This paper summarizes the history of cacao globally and in Haiti, and then explores the cacao value chain in Haiti’s two cacao growing region, the Department of the Grand Anse communes of Chambellan, Dame-Marie, Anse d’Hainault and Irois, and Department of the North communes of Borgne, Port-Margot, Grande Rivière du Nord, Acul du Nord and Milot.. The research is from a review of the literature, dozens of key informant interviews and twelve focus groups that included each of Haiti’s 12 cacao cooperatives–seven in the Department of the North and five in the Grand Anse–a cacao producer survey of 201 randomly selected household in the Grand Anse fund by Root Capital and a 1,147 respondent survey funded by IDB and CRS in both the Grand Anse (589 respondents) and the North (567 respondents). Readers interested in more details about the methodology as well as findings can go here.

Cacao Value Chain in Haiti

Review of the Literature

History of Cacao

Cacao originated in the Amazon and Orinoco river valleys in South America and has been an important crop in the region since pre-Columbian days. The Olmecs of Meso America and then the Mayans and Aztecs who came after them brewed cacao into a drink or gruel (Coe and Coe 2013). Both latter societies considered cacao a gift from the gods. Cacao pods were Mayan symbols for life and fertility and the seeds were used as currency (NIIR 2012). Western scholars echoed these beliefs when they gave cacao the Latin name Theobroma cacao of the genus Theobroma, a Greek term for “food of the gods.” Several cacao producers who participated in focus groups conducted during the course of the present research referred to cacao as their “source of life” – just as the Mayans did.

Prior to the 19th century production and export to more developed countries were limited by heavy taxation in Europe (Capelle 2008). Taxes on cacao in Europe were eventually lowered, and in the 19th century the spread of the steam engine facilitated mass production of chocolate products, making them more affordable. In the same era, producers – including Cadbury, maker of the first popular chocolate bar – began making chocolate more palatable by adding milk and sugar, further increasing demand and encouraging production. (Bensen 2008).

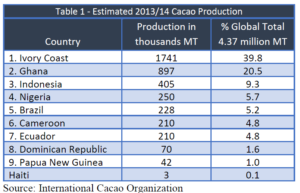

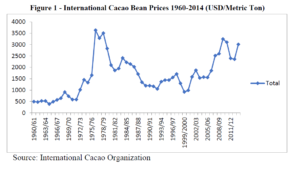

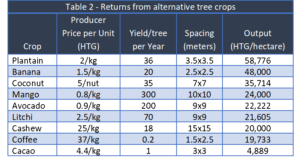

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries cacao, which grows in a belt between 10ºN and 10ºS of the Equator, had become a major export from equatorial regions of the developing world. Today, the world’s main producers are in West Africa, which is forecast to produce nearly three quarters of the world’s supply this year (See Table 2). The other cacao-producing regions, the Americas and Asia/Oceania, are expected to produce 15.3% and 11.6% of global output, respectively. Most of Africa’s cacao is exported from Ivory Coast, the leader with 39.8% of projected 2013/2014 global production, and Ghana, with 21.2% (ICCO Quarterly Bulletin of Cacao Statistics). The two leading countries produced 58% of global output in 2012/2013 despite a decrease of 85,000 tons in their production levels, to 2.28 million tons (ICCO Annual Report 2012/2013). Ninety-five percent of the global cacao supply is produced by smallholder farmers on groves of four hectares or smaller, nearly all of them in developing countries (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Growth in the international market and prices tend to rise and fall in 15-year cycles, creating at type of boom and bust cycle for farmers.[i]

Cacao Production in Haiti

Haiti has two principal cacao growing regions, an estimated 4,000 small farmer households who produce cacao in the Department of the Grand Anse communes of Chambellan, Dame-Marie, Anse d’Hainault and Irois, and some 3,000 in the Department of the North communes of Borgne, Port-Margot, Grande Rivière du Nord, Acul du Nord and Milot. Their contribution to the world supply of chocolate is minor (see Table X), but for Haiti itself cacao beans have been an important crop. Although produced during the colonial area, cacao became a more important source of foreign exchange after independence. In the late 19th and early 20th century, cacao, along with coffee, accounted for the biggest share of Haiti’s exports (IDB 2005). The country’s cacao bean production declined through much of the 20th century, in part due to a mid-century period of low international cacao prices relative to prices of subsistence crops (Bourdet and Lundahl 1989; See Table 2).

Another drag on Haitian cacao prices, and, consequently, production in the 20th century was a lack of competition among buyers. The history of cacao in Haiti is one of monopoly and over-taxation that parallels that of the 19th and 20th century decline in coffee production (Trouillot 1990). In 1960, the Haitian government created the Haitian Manufacturing and Specialty Company, a cacao monopoly, which paid low prices to producers, further discouraging production Bourdet and Lundahl). HAMASCO was abolished in 1978, but today quasi monopolies continue to characterize the cacao market chain in Haiti, with Maison Geo Weiner SA (Café Selecto) dominating the cacao trade in the Grand’ Anse and Maison Novella in the Department of the North (IDB 2005) [ii] Geo Wiener S.A. is a 1996 reinvention of Geo Wiener et Co, a coffee and cacao purchasing company that has dominated cacao purchases in the area for at least 100 years. The company has a facility near Jeremie and a nursery producing 100,000 plants a year, part of an effort to expand Wiener cacao operations. The company, which employs 20 full time staff and 150 seasonal workers, buys from 5,000 farmers. It was responsible for 1,080 MT of Haiti’s 3,800 metric tons of cacao exported in 2008 (IFC 2011).

