Targeting strategies are as old as humanitarian aid, but the formal study of targeting is recent, arguably only beginning in the past decade. To date, much of what is written is unclear.

This paper is intended to present a synthesized model of humanitarian aid targeting that will clarify the many ambiguities and differences in other models.

The research was originally conducted on behalf of the Haitian para-statal institution CNSA (Coordination Nationale de la Sécurité Alimentaire), with financial support from WFP, and FAO.

[for those more interested in implementation see, A Guide for Beneficiary Targeting, Freq-Listing as well as Notab Leadership and Key Informant Network Strategy (NOLKINS)]

Definition of Targeting

Sharp, K. (1997), defines targeting as,

…the process of identifying the intended beneficiaries of a programme and then ensuring that, as far as possible, the benefits actually reach those people and not others.

Maxwell et al (2009:3) define Targeting as,

… the act of ensuring that aid reaches people who need it at the right time and place, in the right form and quantity—and at the same time does not go to people who don’t need it.

The World Bank defines Targeting as,

Targeting seeks to deliver benefits to a selected group of participants, in particular poor and vulnerable people. Targeting mechanisms attempt to link a project’s specific purposes with its intended group of beneficiaries. There are many ways to target programs, and most CDD projects use more than one targeting mechanism. They include geographic mapping, household surveys, censuses, qualitative surveys, and “self-targeting.”[i]

WFP (2006b:1) defines targeting as,

At its broadest, targeting encompasses everything from initial assessment of the context, extent and magnitude of need through strategic planning and modality selection to eligibility selection and screening, which in turn leads to re-assessment of need through monitoring and evaluation.

Basic tenets and goals of Targeting include,

- to reach those most in need of food (WFP 2006b)[ii]

- to maximize the use and impact of limited resources (WFP 2006b)

- to not over-supply food aid, which may result in negative impacts on communities, for example dependency and displacement of traditional social reciprocity networks, and on markets, for example lower prices and disincentives to production (WFP 2006b; Maxwell et. al 2009:4)[iii] [iv]

In understanding targeting, the concept should not be limited to the most vulnerable. There are ways to aid the most vulnerable other than direct relief, specifically helping increase agricultural yields or other productive economic activities. For example, National plans for food security often include aid to farmers with the goal of increasing production through improved seeds, application of pesticides and fertilizers and use of advanced cultivation strategies. With the importance of maintaining or increasing production in mind, WFP has also posited that underlying objectives of targeting should,

- in addition to those whose lives are at risk, target those at risk of losing their livelihoods (WFP 2006a:7)

- empower populations to feed and care for themselves (WFP Emergency ibid)

And very importantly, reviews of targeting suggest that without community acceptance aid may generate conflict and resentment, doing more to disrupt a community than contribute to recovery and reinforcement of livelihood strategies (see Himmelstine 2011) Thus, we can add another maxim that should apply to most Targeting, particularly targeting associated with non-emergency aid,

- Buy-in: targeting should achieve community acceptance and support

Examples of times that buy-in would not be applicable are cases of conflict and strife between different ethnic groups, class, or political factions. In these cases buy-in should be applied to the respective target sub-communities, but without doing harm to the other communities, ethinic groups, or classes.

Categorizing and Targeting Models

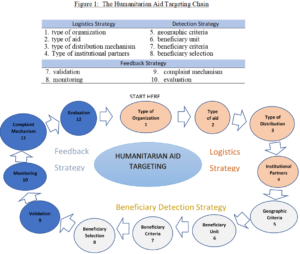

Some reviews and guides present targeting as a series of steps (e.g. WFP 2006a). Most explore targeting as a strategy to intelligently negotiate what is often a bewildering array of conflicts, politics and cultural idiosyncrasies (Maxwell et al 2009; WFP 2006b; Himmelstine 2011). Lamaute-Brisson (2009) emphasizes understanding Targeting from an institutional perspective. Several useful attempts to targeting categorize the different processes involved in targeting; most notable is Lavelle et. al. (2010). While it is useful to conceptualize Targeting as a delimited domain or set of steps, and we draw heavily on the works cited above, targeting can and arguably should be understood as more than an activity or phase of the aid process: Targeting should be understood as a dimension of aid that, whether by design or simply consequence, is embedded in every operational decision an organization makes:

