This is a historical summary of CARE International’s activities in the region sometimes called “Far West” Haiti, specifically the Department of the North West communes of Jean Rabel, Mole St. Nicolas, Bombardopolis and the neighboring Department of the Artibonite commune, Anse Rouge. The reason the region is of interest to me is that between the years 1991 and 2000 I conducted my doctoral Dissertation research there and I have done at least five different studies in the region, including a major survey funded by the German government. I have also maintained contact with many people in the region. At least half of the surveyors working with me on any given project come from the region, many of them having known me since they were children.

History of CARE International and USAID Development Efforts in Far West Haiti

CARE goes to Haiti

CARE first came to Haiti in 1954 after Hurricane Hazel but significant involvement in the North West began in 1965 when US Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s personal physician happened to visit the region. As the story goes, when the doctor returned to Washington, he briefed Humphrey on the poverty in the region and the near total absence of any significant services or development. The Vice President sent the word down that far NW Haiti was to be developed. USAID soon sent out a call for proposals. CARE, CRS and World Church Service bid on the contract. CARE won.

HACHO

HACHO (initially called the Haitian-American Community Health Organization the name was later changed.) was the organization subsequently formed to develop North West, Haiti. HACHO was a largely USAID funded alliance of GOH and NGO partners. CARE became the principal US party. Not unlike its more recent relationship with PRODEP, CARE staff worked with, trained and advised government counterparts who shared the same office space with them. Government partners included ONAAC (Office National d’Alphabetisation et d’Action Communautaire, focused on literacy); PIRNO (Programme Integree de Rehabilitation du Nord-Ouest – was infrasructure program), and PDAI (Projet de developpement agricole integree – was agriculture). CARE also partnered with organizations such as German Fonds Agricol (the precursors to later PISANO and AgroActionAlemande). Infrastructural Projects were conceptualized as “self-help” and carried out by organizing and partnering with “community councils.” The HACHO development program was comprehensive. It included work in health, education, governance training, small enterprise, agriculture extension services, micro-credit, reforestation, water and sanitation projects, rehabilitation of roads and irrigation works and emergency food relief. HACHO helped feed people and save lives during droughts in 1965-68, 1974-77, 1978-79, and after Hurricane David in 1979. The scale of work was such that CARE director Tim Lavelle (1977 to 1979), likened HACHO to a “quasi-government” (Lavelle notes that the State was essentially absent in any other ‘developmental’ form in the North West). In its 15 years of existence (1966-1979) HACHO gave the North West,

-280 miles of rural roads improved and maintained

-107 miles of major road reconstructed

-60 rural potable water systems built and maintained

-24 irrigation systems

-2 million plus tree seedlings planted

-540 miles of soil conservation-related rock walls

-8 supervisory credit schemes launched with community councils

-129 community councils supported and nurtured

-15 handicrafts production centers

-one beekeeping center (established in Jean Rabel)

-9 hospitals and dispensaries improved and maintained (including the 38-bed Jean Rabel Hospital)

-6 nutrition centers

In 1979 USAID cut funding to HACHO. The reasons are not entirely clear. Officially, USAID had been trying vainly for several years to get the GOH to assume full responsibility for the organization. However, in a 1983 post-project evaluation of HACHO, USAID evaluators criticized its centralized decision making, the remoteness of the central office from targeted beneficiaries, and not least of all, the “tension between HACHO’s relief programs and its development objectives that skewed its development efforts toward non-sustainable programs requiring outside subsidies to keep them operating.” Perhaps more important than anything, they cited lack of accountability, lack of Monitoring & Evaluation, and absence of institutional memory, concluding that, “HACHO had little capacity to identify in any systematic way where it had been, what it had done, and where it should go.” (p 8). Ten years later, CARE would embark on a successor program far larger than HACHO. But what occurred in the meantime brought important lessons.