The suppression of prices has discouraged investment by Haiti’s cacao farmers. Smallholder farmers who participated in focus groups for the present research blamed the decline on low prices that resulted from a marketing chain in which exporters of Haitian cacao exercised monopoly power, setting prices low and discouraging production. Prices have fallen so low at times that some smallholders cut down cacao trees and replaced them with yams or other crops (Root 2014). These discouraging factors are related to four principal constraints on cacao bean production in Haiti: Lack of access to international markets; Age of plants (far beyond peak production years); Poor grove maintenance; Absence of fermentation facilities necessary for the production of the highest quality cacao (IDB 2005, AVSF 2013). Each of these obstacles has concrete effects on cacao harvests:

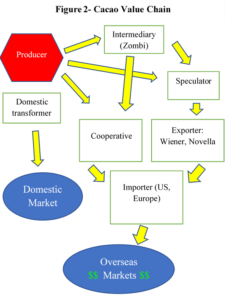

- Lack of market access: Participants in focus groups interviewed for the present research complained that the only significant outlet for their production is a network of middlemen selling to a single exporter dominating the trade in their region – Maison Geo. Wiener S.A. in the Grand’ Anse, and Maison Novella in the North Department. As a result, farmers say they have no choice but to accept whatever they are offered from a network in which two exporters set the prices, and 1,250 intermediaries and 250 licensed speculators take a share of the revenue from the cacao produced by approximately 20,000 smallholder producers (IDB 2005). In some circumstances (when selling crops early in the harvesting cycle to secure short-term financing), Haitian growers receive less than 30 percent of the FOB price. Their counterparts in Ghana, by comparison, receive as much as 80 percent of the FOB price (IFC 2011).

- Age of plants: Cacao trees typically become productive three to five years after planting, and should remain productive for 25 years . Most of Haiti’s cacao trees are more than 50 years old, and 80% of the country’s 16,000 hectares planted in cacao are in need of replanting (AVSF 2014). At a cost of US $3,000 per hectare, the required investment would reach $38.5 million (The Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Rural Development; MARNDR 2012).

- Poor grove maintenance: Informants in the present research said that even at relatively high local 2014 prices of roughly 25 HTG (approximately .46 USD) per pound, many farmers cannot afford to hire day laborers needed to properly clean their groves and trim cacao and shade trees after the two principal harvests (in spring and fall). As a result, most cacao plantations in Haiti have more than the recommended 50% shade, and trees taller than the recommended maximum height of five meters. Too much shade reduces yield; excessively tall trees leave pods at the tops of trees, where, when attacked by Black Rot, they can drip Phytophthora spores on healthy pods below. These and other impacts of inadequate maintenance contribute to low productivity – 226 kg/hectare in Haiti, compared to 800 kg/hectare in the neighboring Dominican Republic. Simple pruning and stand maintenance can increase yield on shaded farms by 30-50% in the first year, and eliminating pests can boost yields further, as rats alone can destroy as much as 25% of the crop (SECID 1999).

- Absence of fermentation facilities: Fermentation is a required step in the preparation of the highest quality cacao beans. In Haiti, only 5% of production is fermented (AVSF 2014), so the vast majority of cacao produced in Haiti is not fit to be sold in the upper echelons of overseas markets. This prevents significant sales of Haitian cacao to importers, primarily in Europe, that pay a premium for cacao deemed “fine or flavor.” As a result, 75% of Haitian cacao is purchased by U.S. bulk importers of “ordinary” cacao beans. This partly explains why the average price for Haitian cacao is lower than that of other producers. For example, Haitian cacao beans sold for US $1,661 per ton in 2003, compared to $1,904 for Dominican cacao, $2,086 for Ivoirian cacao, and $3,197 for Jamaican cacao (IDB 2005).

Interventions in Haiti’s cacao industry

Despite myriad production constraints, cacao is considered to be one of the primary potential sources for development in rural Haiti. The country’s cacao bean exports – 28% of the country’s agricultural exports — have been growing at a rate of 9% per year, and are expected to continue rise at that pace, mirroring increases in U.S. demand (IFC 2011). Although Haiti is not currently classified as a producer of “fine and flavor” cacao beans, it has the potential to become one. Only about 5% of the world’s cacao trees are of the Criollo and Trinitario varieties that produce the beans used in the finest chocolates. In Haiti, however, these varieties represent the majority of trees, so Haitian cacao could be sold at higher prices if properly processed.

The cacao value chain in Haiti involves an estimated 20,000 smallholder farmers concentrated in the Grand’ Anse and North departments. Production is centered around the towns of Dame Marie, Chambellan, Anse d’Hainault, Moron, and Marfranc in the Grand’ Anse, and Petit Bourg au Borgne (Ti Bouk Oboy), Grand Riviere du Nord, Acul du Nort, Port Margot, St. Raphael, Dondon, and Milot in the North. Historically, Haitian producers lacked information about local and international cacao markets, allowing buyers to set prices with no transparency. This began to change, slowly, with the establishment of cacao cooperatives, beginning in the early 1980s (IDB 2005).

By 2011, in addition to the dominant exporters – Geo Wiener S.A. in the Grand’ Anse, and Novella in the North – there were 11 cooperatives aiming to help micro-producers, in part by giving them trade outlets bypassing intermediaries and exporters who take a share of profits and erode the income potential of farmers (IFC 2011). The cooperatives listed below, were surveyed in the present research, and represent 8,237 microproducers.[iii]

Grand’ Anse

- COPCOD, in Chambellan, 196 Members. Founded in 1984

- CAUD, in Dame Marie, 771 Members. Founded in 1984

- EPDAM, in Dame Marie, 3,000 Members. Founded in 2010

- CATEPS, Anse d’Hainault, 370 Members. Founded in 1990

- ARDI, in Les Irois, 495 Members. Founded in 2004

North

- CAJBC, in La Plaine du Nord, 550 Members. Primary area of intervention is farming

- CAPD, in Le Borgne, 380 Members. Primary area of intervention is cacao

- KOTAM, in Bahon, 579 Members. Primary area of intervention is farming

- SOCAT, in Milot, 196 Members. Primary area of intervention is cacao

- CAFUPBO, in Petit Bourg au Borgne, 650 Members. Primary area of intervention, cacao

- SOCOSCOP, in La Plaine du Nord, 400 Members. Primary area of intervention, charcoal

- CAPUP, in Port Margot, 650 Members. Primary area of intervention is cacao

The introduction of cooperatives has altered the cacao value chain, or at least altered the prospects and potential (see Figure 3). However, most of production is still purchased by speculators, sometimes passing first through an itinerant intermediary (known in the Grand’ Anse as a zombie), and then sold to one of the dominant export houses. A smaller share of production goes to transformers who produce chocolate products (mostly chocolate for drinking) for sale locally or in major Haitian cities. This accounts for about 15% of production (IDB 2005). Now cooperatives provide many farmers – including those who are not cooperative members – with a third option, increasing competition and, according to some producers interviewed for the present research, forcing all purchasers to offer higher prices.

