There is a great deal of concern in the NGO community about violence against Haitian women. Google ‘Haiti GBV’ and you’ll see that it’s a veritable rallying cry for feminine interventions and donations. It’s always good to help people, especially those who are victims of violence. But the vast majority of people seeking to help Haitian women deal with domestic violence seem to be operating on zero ethnographic insights and data. If, as suggested, you had Googled “Haiti GBV”, you got thousands of hits for male violence against women; but nothing about female violence against other women, children or men. Zilch. Yet, anyone who has lived in a popular Haitian neighborhood, village, hamlet, or homestead for any length of time can tell you that Haitian women resort to violence as or more frequently than do men. Indeed, compared to other societies—such as popular class US, English, French or German–Haitian men are not very violent (read this). Haitian women on the other hand, are comparable warriors . Don’t believe me? Here’s a review of what others have noted, my own anecdotes from the field, and survey data.

Violent Women in Haiti: Ethnographic and Survey Data

Ethnographic Accounts of Violent Women in Haiti

Gerald Murray, arguably the greatest living Haitianist, and certainly one of the most experienced, spent two years living in a Haitian village. Here’s what Murray had to say,

Another form of intra-familial violence took the form of clashes between husbands and wives, and on at least some occasions the marchal was called on to intervene. This was especially true in those cases where the beating was done by the wife on the husband, rather than vice versa. Though most references in the literature to physical violence between spouses concern wife-beating, and though this did occur in Kinanbwa, the converse occurred more frequently, or at least received more public notice. In carrying out this, women would not use switches or straps, but would hurl large pieces of firewood or even rocks. It was such cases which motivated the intervention of the marchal, rather than the culturally more “acceptable” pattern of wife-beating by the husband. (Murray 1977, Page 173)

In my own research, over four years of following life in a rural Haitian hamlet I gave the pseudonym Makab (see Schwartz 2009), I documented seventeen violent conflicts. The most brutal beatings involved women beating men or women and men beating a man on behalf of a woman. Four of the seventeen conflicts involved men only, and five of the conflicts involved only women. In the eight remaining conflicts the principal combatants were a man and a woman. In three instances the woman was slightly injured. In one instance the fight turned into veritable battle between family compounds. In another instance a woman kicked and slapped her drunken ex-lover and physically threw him out of her house. Another incident involved a relatively weak cuckolded man who tried to beat his wife but was hit by a large stick wielded by a neighbor woman who subsequently marched the man off to the police station. In another instance a man was severely beaten and stabbed by his wife and four sisters-in-law. In another case a man struck a woman and was immediately clubbed and kicked nearly to death by about a quarter of the village population. Here are the most interesting cases, beginning with the oddest:

A very aggressive and physically ugly woman aged thirty-two had stripped naked and flaunted herself before her mother-in-law whom she was angry with for having taken a fish given to her by her son—the angry woman’s husband. Cursing and parading herself back and forth in front of her mother-in-law, the angry wife stopped, bent over and, slapping her naked buttocks, showed her anus to her offended mother-in-law. The wife’s brother-in-law—another son of the now indignant mother-in-law—had been standing by looking on and he attacked his naked, buttock slapping sister-in-law, knocking her to the ground. (The son-in-law/husband was present and also took offense to his wife’s behavior but he did not enter into the conflict, maintaining neutrality which is probably all that kept the incident from becoming a brawl between his and his wife’s family.)

In five of the cases of physical conflict in the village, several women together, or several women and men, engaged in some configuration of combat. The most severe case occurred in the house in which I had recently been staying.

