This paper focuses on egg production in Haiti with an emphasis on popular class rural household livelihood strategies. Data is drawn from a review of the literature and contact with farmers, entrepreneurs, merchants, cooperative leaders, and two surveys: a 382 household “Chicken Survey” and a follow-up telephone sub-survey of 91 of the original respondents. Constraints to egg production at the level of rural household has to do first with the strategies that farmers utilize to survive. Most depend on a mixture of technologically simple livelihood strategies exercised under the tenet of “minimum investment and minimum risk.” For poultry this means free ranging the birds, feeding them only enough that they stay near the homestead, not vaccinating, providing any supplements or treating the birds when ill. Consequently disease and predators take a heavy toll on flocks: 81% of respondents in the Chicken Survey had lost their flock within the past year. A limitation on flock size inherent in free-ranging is ecological carrying capacity, i.e. the limited number of bugs and edible plants per unit area. Constraints on egg production within the free ranging system include the pecking order; chickens do not readily accept other birds not reared with the flock and protected by a mother hen. This puts a premium on “brooding,” 77% of respondents preferred hens that are broody vs good layers. When hens brood they stop laying eggs. Because of these constraints, free-ranged chickens annually produce only 14 eggs per hen per year in Haiti, most of which are not destined for the market. In comparison, an industrial layer can produce 300 eggs per year. Only 13% of respondents cited egg production as a primary reason for raising chickens. Most poultry and egg projects in rural Haiti have failed. Those that succeed appear to be heavily subsidized by NGOs, church congregations, or obscure state investors. Others are arguably more about getting donations and support than about producing for the market (see this book and this one).

Chicken & Egg (Poultry) Ethnographic Value Chain in Haiti

Chickens and Eggs on the Family Farm

Ninety percent of Haitian national livestock production comes from some 800,000 small family farms. With an average holding of only 1 hectare, in 2012 MARNDR estimated that together they owned 1 million pigs, 1.5 million cattle, 2.5 million goats and 4.8 million foul, the vast majority of which are chickens. Another 1.6 million chickens are raised in urban environments (Politique de Développement Agricole 2010-2015; LAREHDO).[i]

According to MARNDR (2012) the average rural household has 5 hens and produces 70 eggs per year; that’s 14 per hen (by comparison, layers on industrial poultry farms produce 285 eggs per hen per year). This translates to 5.5 million eggs per month; 70% of the eggs are destined to hatch and the remaining 30% destined for consumption. Of those eggs consumed, ~75% will go to the market and ~25% will be consumed by the household. Elsewhere it is estimated that some 30% are given away as gifts to neighbors and friends. Three of every 12 eggs is of unacceptable quality, either because it has spoiled, is vitamin and mineral deficient, or because the hen is old and beyond the age of laying eggs that have consistent yolk and white.

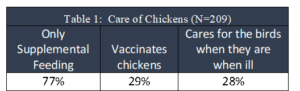

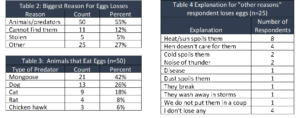

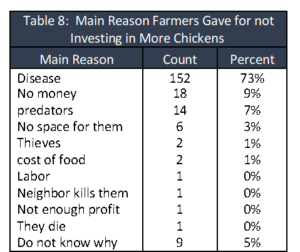

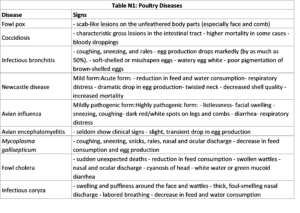

The chickens are typically free ranged, fed only enough to keep them from abandoning the homestead and becoming someone else’s chickens (Table 1). Typically few supplements or vitamins are provided. Sparse availability and resistance to paying the USD 0.10 for vaccinations against New Castle and coccidiosis—the most common diseases that afflict poultry– takes a heavy toll). Epidemics can and often do wipe out the entire poultry stock in a region. In the Chicken Survey, to be discussed in greater detail below, 73% of respondents said that they do not invest more in chickens because of disease (see Table 8). Other problems include predation by feral cats, mongoose, snakes, and dogs. Valentine (2010) reported farmers in the Department of the South annually lose 30% of their flocks to predators (n = 155). In a Telephone Egg Survey, discussed in more detail below, 55% of rural Haitian respondents reported that the primary reason for lost or spoiled eggs was predators (Table 2), the most problematic if which is the Mongoose, followed by feral cats and then dogs and rats (Table 3). Other explanations for why eggs are lost include stress on chickens from weather, dust, and eggs getting washed away or simply laid where the farmer cannot find them (Table 4). All of the preceding suggests that there is m uch room for improvement in traditional rural Haitian household level egg production. But there are significant constraints that must be understood within the context of the traditional Haitian livelihood strategies and the premises and objectives underlying those strategies.[ii]

uch room for improvement in traditional rural Haitian household level egg production. But there are significant constraints that must be understood within the context of the traditional Haitian livelihood strategies and the premises and objectives underlying those strategies.[ii]

