This paper focuses on formal egg production in Haiti. Data is drawn from a review of the literature and contact with farmers, entrepreneurs, merchants, and cooperative leaders. Current value of the Haitian egg market is 36 million USD per annum (MARNDR 2014). That translates to 41.2 million eggs per month; 6.45 million are produced in agro-industrial facilities in Haiti; several hundred thousand are produced on small farms, where reside some 50% of the Haitian population, and in peri-urban environs where ~30% of the population lives; all the remainder are imported from the Dominican Republic (more than 90% in 2012) and, to a far less extent, from the United States (~4% in 2012). Egg production in Haiti fell in the 1980s and 1990s, all but completely disappearing in 1998. During the same time Dominican egg production and imports grew dramatically. Alleging a breakout of bird flu, the Haitian government embargoed Dominican eggs in 2012, something that it had done in 2008 and in fact never formally rescinded. There was, and still is, a massive effort to take advantage of the break in imports to promote national production. Nevertheless, imports have once again informally surged. The prospect of Haiti becoming self-sufficient in egg production is remote. Poor transport, expensive and unreliable electricity, and poor extension services and government support are significant impediments. But the greatest constraint is feed, which is 80% of the cost of egg production. Taking into consideration feed-to-egg conversion ratios, the cost of feed for a single egg produced in Haiti is currently 11 US cents, about the same as the cost of an egg purchased at the border. For those investors interested in poultry, a far more attractive investment is production of broilers (chickens for consumption). However, eggs have an advantage over production of chickens for meat in that they can be stored more easily, at no cost in feed, and they are far more marketable in rural areas.

Formal Sector Egg Value Chain in Haiti

Current Haiti Egg Market

The total value of the Haitian egg market in 2014 was currently estimated at 36 million USD per annum (MARNDR 2014). That translates to 41.2 million eggs per month; 6.45 million are produced in agro-industrial facilities in Haiti; several hundred thousand are produced on small farms, where reside some 50% of the Haitian population, and in peri-urban environs where ~30% of the population lives; all the remainder are imported from the Dominican Republic (more than 90% in 2012) and, to a far lesser extent, from the United States (~4% in 2012).

Declining National Production

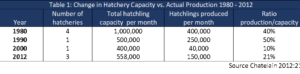

Haiti went from a country that in 1981 produced 80% of what it consumes to a country where more than 50% of the national diet is imported (AFC 2014). Poultry and eggs are an extreme example of the economic decline. In 1980 Haiti had four hatcheries with a total capacity of 1 million chicks per month and producing at 40% capacity. At the end of the 1991 to 1994 international embargo against Haiti the country had a single hatchery capable of producing 500,000 chicks per month but operating at 50% capacity. With the end of the embargo and a new 5% tariff on imported eggs, the sector experienced a slight resurgence, but in 1998 national production all but completely ceased. In year 2000 Haiti’s only hatchery had dropped to a capacity of 400,000 chicks while producing a mere 48,000 hatchlings per month, 10% of capacity and 20% of what was being produced 6 years earlier (see Chatelain 2012). As seen in Table 1 below, the poultry sector has still not recovered.

Urbanization

The decline in agricultural production was not only in the industrial sector. It occurred in the context of a high rate of urbanization. During the same period that production fell, Haiti went from a country where 70% of the population of lived in rural areas or villages and produced food for household or local consumption—such as eggs– to one where 50% of the population is urban and produce little to no food at all. [i]