The man’s name was Rimmie (not his real name), undisputedly the strongest swimmer and deepest diver in the village. The conflict began over a bicycle. Rimmie had arrived in the village riding the bicycle, which belonged to his other wife—one that did not live in Makab. Two of his daughters, aged seven and eleven, borrowed the bicycle and went for a joy ride, which ended with the seven-year-old screaming and crying with a banged knee. An aunt came along (Rimmie’s sister-in-law) and spanked both the girls. She then punctured the front tire of the bicycle with a thorn, making sure there were to be no more joy rides and undoubtedly also intending to make a statement about her feelings toward her brother-in-law’s other wife. When Rimmie discovered what had been done, a screaming and shoving match erupted between him and his tire-poking sister-in-law. Being the stronger, Rimmie pushed his sister-in-law down and jumped on top of her. Unfortunately for Rimmie, his estranged wife and three other sisters-in-law had been standing by watching. The first sister-in-law to strike was the youngest, a fourteen-year-old girl, who with both hands lifted a small boulder over her head and hurled it into Rimmie’s back. The other two sisters-in-law and the wife followed, slamming rocks into Rimmie’s back. Rimmie’s children, also witnesses to the unfolding events, danced around spastically in circles, little arms flailing, shrieking hysterically while their aunts and mother stoned their father. The sister-in-law who had originally been attacked managed to stab Rimmie in the cheek with a fork she had been holding, causing blood to pour down his face. My unfortunate friend was eventually saved by a neighbor who entered the fight and shielded Rimmie from his sisters-in-law while other neighbors pulled him to safety.

Another instance occurred on a brisk Sunday morning and it involved Pol, thirties, strong but a heavy drinker and a reputed cat burglar. (On at least two occasions while I was in the village, people awoke to find Pol tiptoeing across the floor of their thatch roofed huts and each time Pol got away by fleeing into the bush.) Pol was in a dispute with a women in her sixties, Maximine, to whom he owed money for rum he had bought from her. Maximine cursed Pol as he walked past her kitchen. Pol replied. More words were exchanged and Pol, who had been drinking kleren (rum), stepped into the kitchen and according to his subsequent assailants, slapped the older woman. It is questionable whether Pol really slapped Maximine because if he did, it was a very stupid thing to do. Pol has only one sister—she is cross eyed. His mother has mental problems, no one is sure who his father is, and Pol, by virtue of his thievery, is a near outcast in the village, albeit a tough one. In contrast, Maximine is a near matriarch. She is a mother of eight, and she lives in the middle of a cluster of houses in which also reside one of her sons and his six children, a brother in-law and his four children, a sister and her nine children, a daughter and her three children. Maximine also has a husband and two grown children living with her in her own house. And most unfortunately for Pol, one of these children, an Amazon-sized twenty-three-year-old daughter, was standing in the kitchen with her mother when Pol entered. She was pounding coffee with a pestle as big as a baseball bat and the first thing to hit Pol was reportedly that pestle. In moments, sons, nieces, nephews, grandchildren, and in-laws were kicking, pummeling, and clobbering Pol with whatever object they could find. I was not physically present and have not seen Pol since the incident, but people report he was almost killed.

One of the most interesting cases was a male versus female incident that became a small war

It began when a twenty-year-old man slapped a thirteen year-old girl, thus instigating a battle between two lakou (family compounds). The thirteen year-old girl, Little-Bridget (Ti-Brijet), was filling her water bucket at the village spigot. Hot and thirsty from a just finished soccer game, Little-Demon (Ti-Djab), the obnoxious and insolent younger brother of the buttock-slapper mentioned above, came to get a drink of water. He rudely told Little-Bridget to get out of his way, and Little-Bridget, equally infamous for being insolent, just as rudely told him no. Little-Demon slapped her, knocking her to the ground. Standing only a few feet away was Little-Bridget’s comparatively weak eighteen-year-old brother who leapt on Little-Demon, whereupon several other young men entered the fray. The fight might have passed had Little-Bridget’s mother not launched a rock into the crowd, hitting yet another young man in the face. Very coincidentally—or perhaps not so coincidentally—the young man who was hit was the deadbeat father of another of the woman’s daughters—Little-Bridget’s sister. The man had not only neglected to care for the child but shortly after its birth had brought another woman, an outsider from the island of La Tortue, into the village. The new woman was also pregnant and she died giving birth to the child. Virtually everyone who was not immediately related to or good friends with Little-Bridget’s mother agreed that she had killed her daughter’s rival with sorcery. And now, after years of hushed accusations and seething hatred, Little-Bridget’s mother had hit her estranged “son-in-law” in the face with a rock. As the people in the village said, guere pete—war exploded. The son-in-law’s family, led by three sisters—three of the same four sisters who had stoned and stabbed Rimmie above—and accompanied by four brothers, bombarded Little-Bridget, her mother, and her two brothers with rocks. Little-Bridget’s family did what they could to hold the attackers off, returning fire with stones and hurling threats of sorcery and retribution. But they eventually had to take refuge inside their house. The bombardment went on for some twenty minutes. The doors and shutters of the house were splintered by stones. The family stayed indoors that night. The next morning Little-Bridget’s mother tried to pretend as if nothing had happened, coming out of the house, sweeping the yard, and then heading over to the water spigot. No such luck. The oldest sister in the opposing family had assembled a pile of rocks and was waiting. Seeing Little-Bridget’s mother, she launched another all-out assault, hitting the older woman several times with rocks. Her sisters and brothers joined her in the attack and together they drove the entire family out of the village. Little-Bridget’s mother subsequently secured a police mandate ordering the other family to allow her and her children to live peacefully in the village, but up to this day, three years later, the family has not been able to return.