Farmer Priorities in Raising Chickens

The most important point to understand about rural livelihood strategies in Haiti and how they effect egg production is that the guiding principal is minimal investment and minimal risks (for a more elaborate explanation of this principal go HERE). And as seen and explained in detail HERE there is no profit to producing eggs in Haiti when imported Dominican can be purchased for less than the needed high protein feed, and as discussed below, other factor take precedence over the eggs.

From Surveys, we know that egg production is not a main objectives of rural Haitians who raise chickens. When asked for the most important reason they raise chickens, 80% cite d reasons related to the value of the birds themselves: 43% of respondents said to sell the adult birds and another 37% said to eat them. Only 13% cited anything to do with eggs, 8% saying to eat eggs and 5% to sell them (see Figure 1). When asked about the second most important reason for raising chickens, 59% of respondents referred to adult birds, 38% saying to eat them and 21% to sell them. Only 21% said anything to do with eggs (see Figure 1).

d reasons related to the value of the birds themselves: 43% of respondents said to sell the adult birds and another 37% said to eat them. Only 13% cited anything to do with eggs, 8% saying to eat eggs and 5% to sell them (see Figure 1). When asked about the second most important reason for raising chickens, 59% of respondents referred to adult birds, 38% saying to eat them and 21% to sell them. Only 21% said anything to do with eggs (see Figure 1).

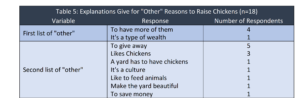

Also Insightful are the responses for those who chose “other” category (Table 5). Four of the five respondents who cited “other” explained that they raised chickens so they could have more of them. Of the 20% that cited “other” for the second most important reason why they raise chickens, typical responses were, “because I like chickens,” “they make the yard beautiful,” and “it’s a tradition.” And very importantly, although not often mentioned explicitly, when one tries to understand why rural Haitians “like” their chickens, why “it’s a tradition” and why they would prefer to raise live birds than eat the eggs, one should not forget that cockfighting is a type of national pastime for men in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic (see below).

Constraints to Producing Eggs

Feed

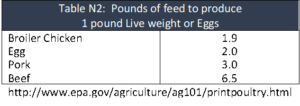

The first and most important limitation on egg production on rural homesteads is the same as that encountered at the industrial level, the cost of feed. Not any feed will do. A laying chicken requires very carefully balanced feed that includes the right salts, calcium and vitamins. One has to buy that feed, not easy to find in rural Haiti (see Constraints on Intensive Egg Production). If the farmer can get it from the poultry company Haiti Broilers then he or she can produce an egg for USD $0.11 cents. And that is basically the only hope the farmer has because even if the farmer can concoct the appropriate feed ratios—a feat for the most sophisticated farmer — retail corn prices in 2015 (100 Htg for 1 mamit = approximately 5.5 lbs) mean that at a conversion ratio of 4.6 pounds of feed one 1 dozen egg, the feed for an egg would cost exactly what it is worth on the retail market (7 to 8 Htg). And that is assuming that the farmer could get optimum industrial yield for the egg, something he or she could not hope to come close to. But that is not the worst of it. Corn in rural Haiti can vary seasonally by factors as great as 300%, so it at times it could cost 200% to 300% percent the given figure. If the farmers grows his or her own corn then, as seen earlier, it would make much more sense to forget about chickens and sell the corn. The only hope the farmer has, the only hope, is that when all is done he or she can sell the hens for slaughter and recuperate more than was lost. All of this makes feeding chickens highly inauspicious undertaking within the ‘low risk, low cost’ livelihood strategies that have enabled Haitian peasants to survive for two centuries. With the price of grain in mind, it is easy to understand why poultry production in rural Haiti is typically based on scavenging strategy, which leads to a whole series of additional constraints [iii] [iv] [v] [vi]

