, Monique. 1990. The hucksters of Dominica. Port of Spain: United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Lagro, Monique and Donna Plotkin. 1990. The agricultural traders of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada, Dominica and St. Lucia. New York: United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Laguerre, Michel. 1979. Études sur le vodou Haïtien: Bibliographie analytique. Fonds St-Jacques: Centre de recherches Caribes.

Lancy, David. 2007. Accounting for variability in mother-child play. American Anthropologist 109(2):273–84.

Larsen Ula, and James W. Vaupel. 1993. Hutterite fecundability by age and parity strategies for fertility modeling of event histories. Demography 30(1):22.

Larson, Eric H. 1981. The effects of plantation economy on a Polynesian population. In And the poor get children, ed. Karen L. Michaelson, 39–49. New York: Monthly Review.

Lazarus-Black, Mindie. 2001. Interrogating the phenomenon of denial: Contesting paternity in Caribbean magistrates’ courts. Political and Legal Anthropology Review 24(1):13–37.

Lee, B. S. and S. C. Farber. 1984. The influence of rapid rural-urban migration on Korean national fertility levels. Journal of Development Economics 17:47–71.

Lee, R. 1996. A cross-cultural perspective on intergenerational transfers and the economic life cycle. In Seminar on intergenerational economic relations and demographic change: Papers, 1–25. Liege, Belgium: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population [IUSSP], Committee on Economic Demography.

Lee, Y. J., W. L. Parish, and R. J. Willis.1994. Sons, daughters, and intergenerational support in Taiwan. American Journal of Sociology 99:1010–41.

Lenaghan, Tom. 2005. Haitian Bleu: A rare taste of success for Haiti’s coffee growers. Development Alternatives Inc. At www.dai.com/pdf/developments/HaitianBleu-DAIdeasDec05.pdf, accessed April 20, 2006.

Leo-Rhynie, E. A. 1997. Class, race, and gender issues in child rearing in the Caribbean. In Caribbean families: Diversity among ethnic groups, ed. J. L. Rooparine & J. Brown, 25–56. Greenwich, CT: Ablex.

Lewis, David Levering. 1981. When Harlem was in vogue. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Lewis, Linden. 2003. Gender tension and change in the contemporary Caribbean. From expert group meeting on “The role of men and boys in achieving gender equality.” DAW in collaboration with ILO and UNAIDS, 21–24 October 2003 Brasilia, Brazil.

Leyburn, James G. 1966 [1941]. The Haitian people. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Liebenstein, H. M. 1957. Economic backwardness and economic growth. New York: Wiley.

Lillard, L. A., and R. J. Willis. 1997. Motives for intergenerational transfers: Evidence from Malaysia. Demography 34:115–34.

Locher, Uli. 1975. The market system of Port-au-Prince. In Working papers in Haitian society and culture, ed. Sidney W. Mintz. New Haven, CT: Antilles Research Program, Yale University.

Locke, Alain. 1925. Foreword to The New Negro, an interpretation. New York: Albert and Charles Boni.

Lowenthal, David. 1957. The population of Barbados. Journal of Economic and Social Studies 6:471.

———. 1963. Occupational multiplicity in rural Jamaica. In Symposium on community studies in anthropology, ed. V. Garfield and E. Friedl. Proceedings of the American Ethnological Society. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Lowenthal, David, and Lambros Comitas. 1962. Emigration and depopulation: Some neglected aspects of population geography. Geographical Review 52(2):195–210.

Lowenthal, Ira. 1987. Marriage is 20, children are 21: The cultural construction of conjugality in rural Haiti. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University.

———. 1984. Labor, sexuality and the conjugal contract. In Haiti: Today and tomorrow, ed. Charles R. Foster and Albert Valman. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Lundahl, Mats. 1983. The Haitian economy: Man, land, and markets. New York: St. Martin’s.

Mackenzie, Charles. 1830 [1971]. Notes on Haiti, made during a residence in that republic, Vol 1. London: Frank Cass.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 1973. The myth of population control: Family caste and class in an Indian village. New York: Monthly Review Press.

———. 1981. The ideology of population control. In And the poor get children, ed. Karen L. Michaelson, 39–49. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Mann, Jim. 1993. CIA’s aid plan would have undercut Aristide in ’87–88. Los Angeles Times, October 31.