During my doctoral research, anecdotes from other long-time foreign resident of the area were similar to my own observations. Carol Anne Truelove, a missionary nurse with thirty years of experience in the region, told me about having treated three men versus one woman for severed lips, a distinctively feminine form of retribution in rural Haiti: biting her adversary on the lip in an effort to disfigure his or her face. The fights occur between women who are the lovers or spouses of a single man. But when one examines the incident closely, listens to what happened and what the women have to say, the point of contention is always, not that the man has another woman, but the division of resources or the perceived loss of money, often after an extended period of financial familial neglect on the part of the man. Even in those cases of violence not between men and women, the source of the conflict still tends to be a struggle for financial access to a man. In one of the conflicts recounted above, the fight erupted between a mother-in-law and one of her sons’ wives over the ownership of a fish the man had caught. Another fight erupted over the presence of three nubile women who were competing for the financial attentions of men in the hamlet. In all but one of the seventeen cases mentioned above, the root of the fight was a conflict between men and women over resources.

None of this is to say that men are not sometimes violent against women. In Haitian urban areas, domestic violence against women is unquestionably more widespread than the rural anecdotes I’ve share above. I believe this is a consequence of the relative absence of family—parents, brothers, sisters, uncles, and cousins—who can protect or even seek revenge for the woman. I do not believe, nor do my personal experiences suggest, that violence against women occurs in rural areas to anywhere near the same degree. Indeed, as seen, women appear more violent than men. I believe this lower occurrence of domestic violence against women is a consequence of the exact opposite conditions found in the city: (1) women have higher economic status vis-a-vis men than their urban counterparts, and (2) family members are present and they often respond to violence against their daughters, sisters, mothers, and cousins. Nevertheless, female violence in urban areas is evident in long term research conducted by other anthropologists.

Erica James (2010) who came to Haiti after the return of Aristide in 1994. Erica came to do research for her Harvard PhD in anthropology. She went to work with HRF, the Human Rights Fund that the Clinton administration created to oversee aid to Haitian rape victims. She was interested in human rights abuses, rape, beatings, torture and helping victims recover from the trauma. She worked in urban Port-au-Prince, specifically in Martissant. As time went on, James found “an increasing difficulty to discern the difference between victim and aggressor.” Of the two viktim Erica was closest to (her two assistants) one turned out to be a violent, mafia type whose sons possessed automatic firearms and collaborated with their mother to collect fees from other viktim in exchange for access to child scholarship and feeding programs. The other woman was a reputed prostitute who used drugs with her sons. When James cut the latter from the clinic roles, the woman exploded in a violent outburst followed with calculated threats against Erica’s life, threats that were convincing enough that the project supervisor suspended Erica, forbidding her to come to work until the woman had moved out of the area.

Similarly, men in rural areas who do beat their wives, and get away with it, seem to have characteristics that insulate them from retribution. Two community focus group studies revealed that men who beat their wives—and get away with it—are not your average male farmer but overwhelmingly men who have a source of income outside of the household mode of production and are wealthy compared to those around them. In one community, two of the four men who reportedly beat their wives were successful bokor (shaman), one was an employee for an international development organization and one of the wife beaters was the owner of a US$18,000.00 dump-truck—making him one the richest rural inhabitants in the commune (county). Similarly, Carol Ann Truelove, mentioned elsewhere, identified five men in her area who beat their wives. Two were bosses (skilled workers), one a schoolteacher, one was mentally ill, and only one was a farmer. In short, three of five had income derived from a source independent of the household—and one was crazy.

