Peanuts are endemic to Haiti. Pre-Columbian Taino Indians planted them. Haitians have always planted and eaten peanut products as, or more frequently, than any other food that is not part of the main mid-day meal. Haitians prefer locally produced varieties over imported peanuts. In this paper we examine the peanut value chain, taste preferences, and consumption patterns. The research comes from a review of the literature, focus groups, key informant interviews, surveys, store inventories, and extensive cultural consensus analysis studies, all conducted on behalf of the American Peanut Council in 2015, and all of which can be reviewed in detail here.

The Peanut Ethnographic Value Chain in Haiti

The Peanut Value Chain

Peanut products are currently part of an Haitian artisanal industry, and an important one. Roasted peanuts, locally grown, locally processed, locally transported, and sold by low-income female traders. Peanut sugar clusters, chanm chanm, and peanut butter are all peanut treats made by homemade by Haitian women and sold on front porches, roadsides, markets, and boutques.

Peanut Production

TechnoServe’s 2012 landmark peanut value chain report estimates that 35,000 Haitian households are involved in production, producing a total of 14,000 metric tons per year. Another 15,000 households depend to some extent on the peanut value chain through the processing and marketing of roasted peanuts, peanut butter and other peanut products discussed below. The production occurs almost entirely on small farm plots, with each farmer cultivating an average .65 hectare in peanuts.

We believe the TechnoServe estimates to be conservative. TechnoServe cites three primary peanut producing regions in Haiti. Using Port-au-Prince market sellers, they estimate the relative importance of the North at 7 percent of production, the Northeast at 8 percent, and the Central Plateau at 71 percent. However, significant quantities are grown in the South (based on common knowledge as well as Jolly and Prophete, 1999). And peanuts are produced at some level throughout the country. Even in the dry Department of the North West peanuts are the major cash crop grown in many mountain areas where they are intercropped with tobacco, castor beans, sorghum, melons, squash, okra, pigeon peas, sweet potatoes, and sesame. They are also grown at lower altitudes of the North West, in loamy patches of desert where, farmers report, just two rains can be sufficient to obtain a profitable yield.

The Market

Peanuts are definitively a market crop. TechnoServe (ibid) estimates that 5 percent or less of Haiti’s peanuts are consumed by the household that produces them. TechnoServe estimated that only another 5 percent of peanuts go to the formal sector: 3-4 percent to industrial peanut butter and peanut processors, 1-2 percent to RUTFs manufactured by the only two social enterprises in Haiti that engage in the sector, PIH and MFK. Fully 95 percent of peanuts were going to the informal sector: 46.5 percent sold immediately after harvest, and 44.9 percent stored for subsequent sale over a period extending to six months, during which time the revenue generated eventually reaches three times the price at the time of harvest. (see also Jolly and Prophete, 1999).[i]

