Edible oil is yet another area where US special interests and Haitian merchant elites have benefited greatly from US government subsidies and overseas programs. For example, although to my knowledge virtually never cited as a cause, conspiratorially minded observers might seize on the coincidence of the 1982 US sponsored eradication of the Haitian pig—which effectively ended the rural Haitian primary local source of edible oil (i.e. local pig lard)–and the rapid increase in Haiti edible oil imports that followed, much of which came from from the US, but more recently Canada and Argentina. The opportunity was also exploited by several of Haiti’s richest entrepreneurs, not least of all the man who became what some say is Haiti’s only billionaire, Gilbert Bigio, who imports tanker-loads of palm oil from Malaysia (the US cooking oil interests responded with “scientific research” showing that palm oil was deadly, something that begot a similar response from Malaysia, see this paper). Conspiracy or not, this paper examines the edible oil value chain in Haiti. The research comes from extensive literature reviews, key informant interviews, and rapid surveys I conducted while doing a consultancy for ACDI-VOCA in 2009. Those interested in the history of Haitian entrepreneurs and corporate monopoly of edible oil in Haiti should pay special attention to the endnotes.

Edible Cooking Oil Market Chain in Haiti

Consumption of Edible Oils[i]

To understand just how important the edible oil value chain is in Haiti, one must first know that edible oils are a critical component in the human diet: necessary in building cell membranes; regulating hormone, immune, cardiovascular, and reproductive systems; they also impart satiety – the feeling of satisfaction you have after eating–when fat is below 20% of total energy intake, hunger sets in more rapidly.

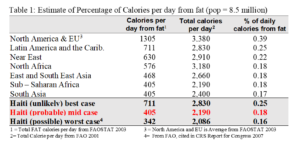

USDA recommends that daily fat/oil intake not exceed 30% and not fall below 20% of total daily calories fat.[ii] As seen in Table 1, below, low income countries tend to dip beneath the recommended minimum; given free trade and generally open imports, we can assume that Haiti is among them.[iii]

Thus, Haitian masses are best described, not as ingesting large and unhealthy quantities of vegetable oils, rather as desperately trying to get enough, an observation supported by Haitian culinary strategies.[iv]

Not only are edible oils physiologically necessary, there are other advantages. These include,

- frying at high heat kills bacteria–certainly a key factor in reducing the risk of food poisoning in the unhygienic street and market environments,

- edible oils are the most efficient means of ingesting calories: fats contain nine calories per gram vs alcohol at seven and carbohydrates at four,

- the monetary cost of fats in lower income countries is typically about half their proportionate expenditure on other foods (at 20% of total caloric intake, fats comprise about 10% of the income spent on foods in the lowest income countries).[v]

Preferred Type of Oil[vi]

There are two types of edible oil on the popular Haitian market: palm and soy oil. Cooks in the upper income level of popular Haitian “restaurants” prefer soy oil. They say that it is lighter on the stomach, li pi leje. They refer to the semi-processed palm oil sold out of drums as too heavy, luil doum pi pwes. They also find aversive the fact that it hardens, li kaye.

Those popular restaurants that fall at lower income levels use palm oil as do vendors of deep fried food. The vendors explain that processed palm oil, such as Gourmet, “yields more when it’s hot,” lè li bouyi li rann. The oil is not discarded but filtered and reused.[vii]

These observations are consistent with elite and U.S. cooking oil practices. Crisco and other shortening used for deep frying are mixed with palm oil. The justification is higher smoking points and the production of fewer harmful byproducts.[viii] [ix]

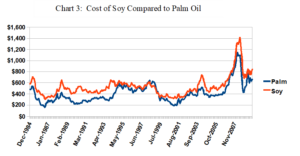

But whatever the case, in describing the consumption patterns for the great bulk of the Haitian population the best one word is price: the cheapest oils sell most, a point returned to in later shortly. But for now, it should be understood that palm oil is cheapest and it reportedly sells in the more, albeit in recent years soy has cut heavily into the market.

