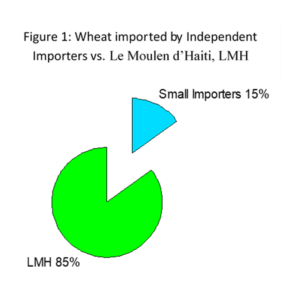

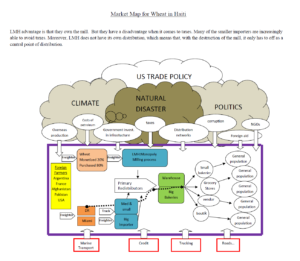

Although largely ignored in terms of impact on local production, wheat imports have had as great an impact undermining the Haitian local agricultural economy as rice. Unlike rice, Haiti grows no wheat, but thanks to a US subsidized mill through which passes 85 percent of all wheat entering Haiti and an annual importation of more than 345,000 metric tons of US subsidized wheat, the country consumes 75 lbs. of wheat per capita per year. That’s just shy of ¼ pound of wheat every day for every man, woman, child and baby in the country. By comparison, Haitians consumed about 100 lbs. of rice per capita in 2011; 25 percent of that was grown locally (see USDA 2016). This paper explores the history of wheat imports in Haiti and defines the wheat market chain. The research is based on a review of the literature and a 2010 consultancy on behalf of World Vision and USAID during which I visited several dozen bakeries and interviewed major stakeholders, including directors of the mill (Le Moulen d’Haiti, LMH), USAID Food for Peace Officer as well as other USAID staff, and directors of the Haitian Bureau du Monetization (BDM),

Wheat Market Chain in Haiti

History of Wheat Flour in Haiti and LMH

Studies of nutrition in Haiti prior to the founding of the Minoterie d’Haiti (the contemporary Le Moulen d’Haiti, LMH), suggest that wheat flour was rare in Haiti, particularly in rural areas (Bernadotte et. al). The 1958 establishment under the first Duvalier regime of the Minoterie, a government monopoly, changed that. A team of Columbian nutritionists wrote in 1963,

Although no wheat is produced in Haiti, white wheat bread is a preferred item and is eaten whenever it can be obtained. The construction of a large flour mill in 1958, where imported wheat could be milled, made white wheat flour available in Haitian cities, but the Haitian peasant obtains little white wheatbread because of lack of money, fuel and baking facilities. [King et. Al., 1963]

Although data was not readily available, it is known anecdotally that throughout the Duvalier era, the mill processed wheat for human and animal consumption and sold it on the open market. During the 1991 to 1994 military regime the Minoterie was reportedly under control of Colonel Michel Francois (Haiti Progres 1997). In 1998, under the first Preval regime and in a move that enraged both political leftists and conservative importers, the Mill was privatized and a new monopoly formed, one comprised of Unibank (owned by a consortium of Haitian financiers), the Haitian Government) and two of the United States largest Agribusinesses.[i]

In a move that further enraged both political leftists and conservative importers, the U.S. government represented by NGOs and USAID, have since developed a policy of selling high quality wheat to the mill monopoly at a reported 70% of cost, a clear and inexplicable violation of U.S. monetization policy.[ii] The flour mill was privatized in 1997 amid a flourish of political turbulence, including the resignation of the Prime Minister who was protesting delays in the promised privatization of some 36 State owned enterprises. In a process that Haiti Progress called “no transparency at all,” seventy percent interest in the mill was sold for US$9 million to a consortium of venture capitalists; specifically, Haitian finance group, Unifinance—comprised of some of Haiti’s wealthiest elite–and two “mega-agribusinesses,” Continental Grains, and Seaboard Corporation of the United States. The actual sale occurred three days before then US secretary of State, Madelaine Albright visited Haiti. The mill was insured by OPIC and proved to be an immediate bonanza. Mill executive David Daines described the consortium’s great fortune as early as 2000 when in a meeting of the Caribbean Millers Association,

He observed that the market in Haiti is a big one by Caribbean standards. There are about 7 million people and the mill grinds about 200,000 metric tonnes of wheat per year.

Flour, as compared to other food stuffs is declining in price but the market in Haiti has expanded far beyond expectations. There is need for expansion of the flour mill which is now operating at 650 tonnes per day, but that they expected to achieve 750 M.T. by March. He said the mill would need another 100 tonnes capacity to fully supply the market. He also observed that the bran market had increased. He said although there had been some imports, primarily from the Dominican Republic, the market was large enough to absorb this.