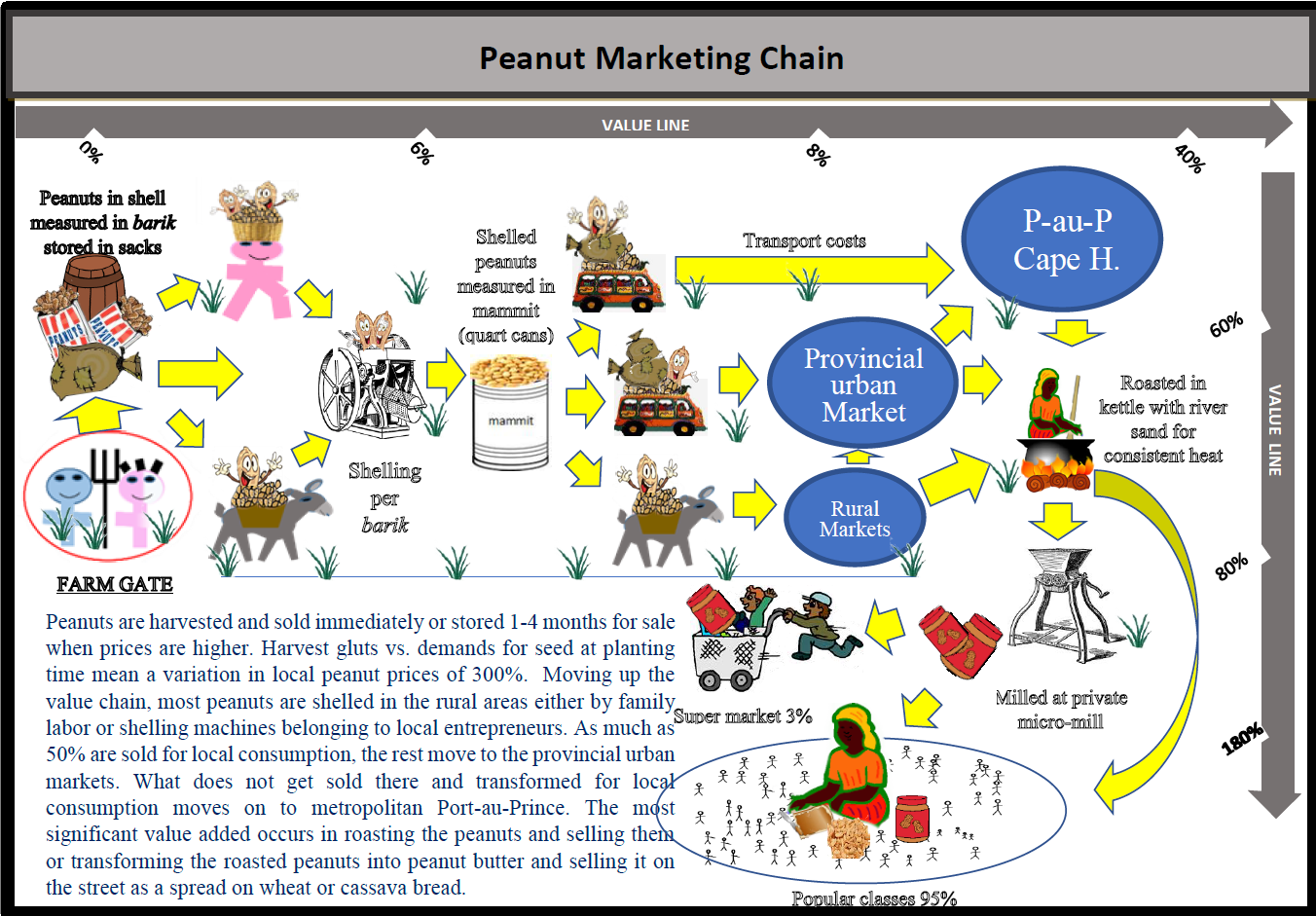

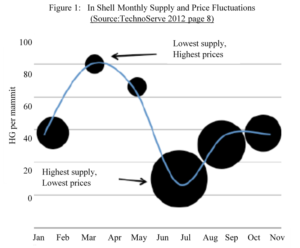

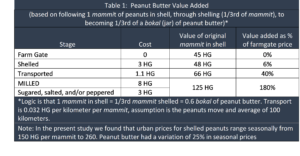

At harvest peanuts are measured by the barik (barrel), but stored in sacks. After shelling they are measured by the mammit (4 quarts). There are 40 mammit of unshelled peanuts in 1 barrel, and generally speaking, 3 mammit of unshelled peanuts will yield 1 mammit of shelled peanuts. Shelling is almost always done in rural areas. Family labor and the availability of shelling machines–with a cost of 1 HG per mammit–mean that value added is minimal. The peanuts are then shipped up the market chain from rural market to provincial urban markets and Port-au-Prince. TechnoServe estimates the cost of transport at 0.032 HG/mmt/km (Haitian HG per mammit per kilometer). Markup on prices move at a rate of about an 8 percent increase from provincial to secondary markets

At each stage of the market some of peanuts are purchased, processed into roasted peanuts and sold as peanuts in small 5-10 HG plastic bags or converted to peanut butter and sold with a value of ~5 HG as a spread on bread or cassava. The profit between purchasing raw shelled peanuts and converting them to peanut butter is as high as 80 percent (see Table 1)

Problems and Inefficiencies in the Production and Market Chain

There are apparent problems and inefficiencies in the peanut production process and marketing chain in Haiti. TechnoServe sums them up as the lack of a relationship of prices paid to quality of peanuts, or moisture content, and zero awareness of aflatoxin (something Western researcher on the topic determine to be a dangerous carcinogen).[1] Another issue is that, as with most products seen earlier, the final peanut butter products sold even in elite super markets have no labels and no expiration dates. TechnoServe analysts also conclude that Haitian peanuts are costly—with shelled peanuts prices averaging 1600 and 2500 USD/MT in Haiti vs. 1250 to 1350 USD on the international market.