Mantz, Jeffrey W. 2003. Lost in the fire, gained in the ash: Moral economies of exchange in Dominica. Dissertation, University of Chicago.

———. 2007. How a huckster becomes a custodian of market morality: Traditions of flexibility in exchange in Dominica. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 14:19–38.

Marino, Anthony. 1970. Family, fertility, and sex ratios in the British Caribbean. Population Studies 24(2):159–72.

Marshall, Dawn I. 1985. International migration as circulation: Haitian movement to the Bahamas. In Circulation in third world countries, ed. R. Mansell Prothero and Murray Chapman, 226–40. Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Massiah, Joycelin. 1982. Women who head households. In Women and the family, ed. J. Massiah, 62–130. Cave Hill, Barbados: Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of the West Indies.

———. 1983. Women as heads of households in the Caribbean: Family structure and feminine status. United Kingdom: UNESCO.

Maternowska, Catherine. 1996. Coups d’etat and contraceptives: A political economy analysis of family planning in Haiti. Dissertation, Columbia University.

Matthews, Dom Basil. 1953. Crisis of the West Indian family. Caribbean Affairs Series. Port of Spain, Trinidad: University of the West Indies.

Maynard-Tucker, G. 1996. Unions, fertility, and the quest for survival. Social Science & Medicine 43(9):1379–87.

McElroy, Jerome, and Klaus Albuquerque. 1988. The impact of migration on mortality and fertility in St. Kitts-Nevis and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Caribbean Geography 2(3):173–94.

———. 1990. Migration, natality and fertility: Some Caribbean evidence. International Review 24(4):783–802.

McGowan, Lisa A. 1997. Democracy undermined, economic justice denied: Structural adjustment and the aid juggernaut in Haiti. Washington, DC: Development Group for Alternative Policies.

McPherson, Matthew and Timothy Schwartz. 2001. The Defeminization of the Dominican Hinterlands: Conservation Implications for the Cordillera Central. The

Nature Conservancy: Arlington, Virginia.

Mencher, Joan P., and Anne Okongwu, eds. 1993. Where did all the men go? Female-headed, female-supported households in cross-cultural perspective. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Metraux, Rhoda. 1951. Kith and kin: a study of Creole social structure in Marbial, Haiti. Dissertation, Columbia University.

Midgett, D. K. 1977. West Indian migration and adaptation in St. Lucia and London. Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Millspaugh, Arthur C. 1931. Haiti under American control: 1915–1931. Boston: World Peace Foundation.

Mintz, Sidney. 1955. The Jamaican internal marketing pattern: some notes and hypothesis. Social and Economic Studies 4(1):95–103.

———. 1971. Men, women and trade. Comparative Studies in Society and History. 13:247–69.

———. 1974. Caribbean transformations. Chicago: Aldine.

———. 1981. Economic role and cultural tradition. In The black woman cross-culturally, ed. Filomina Chioma Steady, 513–34. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman.

———. 1985. From plantations to peasantries in the Caribbean. In Caribbean contours, ed. Sidney W. Mintz and Sally Price, 127–53. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mintz, Sidney, and Eric R. Wolf. 1950. An analysis of ritual co-parenthood (compadrazgo). The Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 6(4):341–65.

Modiano, Nancy. 1973. Indian education in the Chiapa highlands. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Mohammed, Patricia. 1986. The Caribbean family revisited. In Gender in Caribbean development, ed. Patricia Mohammed and Catherine Shepherd, 170–82. Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies.

Montague, Ludwell Lee. 1966. Haiti and the United States: 1714–1938. New York: Russel and Russel.

Moore W. E. 1945. Economic demography of Eastern Europe. Geneva, Switzerland: League of Nations.

Moral, Paul. 1961. Le Paysan Haitien. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose.

Moreau, St. Mery. 1797. Description de la partie Francaise de Saint-Domingue. Paris: Societe de l’Histoire de Colonies Francaises.

Mosher, William D. 1980. The theory of change and response: An application to Puerto Rico, 1940 to 1970. Population Studies 34(1):45–48.

Munroe, Ruth H., Robert L. Munroe, and Harold S. Shimmin. 1984. Children’s work in four cultures: determinants and consequences. American Anthropologist 86:369–79.

Murphy, Martin F. 1986. Historical and contemporary labor utilization practices in sugar industries of the Dominican Republic. Dissertation, Columbia University.