The mill also produces animal feed. Mr. Daines said that the year commenced with a basic livestock feed mix of soybean, corn, vitamin, mineral and bran. [see Daines, 2000]

With a 2009 production and sale of 300,000 fifty-kg sacks per month (16,500 MT) the LMH monopoly currently controlled 85% of the market (19,412 MT).

Prior to the 2010 earthquake there was an increase in the importati on of flour by medium level importers. This is involved increased importation of flour from the Dominican Republic—particularly in the North–as well as corruption in the ports and evasion of taxes, something foreseen by the Mill Monopoly as a primary impediment to success of the venture (see Haiti Progres 1997) and a trend seen in the surge in 2008 oil sales and prices (see endnote).[iii]

on of flour by medium level importers. This is involved increased importation of flour from the Dominican Republic—particularly in the North–as well as corruption in the ports and evasion of taxes, something foreseen by the Mill Monopoly as a primary impediment to success of the venture (see Haiti Progres 1997) and a trend seen in the surge in 2008 oil sales and prices (see endnote).[iii]

Contemporary Consumption of Wheat Flour in Haiti

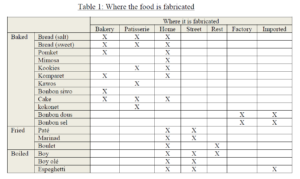

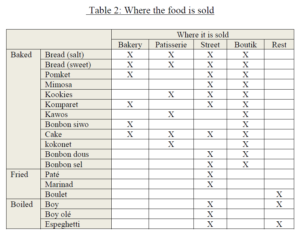

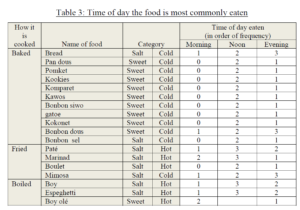

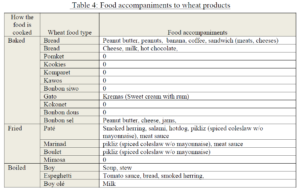

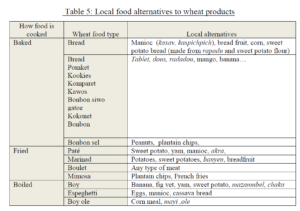

Wheat products are common in contemporary Haiti (Table 1). Bakeries can be found throughout the rural areas and urban bidonville. Ambulant vendors sell a multitude of bread types street. Other common wheat flour foods that vendors sell on the street are patay and marinad, both deep fried. Home and restaurant use of flour is dumplings, called boy in Haiti; they are long, resembling plantains and green bananas that commonly accompany them in soup and bouyon (pumpkin stew). The tables below summarize what wheat products are made in Haiti, where they are made (Table 1), where they are sold (Table 2), the time of day they are eaten (Table 3), what they are eaten with (Table 4), and the alternative local foods that can or are eaten in their stead (Table 5).

Alternative food

Importers of subsidized US wheat should appreciate that Haiti produces substitutes to wheat flour and that the introduction of U.S. subsidized wheat debilitates the Haitian farm economy, Consider that the wholesale cost of flour coming from LMH is US$100,800,000 per year in 2009. Promoting the production and marketing of produce such as those below (a by no means exhaustive exposé) would help develop the Haitian economy.

For data on costs of importing, taxes, and impact on prices of the 2010 earthquake read this.

Works Cited

Bernadotte, J., Foijgere, W. , Barron, G. P. Nicolas, G. , King, K. W. , Brinkman, G. L And French, C. E. 1959. Appraisal of nutrition in Haiti. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 7: 1.

Daines, David. 2000. 5th Annual General Meeting Caribbean Millers’ Association Held At The Renaissance Jaragua Hotel & Casino In Santo Domingo, Dominicam Republic December 7 – 8, 2000

Haiti Progres 1997. Moulin d’Haiti Behind the sale of the flour millThis Week in Haiti, Vol. 15, no. 34, 12-18 November

http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/43a/220.html

King ,Kendall W., Ph.D., W. H. Sebrell, Jr., M.D.T Elmer L. Severinghaus, M.D1 And Waldemar 0. Storvick, Ph.D.,I With The Cooperation Of Jean Bernadotte, M.D., Hubert Delva, M.D., William Fougere, M.D., Jean Foucald, B.Ph. And Ferdinand Vital

1963 Lysine Fortification of Wheat Bread Fed to Haitian School Children From the Institute of Nutrition Sciences, School of Public Health and Administrative Medicine, Columbia University, New York, New York. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 36 Vol. 12, January

UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT BUREAU FOR Democracy, Conflict & Humanitarian Assistance 80 TITLE II PROGRAM POLICIES AND PROPOSAL GUIDELINES FISCAL YEAR 2008

USDA 2016 Haiti’s U.S. Rice Imports. By Cochrane, Nancy, Nathan Childs and Stacey Rosen. A Report from the Economic Research Service.