Sources of Edible Oils

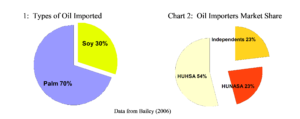

Haiti produces no edible oil.[x] Bailey (2006) reported that 65% of all oil entering Haiti in the years 2001 to 2005 was palm oil from Indonesia imported by HUHSA and HUNASA (see Charts 1 and 2).[xi]

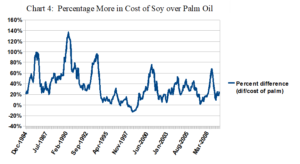

The advantage of palm oil is cost. Haitian popular preference is principally determined by price. Chart 3, below, illustrates the costs of palm versus soy oil. Because of the recent increases in costs, the differences do not appear significant. But note Chart 4, on the following page, that illustrates the percentage in terms of cost advantage for palm over soy, i.e. [(soy – palm)/palm]; the average increase in cost of soy over palm oil is 35 percent and at times has exceeded 100 percent.

Congruent with its lower per ton price, and based on reports from users and observations in the streets and markets, and reports from informants in rural areas, palm may continue to be the most abundant oil on the Haitian market. But if this is true or exactly how much palm oil is coming into the country is difficult to ascertain. If AGD (Administration Générale des Douanes) is to be believed, there is no palm oil on the Haitian market and very little oil of any kind coming from Malaysia. Their 2001 to 2009 data lists not a single shipment of palm oil. There is only one shipment from Malaysia; 521 tons of olive oil, not palm, in fy005-2006. With the exception of a small amount of peanut and a larger amount of olive oil (see Chart 5 below), all edible oil coming into APN (National Port) is, according to AGD (Port Authority), derived from soy. (not even any of the corn or canola or sunflower seed found in grocery stores).

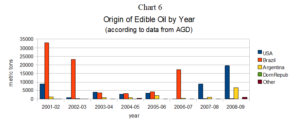

US soy oil has made major inroads in recent year. This trend is evident in Chart 6 below.

The increase in US soy oil may simply be in terms of taking market share from Argentina and Brazil, rather than the unlisted Malaysian palm oil. The same trend is occurring in the neighboring Dominican Republic where in recent years US soy oil has begun to replace soy oil from Argentina and Brazil.[xii] But note that there is a problem accepting the data, as explained in the section below.

Quantity of Oil Imported

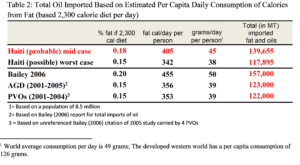

The total amount of edible oil consumed in Haiti can be estimated from data on per capita consumption seen in Section Three. Given that there is no domestic oil production, this data can be used to estimate the total amount of oil imported into the country. Table 2, below, presents this estimation and compares it to imported data estimates from elsewhere.

Using the consumption figures above and comparing them to official custom imports suggests that a great deal of imported edible oil, about 90%, is coming into the country as contraband. Note that we know that most oil comes in through Port-au-Prince because,

- the prices are lowest there,

- the major importers are able to beat any other import price.

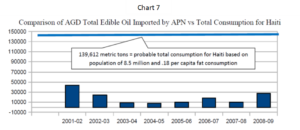

To illustrate the point note that in Cap-Haitien almost no oil comes through the port but rather is trucked in from Port-au-Prince.[xiv] Thus, we expect that data from the AGD imports into Port-au-Prince would come close to the total for the country. Bailey (2006) noted the same expectation and reported that most observer/experts estimate that 30% of all imports come through other ports or across the border. Importers and exporters I interviewed said the same. But the AGD data and what is expected from estimated total consumption in Haiti differs by a factor of fourteen. This means that there is a great deal of un taxed oil coming into the country. Chart 7, on the following page, illustrates the difference between and the total quantity expected based on consumption estimates.[xv]

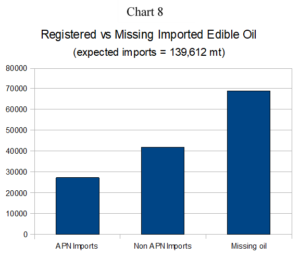

The suggestion is that there is a great deal of “missing oil.” Evading taxes is the probable reason why wholesalers are able to sell below market price. Here, in Chart 8 below, I make a comparison showing the assumed 30% that comes in through other ports and the border;[xvi] the total AGD reported imports for fy’2009— the first year, according to the AGD employee who extracted the data, that data from all other ports and the border were included.