Murray Gerald F. 1972. The economic context of fertility patterns in a rural Haitian community. Report submitted to the International Institute for the Study of Human Reproduction. New York: Columbia University.

———. 1976. Women in perdition: Fertility control in Haiti. In Culture natality and family planning, ed. John Marshall and Steven Polgar, 59–79. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center.

———. 1977. The evolution of Haitian peasant land tenure: Agrarian adaptation to population growth. Dissertation, Columbia University.

———. 1991. The phantom child in Haitian voodoo: A folk-religious model of uterine life. In African creative expression of the divine, ed. Kortright Davis, Elias Farajaje-Jones, and Iris Eaton. Washington DC: Howard University School of Divinity.

Murray, Gerald, Matthew McPherson, and Timothy T. Schwartz. 1998. Fading frontier: An anthropological analysis of social and economic relations on the Dominican and Haitian Border. Report for USAID (Dom Repub).

Murthy, D. 1973. Loss of potential fertility due to unstable unions in Haiti. Unpublished manuscript, Harvard School of Public Health.

Nag, Moni. 1971. The influence of conjugal behavior, migration and contraception on natality in Barbados. In Culture and population: A collection of current studies, ed. Stephen Polgar, 105–23. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman.

Nag, Moni, Benjamin N. F. White, and R. Creighton Peet. 1978. An anthropological approach to the study of the economic value of children in Java and Nepal. Current Anthropology 19:293–306.

Naval, G. 1995. Evaluation of the crisis program of the catholic relief services in Haiti. Final report. Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Nene, Y. L., Susan D. Hall, and V. K. Sheila, eds. 1990. The pigeonpea. Andhra Pradesh, India: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics.

Newsom, Lee Ann. 1993. Native West Indian plant use. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Nicholls, David. 1974. Economic dependence and political autonomy: The Haitian experience. Occasional Paper Series No. 9. Montreal: McGill University, Center for Developing-Area Studies.

Nietschmann, Bernard. 1979. Ecological change, inflation, and migration in the far western Caribbean. Geographical Review 69(1):1–24.

Nonaka, K., T. Miura, and K. Peter. 1994. Recent fertility decline in Dariusleut Hutterites: An extension of Eaton and Mayer’s Hutterite fertility study. Human Biology 66(3):411–21.

Notestein, F. 1945. Population—the long view. In Food for the world, ed. T. W. Schultz, 36–57. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

NPR (National Public Radio). 2000. A restavec’s tale: Jean-Robert Cadet. February 18. At www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1070500.

———. 2007. Haiti’s dark secret: The restavecs: Servitude crosses the line between chores and child slavery. March 27, 2004 National Public Radio broadcast by Rachel Leventhal and Gigi Cohen, NPR Weekend Edition. At www.npr.org/

templates/story/story.php?storyId=1779562.

Nutini, Hugo G., and Betty Bell. 1980. Ritual kinship: The structure and historical development of the compadrazgo system in rural Tlaxcala. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Nzeza, Koko. 1988. Differential responses of maize, peanut, and sorghum to water stress. Master’s thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville.

N’zengou-Tayo M.J. 1998. “Fanm se poto mitan”: Haitian woman, the pillar of society [Fanm se poto mitan: la femme Haïtienne, pilier de la société]. Mona, Jamaica: Centre For Gender And Development Studies, University Of The West Indies.

Oloko, Beatrice Adenike. 1994. Children’s street work in urban Nigeria: Dilemma of modernizing tradition. In Cross-cultural roots of minority child development, ed. Patricia M. Greenfield and Robert R. Cocking, 197–224. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Olwig, Karen Fog. 1985. Cultural adaptation and resistance on St. John: Three centuries of Afro-Caribbean life. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Onwueme, I. C. 1978. Tropical tuber crops. New York: John Wiley.

Oprah. 2007. “Slavery” in Haiti and Ghana. From the show “A special report: The little boy Oprah couldn’t forget.” At www2.oprah.com/tows/slide/200702/20070209/

slide_20070209_284_115.jhtml.

Otterbein, Keith. 1963. The family organization of the Andros Islanders. Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh.

———. 1965. Caribbean family organization: A comparative analysis. American Anthropologist 67:66–79.

———. 1966. The Andros Islanders: A study of family organization in the Bahamas. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

———.1970. The evolution of war: A cross-cultural study. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press.

———.1986. The ultimate coercive sanction: A cross-cultural study of capital punishment. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press.