Dominican Eggs

While Haiti was rapidly urbanizing and the economy was contracting in terms of both agriculture and non-food production, the economy of Haiti’s already heavily urbanized neighbor, the Dominican Republic, was experiencing dramatic growth. Between 1991 and 2013 the Dominican economy grew at an average annual rate of 5.5%, among the fastest in the world. Growth in egg production was among the most vibrant aspects of that growth. Dominican egg production doubled in the years 2004 to 2011. A major outlet for Dominican production was Haiti. In the past 15 years alone the amount of Dominican products entering Haiti have increased 20 fold: official Haiti-Dominican cross border trade went from $71.9 million 2001 to $802 million in 2010. At least 90% of the trade was in favor of the Dominicans. Since the 2010 earthquake trade has doubled again, reaching an estimated USD $1.5 billion. Only $50 million of the current total is in favor of Haiti. Eggs became one symbol of Dominican market success and its domination of Haiti. The significance of access to the Haitian market—illegal since 2008—cannot be gainsaid. Because of the presence of New Castle Disease on the Island, the Dominicans cannot export to any other neighboring islands. Yet, with only Haiti as a trade partner, by 2012 egg exports to Haiti had made the Dominican Republic the third largest exporter of eggs in Latin America and the Caribbean.[ii]

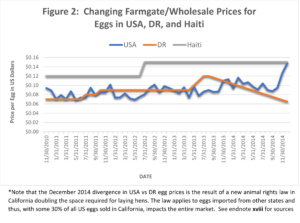

Dominican egg producers have advantages over their Haitian counterparts. They have better roads and transport. But they also suffered the major disadvantage of high feed cost. As will be seen shortly, 80% of egg production costs are from feed and, just as in Haiti, the Dominicans must import feed from the US. But they have reduced cost of feed with government subsidized state of the art processing facilities and they have the strong support directly to the egg producers in the form of technical assistance and government subsidies. Not least of all, the Dominican producers are enjoy a market protected by tariffs that very from 22 to 99 percent. In doing all this the Dominicans are producing eggs on par and sometimes cheaper than US producers (see Figure 2). [iii] [iv] [v] [vi] [vii] [viii]

Renewed Efforts at National Production

In 2007, the Preval administration launched initiatives aimed at encouraging investment in the poultry sector (CNSA 2007). Notwithstanding the Ministry of Agriculture’s “Politique de Développement Agricole 2010-2020” (MARNDR 2009) which included a reduction of the tariff on eggs from 5.0% to 3.5%, the 2010 Plan National d’Investissement Agricole and Plan d’Action pour le Relèvement et le Développement d’Haïti, and its plan for the “Développement de l’Aviculture” was designed to facilitate growth in poulty industry. Chicks were permitted to be imported with only a total of 7% surcharge for taxes, verification and accounting costs. [ix] [x]

The five years since the 2010 earthquake have brought more changes. An avalanche of low interest funding programs and that came about after the earthquake, helped galvanize entrepreneur interest in the sector. Projects launched include,

- USAID/ WINNER dans la région des Gonaïves (50.000 pondeuses)

- PDLH/OXFAM in Paillant (with AFAP)

- USAID/ HI FIVE dans la région des Cayes avec ASSAVIS.

- Pro-Huerta in the North (Argentina)

- Core’s projects at Christian Ville in Gressier

- Christian Aid in the Sudest[xi]

- EcoWorks International (EWI) in Ganthier

Not least of all, in 2011 the Martelly administration renewed the government’s commitment to increased national production on all fronts, especially in the agricultural sector and, more than anything else, in egg production. By 2012 Haiti had 721 facilities producing broilers and 25 producing eggs.

Making the growth possible were three significant hatcheries: Haiti Broilers (capacity = 400,000 chicks per month), JAVEC (100,000 chicks per month) and FACN (50,000 chicks per month). With a total capacity for these three operations of 550,000 chicks per month, if all the chicks were destined to become laying hens, they could, in one year, enable Haiti to produce 6 million eggs per day, significantly more than market demand. It seemed in 2012 that Haiti could become self-sufficient in egg production. It also seems that the Haitian government was keen to take advantage of the opportunity.[xii]