The Interim Years and Revolutionary Development

The years following the closing of HACHO were tumultuous throughout Haiti. In Port-au-Prince and other cities–notably Gonaives–they were years of increasing popular uprisings and in 1986 the Duvalier (son) regime was overthrow. In the North West there was a parallel but distinct movement. It was agrarian, it was closely linked to development, and it is critically important in understanding the feverish hope that development and reform ignited among impoverished cultivators in the North West. And it failed miserably. Indeed, it ended in tragedy.

For purposes of this review, here are the most salient points: Just as HACHO was being shut down in 1979, a swine flu epidemic swept through Haiti. To combat it, the OAS sponsored a 1983 eradication of all Creole pigs in the country. US veterinarians accompanied by military attaches swept through the region and slaughtered the farmers pigs. Farmers were scheduled to be compensated but corruption meant that most were not. Many of them saw this as a type of attack on their livelihoods.

At the same time that USAID was sponsoring the slaughter of Haitian pigs in the region, Haitian Catholic priests working with the Catholic relief organizations Caritas had begun work in the area. Supported with 20 tons of flour, 30 tons of powdered milk and 4,800 pounds of butter per week from the European Community (according to then Caritas administrator), they organized farming cooperatives, built irrigation works, and led a development and agrarian reform initiative that sought to empower peasant farmers. With the backdrop of events on the national level–the fall of the government and promise of widespread social change–a wave of revolutionary fervor swept through the Far West (as the extreme three communes of NW Haiti plus the Artibonite commune of Anse Rouge are called). It was focused in Jean Rabel but it was a movement that engulfed the entire region. From Port-de-Paix to Mole St Nicolas and Anse Rouge, there was an electric sense of unity in the belief that change could and would come from development linked to community action campaigns.

The movement took on a tone of increasing hostility. To many peasants the recent pig eradications were symbolic of economic aggression and trickery veiled in the guise of foreign-led “development”. In one case, a group of peasants cut the throats of all the pigs at an OAS sponsored IICA porcine re-population center (following the US sponsored 193 eradication of the local Pigs, the US government with OAS had tried to introduce a large White Iowa pig; see ##). The movement began to take on the dimensions of a revolution. As a priest present at the time explained to me when I first visited Jean Rabel in 1990, “to progress it is sometimes necessary that the people break the hand that holds them down.” According to many people living in the area aggression came principally from rural farmers and their animosity and demand for change was widely interpreted among villagers, protestant missionaries, non-Catholic NGOs, and large land owners as a very real threat to the latter’s safety and living standards.

In 1987, with the complicity of the military, counter-reform minded farmer cooperatives allied with villagers and the few large landowners in the area and attacked and massacred 139 of those associated with Caritas peasant development groups. The movement was quelled. Caritas withdrew from the region. Frightened and disappointed reform-minded peasants went back to their little agricultural plots.[i]

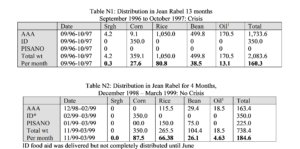

CARE: NW Quasi-Government Era

In the early 1990s CARE became the primary vector of post-Duvalier USAID funded development for the region. Just as HACHO before them, they worked at a comprehensive array of development activities becoming a type of quasi government. CARE activities included everything from agricultural extension services to rehabilitation of road, and irrigation works. CARE touched almost every aspect of people’s lives. Latrine building, contraception, water, nutritional aid to children and lactating mothers, and conducting long term educational development planning and school assistance (DAP I and DAP II). CARE was also the single greatest source of emergency food relief. During and after the 1992 drought, CARE spent 18 months providing daily rations of USAID food aid to 708,200 of the North West and Upper Artibonite’s 860,972 people. Between 1995 and the early 2000s its school feeding program provided daily meals to children in 2000 of the region’s primary schools. [Although outside the Far West region, it is notable that in the 7 weeks following the 2004 Gonaives flood, CARE distributed 2,249 MT of food to 160,000 people].