The reality of retail market price suggests that there is, in fact, something highly cost efficient about the local value chain. Despite claims of seasonal shortages, TechnoServe observed a constant year-round flow of peanuts into Port-au-Prince’s primary produce market (Bosal). The costs of peanuts and peanut butter on the street also are remarkably consistent, changing seasonally by a factor of only 25 percent, compared to the 300 percent variation for peanut seed in rural areas. This is true for two reasons, 1) the shelf life of peanuts and peanut products–raw peanuts can be stored for 3 to 4 month and peanut butter stores for another 2 to 3 months, easily spanning the two seasons, and 2) seasonal mountain vs. plain harvests found throughout Haiti result in 3 to 4 harvest periods per year.

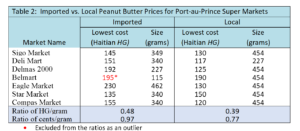

Local processed peanuts and peanut butter are not only preferred by consumers, they are 25 percent less expensive for consumers than the imported counterparts (see Table 2). Moreover, while taxes and transport on imported shelled peanuts bring the price for a MT to USD $1,900, the low point for shelled Haitian peanuts, at harvest, is $800 USD/MT. In effect the market chain, actors and interplay of profits in Haiti seem to work out to the benefit of the urban consumer.

None of this is to say that only local peanut butter is on the market. In visits to 19 urban supermarkets, we found that all stocked imported peanut butter brands. But that is as far as imported peanut butter gets. It is conspicuously absent from the popular market. One can infer that part of the reason for their absence is the lower cost–as seen, arguably the major determinant of food consumption in Haiti.

Official Imports have increased dramatically in the past two decades, from 16 metric tons of peanut butter in 1998 to 104 metric tons in 2008. However, if accurate, this represents less than 1 percent of domestic production. At 20 metric tons in 2012, MFK was the only known importer of whole peanuts (Illustrative of the problem with customs and records is that imported peanuts are nevertheless present in supermarkets). It is difficult to evaluate what this means because, as seen in Section 7 above, corruption and poor record keeping at the ports mean that customs data often says more about politics than actual flows of merchandise.

The participation of popular micro-entrepreneurs and the highly integrated informal market system—vs. a clumsy and poorly developed formal sector—are surely key factors that help explain the low cost of domestic peanut products. Family labor is involved in production, shelling, packaging, transport and processing. Peanuts are the most commonly transformed food in Haiti, so one finds mills even in urban neighborhoods, and one would be hard pressed to find an adult woman who has not, at some time in her life, processed and sold peanut butter. Moreover, the actual creation of the peanut butter is only the second step in the value chain. The entire chain can—as seen in Figure 2 above– touch as many as eight market actors: grower, 1st purchaser, sheller, transporter to 2nd market, 2nd purchaser and processer of peanuts, miller, purchaser of peanut butter in bulk, retailer vendor of peanut butter and bread or cassava.

Consumers Opinions, Preferences and Tastes

Health and Who Consumes Peanuts

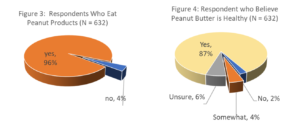

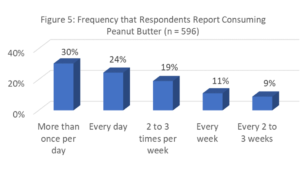

Although only 1 respondent in the 50-respondent ‘most nutritional foods’ survey mentioned peanuts, 87 percent of people in a 632 respondent Consumer Survey said peanuts and peanut butter are good for the health (Figure 4). Indeed, the importance of peanuts in the popular class diet cannot be overstated. Only 26 of the 632 respondents in the Consumer Survey (4 percent) said they do not eat peanuts (Figure 3); fully 96 percent said they eat peanuts or peanut butter, 54 percent of these eating them at least once per day, and 30 percent eating them more than once per day (Figure 5). [ii]

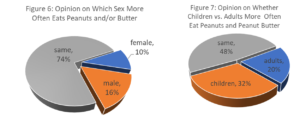

We know anecdotally and from focus groups that peanuts are widely thought of as having sexually invigorating properties for men, but only 16 percent vs. 10 percent of Consumer Survey respondents said that men consumed them more often than women and 74 percent said that men and women consumed them with equal frequency (Figure 6). Similarly, peanuts and peanut butter are thought almost as much a food for adults as for children: only 32 percent of respondents said that children more often than adults consume peanut butter and peanuts; 48 percent said adults and children consume them with equal frequency, while 20 percent thought that adults consume more than children (Figure 7).