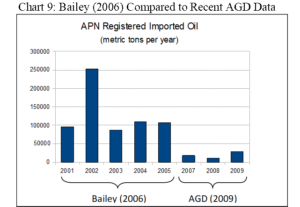

There are, however, some problems with the data. In looking at discrepancies in AGD data with respect to data from Bailey (2006) and trying to understand exactly what the data means, a perplexing trend appears. In Chart 9, below, note the inconsistencies with regard to recent data from AGD and that from Bailey for earlier years. Yet, Bailey (2006) received the data from the Commission Nationale pour la Sécurité Alimentaire (CNSA) of the GOH, which got the data from AGD itself. In other words, the data should be identical.

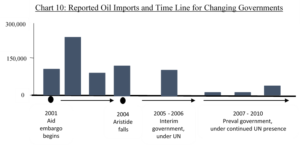

With the one exception is year 2002—inexplicably three times higher than the two years around it –Bailey’s AGD data in Chart 6.3, above, is much closer to what we expect based on annual consumption. If the data is accurate, then the decline in reported/taxed oil imports could be related to a change in politics and APN policies that led increased corruption, an expectation congruent with reports from inside observers (see Chart 10 below).

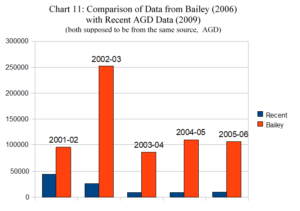

Comparing data from AGD, given for the present report, with that from Bailey for the same years, as in Chart 11 below, shows that the discrepancy exists for the same data.

This raises the question, between when Bailey got his data from CNSA in 2006 and when AGD gave it to me in December 2009, “what happened to the data?”[xvii]

Distribution

HUHSA and HUNASA are the remains of the former cooking oil consortium and widely referred to as the “oil monopoly.[xviii] In section five it was seen that Bailey (2006) cited other sources claiming that the two companies controlled 70% of the Haitian edible oil market. Of the two, HUHSA is far larger, with control of an estimated 54% of the market. The primary reason for maintenance of such a large market share is ostensibly the resources to purchase tankers of oil at optimal prices. In this section it is also seen that the two companies have extensive distribution networks, something inherited from the original Duvalier-era monopoly and that allows the companies to effectively reach central points throughout the provinces and distribute outside of Port-au-Prince, where lives the bulk of the Haitian population.

Despite the negative image, as well as attempts to pre-empt purchasing from the Dominican Republic[xix].[xx] these two companies are technically not a monopoly in that,

- there is no apparent price fixing

- new importers and redistributors freely enter the market, and

- prices are competitively low, as will be seen in the following pages

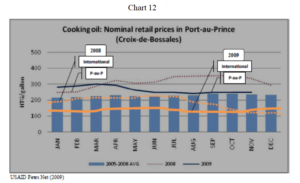

In Chart 12, below, it can be seen that prices within Haiti respond to world market prices.[xxi]

HUHSA and HUNASA as well as other importers and redistributors of oil are able to function because of informal redistribution networks. Private entrepreneurs come to pick up oil in the Capital city of Port-au-Prince. But the larger distributors, particularly HUHSA, redistribute to provincial cities where rural distributors can purchase directly from them, giving them a major advantage over competitors.

Edible Oil Market Map

A market map delineates how the components in the distribution networks are linked—called a market chain–who the stakeholders are; what variables influence cost and distribution; access to credit; ultimately explaining who is able and disposed to purchase for both resale and consumption. [Note here and in the following cost analyses that the costs of palm oil are not complete. The reason for this is that the cost of a tanker shipment from Malaysia has not been determined. Another shortcoming is that much oil is recently being shipped in through the Dominican Republic where importers report that CIF + Tax (although unverified, the oil is reportedly duty free) is less than half that of Haiti. Oil is also processed in the Dominican Republic.[xxii]

[The objective of a market map as defined by Albu and Griffith (2005) is to describe the links, processes, and influences in the market chain, from production through the various market channels; with the objective of indentifying opportunities to intervene in favor of impoverished producers. In the case of edible oil in Haiti we have a reverse situation: there is no domestic production. Thus, in the map above I have changed the objective from how to assist impoverished producers to one that highlights assisting impoverished consumers. For those familiar with the Albu and Griffith style of market map, also note that I have reversed the direction of arrows because, a) consumer vs producer role is switched and b) it is intuitively easier to read the flow of goods, credit, and infrastructural change from source to recipient– rather than the direction from which influence/determination Ironically, two factors, 1) the evasion of taxes and 2) existence of the so-called Monopoly, by virtue of its massive purchasing power, are arguably the most important variables in favor of the Haitian consumer.]