Other stories about domestic violence I gathered while doing research and could verify, include story of Marco and Selest, one that neatly illustrates how, when men do beat their wives, families sometimes use violence rectify the situation on behalf of the woman. They do so with the support of the legal system and women can and often are involved in the violence. Here’s the story:

Marco, thirty-two years old, and Selest, twenty-six years old, were in a plasaj union together (common-law marriage). They had two children, a seven-year-old girl and a two-year-old boy. Marco took a second wife and began to financially neglect Selest. He allocated to the new wife a garden plot that was previously for Selest. When Selest objected, he beat her. Marco’s brothers and even his father tried to intervene, talking to him, trying to get him to return the garden to Selest, but Marco ignored the advice and became increasingly abusive toward Selest, cursing her often and occasionally beating her. Selest subsequently began to have an affair with another man, Anel, and in June 1998, after a fight with Marco, Selest took the two children and went to live in a second unfinished house that Marco had been building for his new wife. In a rage, Marco beat Selest and destroyed the unfinished house, justifying his actions with the accusation of Selest’s affair with Anel. Selest went to stay with her mother and, with her family’s support, she had Marco summoned to court. In the courtroom, Marco countered that Selest’s affair with Anel sacrificed her right to the house. Selest did not deny her affair with Anel. Instead, she pointed to Marco’s financial neglect of her as a justification for adultery. Citing the importance of customary law, the judge agreed with Selest, ordered Marco to behave kindly toward his wife, to restore her gardens, to begin supporting her and the children, and he assured Selest that she had a right to live in her original house unmolested by Marco. The judge then sent the couple home to work out their differences.

Marco quit beating Selest but he continued to speak abusively to her and so one day Selest’s uncle summoned her and sent her away to Port-de-Paix to stay with a sister. Several days after Selest’s departure, Marco was coming home from the market when he was met by Selest’s younger brother, the brother’s wife, and one of Selest’s sisters. The brother greeted Marco and then struck him over the head with a club. The sisters joined in, and together they severely beat Marco with clubs. Marco’s skull was split and his collarbone and several ribs were broken. They then tied up their near comatose brother-in-law and sent for the acting local law enforcement official (the kasek) and Marco’s family.

In a clear acknowledgement of Marco’s guilt, only Marco’s father came. He made no defense for his son other than to say they should not have beaten him so badly. The brother and sisters then dropped Marco off at the local clinic. After several weeks of convalescence, Marco filed charges against his three assailants. Everyone involved in the incident was summoned to court.

The judge was unsympathetic. Citing Marco’s abuse and the lack of support from even his own family, the judge ordered the brother-in-law to pay the cost of Marco’s medical care and the case was dismissed. In the interim, Marco’s second “wife” had taken up residence with another man and Marco returned to his house where Selest was again living with their children. Thereafter, Marco reportedly behaved nicely to his wife.

Some Rare Quantitative Data on Female Violence in Haiti

Here’s what we found in a 2013, random, 1,629 household survey, with half of the respondent living in rural and semi-rural commune of Leogane (809 households) and half in heavily urbanized Carrefour (820 households).

First off, yes, men more often succeeded in beating their wives than vice versa: 11 percent of women reported hiving been beaten by a spouse or lover at least once in their lives vs 2 percent of men. But the male violence against women was not epidemic, at least not by US standards. The rate of male on female domestic violence was half that of the US average (the figures were 22% for the US versus 11% for the Haiti sample). Moreover, according to both female and male respondents, women were four times more likely to have attacked their husband in the prior 3 years than vice versa (1 percent of males verses 4 percent of females were reported to have done so). And in terms of overall aggression, of the 223 reported cases of respondents beaten as an adult, 65 (33%) of the known aggressors were women and 135 (67%) were men.

Here are some charts and tables summarizing the data.

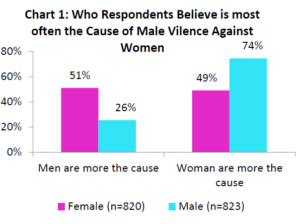

Respondent Views on Gender and Cause of Domestic Violence

We began by asking the general question who is more often the cause of violence against ‘women, men or women?’ 61% of respondents said women are more at fault. When examined by sex of respondent, men more often blamed women; the figures were 74% of men who said women were more often blame vs. 26% of men who said it was more often the man’s fault. Women were more divided: 51% vs. 49% said that men were more often the cause of violence against women (Chart 1).