By the time of the Gonaives flood in 2004, CARE had carried out more regional relief and development projects than any other organization before or since and was far and away the most influential foreign organization working in the region. Where in 1979 HACHO had employed 200 Haitian national staff, maintained 15 vehicles including trucks and 2 Caterpillar bulldozers, in 1999 CARE employed 700 nationals, had 158 motorcycles, 60 SUVs, 25 freight trucks, 2 dump trucks, 1 back hoe, and 12 generators ranging from a 6.5 kW that could run a U.S. household to a 150 kW that could run an entire Haitian village. Where in 1999 HACHO had a main office in Gonaives and field offices in Jean Rabel, Bombardopolis, Anse Rouge and Terre Neuve; by 2004 CARE had expanded to Pas Catabois, Port-de-Paix and Gros Morne and delivered food as far away as St Louis du Nord, essentially covering the entire Department of the North West. At that time CARE was bigger and had more resources at its disposal than the corresponding Haitian government institutions or all the other NGOs in the region combined.

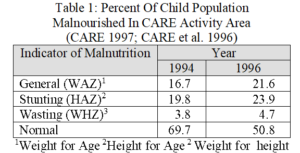

But results were mixed. For example, CARE’s 1994 to 1996 feeding program was the most massive and concentrated feeding program in Haitian history. But CARE researchers found that child nutritional status worsened. Both chronically and acutely malnourished children increased more than 20 percent. And it was not because of the drought–it had ended in 1994. Overall, studies indicated that real per capita income for local farmers had fallen from a per capita 1977 index of US$54 to a mid-1990s level of US$22.[ii]

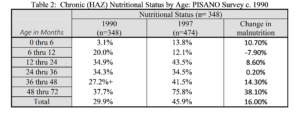

CARE was not alone in noting that development did not seem to be working. The German government had a similar widespread quasi-government operation in the region. Managed by organizations PISANO and AgroActionAllemande (reincarnations of Fonds Agricole that was present during the Hacho era), they too were rehabilitating roads and irrigations works, providing health and agricultural extension service, and distributing massive quantities of food aid. Together, the two German organizations were distributing 10% of all German overseas food aid in the North West. But they noted the same trends that CARE found: dramatic increase in malnutrition occurring over the same period they were providing relief and carrying out widespread development and health programs. [iii]

The same was true for the French. The French Government also had quasi-government programs run through Initiative Developpment (ID). Between 1993 and 1998, ID capped 67 water sources and took over financial and administrative responsibility for the Jean Rabel hospital paying the salaries of 25 of the 54 State employees employed there. ID also created a support network of over 115 regional health auxiliaries, another network of barefoot veterinarians, and engaged in agriculture and livestock support programs throughout the Far-West. But ID staff also noticed that development wasn’t having the intended impacts. Peasants showed little interest in ID’s project to reintroduce the creole pig; and the ID farmer supply store went into the red. In 1993 the ID country director documented the plummeting local price of corn with every new shipment of French corn that his organization monetized on the local market (the French were bringing food too). Adding the all too familiar insult, in 1999 a chanting hospital staff closed a meeting between ID and CARE with chants of “CARE, CARE, CARE,” which paid higher salaries and which they earnestly hoped would take over administrative and financial responsibility from the effective but frugal French. In year 2000 ID pulled out of all its agricultural and health programs, including support to the hospital, and re-focused on education. [iv]

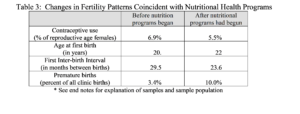

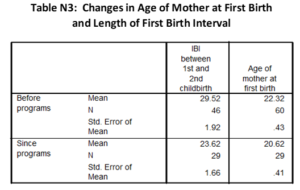

Looking back on the 1990s, what had become a painfully obvious failure in long term development strategies was also evident in health and reproductive statistics. Data from Faith Medical Clinic, located in Mare Rouge and one of CAREs partners in the 1990s, illustrates the point. A comparison of 1980s data with health data collected in the mid to late 1990s showed a 20% decrease in contraceptive use (from 6.9% to 5.5% of reproductive aged women); a 2-year decline in the average of the mother’s age at first birth (from 22 to 20 years of age); and a 5.9 month decline in the average length of a woman’s first inter-birth interval (from 29.5 to 23.6 months). In effect, while three of the world’s most powerful governments–the US (CARE), the Germans (PISANO and AAA), and the French (ID)–where conducting what amounted to a massive contraception and maternal health campaign, women were using fewer contraceptives, have children younger, and getting pregnant more often. As if that was not gloomy enough, premature births over the same period went from 3.4% to 10.0% of all births.[v] [vi] [vii]

