A Brief Critique of a Very Useful Technique: the EMMA (Emergency Market Map Analysis)

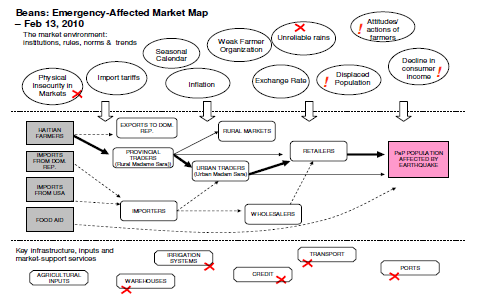

An Emergency Market Map Analysis (EMMA) is a decision making strategy that early responders use in the wake of disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes. First developed by Lili Mohiddin and Mike Albu (2008) for Oxfam, the EMMA strategy involves gathering data on specific market chains and then graphically illustrating each link, evaluating the impact on critical sectors of the chain, and identifying the most appropriate points of intervention to aid in recovery. The process is divided into three components:

- Market mapping and analysis: The creation of the visual map of the market chain

- Gap analysis: Defining household deficits before versus after disaster

- Response analysis: Determining what are the most appropriate points of intervention for relief organizations such as the GRC

The UN, major NGOs, and governmental organizations worldwide are giving the EMMA technique a special role in early disaster response. For this reason we should be especially vigilant, critical and self-reflective regarding the EMMA – and any other post disaster guidance tool – so that we can maximize the positive impact of our interventions and avoid prolonging or aggravating post-disaster economic fallout. In the endeavor to improve technique and better target future interventions, we should take prior EMMA shortcomings into consideration. An example is EMMA applications during the post-earthquake Haiti relief effort.

Teams of first responder EMMA experts working in Haiti in the months after the 2010 earthquake reported income for semi-skilled and skilled construction workers at five to seven times the going rate; they identified what are male owned gardens as “female-owned”; they put little emphasis on the local timber market, highlighting instead more expensive and less important international market chains. Such errors can have a very real impact on the entire recovery phase. In post-earthquake Haiti the EMMAs were an enduring decision-making platform for the International Rescue Committee, American Red Cross, Haitian Red Cross, and International Federation of the Red Cross, Save the Children, Mercy Corps, Oxfam GB, ACDI/VOCA, World Food Program and FEWS/NET.

Another example of a significant shortcoming with regard to post-earthquake Haiti EMMAs is Gap analysis conducted in Jacmel. Reliance on reports from interviews led an EMMA researcher to conclude that people in Jacmel suffered a 20% to 50% drop in income and a 10% to 50% drop in expenditures (Meisner et. al. 2010). This conclusion ignored impracticality of obtaining reliable income data, the massive influx post-earthquake relief in the form of remittances, aid expenditures and relief supplies, the tens of thousands of refugees in the area many of who actually attracted income and boosted the economy with their own money and expenditures, and the aid workers themselves who gave a massive economic stimulus in the form of increased transportation services, phone card sales, use of porters, and expenditures on everything from meals to rum and prostitutes. Indeed, port-earthquake Jacmel arguable experienced a prolonged economic boon on par with its annual carnival. Nevertheless, the conclusion that deficits were occurring conformed to the expectations of most newly arrived aid workers, while also conveniently jacking up demand for increased aid from locals, government officials, grassroots organizations, and the NGOs and UN agencies.

In summary, EMMA is an intuitively useful and easy to apply tool, but in the hands of people who have little understanding of the local culture or economy, or who are seeking to corroborate specific expectations, it invites problems that we should recognize and develop techniques to avoid. Specifically, the source of errors can be expected from:

– formal sector business interests: likely the source of the inflated salaries in the post-earthquake construction EMMA seen above,

– aid practitioners pressured to conform to politically correct Western NGO, UN, and activist mandates: as noble at it may be to promote aid to women, the likely reason for the identification of women, not men, as owners of bean gardens seen above,

– avoidance of stigmatized environmentally or politically incorrect industries: the likely reason for overlooking the vigorous Haitian trade in local timber seen above,