- beginning with the moment an organization defines itself as dedicated to a particular type of assistance (disaster relief vs. development, medical care, agricultural, financial or educational sectors)

- to the selection of the region, country, zone or ethnic group the organization will work in (Asia or the Americas, Guatemala or Haiti, Urban or Rural, ecolo-economic zone)

- to deciding on the specific type of aid it will give (for example, medical care that is preventative vs. curative, seeds vs. food, money vs. vouchers)

- to deciding how the aid will be distributed or transferred (subsidies, cantine, voucher, cash transfer)

- to selecting the beneficiary units that will receive the aid (school, health clinic, association, household, individual)

- to determining the criteria that will define a beneficiary (low income, landless, HIV positive, disabled, pregnant, farmer)

- to deciding how the individuals who fit the criteria will be detected (committees, networks of extension agents, surveyors)

- to deciding who will do the selecting (members of the community, Community Based Organization)

- to the actual selection of the recipients

At each stage the field of who will receive aid is narrowed. After selection is made, most organizations should,

- validate whether or not the correct beneficiaries were chosen (narrowing or broadening the field of who is about to receive aid)

- monitor who is really receiving aid (narrowing or broadening the field of who is currently receiving aid)

- seek feedback from beneficiaries or members of the community through one or several complaint mechanisms (broadening the field of who receives aid)

- evaluate the effectiveness of the targeting, meaning did it accurately identify who needed aid (narrowing or broadening the field of who will subsequently receive aid)

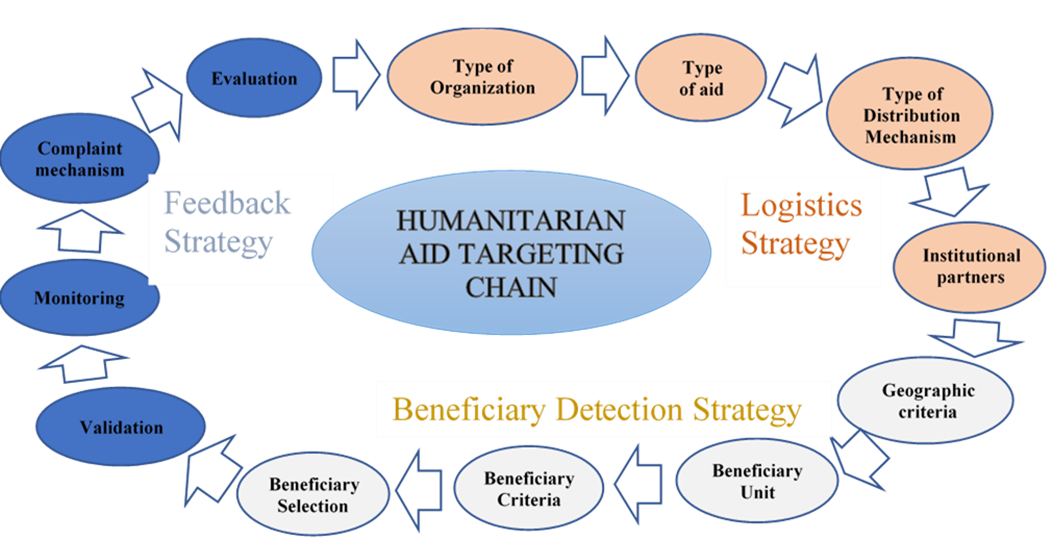

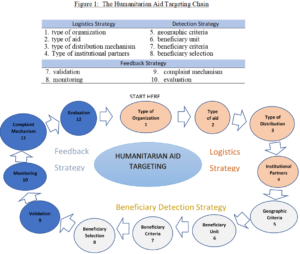

In this way the aid process can be conceptualized as a decision making chain in which the choice of beneficiary is increasingly refined (see Figure 1).[v]