Constraints that Derive from the Scavenging Strategy

Because free ranging chickens will heartily scarf up any seeds they find means that they must be confined during planting and harvest seasons. If they are not confined and they invade a newly planted garden or help themselves to the neighbors drying corn, the neighbors have a right and often do kill them, often baiting them with rat poison. Because an effective chicken coup costs money–and as seen rural Haitians employ low risk and low investment strategies–the vast majority do not have coups. Rather they tether the chickens, which means tending them, moving them, watering them, all of which puts a limitation during planting and harvest seasons on the number that can be reasonably be looked after before they start dying from neglect. Indeed, the more chickens one has the more all the prior problems mentioned, the greater the costs, the risks, and the losses, all directly anathema to the major logical tenet underlying rural Haitian subsistence strategies: lost investment and low risk.

Disease and Supplements

To adequately care for a chick they should be given vaccines against Newcastle disease, and cocsidosis. They should be wormed and given vitamin supplements and preventative antibiotic, all of which is difficult to purchase for few birds and so much be bought in bulk at the cost of USD$20 to 30, more than half of what most rural farmers earn annually on chickens. Meds and nutrition will not stop predators, which as seen annually take 30% of the flock. Moreover, it is not as simple as vaccinating a chicken for life. To effectively deal with epidemics and new chicks, FAO recommends farmers vaccinate their entire flock of free-ranging birds monthly, making it a frequent cost and inconvenient chore not acceptable to most farmers. On top of all this, in most areas the vaccines simply are not available. In the best cases, supplies from the Ministry of Agricultural (MARNDR) are sporadic. In the other cases, such as Les Cayes, there is a functioning and well stocked store, but farmers must travel to get to it. [vii]

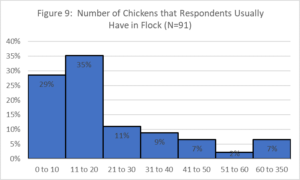

Chicken Carrying Capacity in the Context of Scavenging

Free-ranging introduces another limitation, that of ecological carrying capacity. Without supplemental feeding—as seen, too costly to make economic sense–carrying capacity is limited to the number worms, insects and small vertebrates available per unit land. Too many chicken’s means that supply of roaches, caterpillars and lizards gets exhausted and the chickens start to roam, increasing the likelihood of conflicts with the neighbors chickens, the neighbors, and a greater likelihood that chickens will be killed, poisoned or stolen. While we could find no reference to chicken carrying capacity under pure scavenging strategy, it is certainly far less than the maximum number of 120 chickens per hectare, that developed world farmers estimate with feeding, and may well hover around the 10 to 20 chickens that farmers in the Egg Survey cited as being the median sized flock.[viii]

The Pecking Order

Chickens have their own rigid and strictly enforced pecking order. They are territorial and do not readily accept strange birds. Even if Haitian farmers could purchase chicks –and the vast majority cannot—or if farmers could incubate them—and they cannot do that either (see below)—chicks and even adolescent birds cannot be simply turned out with the flock. Older birds will peck hatchlings to death. They have to be carefully protected and slowly integrated into the flock. The best way to accomplish that is under the protection of a broody mother hen, making an emphasis on brooding vs laying a logical strategy for peasant farmers. [ix]

Brooding vs. Laying

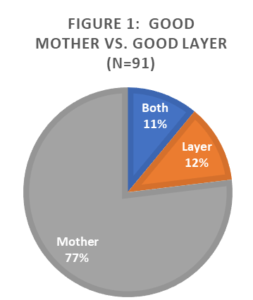

The most adaptive hen in the scavenging strategy described above is not the good egg layer but the good mother. What in chicken farming parlance is ‘broodiness,” the tendency to nest, to protect, young. Broodiness is precisely what rural Haitian prize in a hen (see Figure 6). Laying and broodiness are incompatible. The very definition broodiness means no more eggs: in other words, good mother = fewer eggs, explaining why a layer can yield 200 eggs per year while the typical rural Haitian chickens only lays 14 eggs per year.[x]

Cockfighting

A final but important aspect of raising chickens in rural Haiti is cockfighting, a national past time revered most among precisely the rural population in question and around which an entire economy circulates. Similar to markets, regions have their own circuits of gage (fighting rings). Specific rings have cock fights on a specific day of day of the week. Each year particular regions have their championships, known as dezafi. During this period the rings charge an entry fee. Betting on a single fight sometimes reaches as high USD $500 and even $1,000.