A series of investments have been made by NGOs and government agencies in the last half-century aiming to increase cacao-bean production, improve processing, and raise income levels for Haitian producers. Most of these interventions have sought to help farmers by helping cooperatives to which they belonged:

- In 1981, a program was launched establishing nurseries to distribute saplings to cacao farmers in the North and Grand’ Anse regions. The MARNDR program, later run by the Mennonite development arm MEDA, planted 21,000 hybrid seedlings (produced with seeds from the neighboring Dominican Republic, and 60,000 other seedlings in 1983 for distribution to farmers under this program. To this day, farmers in the impacted communities refer to trees planted in this era, or grafts from them, as kakawo blan, or foreign cacao. In 1983, 21,000 hybrid seedlings (produced with seeds from the neighboring Dominican Republic, and 60,000 other seedlings were planted for distribution to farmers under this program.

- ServiCoop, a marketing cooperative formed in 1997 and financed by USAID, entered into a project aiming to help producer cooperatives that were receiving training from CARE and PADF. ServiCoop purchased unfermented cacao from producer cooperatives for export to M&M Mars. ServiCoop ensured high quality, and M&M Mars offered a premium, paying the price for Sanchez-quality cacao beans from the Dominican Republic, rather than the lower price typically paid for Haitian beans. (SE/CID 1999). ServiCoop ceased to be a significant entity after USAID support ended (IDB 2005).

- After the 2010 earthquake struck Port-au-Prince and nearby towns to the west, Root Capital launched a program to aid Haitian cacao-bean farmers. A partnership between Root and CAUD, for example, offers an opportunity for change and healthy economic completion because it gives producers, through the cooperative, access to a fermenting facility and an alternative means of reaching foreign buyers.

- Agronomes et Veterinaires Sans Frontieres (AVSF) began working with FECCANO, a network of cooperatives in the North, to help the combined membership of approximately 2,000 farmers increase their income through fermentation training and implementation. FECCANO produced 25 tons of fermented cacao beans the following year using artisanal fermentation facilities. International market access was secured through a commitment from Ethiquable, a French enterprise specializing in ethical commerce, to purchase the first stock of fermented cacao for US $3,200, a 45% premium over the then-current international price. Within three years FECCANO had increased fermenting capacity to 200 tons (AVSF 2014).

- DAI partnered with MasterFoods, an M&M Mars Company, and USAID to secure a reliable source of high-quality cacao for M&M Mars. The project included the establishment of farmer field schools under an alliance with a major Haitian cacao exporter, helping 4,900 cacao farmers in the North obtain higher prices by increasing production capacity, and improving post-harvest techniques.[iv]

- The International Co-operative Alliance (ICA) and NCBA provided $298,143 for technical and business assistance to support FECCANO member cooperatives increase their cacao production capacity. The 18-month program was designed as a response to the impact of the January 2010 earthquake on agricultural production (ICA 2012). [v]

- USAID’s HIFIVE project (a five-year, $37.1 million program) provided a grant to KOFIP, a microfinance organization in northern Haiti, to provide loans to FECCANO. The loans have been used to help FECCANO cooperatives produce, buy, and ferment more cacao beans, increasing income for 1,800 members. KOFIP also has loaned money to 800 women members for processing and marketing cacao products.

- The Hillside Agriculture Project (HAP), sought to encourage and improve farming of suitable crops for hillside farms, targeting primarily mangos, coffee, and cacao beans (DAI). The project, which was financed by USAID and executed by DAI from 2000 to 2007, provided saplings and grafts to renew plantations, and institutional reinforcement for six cooperatives in the North and five in the Grand’ Anse (IDB 2005).

The impact of these projects is not clear. Critical independent evaluations are not available, if they’ve ever been conducted. Investigation we conducted in the field suggest problems. Either the projects had very little impact or some cooperative leaders are not candid about the impact. Indications of significant problems include: a) inflated membership figures given by most cooperative leaders, b) the very high numbers of members selected in the producer survey that could not be located, c) claims from most cooperative leaders of having no infrastructure when the consultants were aware that they do have some infrastructure (one also has to wonder what how effective is a cooperative that has hundreds of members, has supposedly existed for decades but yet is unable to full resources for the smallest investment in infrastructure), d) critical opinions from 22% of cooperative membership, some of whom describe their own cooperatives as useless and corrupt, the e) discovery that some “members” were added to roles without their knowledge, and f) stories of widespread embezzlement and even a case of one cooperative leader having taken personal possession of all infrastructure from a previous project—reportedly leading to donors abandonment of that project. The overall suggestion is that, by no means all, but some, if not many cooperative leaders are more focused on their own personal gain than that of the members (for details and references see the original Report Here).

Today, the traditional cacao growing regions in Haiti continue to dominate the industry, with production of as much as 5,000 metric tons a year. Typically 45 percent or more comes from the North with strong production in the Northeast and, in the south, Grand’ Anse; 18,000 hectares are planted in cacao, with cacao orchards accounting for 21 percent of the country’s agroforestry cover. Cacao is grown under partial shade (with both timber and fruit trees). Cacao plantations therefore provide vegetation cover, preventing erosion and preserving biodiversity of flora and fauna. Varieties grown in Haiti include Criollo – the most rare and prized type of cacao – as well as Trinitario and Forastero. The data described in this report offer a comprehensive picture of production levels, income from cacao, tree planting and maintenance practices, inputs, and other key factors in cacao production by members of cooperatives.