In effect, Targeting should be understood as not just a process, but a dimension of aid, present at every stage of the aid chain. It can be separated into distinct groupings (as illustrated in Figure 1), specifically choice of Logistic Strategy, choice of Beneficiary Detection Strategy, and choice of Feedback Strategy. The core processes of Targeting, and what all the studies cited above share in their focus is the middle category, what we define here as Beneficiary Detection Strategy. This includes Geographic Criteria, Beneficiary Unit, Beneficiary Criteria and Beneficiary Selection. However, it is important to keep in mind that, although not dealt with extensively here, logistics and feedback have more to do with who ultimately gets the aid than the choice of intended beneficiaries.

Beneficiary Detection Strategy

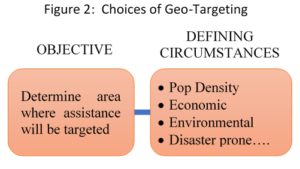

Geographic Area/criteria Overview

The definition of geographic criteria could begin with continental zone, cultural areas, and political border, although, these categories are here omitted and geographical criteria is limited to economic, ecological, and demographic dimensions; for example, farmers (economic), in areas that are littoral–dry (ecological), and rural (demographic). The definition of a geographical criteria can be conditioned by disaster prone dimension of vulnerability, as in people living in flood prone areas, or hurricane strike zones, or people in areas of military or ethnic conflict. Geographical criteria can also be extended to include infrastructure and state control; for example, areas with low levels of infrastructure or state services. While remoteness and weak infrastructure are often selection criteria, in practice geo-infrastructural criteria often work against the poor. Regional food distributions can be contingent on road access, meaning that food assistance is directed away from underdeveloped regions to those with infrastructure and, by corollary, toward those that already receive greater services from the State or other service providers. It can also and often is contingent on security concerns, such that high crime urban areas, military zones, or access to hard hit disaster areas—precisely those that most need aid–are restricted or even made off-limits to aid workers. As with all aspects of the selection process, although the ultimate objective may be alleviation of poverty, hunger, or associated afflictions, the aid may be intended for those who are not vulnerable. An organization may target farmers in high agricultural production regions and relatively wealthy farmers with the goal of increasing locally available foods and employment. In summary we can divide Geographical Criteria into the following six categories:

- Population density (Urban, peri-urban, and rural)

- Economic zone (low income areas or farming, pastoral, hunting, mining, logging)

- Ecological zone (littoral dry, humid plateau, humid mountain, dry mountain)

- Ethnic or Socio-cultural/linguistic groupings

- Infrastructural and service conditions (availability of services such as schools or infrastructure such as water, roads and electricity)

- Security situation/restrictions (conflict or high crime areas, zones of guerilla activity)

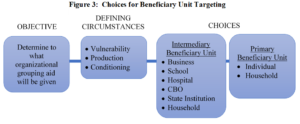

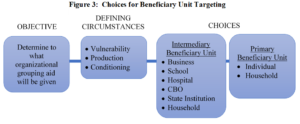

Beneficiary Unit Overview

The ultimate target of most humanitarian aid is impoverished or needy individuals or households. These are primary Beneficiary Units and  are examined in depth later in this report. However, what should also be included in this category are those entities or organizations used to pass aid on to recipients, what can be defined as “Intermediary Beneficiary Units.” These may be an enterprise, such as a bank, small business, school, or cooperative serving the poor; it may be a CBO, such as a church, orphanage, farming cooperative, or women’s association. Even NGOs, whether international or local, may themselves be conceptualized as Intermediary Beneficiary Units. The selection of a beneficiary unit at a level above the individual or household typically makes aid disbursement administratively easier for the organization because they can use the intermediaries system of beneficiary identification and distribution. But it often makes it more difficult to reach intended recipients because of the necessity of conforming to administrative and infrastructural exigencies. For example, financial assistance to CBOs (Community Based Organizations) is often contingent on their having a bank account, eliminating organizations with the most impoverished members or making them vulnerable to unscrupulous individuals who offer to facilitate access to banking services but intend to embezzle the aid; voucher programs may be conditional on the individual’s physical presence, eliminating the disabled or those individuals, often the poorest, who live in remote areas; assistance to school feeding programs may be conditional on secure dry storage facilities and proper accounting procedures, eliminating the most impoverished schools; assistance to children can be conditional on their being in school, eliminating the poorest children.