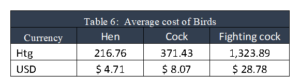

The importance of cockfighting places a premium on rearing cocks. Cocks sell for almost twice the price of hens (217 vs 371 Htg; see Table 6). Smaller birds are better for fighting—introducing a counter intuitive aversion to raising larger birds. Being proven in scraps with other cocks over a diet of coach roaches and lizards helps as well. Cockfighting aficionados keep their eyes open for young fighters demonstrating their prowess in bouts with other males in the yard. A young yard fighter that shows promise will be purchased for a much higher fee than other cocks. In the Egg Survey, 45 of 91 had sold a bird for fighting; the average highest cost was 1,324 Htg, about half the annual income from a flock in the IFAD funded “Smallholder Poultry Development Project” discussed below. The bird is then “prepared.” The trainer feeds his potential champion him a special diet, tethers him out of harm’s way, every morning gives him a bath, puts a hood on him and carries him affectionately under his arm when traveling or visiting cockfights. If the cock excels in the ring the trainer can earn 100s of dollars. A good cock can sell for 100 to 200 dollars, two to four times the annual value of the IFAD funded flocks.

Just How Many Chickens Do Farmers Raise

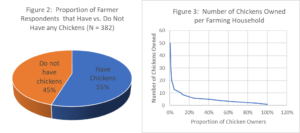

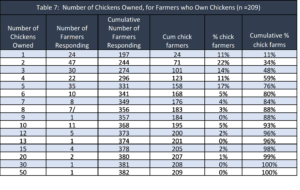

In the random sample of 382 households, what we are calling the Chicken Survey, 45% of rural households had no chickens at all. Moreover, while the average number of chickens per farming household was 4.8 chickens–similar to the national statistics and surveys cited above—the Chicken Survey yielded a median of 2 chickens per farming households (22% or 47 of the 209 farmers interviewed reported owning exactly 2 chickens). More than half all the chickens in the sample (544 of 1,015) were owned by only 25% of the farming households (51 of 209 respondents); 12% of the farmers (25 of 209) owned 36% of the chickens (363 of 1,015 chickens); a single farmer owned 5% of the chickens (see Figure 2 and 3 and Table 7).

It is not clear if the figures differ because of reporting error or if more than 50% of rural Haitian households are indeed without chickens. But as mentioned earlier, we know that household chicken flocks get periodically wiped out, particularly by disease (see Table 8).

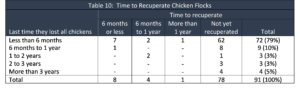

From the 91 household telephone survey it can be seen that 79% reported having lost their entire flock within the past six months (see Table 9). Because farmers do not have ready access to hatchlings, repopulation of the flock generally takes at least 6 months to 1 year (ibid). Moreover when we asked how many chickens respondents usually have, instead of the median of 5 birds seen in the Chicken Survey, we get a median of 11 to 20 birds. All the preceding suggests that the national data does not account for the periodic impact of disease. Nevertheless, the basic tenets of production built on low cost and los risk remain the same and help us understand the complexities of promoting egg production in rural Haiti.

Bureaucratic and Infrastructural Constraints

In addition to all the constraints mentioned above, when the Haitian farmer or the cooperative to which the farmer belongs has tried to become a small scale industrial egg producer he or she encounters the same obstacles that encumber the modern entrepreneur. Cost and availability of feed is be the biggest constraint. Technology is another. Without dependable electricity the farmer must improvise. In the place of electric heat lamps, he or she burns charcoal in barrels to warm the chicks. None of it is encouraging. Without an NGO underwriter, most farmers will not invest in vaccinations and feed supplements. Even the task of obtaining vaccinations is often not a matter of simply buying them, but finding them. Corruption, appalling inefficiencies, and apathy in both the civil sector as well as the NGO agricultural outreach programs means they are often not available. On top of these constraints, to have a profitable egg operation, the rule of thumb in Les Cayes area– according to agronomists and entrepreneurs who have tried to succeed at laying operations– is that there must be at least 200 hens, an investment of USD $4,200 to 4,400, far beyond the resources of most households. Moreover, for those who would invest, a far more lucrative and less risky endeavor is producing poultry for the meat. In approaching a conclusion and formulating recommendations, a series of additional challenges inherent in poultry production and aggravated by economic and infrastructural conditions in Haiti should be recognized.