Producer Survey

Demography

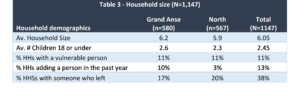

To understand the evaluation of income, work performance, and gender relations as they pertain to cacao within the household, it’s necessary to first understand the size of the household and some basic patterns regarding authority and decision making. The household sizes reported in the Grand’ Anse and North departments were nearly identical. The average size overall was 6.05 household members, with 6.2 in the Grand’ Anse and 5.9 in the North (Table 3), both significantly larger than the national average of 4.5 persons national average for both rural and urban households (EMMUS 2012). The same percentage of respondents in both regions (11%) reported having a vulnerable person in the household. There were greater percentages in both regions reporting that someone had left the household in past year, compared to those reporting that someone new had moved in. This is indicative of the urban migration underway across the country. However, the outmigration was more pronounced in the North, where only 3% of respondents said their household had added a member, compared to 20% saying someone had left the household in the past 12 months.

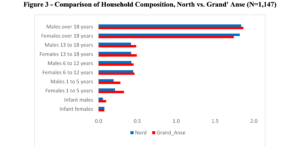

The household composition by age group was roughly the same in the Grand’ Anse and the North, with only minor differences in most age groups. Overall, respondents reported equal numbers of boys and girls among infants, children aged 1-5, 6-12, and 13-18 (Figure 2). Overall, males respondents reported more males than females in the household across adult age groups, (Figure 3).

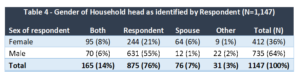

The majority of self-identified household heads were men. This group accounted for 55% of all household heads as identified in direct questioning (Table 4). Self-identified female household heads accounted for 21% of household heads overall. More women than men identified their spouse as the household head. Fourteen percent of households reported that both male and female jointly headed the household (8% reported by females, 6% reported by males). Viewed another way, 61% of respondents overall reported a male as sole household head, compared to 22% reporting a sole household head who was female.

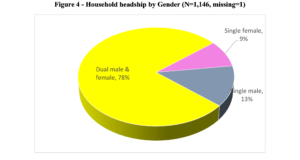

This reported household headship data differs from the existing body of research on Haitian households, which finds that women overwhelmingly shoulder responsibility for household decisions. The apparent reporting bias due to the predominantly male sample also is evident when single-headed households are separated from those in which male and female spouses are both present. Dual male and female households are the overwhelming majority (78%), while single female-headed households represent 8% of the sample, and single-male headed households 13% (Figure 4). Previous research indicates that these figures should be reversed, with typically about 8% of households headed by single males and more than 20% by single females.

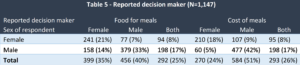

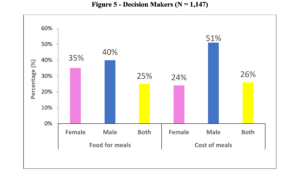

The rather strong suggestion is that, had women been interviewed we would have gotten a very different response profile. Moreover, there is the influence of different gender regimes based or differential presence of men vs. women. Where adult males are not present or scarce women take on tasks that would otherwise fall to men. Another possibility is that the surveyors had their own prejudices that influenced responses. Either way, a much better means to determine who is “head of household” is with the question, “who most often makes the household decisions regarding expenses.” This question yields more consistent results from both male and female respondents and show that women slightly more than men tend to be in charge of the household (see Table 5).

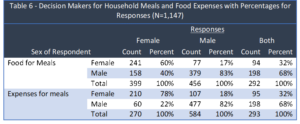

A plurality overall reported that males make decisions on food to be included in meals, while a narrow majority reported males making decisions on the cost of meals (Figure 5, Table 5). The difference was considerably less pronounced than with the direct question described above. While only 22% described the woman as the household head, 35% said she decided on the food for meals (with 40% saying that duty fell to the male) and 27% said she made decisions related to the cost of meals (with 51% saying that was done by the male) (Tables 6). As Maxon Saint-Dic, a farmer and merchant who participated in the Anse d’Hainault focus group, put it: “In Haiti, we can say that women have more monopoly power in the home.”

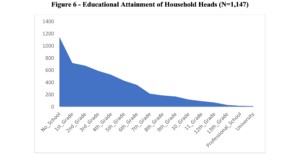

The majority of household heads had not attended school beyond the elementary level. Fewer than 200 had reached an educational level of eighth grade or beyond (Figure 6).

Gender

Gender and Marketing

Throughout Haiti women are principally responsible for marketing harvests of all crops. This is true, generally, with cacao, although the crop is exceptional in that the beans are heavy and transport to the speculator arduous, which can make it a more suitable undertaking for men. Charles Maissance (age 60, a farmer who participated in the Chambellan focus group) said that in cases of great quantities of cacao transported over great distances, the men load the beans into a basket carried by an animal. “The man does that. The wife comes along to help. Sometimes when tying the makout (woven sack) on the animal, she helps with that.” As Grande Riviere du Nord focus group respondent Syrilien Leon (age 62, a farmer with two children) said,

When you clean the cacao if it is on a mountain far away, a woman can’t do that.

However, the selling of Cacao appears, as with other crops, primarily a female activity. Several participants in the Anse d’Hainault focus group said men rarely do the selling. “It is the woman who is more likely to deliver the cacao to the scales,” one said. As Bawon focus group participant Rony Nardin (52, a farmer with seven children and 20 years in the cooperative) put it:

I don’t know about other places, but where I live it is the women who sell the cacao.

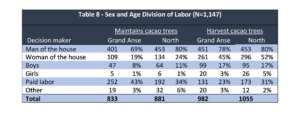

Gender and production

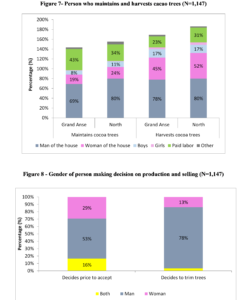

An overwhelming majority of respondents reported that men are responsible for the most of the cacao production tasks in the field (Figure 7). Sixty-nine percent of respondents in the Grand’ Anse and 80% in the North said the man of the house was responsible for maintaining cacao trees, and 78% in the Grand’ Anse and 80% in the North said he was responsible for harvesting the cacao pods. Furthermore, many respondents also said that hired laborers aid in these tasks, and focus group participants said hired labor squads were exclusively male (Figure 8). Percentages total more than 100% because respondents could name more than one type of person sharing in the tasks). In focus groups, both men and women explained that this was because tending cacao trees is physically demanding work, involving such strenuous tasks as climbing trees and hacking off branches with a machete. “To be direct, if a cacao tree is tall can a woman climb it? No, she can’t,” said Petit Bourg au Borgne focus group participant Joseph Jasmin (age 70, a farmer with seven children who has been in the cooperative for 29 years). Grande Riviere du Nord focus group participant Rosena Jardis (a 58-year-old woman, a manager with four children) said: “For me, as a woman, the only thing I can’t do in cacao is trimming, because there are branches in a bad position, I can’t climb to get them.” Some women take exception: “There is no work a man does that I can’t,” said Limanie Simon, a merchant and cacao grower in Bawon. “I plant cacao like any man, I harvest cacao, I break the pods, I dry it, I sell it. I take a machete and cut it like any man.” Anse d’Hainault focus group participant Bazelet Ylio (54, farmer and livestock producer) said:

There are two people in the house. The husband is there to work. When I’m harvesting my wife has to do the accounting.

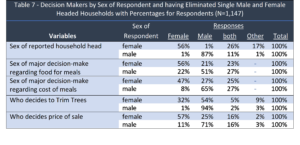

Moreover, a similar number of respondents said men are the ones responsible for making decisions on when, or whether, to trim cacao trees, and whether to sell the harvest to a particular buyer at the price offered (Figure 8). However, there were significant discrepancies in focus groups between what men said vs. what women said. Women tended to emphasize their own role in production and men theirs. As with reports on household headship, the much larger number of male respondents meant that there was evident gender bias (see below). Moreover, as mentioned above, where men are absent women in rural Haitian tend to assume tasks that would otherwise fall to the men.

These responses on gender and production, like those on household decision making outlined above, varied depending on the sex of the respondent (Table 7). Eliminating single-headed households, female and male respondents were more likely to assign both household and cacao production duties to members of their own gender. However, it is clear overall that the responses are accurate. Focus group interviews and experience on the ground indicate that the description of male production duties adhere to general patterns of sexual and age division of labor, even if a measure of bias can be expected based on the sex of the respondent and whether the couple is headed by a couple or a single adult (Table 8).

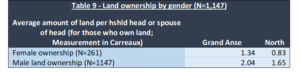

Gender and land

Most Members in both the Grand’ Anse and the North said that their cacao land was owned by the man or the household rather than the woman (Table 9). Also, the holdings of males in both regions were, on average, larger than those owned by women, even when only considering those women who own land.

Economic Status and Sources of Income

Sources of Income

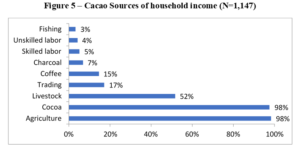

The two most important sources of income cited by survey participants overall were agriculture (involving crops other than cacao) and cacao production (see Figure 5 below). Ninety-eight percent overall listed agriculture as a main source of income, with the same percentage listing cacao. The raising of livestock was third, at 52%, followed by commerce or trading (17%), coffee cultivation (15%), charcoal production (7%), labor, and fishing trailing far behind.

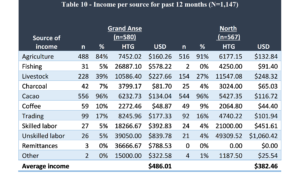

The three most frequently reported actual income sources over the past year, in both the Grand’ Anse and North, were cacao, agriculture, and livestock (Table 10). Cacao was the most common source of income reported in both regions (96% in both), followed by agriculture involving crops other than cacao (84% in the Grand’ Anse, 91% in the North), and livestock (39% in the Grand’ Anse, 27% in the North). Among those reporting average income from these sources, respondents in the Grand’ Anse reported slightly higher average income from cacao and agriculture ($134.04 and $160.26, respectively) than did their counterparts in the North ($116.72 from cacao, $132.84 from agriculture). Respondents in the North reported slightly higher livestock income, $248.32 compared to $227.66 in the Grand’ Anse. Fishing and skilled and manual labor were more lucrative income sources, but they were also considerably less common (5% reported fishing income in the Grand’ Anse, with the same percentage reporting income from skilled labor, and from unskilled labor; 0% reported fishing income in the North, while 4% reported income from skilled labor, and from unskilled labor). Income for the 16% to 17% reporting income from trading averaged $177.33 in the Grand’ Anse and $101.94 in the North. Overall average income from all sources was $486.01 in the Grand’ Anse, and $382.46 in the North.

Agricultural Production

Cacao vs. Other Crops Grown

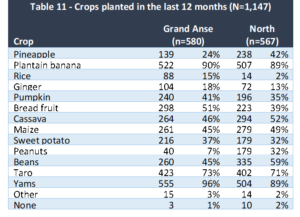

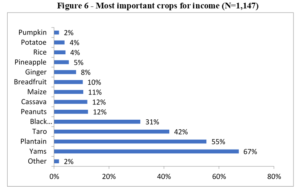

The three non-cacao crops planted the most were yams, plantains or bananas, and beans (Table 11). Yams were the most common non-cacao crop, although this varied by region, according to focus group interviews. In Anse d’Hainault, for example, ginger was cited as the next most important cash crop after cacao; in Grand Riviere du Nord, one focus group participant said pineapple was the next most important crop. This staple was grown by 96% of respondents in the Grand’ Anse, and 89% in the North. Close behind were plantains and bananas, grown by 90% in the Grand’ Anse and 89% in the North, and taro (73% in the Grand’ Anse, 71% in the North). Respondents listed yams, plantains, and taro as the most important crops for income (Figure 6; totals exceed 100% because respondents could list multiple crops).

Land Ownership

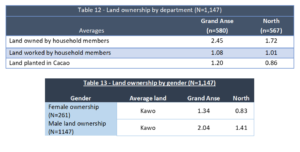

Estimates were reported in kawo (French Carreaux), a standard unit of measure familiar to farmers in the area, and equal to 3.19 acres (although land is typically sold by the centieme (kreyol = santyem, a unit equal to 1/100th of a kawo). The average respondent in the Grand’ Anse owned and worked more land (2.45 and 1.08 kawo, respectively) than did the Northern counterpart (1.72 and 1.01 kawo; see Table 12). Grand’ Anse respondents also reported having more cacao land (1.20 kawo) than respondents in the North (0.86 kawo). In both areas, men had greater average land holdings than women (Table 13).