The Egg Embargo

In June 2013, claiming that the Dominican poultry industry was experiencing an outbreak of aviary, flu the Haitian government prohibited the importation of eggs from the other side of the island.[1] It was not the first time. A spate of H5N1 bird flu cases in 2008 resulted in a Haitian embargo against Dominican eggs something that was imposed for the period 2008 – 2013 and never formally lifted. Instead the import deficit was made up for in 2008 and 2009 by importations from the US and thereafter the Dominican imports informally resurged in the wake of the 2010 earthquake. Notwithstanding, within four days of the ban on Dominican eggs the PAHO (Pan American Health Organization) had investigated the 2012 case and rejected the claim.[xiii] [xiv]

The new embargo nevertheless remained in place, helping to promote national production through an increase in prices and giving the Haitian government—which due to its weak economic and trading status has the most liberal import tariffs in the Caribbean–a mechanism to restrict Dominican egg importation at will—i.e. through tightening and loosening control over smuggling. By 2014 heavily capitalized industrial Haitian egg entrepreneurs were producing 6.45 million eggs per month. This was six times the 1 million produced per month in 2006. The most promising encountered during the course of this research is that of Ferme des Antilles, a modern state of the art facility in Cavaillon, Department of the South. According to staff at the facilities, two coups have the capacity to house 20,000 layers and produce 20,000 eggs per day. The corporation has begun to incorporate hatcheries in their operations. According to Kiko Verdier, manager of the Caviallon operation, they have similar facilities built in thre other Departments (North, Plateau Central, and on the border with the Grand Anse) and plan on opening at least on facility 10 of Haiti’s departments. If they succeed, the project will certainly lead to additional investments. However, at the moment the Cavaillon facility operates at less only 25% capacity (5,280 layers), they are able to typically sell eggs at 420 Haitian dollars per case (360 eggs), 13% higher than what eggs can be purchased for wholesale at the border (365 per case). It is also not clear how independent the operation. The owner, Jean Claude Verdier is closely linked to the Martelly administration. Whether Ferme des Antilles will succeed remains to be seen. The analysis below is not encouraging. [xv]

Continuing Under-production

Despite increased production, Haitian national production of 6.45 million eggs per month is still far below the 41.5 million eggs per month that Haitians consume. Moreover, new poultry businesses are producing far below capacity. In mid 2014 Haiti Broilers was producing chicks at less than 50% of its capacity. The other two major hatcheries—JAVEC and FACN–were operating below 25% capacity. Nor should it be overlooked that 70% of Haiti’s hatchery capacity and more than 50% of the feed for chickens comes from a single corporation, Haiti Broilers, without which resurgence in the poultry sector would not have hitherto been possible. Moreover, most of the chicks being produced are destined, not to lay eggs, but rather to get broiled in Haitian cooking pots.

In short, Haiti’s egg production status continues to be discouraging, particularly when juxtaposed with that of the Dominican Republic. Both countries have the same size populations, about 10 million each. But by comparison to Haiti’s 6.45 million eggs produced per month, the Dominican Republic produces 115 to 124 million eggs per month. And whereas Haiti is producing less than 20% of the eggs it consumes and importing the remainder, the Dominican Republic is consuming 80% of the eggs it produces (translating to twice the per capita consumption in Haiti) and exporting the remaining 20%, more than 97% of them to Haiti. The Dominicans are able to wholesale their eggs at 365 Haitian Dollars per case, while the Haitian producers sell 400 to 420 per case, 10% to 13% difference.

Constraints on Intensive Egg Production

The bottom line is that the prospects of egg self-sufficiency through industrial production are still remote. Poor transport and expensive electricity are the first constraints. Any production facility in Haiti must provide all of its own infrastructure. It must import at exorbitant prices all technology, not just that directly necessary for production but everything from tires and motor parts to basic tools. This is to say nothing of the entrepreneurs own needs for maintaining a residence, taking care of a family and meeting the cost of living in a highly underdeveloped economy. All of this makes head to head competition with the Dominicans and even the US difficult if not impossible using the prevailing, state of the art technologies and feed resources.