- Chicken eggs must be incubated or sat on for 21 days, temperature must be maintained at 102.50 humidity must be 45 – 50% for the first 18 days and then raised to 65% for the last three days before hatching, objectives that mother hen is magnificently adept at accomplishing but not so easy for humans unassisted by sophisticated modern technologies. Eggs must also be turned three times per day. Without an incubator—or a mother hen–it is essentially impossible to hatch eggs. To use a hen is complex in itself because, as seen earlier one, chicks unprotected by a broody mother hen must be separated from the flock until they are able to defend themselves. What all this means is that farmers do not have a ready supply of chicks. As seen, 70% of Haitian hatchery capacity comes from the relatively new Enterprise, Haiti Broilers, an offshoot of Jamaica Broilers. Chicks purchased from Haiti broilers must be shipped in bulk to distributors, of which there essentially are none outside of Port-au-Prince, thereby eliminating the possibility of a rural farmer purchasing them. [xi]

- To produce a prime egg laying hen, the bird must be optimally cared for early in life. To achieve this they must receive vitamins and supplements. Lighting has to be manipulated. Their beaks must be trimmed during their first three weeks of life in the pullet to minimize cannibalism. What this means is that the surest source of prime laying hens is, again, Haiti Broilers, one of the other two outlets in Haiti (mentioned earlier on), or importing. The cost per layer from Haiti broilers is a moderate $11.00 to 12.00 per hen—essentially the same price as a creole hen on the local market. But this translates to $4,200 to $4,400 investment for the magical profitable minimum of 200 layers. [xii]

- To take maximum advantage of laying hens, the producer should exploit the molting reflex. Molting occurs naturally in the wild. Responding to seasonal daylight hours the bird stops laying, sheds her feathers and regenerates new feathers. She soon begins laying again at a reinvigorated rate. Chickens can be molted once or twice in the course of a lifecycle. But to induce molting means, again, controlling light exposure.

- Additional technological factors that must be controlled are temperature, humidity and ventilation, all of which affect laying output.

- Waste disposal is an issue, especially regarding stench associated with laying operations, which stink to the point of being a nuisance, far more so than broiler operations—which raise small chicks and then slaughter them before they become adults, i.e. the waste output is far less.

- Once again, feed is the greatest constraint. Imported and expensive in Haiti, high protein feed is only currently available from a handful of distributers. the most important and least expensive is Les Moulins D’Haïti, which up until 2010 was getting from the US Government an annual average of USD $5 million worth of US wheat at 70% of cost. Haiti Broilers has higher prices, and gets its raw material from the US, and a third—and untenable option–is the Purina licensed facility Ti Moulin which gets feed from the Dominican Republic, much of which originates in the USA. All three of these facilities are within several miles of one another, on the North side of Port-au-Prince. Only Haiti Broilers has best distribution network with more than 57 distributors throughout the country but the increased cost of getting food to producers means that the cost per egg for feed alone is 11 US cents (Chatelain 2012).

- The final issue with egg production is that Haitian Government itself, which has done little to ease the burden of starting a egg production business for those entrepreneurs who are interested in doing so. In contrast, on the other side of the border, Dominican Government subsidies to producers, monopoly control of their own market, reliable agricultural extension services, and far better roads and infrastructure give the Dominican producers an insurmountable advantage. They are able to manage their market in ways unthinkable in Haiti. For example during 2011 the average price of producing an egg in the Dominican Republic was $0.09; but the farm gate price was US 7 cents. In July 2013 the costs were unchanged but the farm gate price was almost double at USD 0.12. A porous border assures the Dominican produce will keep coming, while political instability and corruption assures the largest businessmen will pay little to no taxes. As seen earlier on in this report, staples such as cooking oil–and even eggs–come into the country far below the actual tax rates.

NOTES

[i] Laboratoire des Relations Haïtiano-Dominicaines (LAREHDO) financed by EU http://www.forumhaiti.com/t294-haiticapacites-dans-la-production-des-oeufs

[ii] Here are the 8 major diseases likely to affect free ranging chickens (IFAS 2014)

[iii] FAO FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS 2003 Egg marketing A guide for the production and sale of eggs ISBN 92-5-104932

[iv] For the Corn to Calorie calculation I used Google Calculator based on United States Department of Agriculture

Agricultural Research Service National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 27. https://www.google.ht/webhp?sourceid=chrome-instant&ion=1&espv=2&ie=UTF-8#q=calories%20in%201%20cup%20of%20corn

[v] For the American Heart Association caloric intake recommendations see, http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/Dietary-Recommendations-for-Healthy-Children_UCM_303886_Article.jsp

[vi] Chickens are extremely efficient at converting feed to protein in the form of meat. It takes 2 pounds of grain to obtain 1 pound of live chicken.