WORKS CITED

Archaeo News 2006 4,000-year-old ‘kitchen’ unearthed in Indiana

http://www.stonepages.com/news/archives/001708.html

Bailey, M., 2006 “Analysis of Market in Haiti for PL480 Title II Packaged Vegetable Oil” USAID Purchase No. 521-O-00-06-00079, August 2006

Ching, Ooi Tee (no date given) My Palm Oil http://mypalmoil.blogspot.com/2009/09/novelin-sales-to-benefit-from-koreas.html

CMA 2000 5th Minutes Annual General Meeting Caribbean Millers’ Association Held At The Renaissance Jaragua Hotel & Casinoin Santo Domingo, Dominicam Republic December 7 – 8, 2000

Kang, Jit, (no date given) Refinery of Palm Oil JitKang Lim (林日), Senior Lecturer, School of Chemical Engineering, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM). http://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/jitkangl/Index.htm

Morgan, Nancy, 1993 World vegetable oil consumption expands and diversifies Food Review, May-August, 1993

Murphy, Emmet 2009 Cost-Benefit Analysis to Monetize Title II Vegetable Oil in Haiti in FY’10 Emmet Murphy Chief of Party, ACDI/VOCA Haiti July 20, 2009

Ramesh, P. and M. Murughan, Edible oil consumption in India

Rastogi, Shweta, 2004 South East Asian Journal of Preventative Cardiology

The Nutritional Transition and Disease. Division of Foods and Nutrition, Department of Home Science, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur 302004

Soy Stats 2005 The American Soybean Association. All Rights Reserved.

Reuters 2009 China soy demand trims U.S. soy stocks-USDA 12.10.09, 01:17 PM EST http://www.forbes.com/feeds/reuters/2009/12/10/2009-12-10T181733Z_01_N10162620_RTRIDST_0_USA-AGRICULTURE-USDA-WRAPUP-3.html

WHO (2009) World Health Organization, Global and regional food consumption patterns and trends

http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/3_foodconsumption/en/index3.html

USAID 2009 Fews Net (accessed 20-12-09 http://www.fews.net/pages/marketbulletin.aspx?gb=ht&l=en

USDA 2002 Dominican Republic Exporter Guide Annual 2001 GAIN Report #DR1034 Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN Report Global Agriculture Information Network

USDA 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Chapter 6. (Accessed 18/12/09) (http://www.health.gov/DIETARYGUIDELINES/dga2005/document/html/chapter6.htm)

What’s Cooking America Types of Cooking Fats and Oils – Smoking Points of Fats and Oils http://whatscookingamerica.net/Information/CookingOilTypes.htm

Wikipedia Palm Oil http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palm_oil

NOTES

[i] The oldest evidence of the extraction of oils from plants is 4,000 years in Indiana‘s Charlestown State Park, archaeologist Bob McCullough (Archaeo News 2006)

[ii] According to the 2005 USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans, “A low intake of fats and oils (less than 20 percent of calories) increases the risk of inadequate intakes of vitamin E and of essential fatty acids and may contribute to unfavorable changes in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) blood cholesterol and triglycerides.” For children the recommendations are 25 to 35 percent.

[iii] In a WHO (2009) summary: The richer a country the more fat its people consume. Of the 24 countries found above the maximum recommendation of 35%, the majority of were in North America and Western Europe. The population of the only 19 countries on earth that consume an average of less than 15% fat in their diet were in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Much of the population of Haiti would fall in this latter group.

How FAO arrives at per capita consumption and how they arrive at recommended per diem fat consumption is beyond the scope of this report. It is be assumed that the prevailing methodologies are logical and sufficiently supported by academic research.

[iv] The best way to describe Haitian treatment of edible oil is ‘trying to inject as much oil as possible.