are examined in depth later in this report. However, what should also be included in this category are those entities or organizations used to pass aid on to recipients, what can be defined as “Intermediary Beneficiary Units.” These may be an enterprise, such as a bank, small business, school, or cooperative serving the poor; it may be a CBO, such as a church, orphanage, farming cooperative, or women’s association. Even NGOs, whether international or local, may themselves be conceptualized as Intermediary Beneficiary Units. The selection of a beneficiary unit at a level above the individual or household typically makes aid disbursement administratively easier for the organization because they can use the intermediaries system of beneficiary identification and distribution. But it often makes it more difficult to reach intended recipients because of the necessity of conforming to administrative and infrastructural exigencies. For example, financial assistance to CBOs (Community Based Organizations) is often contingent on their having a bank account, eliminating organizations with the most impoverished members or making them vulnerable to unscrupulous individuals who offer to facilitate access to banking services but intend to embezzle the aid; voucher programs may be conditional on the individual’s physical presence, eliminating the disabled or those individuals, often the poorest, who live in remote areas; assistance to school feeding programs may be conditional on secure dry storage facilities and proper accounting procedures, eliminating the most impoverished schools; assistance to children can be conditional on their being in school, eliminating the poorest children.

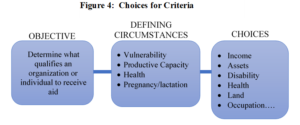

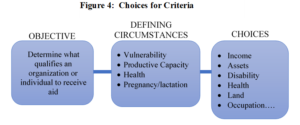

Beneficiary Criteria Overview

Beneficiary Criteria refers specifically to who is meant to benefit from an aid. With regard to aid to the vulnerable, we can identify four types of beneficiaries (Lavalee et al 2010):

- those who have little hope of overcoming their status because of disability or age,

- those who are discriminated against because of some culturally defined status such as gender, ethnicity, age, religion, caste or occupation

- the transient poor who have fallen on hard times because of a crisis in their own lives or the lives of a member of their family, such as in the case of illness or debt

- disaster victims who have been hit by a widespread shock such as hurricane, earthquake, war, or economic recession

The status of category 4, above, that of disaster victims, tends to be aggravated by inclusion in the former categories. Specifically, in the event of a regional calamity those who tend to suffer first and most are individuals physically weak because of disability or age, those who suffer a culturally defined status that makes them vulnerable (such as an ethnic group or stigmatized class), and those who are already suffering a temporary personal or household economic crisis. On the other hand, a catastrophic shock may temporarily expose relatively well-off individuals and families to extreme hardship, inducing the need for immediate relief in the form of medical, nutritional or financial assistance.

It is important to emphasize again that target beneficiaries may be other than the poor or those in need of emergency relief. Projects that focus on production may deliberately exclude those who the most vulnerable—such as the landless or the physically or mentally incapacitated, i.e. people incapable or unlikely to assist in augmenting production. Projects with the goal of increasing regional production may focus on the relatively wealthy landowners. Other relatively wealthy beneficiary targets might be businesses and banks, or scholarships to individuals living in impoverished regions but who may not be impoverished themselves. Thus, we can add a fifth category to beneficiary criteria:

- Individuals, households, or institutions with capacity to increase production, thereby elevating local living standards through increased employment, availability of goods and services, or preservation of natural resources

Community Buy-in and Validity

An important dimension of criteria is whose criteria is it? Is the donor or implementing organization selecting the criteria? Or is the community somehow determining the criteria? Whose criteria is being used, how well it fits with community reality and values and whether or not the community members accept the criteria as justifiable have a great deal to do with winning community buy-in and avoiding conflict and resentment regarding the intervention. But buy-in must be balanced with validity of the criteria. There are many instances where community members do not share the objectives of the donors; where community consensus is that those who most deserve aid are not the neediest but the hardest workers, the entrepreneurially inclined, or even traditional elites. In cases such as these the values and goals of aid entities must somehow be reconciled with those of the community or, at the very least, community members must be convinced of the value of the intervention (see Himmelstine 2012).