The greatest constraint of all is feed, which accounts for 80% or more of production costs. Layers must be fed a sophisticated balance of feed enriched with nutrients and vitamins. If the feed is not adequate the hens do not lay. Haiti has three major sources of for balanced chicken feed, all are located in the same 10 square mile area North of Port-au-Prince, distributions networks are weak (see Concluding Complexities, p 20), with Haiti Broilers having the best distribution systems. If an egg producer feeds Haiti Broiler feed then at the current price of USD $16.00 per 55 lb. sack of feed and the optimum conversion ratio of 1 dozen eggs for 4.6 lbs. of feed, the sack of feed will yield 144 eggs; USD $0.11 per egg. Meaning that feed alone makes the Haitian egg more expensive than the Dominican egg.

Making the situation worse, some entrepreneurs interviewed in the course of the field work complained about the Haiti Broiler feed, saying that the hens do not develop well. Others complained about price fluctuations and monopoly control they saw as an impediment to their own success. Mixing feeds on premises is a risky option. It must be done to exact proportions and according to entrepreneurs interviewed during the course of field work it still requires special supplements. As seen, the Dominican Republic has managed the problem with through vertical integration with a high tech agro-industrial feed sector heavily supported by the government. Several Haitian producers reported traveling to the Dominican Republic to purchase the feed supplement. Even staple feed is a major problem. At the best of times, corn costs more in Haiti than the US and the Dominican Republic, which also imports most feed from the US (The Poulrty Site 2008). Rural domestic corn prices fluctuate throughout the year by as much 300%, making investing in corn far more attractive than eggs or even meat production.

Even if the Haitian entrepreneur is able to overcome all the preceding obstacles, to manage a flock he or she must understand and master lighting, molting, special feeds, temperature, humidity, water availability, disease, hygiene and waste disposal, all of which, if not properly managed, will decimate a flock. Salaries for competent management and technology experts are high, something due to massive emigration of college and technical graduates—many of whom head to the Dominican Republic–and grossly inflated wages in Haiti’s robust NGO sector–which pays 2 to 4 times the local wage (see Annex 2). Indeed, pay scales and the cost of living in the Dominican Republic are significantly less than in Haiti for every job from a motorcycle taxi to a policeman to an agronomist. Transport is also cheaper and more efficient; food is cheaper and of a higher quality; and living accommodations are cheaper, more hygienic and more comfortable. What all this means is that by the time the average Haitian agro-industrial egg producer has hired competent management, paid them, figured out how to manage an egg-laying operation and fed the chickens the right food, he or she may have lost her proverbial shirt.

Opportunity Costs

Perhaps most discouraging of all in terms of egg production is that, from the perspective of an investor, it is an unnecessary risk. For those Haitian entrepreneurs interested in poultry, meat production is a far better bet, one with less risk, higher profits, and faster turn-around. A meat producer can purchase a flock of 1 day old chicks from Haiti Broilers at US$0.80 per chick. At the same time they can buy all the feed necessary to nourish the chicks to 45 days of age at which time they can sell the 3.0-3.5 pounds birds for slaughter. In contrast, a layer is not mature until 126 days of age, by which time the meat producer could have cycled through three flocks. The cost of a mature layer is USD $11.00-$12.00. If all goes as planned—there are no epidemics, the feed is balanced, the hens do not get overstressed by heat, and thus the hens lay the anticipated quantity of eggs, and assuming that feed is free– the egg entrepreneur still will not break even until at least 150 days after purchasing the mature layers. Once again, the meat producer would have already completed three investment cycles. And this does not account for investments in infrastructure and labor. The life of the egg investment cycle is about 14 months—the length of time that layers produce the most eggs– which means either purchasing and storing an entire year of feed or running the risk of being bankrupted by fluctuating feed prices.

The overwhelming advantages of investing in poultry for meat versus eggs is manifest in the figures. Of the 746 poultry operations in Haiti in 2012, only 25 produced eggs. In the Department of the South, agronomists working with the major feed and veterinary supply store estimated that less than 10% of all poultry operations produce eggs. But even these figures do not adequately illustrate the risks involved; the same agronomists estimated that more than 75% of the broiler operations South fail.