NOTES

[i] More information on the alleged big business and corporate charity aspects of LMH come from Haiti Progres (1997). The following are excerpts provided here for anyone interested in the fairness of U.S. montetization policies:

Continental Grains, which did US$15 billion in sales last year and is into wheat, rice, chickens, finances and a host of other activities in over 50 countries, and Seabord Corporation, which has boats, flour, pork, chicken, etc, and did almost US$1.5 billion in business last year -got a great deal. There is no question who is running the consortium which gets the 70 percent in exchange for promising to invest US$9 million in the mill. (The state retains 30 percent.)

In the meantime, it is worth pondering why two of the biggest agribusinesses in the US wanted to get into Haiti. There is certainly money to be made in this captive market. Flour is an essential part of the Haitian diet, and with control of the agribusinesses in the US, the shipping, and the milling, Haiti’s flour supply has become more of a monopoly than it ever was, only this time in the hands of two transnationals.

But that might not be all. Having Minoterie gives the transnationals a foot in a potential market of 7 million consumers for all the other products they produce, ship and market. In addition to rice, chicken, soy beans, shrimp, cotton, beans and other commodities, both of them are growing producers and exporters of pork, the most-consumed meat in the world and a quickly expanding new US food export, according to a 1966 article in the Kansas City Star. In 1995, for the first time in 44 years, the US became a pork exporter. The top ten producers (Continental is 12th) raised 23 million hogs that year. [Seaboard has since become one of the top five]

What does all that mean for Haiti, where pork is one of the main meats consumed? Currently, some pork is imported and the rest comes from medium-sized as well as individual producers. (The peasants’ kochon kreyol were killed off in the late 1980s’ in a USAID-sponsored eradication program after an African Swine Fever outbreak.) Under the new, neoliberal tariff regime, there is nothing to protect local pork from mass-produced competition, and with a wharf, the boats and the space for a distribution center on Rte. 1, the corporations are now in a very good position to break into at least the pork if not other markets as well.

The privatization of Minoterie d’Haiti offers clear examples of who benefits and who loses from privatization: In this case, the people were robbed of a valuable state asset; the supply of a major food item will be in the hands of vertically integrated transnationals whose only motive is profit and who will have an objective monopoly, and, they are also poised to threaten the country’s production of other food products by exposing them directly to the competition engendered by voracious and brutal international capitalism.

[see Haiti Progres 1997]

[ii] The following was taken from, United States Agency For International Development Bureau For Democracy, Conflict & Humanitarian Assistance 80 Title II Program Policies and Proposal Guidelines Fiscal Year 2008,

Lines 1625 – 1632

Regarding cost recovery requirement for monetization, CSs are expected to receive a “Reasonable Market Price” for the sale of the Title II commodities. … In markets in which significant market interferences, including government interventions, preclude the usefulness of the local prices as reasonable reference, other price discovery methods may be used, including public tender, construction of import parity prices and auctions.

Lines 1634 – 1637

Where market forces cannot be harnessed to transparently formulate a reasonable market price (as above), and negotiated/treaty sales are required, a sales price which compares favorably with the lowest landed price or parity price for the same or comparable commodity from competing suppliers may be considered a reasonable market price

Lines 1464 – 1469

For multi-year programs, FFP must take into account the mandate that states, of the non-emergency tonnage (including both direct distribution and monetization commodities), seventy-five percent of it must be processed, fortified or bagged. FFP has developed a “Value-Added Commodities List” of processed, fortified and bagged commodities that it has determined meet this statutory requirement (see Annex E—it’s on the list). Proposals with a higher proportion of processed, fortified or bagged commodities may be given priority.

Lines 1594-1597

The monetization of value-added commodities, i.e., processed, fortified, or bagged commodities, is preferred to the monetization of bulk commodities because FFP is required to meet the statutory requirement that 75 percent of the programmed commodities be processed, bagged or fortified for non-emergency programs.