———. 1994. Feuding and warfare: Selected works of Keith F. Otterbein. New York and London: Routledge.

———. 2004. How war began. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Oxfam. 2005. Food aid or hidden dumping? Separating wheat from chaff. Briefing paper. At www.oxfam.org.uk/what_we_do/issues/trade/bp71_foodaid.htm, accessed May 1, 2006.

Palmer, Ransord W. 1974. A decade of West Indian migration to the United States, 1962–1972: An economic survey analysis. Social and Economic Studies 23(4):572–87.

Paul, Max. 1983. Black families in modern Bermuda. Göttingen, Germany: Edition Herodot.

Perusek, Glenn. 1984. Haitian emigration in the early twentieth century. International Migration Review l8:4–18.

Petras, Elizabeth McLean. 1988. Jamaican labor migration: White capital and black labor. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Philpott, Stuart. 1973. West Indian migration; the Montserrat case. London, Athlone Press.

PISANO. 1990. Rapport relatif aux resultats de l’enquete de donnes de base de Jean Rabel. Theis, W, S. Lund, and T. Janssen, eds. Hindenburgring, Germany: Juillet Istrupa Consulting.

Plummer, Gayle. 1985. Haitian migrants and backyard imperialism. Class and Race XXVI, 4:35–43.

Polgar, Steven. 1972. Population history and population policies from an anthropological perspective. Current Anthropology 13(2):203–11.

Pollock, Nancy. 1972. Women and the division of labor: A Jamaican example. American Anthropologist 74(3):689–92.

Price, Richard. 1966. Caribbean fishing and fisherman: A historical sketch. American Anthropologist 68(6):1363–83.

Quinlan, Robert. 2005. Kinship, gender and migration from a rural Caribbean community. Migration Letters 2(1):2–12.

———. 2006. Gender and risk in a matrifocal Caribbean community: A view from behavioral ecology. American Anthropologist 108(3):464–79.

Reher, David Sven, and Pedro Luis Iriso-Napal. 1989. Marital fertility and its determinants in rural and urban Spain, 1887–1930. Population Studies 43:405–27.

Richardson, Bonham C. 1975. The overdevelopment of Carriacou. Geographical Review 65(3):390–99.

Richardson, Laura. 1997. Feeding dependency, starving democracy: USAID policies in Haiti. Boston: Grassroots International.

Richman, Karen E. 2003. Miami money and the home gal. Anthropology and Humanism 27(2): 119–32.

Roberts, G. W. 1957. Some aspects of mating and fertility in the West Indies. Population Studies 8:199–227.

Rocheleau, Dianne. 1984. Geographic and socioeconomic aspects of the recent Haitian migration to South Florida. In Caribbean migration program. Gainesville: University of Florida, Center for Latin American Studies.

Rodman, Hyman. 1971. Lower-class families: The culture of poverty in Negro Trinidad. New York: Oxford University Press.

RONCO. 1987. Agriculture sector assessment: Haiti. Marguerite Blemur, ed. Washington: RONCO Consulting Corporation.

Ross R. T., and M. Cheang. 1997. Common infectious diseases in a population with low multiple sclerosis and varicella occurrence. Journal of Epidemiology 50(3):337–39.

Rotberg, Robert I., and Christopher A. Clague. 1971. Haiti, The politics of squalor. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Rouse, Irving. 1992. The Tainos: Rise and decline of the people who greeted Columbus. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rubenstein, Hymie. 1977. Economic history and population movements in an eastern Caribbean Valley. Ethnohistory 24(1):19–45.

———. 1979. The return ideology in West Indian migration. In The anthropology of return migration, ed. Robert Rhoades. Papers in Anthropology 20:330–37.

———. 1983. Remittances and rural development in the English-speaking Caribbean. Human Organization 42(4):295–306.

Safa, Helen I. 1986. Economic autonomy and sexual equality in Caribbean society. Social and Economic Studies 35(3):1–21.

———. 1995. The myth of the male breadwinner: Women and industrialization in the Caribbean. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Sahlins, Marshall. 1972. Stone age economics. Chicago: Aldine.

Saint‑Louis, Loretta‑Jane Prichard. 1988. Migration evolves: The political economy of network process and form in Haiti, the U.S. and Canada. Dissertation, Boston University.