Proxy Means Testing (searching for and validating criteria)

In all the guides and studies of Targeting reviewed, Proxy Means Testing (PMT) is considered a Beneficiary Selection technique. Specifically, PMT is the use of survey research and statistical methods to identify a multidimensional set of parameters by which qualifying households or individuals can be selected as aid recipients. For this reason it is better classified not with ‘beneficiary detection techniques’—as typically done– but rather as a tool for searching and/or validating criteria.

Beneficiary Selection Overview

Beneficiary Selection refers to how a program identifies individuals or organizations that meet their beneficiary criteria. In the literature, most studies present Beneficiary Selection as a single phase with the possible categories of Self-Selection (individuals come for aid on their own volition), Means Targeting (use of official lists of income such as tax or payrolls), Proxy-Means Testing (use of multivariate formulas the validity of which is substantiated—‘tested’—through representative survey sampling), and Community Based Targeting (the formation of community committees that make up lists of qualifying individuals). WFP (2006a) adds Administrative Targeting to the list by which they mean the use of formal organizations apparatus for targeting. This model aims to clarify ambiguities and differences in the models by lumping these all under the category of Beneficiary Selection and compartmentalizing them into a two stage process: ‘Selection of who will choose the beneficiaries’ and ‘selection of how the beneficiaries will be chosen.’ Each phase has a limited number of options.

Phase 1: selecting who will choose the beneficiaries

- Community Based Targeting is the managed use of community organization or individuals to determine if an individual meets beneficiary criteria. The process usually involves formation of a community committee assembled by the organization seeking to distribute aid. Typically, a balanced members are selected from governmental sectors, religious sectors, business sector, and credible community based organizations, usually including at least one organization comprised predominately of women, such as a mothers club. A list of common complications include elite capture, politics, community rivalries, and application of criteria (see Himmelstine 2012 for a review).

- Extension Targeting (ET): The use of health agents, social workers, or other auxiliaries working for NGO, government, or international organizations, and community based organization— existing association, schools, hospitals, churches or local governmental agencies whose staff are already working with the community in some capacity– to select beneficiaries who meet criteria. When the option is available, extension Targeting should be used for cost savings and effectiveness (can and should be combined with Admin-Targeting if possible; and preferred if organizations with selection capacity are present). A distinction can be made within Extension Targeting between formal institutions created for a purpose other than channeling aid—such as the schools, hospitals, churches and government agencies seen above—and organized local action groups (CBO)

- Survey Targeting: refers to a trained team that gathers quantitative or qualitative data on individuals, households, or some other group to determine who qualifies as a beneficiary. Qualitative survey targeting includes focus groups or community-participatory qualitative poverty ranking systems. An example of quantitative Survey Targeting is the traditional household survey or census. One expected advantage of quantitative over qualitative surveys is objective information. An advantage to the qualitative wealth-ranking or other strategies that draw on community participation is that they tap local knowledge and provide data that can discriminate inter-household vulnerability to degrees that we can never hope to achieve with quantitative surveys. These type of qualitative surveys also achieve high levels of community buy-in because criteria and ranking is determined in consultation with the community. Drawbacks of both Survey Targeting approaches are high costs.

Bottom-up vs. Top-Down Selection

A significant conditioning factor in the process being described is how those who choose beneficiaries are themselves chosen. In the case of CBT, even if we can be assured that the organizations and their representatives are credible, the approach can still be conceptualized as top down, and hence imposed on beneficiaries rather than participatory. To clarify, community leadership—as opposed to the beneficiaries themselves–is a point of departure; an unavoidable byproduct of the process is that Targeting is ultimately accomplished from their perspective or, when attempting to identify the most vulnerable, from outside the social peer strata of beneficiaries. Interesting in this regard is that during the course of the research for this report a common recommendation from beneficiaries was that someone poor be included in the selection committees.