Peanut Base Foods

Peanuts are excluded as an ingredient in the main mid-day meal. We found no reports of any main dish or soups having peanuts. The point is especially peculiar in that peanuts are a salient ingredient in some dishes in West Africa, the population from which Haitian slave ancestors originated. The most important such dish is West and Central African “peanut soup.”[iii]

Nevertheless, peanuts are eaten in such a way that they appear strategically important outside of the mid-day meal. In some areas, notably Gonaives, peanuts are eaten on slushed ice. They are sometimes an ingredient in fortified shakes and blends–such as akamil and akasan—and they are a key ingredient in the powdered peanut-corn blend called chanm chanm (all three foods introduced into the Haitian dietary regime through efforts of NGOs and all three rare violations of Haiti ‘food syntactical’ rule of exclusion seen in ##). Throughout Haiti popular class women make and sell peanut clusters. In some areas they make a type of peanut brittle. The sugar-peanut combination in all these formulations are a high energy snack and, until the invasion of packaged cookies over the past two to three decades, these artisanal peanut confections were one of the premier popular class treats (dous, pure sugar clusters and coconut sugar clusters being two others). However, the most common forms in which peanuts are consumed are, 1) roasted (sold in clear plastic bags for 5 and 10 HG – 12.5 to 25 cents) and 2) as peanut butter (sold as a spread on bread and cassava at a value of 5 HG).

Peanut Butter

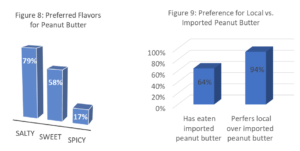

Peanut butter is prepared from roasted peanuts, sugar or salt and, in the case of the latter, varying degrees of hot pepper are added, a fact inadequately represented in the data. The most preferred flavor is salty (79 percent) but more than half of respondents also like sweet peanut butter (58 percent)–Figure 8. Congruent with respect to local produce, Haitians overwhelmingly prefer domestic over imported peanut butter (Figure 9).

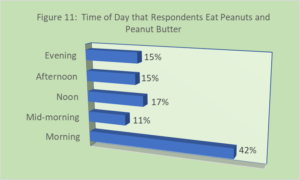

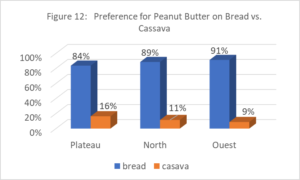

Respondents prefer peanut butter over peanuts 60 percent to 16 percent, with 24 percent reporting they like both equally (Figure 10). Both are overwhelmingly considered to be breakfast foods, consumed in the morning to mid-morning (Figure 11). Peanut butter is most frequently smeared as spread on wheat bread and to a lesser extent cassava bread (Figure 12).[iv] Vendors who sell peanuts, peanut butter, bread and bananas also sell eggs.

Expenditures on Peanut Butter

The average reported expenditure on a single peanut butter purchase is 153 HG (USD3.00), but we believe this is an error in the way the question was posed and reflected not consumption so much as the common practice among women of purchasing peanut butter for resale. We know anecdotally and from interview with vendors that the most common way that people purchase peanut butter is not in a container but as a spread on bread or cassava that the vendor values at 5 to 10 HG but that some vendors use simply as an inducement to selling the bread or cassava. Sixty-seven percent (67 percent) of buyers want to purchase more, and 88 percent would purchase more if it were less expensive.

Bibliography

Beghin, I, Fougere, W., King, K.W. (1970), L’Alimentation et la Nutrition en Haiti”, publication de L’I.E.D.E.S., Presses Universitaires de France, 108, Blvd. Saint-Germain, Paris.

Berggren et al. 1984; King et al. 1968; 1978; Berggren 1971, Beaudry-Darismé 1971; Beaudry-Darismé and Latham 1973; Berggren et al. 1985; Mduduzi N.N. 2013; Dornemann and Kelly 2013; Schwartz 2009

Berggren, Gretchen, Nirmala Murthy, and Stephen J Williams. 1974. Rural Haitian women: An analysis of fertility rates. Social Biology 21:368–78.

CFSVA (Comprehensive Food security and Vulnerability Analysis) – 2007/2008. Overseen by WFP (World Food Program) and CNSA (Coordination Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire)

CIAT 2015 AgroSalud Project (www.AgroSalud.org)

CNSA and WFP’s 2007 Analyse Compréhensive de la Sécurité Alimentaire et de la Vulnérabilité (CFSVA) Written by Timothy Schwartz

CNSA’s 2011 Enquête Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire (ENSA),

Demographic Health Surveys (DHS or EMMUS) from the year 1995 (N=4,944 households), year 2000 (N=9,595 households), year 2005 (N=9,998 households), and year 2012 (N=13,181 households)

DeWind, Josh and David H. Kinley, 1988 Aiding Migration: The Impact Of International Development Assistance On Haiti 3rd

EMMUS 2012 Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haïti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti

EMMUS-I. 1994/1995. Enquete Mortalite, Morbidite et Utilisation des Services (EMMUS-I). eds. Michel Cayemittes, Antonio Rival, Bernard Barrere, Gerald Lerebours, Michaele Amedee Gedeon. Haiti, Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-II. 2000. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Florence Placide, Bernard Barrère, Soumaila Mariko, Blaise Sévère. Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD: Macro International.