Sargent, Carolyn, and Michael Harris. 1992. Gender ideology, childrearing, and child health in Jamaica. American Ethnologist 19(3):523–37.

Scarano, Francisco A. 1989. Labor and society in the nineteenth century. In The Modern Caribbean, ed. Franklin W. Knight and Colin A. Palmer. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

———. 1984. Sugar and slavery in Puerto Rico: The plantation economy of Ponce, 1800–1850. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Schellekens, J. 1993. Wages, secondary workers, and fertility: A working-class perspective of the fertility transition in England and Wales. Journal of Family History 18: 1–17.

Schwartz, Timothy. 1992. Haitian migration: System labotomization. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville.

———. 1998. NHADS survey: Nutritional, health, agricultural, demographic and socio-economic survey: Jean Rabel, Haiti, June 1, 1997–June 11, 1998. Unpublished report, on behalf of PISANO, Agro Action Allemande and Initiative Developpment. Hamburg, Germany.

———. 2000. “Children are the wealth of the poor:” High fertility and the organization of labor in the rural economy of Jean Rabel, Haiti. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

———. 2004. “Children are the wealth of the poor”: Pronatalism and the economic utility of children in Jean Rabel, Haiti. Research in Anthropology 22:62–105.

SCID (South-East Consortium for International Development) 1993. Report: Farmer needs assessment exploratory surveys: CARE Northwest region 2, 3 & 4 South-East. Richard A. Swanson, William Gustave, Yves Jean, Roosevelt Saint-Dic, eds. Consortium for International Development and Auburn University. Work performed under USAID contract No. 521-0217-C-0004-00.

Scrimshaw, Susan. 1978. Infant mortality and behavior in the regulation of family size. Population and Development Review 4:383–403.

Segal, Aaron. 1975. Population policies in the Caribbean. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

———. 1987. The Caribbean exodus in a global context. In Caribbean exodus, ed. B. Levine. New York: Praeger.

Senior, Olive. 1991. Working miracles: Women’s lives in the English-speaking Caribbean. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sergeant, Carolyn, and Michael Harris. 1992. Gender ideology, child rearing, and child health in Jamaica. American Ethnologist 19(3):523–37.

Sharpe, J. 1997. Mental health issues and family socialization in the Caribbean. In Caribbean families: Diversity among ethnic groups, ed. J. L. Rooparine & J. Brown. Greenwich, CT: Ablex.

Simey, T. S. 1946. Welfare and planning in the West Indies. Oxford: Clarendon.

Simmons, Alan Dwaine Plaza, and Victor Piché. 2005. The remittance sending practices of Haitians and Jamaicans in Canada. At www.un.org/esa/population/publications/

IttMigLAC/P01_ASimmons.pdf.

Simpson, George Eaton. 1942. Sexual and family institutions in Northern, Haiti. American Anthropologist 44:655–74.

Singer, Merrill, Lani Davidson, and Gina Gerdes. 1988. Cultural, critical theory, and reproductive illness behavior in Haiti. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 2(4):379–85.

Skari, Tala. 1987. The dilemma. Refugees March:27–29.

Sloley, M. 1999. Parenting deficiencies outlined. The Jamaica Gleaner Online. At www.jamaicagleaner/1999117/news/n1.html, accessed April 2, 2002.

Smith, Delores E., and Gail Mosby. 2003. Jamaican child-rearing practices: The role of corporal punishment. Adolescence, Summer. At findarticles.com/p/articles

/mi_m2248/is_150_38/ai_109027887/pg_1?tag=artBody;col1.

Smith, Jennie Marcelle. 1998. Family planning initiatives and Kalfouno peasants: What’s going wrong? Occasional paper/University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies, no. 13. Lawrence: Institute of Haitian Studies, University of Kansas.

Smith, M. G. 1957. Introduction. In My mother who fathered me: A study of the family in three selected communities in Jamaica, by Edith Clarke. London: George Allen and Unwin.

———. 1961. Kinship and household in Carriacou. Social and Economic Studies 10(1):455–77.

———. 1962. West Indian family structure. Seattle: University of Washington.

———. 1966. Introduction. In My mother who fathered me: A study of the family in three selected communities in Jamaica, 2nd ed., by Edith Clarke. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Smith, R. T. 1953. Aspects of family organization in a coastal negro community in British Guiana: A preliminary report. Social and Economic Studies 1(1):87–112.

———. 1956. The Negro family in British Guiana. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.