Infants in Haiti face an especially daunting set of nutritional challenges. The 1,000 days from conception to a child’s second birthday are the most critical period of a child’s physio-intellectual development. Children who are well nourished during this period become healthier and more intelligent adults who in turn are better able to feed and care for their own children. Those who are poorly nourished during this period are more likely to develop low intellectual capacity, physically stunted bodies and weak immune systems, all factors that contribute to the cycle of societal underdevelopment and continuing poverty. [i]

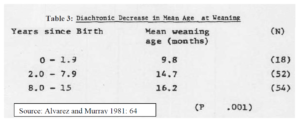

Breastfeeding can help mothers provide babies with nutrients that foster growth, and antibodies that dramatically lower risk of illness. Cognizant of this, international health organizations have for a half of century invested heavily in mother/child nutritional health information campaigns designed to instill in Haitian mothers the benefits of breastfeeding. These educational efforts may have backfired. Evidence from the field suggests that before these campaigns, Haitian women typically breastfed for 18 months or more. Development practitioners first began pushing six-months of exclusive breastfeeding under the assumption that poor, breastfeeding mothers were also feeding infants powdered milk, when in fact most were not as they could not afford to do so. Over time, Haitian women reduced their time of breastfeeding from 18 months to the “recommended” six months (Table 1). Alvarez and Murray attribute the reduction to economic stress associated with rising food prices that meant women had to work more, and sell more in the market, reducing the time they were able to breastfeed. But the extent and intensity of the mother-child nutrition campaigns—including 50 years of radio announcements, seminars, and training of nurses and auxiliaries who carried the message, over and over, to every one of the hundreds of clinics, hospitals, midwifes, and auxiliary health programs in the country –may have inadvertently contributed to the decline in the duration of breastfeeding.

The call for six months of breastfeeding may have gotten through, but the appeal for “exclusive” breastfeeding appears to have been less effective. Researchers estimate that as few as 20% of Haitian women breastfeed exclusively for the first six months of an infant’s life; purgatives are common; many Haitian women resolutely refrain from breastfeeding neonates, interpreting anti-biotic rich meconium as something dangerous; and women begin introducing teas and even solid foods into a baby’s diet often within days of birth. In one focus group we conducted in 2014, a woman underscored the determination with which many mothers cling to traditional feeding strategies despite the entreaties of healthcare workers, saying, “Everyone here in this group is Haitian, and [let’s just admit] we all give tea at 8 days of the child’s life.”[ii]

One explanation for the introduction of teas and porridges within days of birth is similar to the one Alvarez and Murray offered for the decline in breastfeeding: it might simply be a strategy to help mothers resume revenue-producing work as quickly as possible. In understanding this, Haitian women are among the most economically active female populations in the world (IDB 1999; CARE 2012). The most common female career is itinerant trade involving extensive travel on foot, pack animal or in cramped buses. Selling often occurs in qualitatively filthy market spaces. These factors make it difficult, imprudent, or simply impossible for mothers to bring babies along. Thus, as postpartum women face pressure to resume their trade activities and produce income, they must ensure that their infants are accustomed to a variety of nutritional sources so the babies can be left in the care of relatives or teenage nannies. (Alvarez and Murray 1981; Schwartz 2009; CARE 2012).

Moreover, the importance of female trade to household sustenance means that it is often in the economic interest of the entire family to wean the child earlier than desired or than healthcare workers recommend. Reinforcing this drive are folk rationales for depriving children of milk and putting the blame for consequences of infrequent or brief breastfeeding, not on deprivation of milk, but on the milk itself. For example, the widespread popular class concept of let gate (sour milk) holds that a mother’s milk can spoil if she is angered or startled. The situation is thought of as dangerous to the mother, even life threatening, and the milk is considered harmful and even deadly if fed to the infant. International health workers might find it ironic that, after all the breastfeeding campaigns, even middle class Haitian mothers believe that the milk of a woman who has been startled or angry will give a child severe diarrhea (see Alvarez and Murray 1981; Farmer 1988; Roman 2007).

WORKS CITED

Alvarez and Murray, 1981Alvarez, M.D.Murray, G.F. Socialization for scarcity: Child feeding beliefs and practices in a Haitian village. United States Agency for International Development

CARE 2012 Gender Survey CARE HAITI HEALTH SECTOR Life Saving Interventions for Women and Girl in Haiti Conducted in Communes of Leogane and Carrefour, Haiti Farmer 1988

Farmer, Paul, 1988Bad Blood,Spoiled Milk: Bodily Fluids as Moral Barometers in Rural Haiti (1988)

IDB Inter-American Development Bank (1999). Facing up to Inequality. Washington D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank.Schwartz 2009

Roman S.B. (2007). Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices in Rural Haitian Women. UCHC Graduate School Masters Theses 2003–2010. Paper 141.

USAID 2019 https://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do/global-health/nutrition/1000-day-window-opportunity

NOTES

[i] see Nestle site for summary of impact of first 1,000 days, http://www.nestlenutrition-institute.org/Resources/Library/Free/theNest/nest31/Pages/Nest31.aspx

[ii] Resistance to exclusive breastfeeding and inadequate knowledge regarding treating child malnutrition are areas where intervention programs are many, where they have long had a significant impact, and where it is believed there is ample room for continued investment. (USAID 2019).