Frequency of Violence and Protagonist

To measure the extent to which both men and women suffer or participate in violence we asked both males and females about violent attacks. The specific two questions we used to begin the inquiry were, “when was the last time you were beaten?” followed by, “who was the person who beat you?” We used this question because of the expediency of not having to document and clarify multiple violent incidences per respondent, i.e. it was easier to simply ask about the last violent incident. We formulated the question using the Creole word, bat, “beaten,” which is the word used in physically attacking and dominating another person. Note that unless the punishment is very severe, children are considered to be whipped (kale). The reason we posed the question in this way is to bias the respondents interest toward physical violence as an adult. We were not specifically interested in child punishment. Nevertheless, because of relatively low overall incidences of aggression we also include in the analysis the response “beaten as a child”– indicating severe corporal punishment as a child.

What we found was that in every category except the past three years men suffer more from violence than women (Table 1): men were more likely to be beaten as a child and more likely to be beaten as an adult. Note however that 58% of women and 44% of men claim to never have been beaten in their lives, even as a child. This is significantly less than reported in EMMUS studies, and the reason is likely because the EMMUS consider any corporal punishment of children, not the “bat”–beaten–seen above.

Identity and Sex of Aggressors

When we looked at who was the aggressor in violent acts (Table 2 & Chart 2), we found that 43% are women vs. 48% that are men; in 9% of reported incidents the sex of the aggressor was unknown, a side effect of not asking sex specific information for cousins and non-family. The high number of women is a reflection of their prominent role in the household and as family disciplinarian: 90% of the females identified aggressors were the respondent’s mother or grandmother (75% of male aggressors were Fathers).

Spousal Abuse/Violence Against Respondent

If we eliminate the categories for ‘beaten as a child’ and only consider the 223 reported cases of respondents beaten as an adult, 65 (33%) of the known aggressors were women and 135 (67%) were men (Table 3). Very significantly we see that 65 women were beaten by their husbands. This means that of 572 women ever in union, 65 (or 11%) had been beaten by their husbands. Not to be overlooked, of 539 men ever in union, 9 (or 2%) had been beaten by their wives.

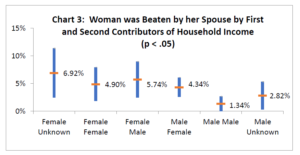

Male Spouse Violence Against Female Respondent by Female Household Financial Contributions

Chart 3 shows that, while not statistically significant given the sample size, there is nevertheless a strong suggestion that a woman is more likely to have been beaten by her husband if she is a primary or secondary contributor of household income. This seems at first to be counterintuitive. When designing the questionnaire and in discussion with CARE staff, we expected that the less a woman contributed financially to a household the more likely she would be subjected to physical violence from her spouse. In view of our finding, an alternative explanation may be that the more economically powerful a woman is the more likely she is to enter into a violent conflict with her spouse. This may be because of aggression or resentment on the part of her husband or it may be because the woman has more to defend, is more confident in because of her high economic status, and hence is more likely herself to be an aggressor; or perhaps better phrased, she is more likely to be a violent defendant or a combatant rather than a passive victim.

Spousal Violence (Against Respondent) and Degree of Urbanization

Similar to the counter intuitive finding that the more a woman contributes financially to the household the more likely she is to have been beaten by her spouse, the data suggests, contrary to expectations, that domestic violence in the city is less common than among rural couples. However, the relationship is not, given the sample size, statistically significant (Charts 4 & 5).

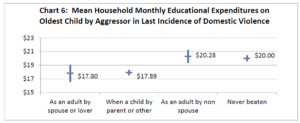

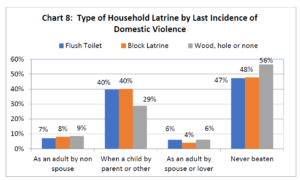

Domestic Violence Against the Respondent vs. Socio-Economic Status

In Charts 6 thru 8 we also test the correlation between domestic violence and Socio-Economic Status. In this case we included as proxy indicators of domestic violence the categories of “Beaten as Adult by Spouse or Lover,” “Beaten as Adult by Person Other than Spouse or Lover,” “Beaten as a Child,” and “Never Beaten.” As proxy measures of socio-economic status we used ,”Amount Spent per Month on Tuition for Oldest Resident Child,” as well as “Roof” and “Latrine” types. Households where no money was spent on child’s education were omitted because of the confounding factor of no children in the household.