EMMUS-III. 2005/2006. Enquête mortalité, morbidité et utilisation des services, Haiti 2000 (EMMUS-II). Cayemittes, Michel, Haiti: Institut Haitien de L’Enfance Petionville and Calverton, MD : Macro International.

FAFO 2001 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume II

FAFO 2003 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume I

FAO Stat 2000

Farmer, Paul, 1988Bad Blood,Spoiled Milk: Bodily Fluids as Moral Barometers in Rural Haiti (1988)

Gardella, Alexis 2006 Gender Assessment for USAID Assessment Country Strategy

HarvestPlus 2013 Prioritizing Countries for Biofortification Interventions Using Country-Level Data HarvestPlus Working Paper | authors, Dorene Asare-Marfo Ekin Birol Carolina Gonzalez Mourad Moursi Salomon Perez Jana Schwarz and Manfred Zeller

Hinds, . M.J. M. Jolly, R.C. Nelson”, Y. Donis”, and E. Prophete”

IDB 1999 see Gardella, Alexis,

International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2015 HAITI SELECTED ISSUES Prepared By Lawrence Norton, Joseph Ntamatungiro, Daniela Cortez, Gabriel Di Bella (all WHD), Emine Hanedar (FAD), and Anta Ndoye (SPR) Approved By The Western Hemisphere Department

Institute Haitien de L’enfance et al (2000),

Jensen, Helen 1990 Food consumption patterns in Haiti Center for Agriculture and Rural Development. Iowa State University Staff Report 90-SR 50

King, K.W. Fougere, W., and Beghin, I. (1966) Un Melange de proteins vegetales (Ak-1000) pour les enfants haitiens.Ann Soc. Belge Med. Trop. Vol 46, 6, pp 751-754.

King, K.W., Fougere, William, Foucald, J., Dominique, G., and Beghin, I (1966) Responswe of [preschool children to high intakes of Haitian cereal-bean mixtures. Arcivos Latinoamericanos de Nutricion 16:1. pp 53-64.

Schwartz, Timothy. 2009 Fewer Men, More Babies: Sex, family and fertility in Haiti. Lexington Press. USA

Stam, Talitha 2012, From Gardens to Markets Rural women on the move to urban markets, Route Seguin Haiti A Madam Sara Perspective Commissioned by CORDAID for the IS ACADEMY Human Security in Fragile States

Technoserve 2012 HAITIAN PEANUT SECTOR ASSESSMENT Strategic Industry and Value Chain Analysis (Haiti)

The Guardian 2015. The west’s peanut butter bias chokes Haiti’s attempts to feed itself Guardian Global development http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jul/10/haiti-peanut-butter-food-aid-malnutrition Accessed, 1/03/15

USDA 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Chapter 6. (Accessed 18/12/09) (http://www.health.gov/DIETARYGUIDELINES/dga2005/document/html/chapter6.htm)

WHO (2009) World Health Organization, Global and regional food consumption patterns and trends http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/3_foodconsumption/en/index3.html

NOTES

[1] Anecdotally, we can attest that popular class know nothing of the threat of aflatoxin and even educated Haitian elites typically refuse to accept it as a credible hazard

[i] Consumer Acceptability and Physicochemical Properties of Haitian Peanut Butter-Type Products (Mambas) Compared with u.s. Peanut Butter M.J. Hinds!”, C.M. Jolly, R.C. Nelson”, Y. Donis”, and E. Prophete”

[ii] Peanuts not being mentioned in the ‘most nutritious foods’ list may have something to do with them not being consumed in association with the main meal and a consequence of them being so commonly consumed that respondents simple took them from granted:

[iii] At the time of the Haitian Revolution over 50% of the slaves had been born in Africa.

[iv] Because cassava bread is a major product in the North of Haiti and a common street food—vs. Port-au-Prince and Gonaives where it is seldom even seen on the street–we expected that more people would consume it with peanut butter than in other parts of the country. We did not find this to be the case.