– the skewing of results – intentionally or otherwise – to make a situation appear worse than it is and thereby encourage increased aid from donors: the likely reason why the boon in the Jacmel economy was ignored in favor of demonstrating Gap deficits rather than surpluses,

Other critiques of EMMA is to lead researchers–particularly those who know little to nothing about the local culture and livelihood strategies–to overlook local materials that can be market substitutes; to overlook the significance of overlapping livelihood strategies; and to overlook that although countries like Haiti are poor and in ecological crisis, local culture is often adapted to centuries of recurrent crises and have their own mechanisms for coping with disaster, mechanisms that responsible emergency intervention specialists should try to identify and reinforce or, at the least, not disrupt and in doing so cause more post-disaster confusion, chaos or setbacks in economic recovery.

A final critique of EMMA is the Gap analysis. Gap analysis seeks to evaluate the difference in income before versus after a crisis. But many people in developing countries, particularly Haiti and particularly rural Haiti, do not think nor operate along the same continuum as developed world salary earners. The poorest of the poor in Haiti, for example, are indeed the rural populations (see Sletten and Egset’s 2004). But they are adapted to crisis. During good times, they tend not to increase spending on food but rather invest in land, crops, livestock, fishing traps, nets and boats. They buy individual trees as investments. And very importantly, they build up the marketing capital used in trading. When crisis hits, they begin a slow sell off of their goods and livestock and they begin to spend the capital used for trade.

So the post disaster “gap” tend not to be one of income but rather of assets. But finding out what people own is extremely difficult. There is a large anthropological literature on the jealousy, suspicion, and superstitious secretiveness with which peasants the world over regard their possessions and investments. Haiti is no exception, if not an extreme. Generally speaking, people living in rural Haiti would prefer their neighbors not know what they own, much less surveyors they’ve never seen before, freshly arrived from the city and asking intrusive questions about their dearly and painstakingly acquired capital and assets. All of which adds up to the fact that accurately estimating a “gap” in income is a near impossible task. Moreover, there may not even be a gap. A sell off of goods, harvest of charcoal and preparation for what peasants may expect to be a prolonged crisis could mean elevated income. Thus, the issue is not or should not be income. We know there has been a disaster. We know that people’s livelihoods have been impacted. We can usually assume that income has or will decline. And so a better use of our time and resources is to simply focus on exactly what livelihood strategies and market chains were impacted.

The logic of including other livelihood strategies – and a principal shortcoming of the EMMA – is that economies and market systems are not composed of isolated micro-cells but rather are more effectively conceptualized as part of integrated systems that influence one another. These points are especially poignant in the case of Haiti, a country that has a long history of relative isolation and a vigorous and highly integrated internal marketing system adapted to economic, environmental, and political crises.

Most of the problems identified with the EMMA strategy could be summed up as byproducts of researchers who are unfamiliar with the country and working for institutions embedded in the formal economy trying to research and assess in a couple weeks what is an overwhelmingly informal, highly complex, and poorly understood economy. The conundrum is especially applicable in the case of Haiti. In the words of Ira Lowenthal, US anthropologist, aid worker, and resident expatriate in Haiti for 40 years, “Haiti is the most studied underdeveloped country on earth; and the least understood.” (see http://fex.ennonline.net/35/emergency.aspx, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-v_ULYsYoq)

********************************

NOTES

The construction EMMA in question reported 1,500 to 2,500 gourdes per day (~U$37.50 to US$62.60) for semi-skilled workers and 2,250 to 3,250 (~US$56.25 to US$81.25) gourdes per day for skilled workers. At the time the prevailing wage in Port-au-Prince for semi-skilled construction labor was 400 to 700 (US$10 to US$17.50) and 500 to 1,000 respectively (US$12.50 to US$25.00). In the largest urban and peri-urban areas outside of Port-au-Prince, including Jacmel and Leogane, the prevailing wages for semi-skilled labor was 300 to 500 (US$7.50 to US$12.50) gourdes and skilled labor 500 to 800 gourdes (US$12.50 to US$20.00) – See International Rescue Committee et. al. 2010