Not only was aid during those years not being effective in the long run, it was engulfed in conflict, particularly regarding food distribution. Sacking of CARE trucks and warehouses were common occurrences. Estimates of embezzlement in school feeding programs ran as high as 90%. On at least two occasions’ during the 1990s revelations of corruption prompted CARE to dismiss its entire staff working in food distribution. And once again, CARE was not alone in its frustrations. PISANO had similar problems with embezzlement, theft and seemingly ungrateful beneficiaries. On at least two occasions AAA staff tried to cut food for work projects and found themselves quite literally under attack. In 1997 local peasant leaders took to the airwaves and threatened the life of the field director. In year 2000 a peasant group marched on AAA headquartered in Boucan Patriot and Haitian National Police had to be called in to rescue the staff. With 1987 in the background, such incidences were taken very seriously.

Indeed, no one working in the area can be left out of the equation. The World Food Program came to the area three times during the 1990s. In every instance corruption, logistic complications and poor administration meant that aid missed it mark. Twice the aid, sent for emergencies, was delivered a full year after the crisis and in the midst of bumper harvests. In 1998 a WFP rented warehouse was sacked in Jean Rabel (disappointed pillagers found the food was spoiled).

Nevertheless, whether other international organizations were present or not, CARE was the biggest of all the organizations and it was seen and is still remembered by most people in the area– including its own staff–as a wasteful and inefficient giant that was encouraging corruption and enriching the greedy and immoral. These factors, together with the influence over daily operations of its massive US sponsored food distribution, caused CARE to question the long-term impact of its most significant programs. In 2007 CARE closed most its programs in the region. Citing entrenched politics, widespread corruption, and frustrated with continually declining regional living standards and their own institutional dependency for funding on monetization of US surplus food aid as well as the apparent ineffectiveness of the food, CARE decided to reduce its North West activities. [viii]

Conditions Since CARE Left

In the decade following CARE’s 2007 withdrawal from the region. Missionaries in the Far West report a 2008 spike in cases of malnutrition, but rates subsequently continued to fluctuate within normal bounds.

At least part of the reason that nutritional status in the region did not change for the worse is that the World Food Program (WFP) stepped in and took over the distribution of food aid to the region. The delivery of food under WFP was reportedly similar in both inefficiency and impact to when CARE managed the programs. In a survey of eight community leaders throughout the region, most saw little difference between CARE distribution in the 1990s and early 2000s and more recent WFP food distribution. In a November 2011 interview the country Director of AAA– who with 10 years working in the Far-West is the longest standing country director in the region and perhaps all of Haiti– complained that poor coordination between WFP and his organization, a lack of sensitivity on the part of WFP for how long a crisis endured, use of multiple partners that also do not coordinate, and excessive food relief efforts with respect to the local market undermined his organizations programs and undermined market prices for the farmers. On an equally discouraging note, nutritional clinics also reported problems with the quality of the WFP food. The food is often infested with bugs, something that two clinic directors spontaneously elaborated on in a 2011 interview with me as discouraging recipients from coming to the nutritional clinics. None of this is to say that needs in the region had diminished. On the contrary: The conclusion that warrants emphasis is that there continued to be chronic unmet needs. [ix]

Long Term Development

After CARE reduced its presence in 2007, German AAA continued to be a major organizer of road and infrastructural works in the Far West, much of it funded with WFP food and cash for work. ID continued to work in Education as a partner with Ministry of Education and spawned a sister organization ADEMA, that still works in infrastructure and agriculture. ACF moved in the region with plans to become a major presence on par with CARE of the 1990s. Government organizations FAES and PRODEP gave the GOH a respectable presence that did not exist before CARE left. Some one dozen missionary organizations, most of them with decades working in the region, continued to do infrastructural work; CAM, UEBH, and NWHBM exponentially increased their work efforts becoming as or more significant in terms of effective aid than corresponding government institutions and far more effective in the field of health than any other secular organization (indeed there were no secular organizations in the region working in health care.).