All that is being described means unnecessarily tying up large amounts of capital for extended periods of time, taking on risk and management of technologically complex operations, doing so in an environment unique in the hemisphere for being radically unsuitable to maintenance of anything high tech, plagued by political and economic instability, all while there are abundant alternatives opportunities to put the capital to work, not least of smuggling eggs from the Dominican Republic.

Continuing Dominican Egg Imports

Although the ban on Dominican eggs was never lifted and the prices remain relatively high, importations through illegal channels have resurged. Eggs are smuggled in disguise, often in Tampico juice boxes, or they are routed through remote border markets such as Pedernales, Ti Roli, and more important than any other for eggs, the border post in the Northern town of Ouanaminthe. Importers as far away from the border as Les Cayes, report making greater profits traveling to Ouanaminthe and returning with eggs than paying local producers. Today, raw eggs sold in the small stores throughout the cities and rural areas of Haiti and boiled eggs sold by street vendors.

Changing Prices

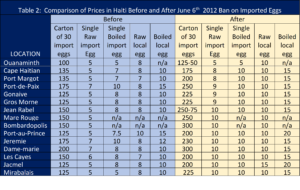

For the 10 years prior to the ban on Dominican Egg imports, prices for eggs remained generally stable, largely due to the stability of prices in the Dominican Republic (see Figure 2 above). Since the ban, wholesale prices at the border have increased from 100 to 150 Haitian Gourdes per carton of 30 eggs (3.3 Htg to 5 Htg per egg). As one moves into the country, for example from the border post of Ouanaminth to Cape Haitian, the price has increase from 125 Htg. Before the ban to a contemporary price of 175 Htg per carton of 30 eggs. As one moves even farther inland and to more remote markets the prices increased from 150 before the ban to the contemporary price of 200 Htg. In even more remote markets the prices have gone from 175 to 225 and 250 Htg. In the most remote market towns, such as Bombardopolis in the North West, the current prices is 300 Htg for 30 eggs.

The impact on retail prices, has meant that whereas before the ban ordinary Haitians could buy eggs at in retail stores throughout the country for ~5 Htg per raw egg and 7 Htg for a boiled egg, the current prices is ~8.3 Htg (3 for 25 Htg) for a raw egg and 10 Htg for a boiled egg.

The price of Haitian eggs, those from small farms and although smaller, widely considered of better quality and better taste, have remained stable in rural areas at 7 to 8 Htg per egg and 15 Htg for a boiled egg. In effect, in rural areas and towns raw local eggs are now the same price as imported or industrial produced eggs and in some cases less expensive. For example in North West market town of Mare Rouge local eggs sell for 7 Htg versus 8.3 Htg for imported eggs. The trouble, for those who want local eggs, is that there are very few available. The scarcity is manifest in Port-au-Prince prices where local eggs sell for 15 Htg per raw egg and 20 to 25 Htg for a boiled egg.[xvi]

As disparaging as the prospects for egg production may be, Dominican imports have their problems too. They must get the eggs to the border. The eggs must cross the border and be transported throughout Haiti, typically in dilapidated vehicles without refrigeration and across rough roads. This means broken eggs, lost time, and spoilage. Having said that, producers in Les Cayes region are getting close to being competitive, sometimes selling eggs for 5.5-6.0 Htg per egg versus the price at the border in Ouanaminthe of 5 Htg. Yet, the 10-13% difference is still enough for major entrepreneurs in the South to travel to the farthest point in Haiti from Les Cayes—Ouanaminth—buy illegal eggs, and then transport them all the back to Les Cayes, risking spoilage, broken eggs, and having to pay bribes at two inspection stations.