In Haiti women are usually thought of as the owners of household garden produce, but if a male is present, the gardens are thought of as male property and responsibility, i.e. his contribution to the household resources. The difference is significant. Investment and maintenance of the gardens is overwhelmingly a male activity and responsibility. Misinterpreting or misrepresenting the gardens as “female owned” bias interventions toward contributions or credit to women, who would more likely not invest in productive gardens but rather commerce, their chief economic activity. (To access this particular maps see “EMMA Introduction and Overview Chapter,” page 10, http://practicalaction.org/docs/emma/EMMA-introduction-and-overview.pdf)

The EMMA only tangentially identified the local timber supplies, noting consumers in this market chain as the “poorest families,” something that ignored the thriving trade in local woods, the high quality and high demand for it among all classes in Haiti, particularly for making furniture, and overlooking the fact that international supply chains had no pre-earthquake distribution networks beyond the major urban centers. (For the map and an example of how it made it into the post-earthquake international decision making process see, Harvey and Bailey, 2011; page 26).

For the report that grossly mis-construed identifies Jacmel area as experiencing a recession, see Meisner et. al. 2010; Page 6. For the unpublished report that suggests Jacmel was experiencing an economic boon see Schwartz 2011, on this website

Most of the problems identified with the EMMA strategy could be summed up as byproducts of researchers unfamiliar with Haiti working in the interest of institutions embedded in the formal economy; and trying to research and assess in a couple weeks what is an overwhelmingly informal, highly complex, and poorly understood economy. The conundrum is especially applicable in the case of Haiti. In the words of Ira Lowenthal, US anthropologist, aid worker, and resident expatriate in Haiti for 40 years, “Haiti is the most studied underdeveloped country on earth; and the least understood.”

WORKS CITED

Humanitarian Practice Network Number 11 June 2011

IRC 2010 “The Market System for Construction Labor in Port au Prince, Haiti” International Rescue Committee (Lead), Port au Prince, Haiti February 7-17, 2010

IRC International Rescue Committee (Lead), American Red Cross, Haitian Red Cross, International Federation of the Red Cross, Save the Children, Mercy Corps, Oxfam GB, ACDI/VOCA, World Food Program and FEWS/NET.

IRC. 2010 “The Market System for Construction Labor in Port au Prince.” Haiti International Rescue Committee (Lead), American Red Cross, Haitian Red Cross, International Federation of the Red Cross, Save the Children, Mercy Corps, Oxfam GB, ACDI/VOCA, World Food Program and FEWS/NET.Port au Prince, Haiti February 7-17, 2010

Meissner, Laura The SEEP Network; Karri Goeldner Byrne, IRC Georges Pierre- Louis, ACDI/VOCA; Tim Schwartz, independent consultant; Molière Peronneau, Save the Children; and Gardy Letang of Diakonie USAID 2010 EMERGENCY MARKET MAPPING AND ANALYSIS: THE MARKET FOR AGRICULTURAL LABOR IN SUD-EST DEPARTMENT OF HAITI micro REPORT #165

Schwartz, Timothy T, Economic Impact of Haiti Earthquake on Sudest Haiti (Jacmel (http://open.salon.com/blog/timotuck/2011/04/15/economic_impact_of_haiti_earthquake_on_sudest_haiti_jacmel)

Schwartz, Timothy. 2000. “Children are the wealth of the poor:” High fertility and the organization of labor in the rural economy of Jean Rabel, Haiti. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Harvey, Paul and Sarah Bailey 2011 “Good Practice Review” Commissioned and published by the Humanitarian Practice Network at ODI Cash transfer programming in emergencies

Sletten, Pål and Willy Egset. “Poverty in Haiti.” Fafo-paper, 2004.

WFP Strategic Plan 2008 – 2013 See “Engagement in Poverty Reduction Strategies” (WFP/EB.A/2006/5-B). Oxfam International 11 April 2005 Food Aid or Hidden Dumping?: Separating Wheat from Chaff http://www.oxfam.org/en/policy/food-aid-or-hidden-dumping (accessed Novemeber 20th 2012)