Land Planted in Cacao

Trees

As Tables 12 and 13 (above) demonstrate, the amount of land worked by household members closely followed the amount of cacao land controlled by the family. This data reinforces testimony by focus group participants in the Grand’ Anse, who said that every farmer in the area has at least some cacao trees. This is reflected in the survey, in which 94% of respondents reported having at least some cacao trees (Figure 20), even if a minority said they did not have or work any land that they described as a cacao grove. In times of extraordinarily low cacao prices, farmers reported that some people cut down cacao trees to plant yams or other reliable crops. In some cases, farmers have reported knowing people in the past who burned cacao pods rather than bothering to transport them to a buyer, because the price was so low (Root 2014). A Dame Marie focus group participant said: “There have been people who left their pods and didn’t harvest them, left them to rot, because they they said, ‘How is it going to be useful to me?’” Dame Marie farmer Lavalas Theodore, 63, said:

There were even people who said they would cut down cacao to plant other crops because cacao was of no use to them. It was as if they were working for someone else by cleaning their cacao trees, because they got no profit from it.

Participants in all focus groups, however, expressed enthusiasm for the crop – particularly because cacao is year-round cash crop, not just in the main Easter and October cacao harvesting seasons. Focus group participants said they cultivated cacao wherever it would grow.

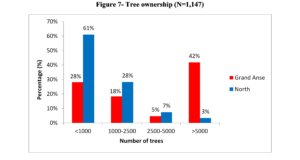

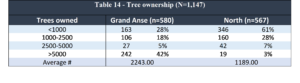

The rate of tree ownership is inconsistent between respondents in the Grand’ Anse and North. Sixty-one percent of those in the North reported having 1,000 or fewer cacao trees, compared to 28% in the Grand’ Anse; 42% in the Grand’ Anse reported having 5,000 or more cacao trees, while only 3% of those in the North reported having so many (Figure 7).

Both groups expressed a desire to possess more cacao trees. Out of the total of 1,147 overall respondents, 98% said they would like to have more cacao trees. In the Grand’ Anse, respondents’ households had an average of 2,243 cacao trees, nearly double the number reported in households in the North (1,189). Such levels of tree ownership, in theory, could allow for optimal spacing of cacao trees (with 4 meters between trees), although many informants, including an agronomist in Chambellan, said that farmers often have trees grouped too closely together for optimal yield (Table 14).

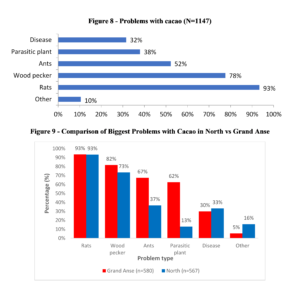

Problems with Cacao [vi]

As seen in Figure 8, the greatest problem with Cacao was overwhelmingly rats (93%), woodpeckers (78%), and then ants (52%). There are important regional differences. Respondents in the Grand Anse more often than respondents in the North reported ants and parasitic plants as problems. The figures for ants were 67% in the Gand Anse versus 37% in the North; the figures for parasitic plants were 62% in the Grand Anse vs. 13% in the North (Figure 9). Special mention should be made of ants. There is an invasion of a particular ant species that destroys crops, among them cacao pods. The invasion has occurred in both the North and the Grand Anse. It is ongoing, such that participants were able to identify particular areas where the ants had not yet reached. They could even identify streams they had not yet crossed. They ant invasion is definitively what one local called a, “fenomenon ektraoridne,” and extraordinary phenomenon. The population density of the ants is such that in area where they have invaded one needs only bend close to the ground and the ants can be found swarming. They are quite literally everywhere. Locals emphasize the invasive nature by dubbing them MINUSTAH. (Chambellan resident, Edson Florestal, 21, explained,

Now we have ants which we called “MINUSTAH” [after the UN occupation forces] –that’s how the farmers call them….They are so big.

The parasitic plant so common in the Grand Anse is called, gui. It is a climbing vine that reduces harvest and, if not removed, can kill the cacao tree. The problema is such that hurricanes are seen as beneficial in that, in addition to thinning shade trees the high winds clean the gui from the trees.

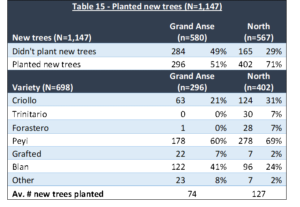

Tree Planting

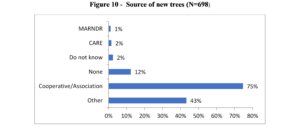

Of the farmers surveyed, 51% in the Grand’ Anse and 71% in the North said they had planted new cacao trees in the past year (Table 15). On average, Grand’ Anse respondents reported planting 74 saplings; North respondents planted an average of 127. The data suggests that farmers are interested primarily in the traditional Criollo variety. In the Grand’ Anse, 21% said they had planted Criollo trees, as did 31% of those in the North. Julmiste Baptiste, a farmer and agronomist in Grand Riviere du Nord, said in a focus group that Criollo is the preferred variety: “Because Criollo has more value, now the cooperatives have information on recognizing Criollo, which is why we only grow Criollo in our nurseries.” Very few said they had planted Trinitario or Forastero trees, although 41% in the Grand’ Anse and 24% in the North said they had planted blan or foreign trees, which focus group respondents explained were trees introduced by foreign organizations. These trees would typically have been Trinitario or Forastero varieties. Sixty percent in the Grand’ Anse and 69% in the North said they had planted cacao peyi (domestic cacao). Those in focus groups who believed they knew which official name corresponded to cacao peyi said these were actually Criollo trees. The most commonly cited source of saplings was the cooperative, which was cited by 75% of those who planted new trees (Figure 10).