The standard rice, beans and meat sauce illustrates the point. Meat, such as chicken, is first boiled in water and oil; when the meat is cooked they then fry it in oil. The original water together with the vegetable oil and the animal fat is not discarded but used to boil rice and or make bean sauce. In both cases additional oil is added and before rice is completely cooked the chef will often wouzé (sprinkle) more oil on the rice, and then toufé (smoother) the rice (meaning seal the pot with a plastic bag) for the final 5 to ten minutes of cooking.

Meat sauce takes the case even farther: literally swimming in oil, Haitian sauces are best described not as meat, spices, and onions heavily embedded with oil but oil embedded as much as possible into the oil (point being that oil is the primary component)

Treatment of spaghetti also supports the point. Haitians informants consistently said, “spaghetti doesn’t like oil” (spaghetti pa reme luil). By which they mean that noodles will not absorb much oil.

Eggs are literally drenched in a soup of oil;, doe (patay), sweet potatoes, bread fruit, plantains, and pork are all deep fried in oil and are street and bus stop favorites in Haiti.

This lack of oil in the diet and attempt to inject as much as possible into food leads many observers—myself included before this research—to think that Haitians are getting too much oil in their diet. Bailey (2006:6) generalized this observation to conclude that, “Haitian cuisine traditionally makes a liberal use of cooking oil, especially for meat and fish products, well beyond the daily caloric intake requirement… as much as family income permits.” However, as stated in the text, if USAID nutritional requirements can be accepted, the impoverished Haitian masses are best described not as ingesting large and unhealthy quantities of vegetable oils, but rather as desperately trying to get enough. Short of guzzling it—something that would present other gastronomic problems—the only way to do this is to saturate foods.

In summarizing, would warrant repeating that in contrast to the caveats of other Westerners who tend to be appalled by the copious amounts of oil used in the cuisines of impoverished Haitians, most Haitians are in much greater danger of not getting enough fats and oils in their diets rather than getting too much. Atherial Schlerosis and … are afflictions developed world afflictions associated with what is called the epidemiological transition—the transition from low life expectancies where people are killed by infectious and contagious viral agents –to one where people are long-lived by plagued by chronic diseases . In Haiti heart disease… is arguably an affliction of the successful few and overweight “big men” and marchann.

[v] This observation is based on data from India. See, National Accounts Statistics, CSO: http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_cso_rept_pubn.htm

[vi] Conclusions were based in part on the small survey presented in Table ##, below, but complemented by more in depth studies at Haitian restaurants. Note the following qualifications.

- I suspect that the actual number of glos (100 ml) oil, used per godè (2 US cups) of rice and/or beans, is a culinary rule and more consistent than shown; this is supported by the facts that men, who as a cultural rule seldom cook, responded readily and gave responses in the same range as the women. The discrepancy among responses in the tale, I believe, comes from the process of explaining and getting accurate information from informants. I think, based on other qualitative interviews that it is 1 glos per 1 godé of rice and .5 gloss for beans.

- Many respondents used the designation “olive oil” (luil d’oliv) for edible oil, and in every case they were not talking about real olive oil (see endnote xi).

- I do not think that the brands people favor or the reasons why they favor them are the chief determinant what they purchase. My impression is that they favor certain brands within their price range—i.e. the lowest priced oils—and that most of their responses were ‘cliché’ rather than supported by thought out logical process. This doesn’t mean they do not have preferences. In the more in depth qualitative investigations palm came out as favored for deep frying and soy for cooking rice and beans and meat.

- Glos = 100 milliliters, godé = 0.9 lbs,

- The Creole to English designations for why individuals preferred a particular oil are as follows, “light on stomach” comes from the response lejè; “don’t like semi-processed palm oil” comes from the response pa reme doum; “taste” comes from gou; “price” comes from the responses pri and sa m jwen.

Table EN1: Amount of Oil (per glos) used in Food as Reported by Haitian Women

| number of glos of oil used

per measure of food |

Brand of Oil | Why? | ||

| 1 godé rice & 1/2 godé beans* | Meat sauce | Spaghetti

(350-400 g rams) |

||

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | luil d’oliv | – |

| 1.5 | 1 | 0.1 | Alberto, Rika. Ti Malice | Light on stomach |

| 1 | 1 | 0.5 | Rica, Bongu | Taste |

| 1 | 1 | 0.5 | Alberto | Light on stomach, low cholesterol |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | Alberto | Light on stomach |

| 1.5 | 0.5 | Crisol | Cholesterol | |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | Alberto | Don’t like semi-processed palm oil |

| 1 | 0.5 | 1 | Crisol | – |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | Ti Malice, Rika, gourmet | Cholesterol |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | Mazola | Ligh on stomach |

| 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | Price |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | Rika | no cholesterol |

| 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | luil d’oliv | Price |

| 2 | 1 | 0.5 | Rika | Taste |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | Alberto | Whatever is available |