As seen in Chart 6, people beaten by spouse or lover and people beaten as children were more likely to live in households where less money was spent on education than those people who had never been beaten or who reported being last beaten by someone other than spouse or lover. The relationship was statistically significant.

For Roof Type (Chart 7) we only tested the relationship with “Beaten by Spouse or Lover.”  We found that respondents living under a tarp were twice as likely to have been beaten by a spouse or lover as those living under a concrete roof. Those living under a tin roof were 35% more likely than those living under a concrete roof to have been beaten by a spouse or lover. Neither relationship was, given the sample size, statistically significant. This is arguably because very few people in the sample (7%) lived under tarps.

We found that respondents living under a tarp were twice as likely to have been beaten by a spouse or lover as those living under a concrete roof. Those living under a tin roof were 35% more likely than those living under a concrete roof to have been beaten by a spouse or lover. Neither relationship was, given the sample size, statistically significant. This is arguably because very few people in the sample (7%) lived under tarps.

For Latrine Type (Chart 8) we again tested all four formulated categories of domestic violence. The only relationship statistically significant is the rather quizzical finding that people with only a “hole” or “no latrine” were more likely to report never to have been beaten at all.[i]

Reasons for Violence Against Respondent

In Table 4 it can be seen that when we consider all motivations for “beatings”, the most common are economic (24%) and then jealousy (19%). If we consider only motivation for beatings as an adult (Table 5), the overwhelmingly most common motivation is jealousy (57% of cases). Very interestingly, 71% of women and 88% of men said that they deserved their last beating (Table 6 & 7).

Respondent Violence Against Others

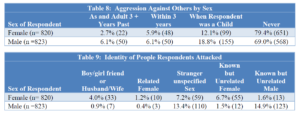

Given the scarcity of survey data on the role of popular class Haitian women as instigators and even aggressors in violent incidents, we turned the issue around and asked respondents when was the last time they attacked someone else. In posing the questions we used the colloquial phrase, denye fwa ou te bay yon moun yon kalot. In light of the cultural-specific emphasis Haitians place on the word kalot and the aggressiveness and humiliation associated with actually slapping somone, the most accurate English translation of the phrase is, “the last time you slapped the shit out of someone.” In Table 8, we see that for the category, “more than three years ago” men were twice as likely as women to have “slapped the shit of someone”: 6% of men saying that as an adult but more than 3years in the past they had slapped someone vs. 3% of women who said so. But for the past three years–the time since the earthquake–the trend changes rather dramatically. A steady 6% of males still reported having “slapped” someone in the past three years; but the same number of women, 6%, reported having “slapped” someone. In effect, the proportion of women who report having violently attacked someone since the earthquake doubled, reaching the same level of aggression as men report (to 6%). We also see in Table 9 that while only 1% of men reported aggression toward their wife or girlfriend, four times as many women report having attacked their boyfriend or husband (7 versus 33 cases); Overall, both men and women reported low incidence of violence against unknown members of the opposite sex, and men are twice as likely to have “slapped the shit” out of another man as women are to have “slapped the shit” out of another woman. The reasons behind the violence were not adequately captured in the survey.

A Word on the Violence of Haitian Compared to US Men

The 2005-6 Haitian EMMUS found that 19.3% of women interviewed had, at some point in their lives, experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of a partner. However, putting this in regional perspective, it is the second lowest rate in Latin America (PAHO 2012); and 2.8% less than the 22.1% reported in year 2000 for the United States (Tjaden and Thoennes 2000). Moreover, what we do not learn from the EMMUS interviews is what men report about female violence or to what extent women may sometimes be more accurately categorized, not as passive victims, but as combatants. The EMMUS did not interview men regarding female violence. Moreover, at least some anthropologists report that Haitian women are in fact physically assertive and as or more violent than male counterparts with respect to both other women and men.

Works Cited

Schwartz, Timothy 2000

NOTES

[i] All the preceding should be interpreted with a caveat: few respondents condoned violence against wives, girlfriends or lovers.