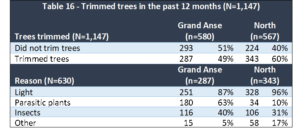

Tree Maintenance

Nearly half of respondents overall said they had not trimmed their cacao trees in the last 12 months, something focus group respondents said should ideally be done after both of the two main harvests each year. In the Grand’ Anse, only 49% said they had trimmed their trees, compared to 60% in the North (Table 16). The most common reason for trimming was to let more light into the garden (many cacao plantations in Haiti have more than the recommended 50% of shade, according to focus groups respondents. Other commonly cited reasons for tree trimming were removing parasitic plants and combating insects. The reason focus group participants cited for not trimming was money. The work is far too much for a farmer to handle alone, so those who do it have to hire an eskwad (formalized male work group) or kove (work groups of neighbors and friends) or sori (formalized female work group) – a group of men hired at a daily rate. As Chambellan resident Rosier Jean Baptiste Fenel, 58, said,

A kove, eskwad as we say, is very expensive around here. For a planter to clean an acre of cacao land he needs quite a lot of money. The rate for half a day is 200 gourdes per person and you also need to feed them. Well, sometimes a planter does not have enough money to pay for an eskwad for 10 to 15 people. That’s a lot of money.

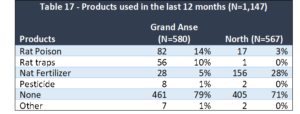

Some respondents reported using poison or traps to fight rats, which eat ripening cacao pods. Very few said they used insecticide or fertilizer, with 79% in the Grand’ Anse and 71% in the North saying they had used no poisons, traps, fertilizer, or pesticides over the last 12 months (Table 17).

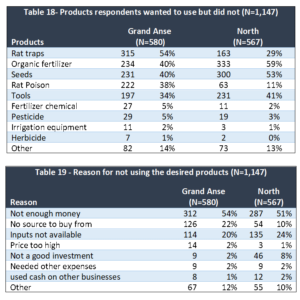

Many farmers expressed a desire to use inputs that they did without (Table 18). The most common of these were rat traps (desired by 54% in the Grand’ Anse and 29% in the North), organic fertilizer (40% in the Grand’ Anse, 59% in the North), seeds (40% Grand’ Anse, 53% North) and tools (34% Grand’ Anse, 41% North). The most common reason cited for not using these desired inputs was a lack of money needed to buy them (Table 19).

Cacao Production & Revenue

Production Increase

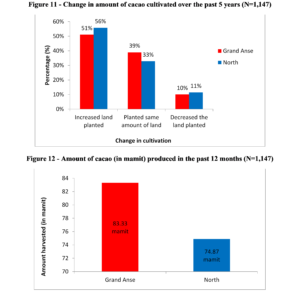

A narrow majority of respondents reported increasing the amount of cacao cultivated over the past five years. Fifty-one percent in the Grand’ Anse and 56% in the North increased the land planted in cacao, while 39% in the Grand’ Anse and 33% in the North had the same amount of land planted in cacao (Figure 11). Ten percent in the Grand’ Anse and 11% in the North decreased the land planted in cacao. Producers in the Grand’ Anse reported harvesting more cacao (an average 83.3 mamit) than their counterparts in the North (74.87 mamit) in the past 12 months (Figure 12). A mamit holds 3.08 lbs. of dried cacao; its contents weigh 4.6 lbs. if the cacao is fresh and therefore wet.

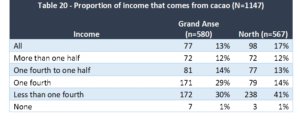

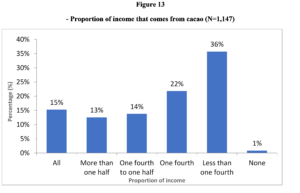

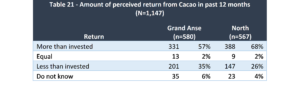

The largest number of respondents in both the Grand’ Anse and North estimated that less than one fourth of their total income came from cacao (30% in the Grand’ Anse, 41% in the North. Only 12% in both regions estimated that more than half of their income came from cacao (Table 20 and Figure 13). One reason cacao did not represent a greater share of annual income was the expense of properly maintaining cacao trees. Thirty-five percent of respondents in the Grand’ Anse and 26% in the North said they made back less money than they invested in their cacao over the past 12 months (Table 21).

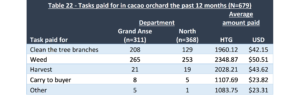

The overwhelming expense of properly caring for cacao trees explains why many farmers neglect to clean their gardens, resulting in excessive shade, trees that are too tall, and low yield due to pests, parasitic plants, improper tree spacing, and other problems. Of the 679 respondents who said they had paid laborers to help them tend to their cacao trees in the past year, 208 said they had spent an average of $42.15 on labor to clean their trees (Table 22). 265 said they had paid $50.51 for help weeding. Smaller numbers of respondents paid for help harvesting or carrying their cacao to buyers. One Anse d’Hainault focus group participant estimated that a farmer needed up to 10,000 HTG (US $222.22) to properly clean one kawo planted in cacao. These expenses must be considered against the average year’s income from cacao, cited above, of $134.04 in the Grand’ Anse and $116.72 in the North.

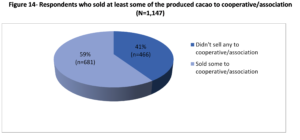

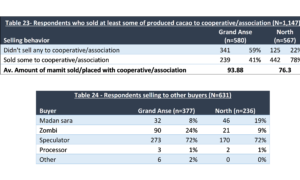

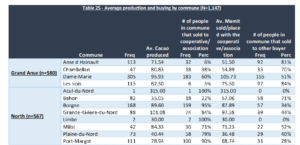

Quantity of Cacao Produce by Channel

As shown below 59% of respondents overall sold at least some of their cacao to their cooperative in the last year. Those in the North were far more likely to have sold to the cooperative than those in the Grand’ Anse, where several cooperatives purchased no cacao from their members (Figure 14, Table 23 and Table 24). Of the 631 respondents saying they sold to other buyers, the largest number (72% in both the Grand’ Anse and North) sold directly to speculators (Table 25). Twenty-four percent in the Grand’ Anse and 9% in the North sold to itinerant intermediaries (or zombies). In the North, 19% sold to large-volume market women known as Madan sara, while in the Grand’ Anse only 8% reported selling in that channel. Only 1% in both regions said they had sold directly to a processor intending to directly transform the cacao into chocolate (typically for drinking), selling much of it in Port-au-Prince. Michel Jean Daniel said during the Chambellan focus group that these buyers typically buy from speculators, not directly from farmers:

Farmers are not eager to sell their cacao to a chocolate merchant, because they don’t buy from them all the time. They usually buy during market days or sometimes during the week. Merchants know which speculator has cacao and by from him.