[vii] A primer for Soy Oil comes from Morgan (1993)

The United States is a major player in world export markets for soybeans and meal, accounting for 66 percent of world trade in soybeans and 20 percent of soybean meal. But the U.S. share of world markets for soybeans and products–meal and oil–has eroded significantly since the 1970’s. While the volume of U.S. soybean and soybean meal exports remained relatively high over the 1980’s, increased competition–particularly from Brazil and Argentina–reduced the market share of both U.S. soybean and meal exports by around 16 percent. Similarly, U.S. exports of vegetable oils, mainly soybean oil, have declined substantially since the early 1980’s, dropping from 15 percent of the world market in 1978 to an estimated 6 percent in marketing year 1993/94.

See also Reuters (2009)

[viii] A primer for Palm Oil comes from Wikipedia, below,

Since the turn of the century, palm oil is increasingly incorporated into the global commercial food industry because it remains stable when deep fried or baked in extreme high heat and for its high levels of natural antioxidants. Malaysia and Indonesia produce about 85 percent of world supplies of palm oil and account for the bulk of the global exports.

Health concerns about the high level of saturated fat have caused the United States to reduce imports of palm oil. Allegations that tropical oils (such as palm) are detrimental to health resulted in numerous U.S. food companies replacing tropical oils in their products. U.S. imports of palm oil dropped from a high of 277,000 tons in 1985 to an estimated 105,000 tons in 1992/93. The EC continues to be the major importer of palm oil.

However, developing countries are hampered by foreign exchange constraints and thus continue to buy palm oil, which is less expensive. Consequently, palm oil’s market share has expanded from 26 percent of total world vegetable oil exports in 1975 to over 40 percent in 1992/93.

Despite this, perhaps all is not as it seems. From Ooi Tee Ching (2009):

A 2001 parallel review of 20-year dietary fat studies in the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Spain. concluded that polyunsaturated oils like soya, canola, sunflower and corn degrade easily to toxic compounds when heated up. Prolonged consumption of burnt oils lead to atherosclerosis, inflammatory joint disease and development of birth defects.

Also,from Jit Kang (no data provided)

Palmitic acid does not behave like other saturated fats, and is neutral on cholesterol levels because it is equally distributed among the three “arms” of the triglyceride molecule. Studies have indicated that palm oil consumption reduces blood cholesterol when compared to other sources of saturated fats like coconut oil, dairy and animal fats. Also, palm oil can withstand high heat without smoking and resists oxidation (which contributes to a 4longer shelf-life with no change in color or odor).

[ix] Oils high in polyunsaturated fats, such as soy, are typically preferred as food additives and in sauces; those high in saturated fats such as palm and coconut oil are preferred for frying. Conventional wisdom is that the former tend to breakdown more quickly when exposed to high heat yielding undesirable, including carcinogenic, byproducts. But note the following from What’s Cooking America,

Oils that are suitable for high-temperature frying (above 230 °C/446 °F) because of their high smoke point include:

Canola oil (marketed as “rapeseed oil”)

Corn oil

Mustard oil

Olive oil, pomace

Olive oil, extra light

Palm oil

Peanut oil (marketed as “groundnut oil” in the UK)

Rice bran oil

Safflower oil

Sesame oil (semi-refined)

Soybean oil

Sunflower oil

Oils suitable for medium-temperature frying (above 190 °C/374 °F) include:

Almond oil

Ghee, Clarified Butter

Cottonseed oil`

Grape seed oil

Lard

Olive oil (Virgin, and refined)

Walnut oil

Mustard oil

[x] Bailey (2006) says, “the animal substitute that used to exist in the rural areas up to the Swine Eradication Program of the late ‘70s, has never recovered.” He also notes that up until the 1970’s, coconut oil was produced domestically in rural areas but not for sale.