[vii] Testament to fact is that many farmers want to treat their birds and are disposed to purchase the medicine and take the time to do so is that widespread use of Ampicillin, a locally available antibiotic for humans, that farmers mix with lime juice and coffee to treat ‘colds.’

[viii] See BackYard Chickens, how many chickens per acre?

http://www.backyardchickens.com/t/288496/how-many-chickens-per-acre

[ix] For example, see A Guide To Understanding The Chicken Pecking Order at BackYard Chickens

http://www.backyardchickens.com/a/a-guide-to-understanding-the-chicken-pecking-order

[x] “Being in a state of readiness to brood eggs that is characterized by cessation of laying and by marked changes in behavior and physiology” “Merriam-Webster definition”. Retrieved18 September 2012.

It’s useful to also note that it is much easier to induce broodiness than to induce egg laying qualities which also are dependent on selective breeding regimes. But once you have lost the broodiness, it takes time and breeding to get it back This from, http://www.backyardchickens.com/a/encouraging-or-discouraging-broodiness-in-your-hens

“For those who are strictly interested in getting the most eggs out of their flock as possible, broodiness would not be a desirable trait. For the 2-3 months that the hen is broody, she won’t lay any eggs. The good news is that most of the modern high production breeds have been selectively bred and rarely “go broody”, including the Leghorns, Sex Links, Production Reds, & Rhode Island Reds. Many of the other breeds rarely go broody, but there are always a few exceptions.”

And from http://www.hobbyfarms.com/livestock-and-pets/broodiness-in-chickens.aspx

“For example, breeds that have been developed for high egg production have also been bred to not be broody; they are least likely to set on a clutch of eggs and brood it naturally.”

This from, http://www.backyardchickens.com/a/encouraging-or-discouraging-broodiness-in-your-hens

“For those who are looking to be more self-sufficient in terms of raising replacements in their flock, broody hens are a very useful asset.”

One of the other reasons it’s recommended to separate the broody hen is that other flock members might view the chicks as “intruders”. Especially when they rest of the eggs are hatching, and the mother hen can’t be there to protect a wandering chick. You also want to make sure they can’t squeeze through any fencing separating the broody hen and the rest of the flock. The general consensus is to wait until the chicks are at least 1 or 2 weeks old, before letting the broody hen and the chicks intermingle during the day with the rest of the flock. Some people, including myself, have been successful in allowing the broody hen and chicks forage during the day with the rest of the flock from only a day or two old, but I would be cautious, as it may not work for everyone.

“There are many benefits to having a broody hen raise the chicks, rather than by a human. Even if the eggs are hatched via incubator or the chicks are from a hatchery, I personally think that the broody hen does a great job raising them. Not only do you save money by not having to use a heat lamp, but you can also save a little food cost. The mother hen teaches the chicks from a very early age how to forage their own food, often much sooner than if we humans were raising the chicks. She has a food call very similar to a rooster, which she uses to call the chicks to her when she’s found a tasty morsel. Plus, a broody hen will gradually integrate the young chickens into the rest of the flock, causing less pecking and commotion. Some broody hens will even teach the chicks to roost with the other birds inside the coop. I personally love watching the interaction between the mother hen and chicks, and how they learn to copy her every movement. For each hen, it will vary how long she stays with the chicks, but most will stay with them for around 6-8 weeks. She will gradually let the chicks wander around on their own, and leave them for a few minutes at a time. Even after the chicks have “graduated” into independence, the broody hen may once in awhile “check” on them.”

“They are great on farms that want to be self-sustainable or in case of a power outage when you can’t use an electrical incubator. The broody hen will also protect and teach the young chicks. They do however stop laying eggs while being broody and this is a problem for some.”

[xi] “Lighting plays a very important role in bird growth, development, and maturity. Most commercial poultry specie are photosensitive animals. For example, a constant or decreasing amount of daily light (as occurs during the fall and winter months) will delay sexual maturity in growing birds. An increasing amount of light (as occurs in the spring) will stimulate sexual maturity. Since lighting plays such an important role in the development of sexual maturity, adolescent birds are generally reared in black-out houses. This allows the producer to have complete control over the lighting cycle of the birds by providing artificial light.” http://www.epa.gov/agriculture/ag101/printpoultry.html

[xii] The prime egg producing hen begins laying eggs at ~18 weeks of age and reaches maximum laying capacity—approximately .5 to 1 egg per day 4 to 6 weeks after she begins laying.