The most common reasons cited for selling to someone other than the cooperative were that the cooperative did not have enough money to buy, and that the other buyer offered immediate payment (Table 26). Another common reason was that other buyers accepted lower quality cacao. This is critical for farmers who grow cacao far from a cooperative that purchases fresh cacao to ferment, because many producers cannot get their cacao to fermentation facilities in time, so they must dry it themselves or sell it wet to an intermediary who will do it.

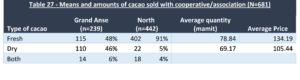

Revenue by Channel & Degree of Processing

Nearly all of the 442 respondents (91%) who reported selling cacao to their cooperative in the North sold fresh or green cacao beans, while in the Grand’ Anse only 48% sold fresh beans while 46% sold dry, and 6% sold both (see Table 27). The average price respondents received from the cooperative for a mamit of fresh or green cacao was 134.19 HTG, compared to 105.44 for dried cacao beans. Some respondents also reported selling fresh cacao to other buyers – Madan Sara, Zombi, and Speculators – although this might have been due to misreporting, as sales of fresh cacao to these buyers are rare because Speculators do not have fermentation facilities at their disposal and have to dry cacao beans if they purchase them fresh, an undesired task and risk. Those who sold to cooperatives reported getting a better average price for their fresh cacao (134.19 HTG) than reported by those selling to other buyers. Speculators, for example, paid an average of 103.45 HTG for fresh cacao.

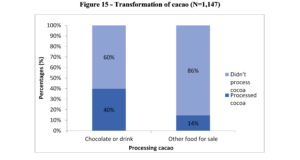

There were minor differences in the quantities and prices sold to the different types of other buyers (Table 28). The prices offered by Madan Sara, Speculators, and Cooperatives for dried cacao beans were similar (104.26 HTG, 107.81, and 105.44, respectively), while the Zombies, who typically traffic in smaller quantities of cacao and, as an intermediary, take a cut, offered slightly less (100.02 HTG). The difference between the Zombi and Speculator prices represents the Zombi’s share of the revenue. A minority of respondents processed at least some cacao to make chocolate to drink (40%) or some other cacao product to sell (14%; Figure 15). Cooperatives paid the 681 respondents reporting sales to their cooperatives 134 HTG (US $2.98) per mamit. This was roughly 30 HTG more than the other types of buyers paid for fresh cacao, as seen above.

For more about the survey and more specific data on household size, headship, decision making as well as cooperatives, their performance and what cacao growers in Haiti expect from NGOs and projects, read the whole report here.

WORKS CITED

IFC (International Finance Corporation) 2011, Integrated Economic Zones in Haiti Market Analysis December 2011

Bensen, Amanda. March 1, 2008. A Brief History of Chocolate. Smithsonian Magazine.

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/a-brief-history-of-chocolate-21860917/?no-ist

Capelle, Jan. 2008. Towards a Sustainable Cacao Chain. Oxfam International

Bourdet, Yves and Mats Lundahl. 1989. Patterns and Prospects of Haitian Primary Exports. Latin American Issues, Volume 9, 1989

http://sites.allegheny.edu/latinamericanstudies/latin-american-issues/volume-9/

Coe, Sophie D. and Michael D. 2013. The True History of Chocolate: Thames & Hudson

EMMUS-V. 2012. Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD : Macro International.

International Finance Corporation. December 2011. Market Analysis

Jean, Jean Chesnel. 2014. La filière Cacao d’Haïti : Un exemple de succès d’échanges Sud-Sud et de partenariat Nord-Sud. AVSF

Macray, Dennis. 2013. “CacaoMAP and BACP: integrating biodiversity into monitoring the sustainability of the cacao industry”. World Cacao Foundation

http://worldcacaofoundation.org/wp-content/files_mf/1383592757WCFBroulderJune2013.pdf

CAUD http://fesmar.org/en/caud-english/

Le Nouvelliste 2014 Dame-Marie fête le cacao! Le Nouvelliste | Publié le : 29 avril 2014

http://lenouvelliste.com/lenouvelliste/article/130396/Dame-Marie-fete-le-cacao.html

Pierre, Frisner. September 2005. Identification de creneaux potentiels dans les filieres rurale Haitiennes. IDB

Schwartz, Timothy and Harold Maass, 2014. Cacao Impact Evaluation Baseline. Root Capital

Stevenson, Christopher. February 2001. Training Manual for Improving Cacao Production. SECID

Trouillot, Michel Rolph State Against Nation 1990 ISBN: 0-85345-756-5 Released: January

USAID. June 2011. Success Story: Access to Credit Helps Haitian Cooperatives Triple Fair Trade Cacao Exports

NOTES

[i] International Cacao Organization http://www.icco.org/economy/production.html

[iii]https://www.wbginvestmentclimate.org/advisory-services/investment-generation/special-economic-zones/upload/IEZs-in-Haiti-Market-Analysis-English-1.pdf

[iv]DAI http://dai.com/our-work/projects/haiti%E2%80%94economic-development-sustainable-environment-deed.

[v] http://www.aciamericas.coop/Haitian-Cacao-Cooperative-to

| Table X: Problems with cacao (N=1147) | ||||

| Problem | Grand Anse (n=580) | North (n=567) | ||

| Rats | 542 | 93% | 529 | 93% |

| Wood pecker | 474 | 82% | 416 | 73% |

| Ants | 391 | 67% | 208 | 37% |

| Parasitic plant | 362 | 62% | 74 | 13% |

| Disease | 174 | 30% | 188 | 33% |

| Other | 31 | 5% | 89 | 16% |