In my own research people have talked about how the native Caribbean olive was used to make oil. Interesting many respondents in the surveys called edible oil, “luil d’olv.” This designation has nothing to do with whether the oil is truly from olives and might a) reflect the fact that the Caribbean Olive may have been widely used source of cooking oil and b) explains why ‘luil d’oil” appears so often on APN manifests, i.e. the customs agents are simply using the Creole term for edible oil. Coconut is probably the most significant source of fat and edible oil for the peasants, but to my knowledge none actually process it, rather they consume the coconut meat and they press it into coffee.

[xi] See, World Vegetable Oil Consumption 2004. Soy Stats 2005 The American Soybean Association.

[xii] USDA’s Gain report for the 2001 does not even mention the US as a source of oil in the Dominican market; yet a look at current shelves in the DR suggests a major presence.

[xiii] World average consumption per day is 49 grams; The developed western world has a per capita consumption of 126 grams.

[xiv] The observation that little to no oil comes into the Cape Haitian port comes from people working at the port , executives at the largest import company in Cape Haitian, and manifests—for whatever they are worth. The point is that despite being closer to Miami and having large and well maintained port facilities, Cape Haitian is not able to compete with P-au-P in the edible oil market. This is because, a) P-au-P merchants are purchasing large tankers of oil at wholesale commodity prices and/or b) Cape Haitian authorities are stricter in applying and collecting taxes

(or payoffs). Also interesting in this respect is that during the commodities price crunch of 2008, of all non-P-au-P ports and cities, Cape Haitian experienced the highest rise in prices (see Chart ## on page).

[xv] The absurdity of the AGD data is clear if we revert to a comparison of per capita fat consumption, a level that in only 19 countries on earth dips below 15%.

Table EN2: AGD data in lieu of recommended daily allowance of fats and oils

| Year | Total Imports | Kilograms

yr/person |

Grams

day/person |

Cal

day/person |

% fat

person/day |

| 2001-02 | 43247 | 5.09 | 13.94 | 125.45 | 0.05 |

| 2002-03 | 24845 | 2.92 | 8.01 | 72.07 | 0.03 |

| 2003-04 | 8834 | 1.04 | 2.85 | 25.63 | 0.01 |

| 2004-05 | 7838 | 0.92 | 2.53 | 22.74 | 0.01 |

| 2005-06 | 9890 | 1.16 | 3.19 | 28.69 | 0.01 |

| 2006-07 | 17872 | 2.1 | 5.76 | 51.84 | 0.02 |

| 2007-08 | 10286 | 1.21 | 3.32 | 29.84 | 0.01 |

| 2008-09 | 27614 | 3.25 | 8.9 | 80.11 | 0.03 |

[xvi] The estimate that 30% of all contraband and imports comes through non-P-au-P channels qualifies as a rule of thumb among importers.

[xvii] There is the possibility that AGD has done something unknown to the data, or that I am simply misinterpreting it. One prospect considered is that the data should somehow be multiplied by ten. That would put some estimates closer to expected levels (specifically, 2001, 2003) but others absurdly out of range. Another possibility is that Bailey was multiplying by an unnecessary factor of ten; that would put all the data in the very low range, make it more consistent with the data that AGD gave me, and explain the nearly impossible high 252,159 metric tons in 2002. The fact remains however, that Bailey’s data is much closer to what should be the case.

[xviii] As I pieced the story together from informants, internet articles, and Bailey (2006): Gilbert Bigio founded HUHSA in 1981. Haitian born son of a Jewish immigrant from Lebanon, and subsequently Israel consulate in Haiti, he gained favor with the GOH by brokering arms sales with Israel. In 1981, under then dictator Jean Claude (Baby Doc) Duvalier, he was granted the oil monopoly. From HUHSA webpage,

Huileries Haïtiennes, S.A. (HUHSA) was founded in 1981 as an edible oil processing plant [then it was called SODEXOL]. Through experienced sales staff and national distribution, HUHSA has grown steadily and is today the leader in the edible oil market in Haiti.

To address all sectors of the market, the company sells in bulk containers as well as in smaller, consumer sized packaging. Product is distributed nationally through a well-defined transportation network, delivering within 24 hours of order placement.

HUHSA constantly strives to win the dedication and respect of the Haitian consumer. Its long-standing position within the Haitian community has earned it the recognition as one of Haiti’s largest and most well run consumer products companies.