The Prospect for Small Scale Egg Production in Haiti

Despite unfavorable tariffs, a lack of government subsidies and technical programs, and a paucity of feed processing facilities there is a very real opportunity for increased egg production in Haiti. There is an enormous demand for eggs throughout Haiti. Even if Dominican imports were to be frozen at the current level, producers can expect market growth. Haitians annually consume only 45 eggs per person—compared to 258 per person in the USA and 200 in the Dominican Republic, the latter figure up from 124 ten years ago. The Haitian government, having restricted Dominican importation, has a mechanism to increase and restrict the importation of eggs at will, artificially raising and lowering prices of imported eggs when needed and giving an advantage to local producers. Eggs produced throughout the country would be closer to markets, meaning less spoilage and fewer broken eggs, another advantage to domestic production. Moreover, eggs have an advantage over production of chickens for meat in that they can be stored more easily, at no cost in feed, and they are far more marketable in rural areas. There may also be alternative means to promote egg production in Haiti, one more in line with the semi-subsistence farming strategies and poor infrastructure that prevails in the country. The major objective of the present research is to figure out how include the poorest and even peri–urban farmers in such an endeavor. We turn now to this topic. The conclusion, as seen below, is that it is difficult to include this segment of the population without introducing new strategies and technologies. In the traditional and prevailing rural households livelihood strategies, rearing chickens has little to with eggs, typically thought of as by product of raising chickens, useful for occasionally consumption, as gifts, and for petty cash.[xvii]

NOTES

[1] It was not the first time that the Haitian Government had embargoed Dominican poultry products. It had done the same thing in December 2008, after 115 cases of the bird flu were reported. Then too smuggling quickly regulated supplies.

[i] According to McKinley and DeWitt, one billion USD World Bank loan to Haiti’s then richest family—the Brandts–would have made Haiti an exporter of eggs. Instead, political instability from 1981 until 2006 was associated with a failure of the Brandt project. In 1998 all closed their doors.

[ii] AlterPresse 2006. Développement durableHaïti- République Dominicaine : Redynamiser la production avicole à l’ouest de l’île http://www.alterpresse.org/article.php3?id_article=5030#.VIuJsjHF9qo

Laboratoire des Relations Haïtiano-Dominicaines (LAREHDO)

[iii] This does not include an additional estimation of $300 million per year in illicit trade, also mostly in favor of the Dominicans.

[iv] For trade see The Business Year, Strength in Solidarity 2013

http://www.thebusinessyear.com/publication/article/14/1632/dominican-republic-2013/strength-in-solidarity

Haiti Grass Roots Watch Haiti-Dominican Republic Trade: Exports or Exploits? Inter Press Service

For growth in Dominican economy see, http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/dominicanrepublic/overview

[v] Fieser, Ezra And Jacqueline Charles 2013 Haiti, Dominican Republic chicken war highlights trade inequitieshttp://www.miamiherald.com/2013/07/07/3489665/haiti-dominican-republic-chicken.html

[vi] For export restrictions because of New Castle disease see The Poultry Site Dominican Republic – Poultry and Poultry Products Report – 2008 Thursday, December 11, 2008

[vii] For taxes see The Poultry Site, http://www.thepoultrysite.com/articles/1261/dominican-republic-poultry-and-poultry-products-report-2008

[viii] For feed costs and importation in the Dominican Republic see The Poultry Site, http://www.thepoultrysite.com/articles/1261/dominican-republic-poultry-and-poultry-products-report-2008

[ix] While the causes of the decline in Haiti’s domestic production, it has been widely argued to have come about as a result of political instability and structural readjustment programs (see Schwartz 2012)

[x] From Chatllain 2012: “Depuis l’an 2008, suite à la découverte du virus H5N1 en République Dominicaine, tous les poussins importés proviennent d’une entreprise basée en Floride dans la région de Miami dénommée MORRIS HATCHERY. Le poussin coute U$ 33 cts /l’unité au USA, le transport aérien U$ 68 cts/livre, représentant à peu près U$ 28 cts /poussin. Comme intrants agricoles, ils sont exonérés de droit de douane et de TCA. Ils ne paient que les frais de vérification 4%, l’acompte 2%, les taxes pour les collectivités territoriales 1%. Les importateurs revendent les poussins à un prix variant entre 30 et 32 gourdes.