Regionally, the UN had accomplished a series of major undertakings. Where in year 2000 not a single bridge existed in the entire North West, by 2011 the UN had built a dozen modern bridges, Only two of the major river crossings along the entire route from Gonaives to Port-de-Paix and to Jean Rabel no longer had a bridge. Gonaives, destroyed in the 2004 flood and then again in the 2008 floods, was once again a city with at least one consistently paved road bisecting it.

NOTES

[i] Jean Marie Vincent–priest, Liberation Theologist and close colleague of later president Jean Bertrand Aristide–came to live in the village of Jean Rabel. Father Vincent worked with Catholic development organization Caritas.

[ii] This is calculation is based on the US consumer price index, which went from 62.1 in 1977 to 168.3 in 1999 (Global Financial Data 2000). The data for 1977 comes from USAID (1977) . They measure something but I do not believe that either of these estimates can be considered as accurate.

[iv] In the summer of 1997, a United Nations construction team came to the village with a dazzling array of heavy equipment, including air support from helicopters, to renovate the local high school. In 1997, the Voice of America donated equipment that made the founding of a village radio station possible.

[v] In 1989 FMC was the only clinic providing contraceptive services in the immediate region and had 581 women using contraceptive pills and Depropravera. The population rose from 45,000 to a 2000 level of about 60,000 with three clinics providing chemical contraceptives. The total number of users for all three clinics in year 2000 was 660 women. Thus while the overall population had increased by almost 50% the number of contraceptive users has increased by only 20%, a net decline in users from 6.5% to 5.5% overall.

[vi] The difference in mean age at first birth is statistically significant (c.i. = .95). The difference in birthintervals is not significant and a larger sample size is necessary to clarify the importance of these changes. However, this should not distract the reviewer from the fact that if these changes are approximately correct–and the overwhelming statistic probability is that they are— they indicate an alarming increase in fertility among a group of young women who already had alarmingly high fertility levels. And at the very least, the data indicates no decrease in the length of birth intervals and no increase in the age at first birth, observations that suggest minimal receptivity to reproductive health educational efforts sponsored over the past decade by international intervention agencies.

[vii] The data is 20 out of 581 women to 21 out of 210 (sample is from parity of women on family planning lists).

[viii] CARE was not alone in its frustrations. Similar problems in 1998 led ADRA to freeze and then abandon involvement in food aid. Up until 1999, German organizations AAA and PISANO–which had been working in the North West since the 1970s in the form of Fonds Agricole– distributed food and cash to farmers as payment for work done around their own homes (retention ponds), and in their own fields (erosion-control walls and ditches). On at least two occasions in 1997, politicized farmer groups benefiting from AAA food-for-work projects threatened to run AAA out of the area for trying to disassociate project interventions from food payments. In the most dramatic of these incidents, AAA reduced its emergency food relief after the 1997 drought and a group of farmers went on public radio and broadcasted a death threat aimed at the AAA director. AAA initially opted for a short-term solution by leaving the food-for-work program in place. But in 1999 the director again announced that the practice of paying farmers to work on their own fields was being stopped. On a Sunday in January 2000 a group of farmers once again marched on AAA’s rural Jean Rabel headquarters. This time it looked as if the farmers would become violent. AAA staff barricaded themselves inside the building and radioed for the police (who arrived in PISANO vehicles and quelled the uprising).

[ix] Some respondents remarked that CARE was more effective in reaching intended beneficiaries. One noted reason respondents gave was that CARE involved people in the localities as participants: as one respondent said, “yes there was waste, but at least the most vulnerable people got some food.”