As the story goes, several years after gaining the Oil monopoly, Bigio sold it for a rumored 36 million dollars. He recently bought HUHSA back and has become the dominant figure in what, after the fall of Duvalier, was a consortium. From Bailey (2006),

After the demise in 1986 of SODEXOL, a Haitian monopoly backed by Israeli interests that used to process bulk imports of crude degummed and semi-refined soybean oils for local distribution, a consortium emerged made up of the three other bottlers of bulk cooking oil: the Brandt Group (USMAN-Usine à Mantègue S.A.), the Madsen/Verway Group (HUNASA – Huilerie Nationale, S. A.), and Jean ACKMED Enterprises. A few years later, the consortium was rejoined by the Haitian portion of the defunct SODEXOL, the BIGIO/BEYDA Group, under the newly created Huileries Haitiennes, S.A. (HUHSA) denomination, while Jean Ackmed retired from the cooking oil activity.

[xix] While I could not verify the details or that it even occurred, several informants in both the Dominican Republic and Haiti mentioned a lawsuit against HUHSA/Bigio and/or against the Dominican edible oil monopoly Mercasid. As the story goes, Gilbert Bigio, owner of HUHSA, paid five million dollars to Mercasid for the exclusive right to purchase oil. The intent was not to buy oil from the Dominican company but to pre-empt others from buying it. There was, apparently, a lawsuit against Mercasid and the exclusive was rescinded. Currently Lakay oil is processed in Santiago, DR by Fabril S.A (also by MERCASID); Bongu oil from Argentina is processed there as well.

Note with respect to this that it is reportedly US$1,000 per container less expensive to import through to the Dominican Republic than to Haiti; largely because of the taxes, there are none. Bailey too mentions the significance of the less expensive oil from the DR and reports that the Haitian government responded by taxing the oil.

As a case in point, measures put in place in January 2006 in the border town of Malpasse to properly enforce the collection of customs duties on imports from the Dominican Republic had increased revenues fourfold by the month of May. In response, charging “excessive taxation”, the Truckers Union and interested groups in that area have staged a strike which has incapacitated trade between the two countries since mid-July 2006 and significantly affected the level of GOH revenues. A major trader in the Belladère area, another border town north of Malpasse, indicated that the brisk import of CRISOL has stopped since the Haitian authorities started to impose “abusive taxes”. [Bailey 2006:5]

The Dominican monopoly, like it’s Haitian counterpart was patronage from the then dictator, in this case Ralph Leonidos Trujillo. Note that it began as a buyer of peanuts from Dominican farmers. The peanuts were converted to oil and the oil sold to the Dominican population. With the decline of the dictatorship, subsequent invasion and occupation of the Dominican Republic by the United States military, the monopoly moved from one that purchased and processed the raw products to one that primarily redistributed and/or processed imported products. A synopsis of the history of the Dominican cooking oil monopoly comes from ##www.mercasid.com.do

Sociedad Industrial Dominicana, C. por A., was founded in the city of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on July 1, 1937 by Jesús Armenteros Seisdedos and José María Bonetti Burgos, as a company committed to producing cooking vegetable oils.

Through the years, La Manicera, as it more commonly become known, began to expand the array of products it offered the Dominican consumer, introducing to the market new varieties of oils, margarines and detergents. On June 1, 1971 it signs with Unilever Export Limited an Agreement of Technical Assistance and Distribution (Royalty Agreement) and in the decade of the 1980s it begins developing agro industrial projects with oil palms, flowers and citric fruits.

In the commercial realm, SID becomes during in the 90s a distributor for the Dominican Republic of renown brands such as Kellogg’s, Kimberly Clark, Hershey’s, Eridania-Behim Say (Koipe), Haagen Dazs, General Mills, Novartis, among others.

In 1999 SID merges with another large Dominican food producing company, Mercalia, S.A., and thus MERCASID, S.A. is born.

NOTES

[xxii] Little support for the suggestion that edible oil is cheaper in the DR comes from shelf price. The cost to a Haitian importer, who pays taxes, for a gallon of oil is US$4.35. The shelf price in DR redistribution at the bottom end of the wholesaling chain is US$6.25, 48% more. Indeed, the sale prices for edible oil on both sides of the island, in general, are identical.