Les importateurs de poussins les plus connus sont :

- M&M

- GERMALOT

- VIDRO TRADING

- AHPEL

[xi] http://www.christianaid.org.uk/emergencies/past/haiti-earthquake-appeal/eggs-story.aspx

[xii] On Haiti Broilers, from Chatelain 2012,

“Deux ans après le démarrage de leur opération, 95% des poussins sont produits localement, et tous les importateurs ont été convertis en distributeurs de poussins. Il faudrait que des investissements se réalisent en aval dans les fermes pour justifier le fonctionnement de deux couvoirs et les rendre rentables.

Haïti Broilers dispose d’un réseau commercial de 57 distributeurs répartis sur 8 départements géographiques du pays, dont 47% se trouvent dans le département de l’Ouest avec 27 points de distribution de leur produit dans l’Ouest.

D’une capacité de production de 120 tonnes /jour, l’entreprise développe une stratégie de proximité en allant à la recherche de ses clients. En plus de ses 57 distributeurs, elle déploie sur le terrain 22 médecins vétérinaires pour encadrer les éleveurs. Une particularité de cette entreprise, elle n’offre à ses éleveurs de poulet de chair qu’un seul type d’aliment, une ration unique du premier jour jusqu’à la vente. Bien que ses prix de vente soient plus élevés que ceux de son voisin (IMBA), HAITI BROILERS contrôle environ près de 50 % du marché de l’aliment. Ses matières premières arrivent de Jamaïque et des USA.”

[xiii] Intense negotiations and a backlash from the DR retroactively deprived of citizenship all immigrants from Haiti going back to 1929—an almost comical reaction that would take citizenship away from about half of the greatest Dominican athletes, a sizeable portion of their military, and many notable politicians.

[xiv] Did Haitian Government Lie Over Chicken And Eggs From Dominican Republic?

[xv] La Ferme des Antilles produira par milliers des oeufs et des poulets à Cavaillon Le Nouvelliste | Publié le : 30 juin 2014

[xvi] For USA Egg Prices see, Ycharts which depends on US Department of Agriculture for data, https://ycharts.com/indicators/us_egg_price

For Dominican Egg Prices see,

Diagnóstico situacional sobreEl comercio de pollos y huevos entre república dominicana-haití Acciones en cursoJulio 2, 2013 el Centro de Exportación e Inversión de la República Dominicana (CEIRD) http://www.ceird.gov.do/ceird/pdf/directorio_exportadores/ESTUDIO_SOBRE_EL_MERCADO_DE_POLLOS_Y_HUEVOS.pdf

Hoy Digital Por EVARISTO RUBENS 12 marzo, 2012 12:54 am

http://hoy.com.do/suben-precio-de-huevos-pero-en-granjas-su-costo-es-estable/

Hoy Digital Precio de huevos alto a pesar de exceso de producción 10 julio 2013

http://www.elsitioavicola.com/poultrynews/26677/precio-de-huevos-alto-a-pesar-de-exceso-de-produccian#sthash.EbnPaKX7.dpuf

Asohuevos

[xvii] For US egg consumption see, US egg consumption highest it’s been in 7 years: ‘Protein is where there is a big opportunity right now.’ By Elaine Watson+, 24-Oct-2014. http://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Markets/US-egg-consumption-highest-it-s-been-in-7-years

For Dominican consumption statistics see Estudio Sobre El Mercado de Pollos y Haiti, (http://www.cei-rd.gov.do/ceird/pdf/directorio_exportadores/ESTUDIO_SOBRE_EL_MERCADO_DE_POLLOS_Y_HUEVOS.pdf), and then do the math, 2 billion eggs divided by 10 million people

Also see The Poultry Site for past statistics Dominican Republic – Poultry and Poultry Products Report – 2008 Thursday, December 11, 2008

For Haiti, the math is 42 million eggs divided by a population of 10 million