The same is true of networks of professional extension workers—Extension Targeting–or trained volunteers and even surveyors. The selection of those who select beneficiaries is made outside the beneficiary social group and ultimately not subject to their scrutiny or control. Generalizing from the concept of World Bank consultants Mansuri and Rao (2013), it can be called an “induced” Targeting process.

On the other hand, when local CBOs are tasked with beneficiary selection we can speak of “organic” targeting. Even in the event an organization is created for the express purpose of capturing aid, the members often include intended beneficiaries. When tasked with identifying other beneficiaries they tend to select within their own social networks, which once again means that we are at least closer to the intended vulnerable populations than is the case when local elites control the process.

Both top-down and bottom-up approaches have their strengths and weaknesses. When selection of the selectors is made by people outside the community it allows for objectivity and the avoidance of three enemies of effective targeting: influence, bias, and favoritism. On the other hand, the decision is often made with little to no background knowledge, and little knowledge of the credibility of the people being entrusted. In the case of ‘organic’ selectors, members are definitively from the community—versus the leadership–but there is the tendency for some to be actively engaged in participating with the objective, not of including others, but helping themselves and their families and friends. There is a tendency to use of the task of beneficiary selection as means of reinforcing the institutional integrity of the local organization tasked with targeting and to build their own institution’s social capital. Indeed, when the selectors are embedded at lower levels of the community, even if they want to choose legitimately vulnerable beneficiaries, censure from family friends and neighbors means that they do it at their own peril, i.e. if one does not identify his or her spouse, brother, uncle, cousin or friend as a beneficiary the person will be shunned, or worse, for the oversight.

A mixture of bottom-up and top-down selection can be seen in community poverty mapping and wealth ranking schemes. These community mapping and wealth ranking schemes offer the advantage of tapping local knowledge but under the guidance, control, and with the objectivity of outsider participation. The problem here is, once again, high costs.

Phase 2: selecting what mechanism is used to choose beneficiaries

The second stage of Beneficiary Selection is ‘selection of how the beneficiaries will be chosen.’ As with who will do the selecting, discussed above, each phase has a limited number of options. Specifically, Self-Selection, Admin-List Selection, Network Selection, and a new technique, Freq-Listing, Selection by way of Frequency Listing.

- Self-Selection- individuals come to the program based on their own need, such that cash-for-work programs where pay is set at a low level draws only those individuals willing to work for low pay; subsidies to low-status staples draws only those individuals or families sufficiently in need that they will purchase and consume the staples; subsidies to public education draws only those families willing to put their children in the public education system.

- Admin-List Selection (ALS)- usually called ‘Means Targeting,’ is here redefined because of the ambiguity in the term “means.” The term “mean” is intended to designate ‘average income,” and has the double significance of the “means” by which people live, something that could and often does include non-monetary strategies—such as consumption from hunting, gathering, scavenging, fishing, agriculture, or barter. Admin-List Selection refers to data from surveys, tax rolls, lists of land ownership, fish catches, hunting quotas or any other compendium or data base available from a formal institution that provides information on consumption, assets, or receivables. The list is used to determine if an individual, household, or institution meets beneficiary criteria. In other studies in the literature, Means Targeting is classified as distinct from Proxy Means Targeting. In this study both Proxy Means and Wealth Ranking has been reclassified from a selective tool to a method of refining Criteria. Thus, the results of Proxy Means Testing and Wealth Ranking are included here in the resources for Admin-Lists, i.e. multivariate discriminatory criteria, based on multiple dimensions of livelihood security, such as income, house type, number of children in the house, and assets; and which are collected and consolidated in ‘list’ (data base) by a formal institution, in this case a survey team.[vi]

- Network Selection–similar to what in statistical sampling is called snow-ball surveys, beneficiaries are detected through individual or professional networks. For example, if CBT is used as the means of selecting those who select beneficiaries, then the CBT committee may—and in most cases examined during the field work for this study does—use their own professional, political or personal networks to determine if an organization, household or individual qualifies for aid according to the determined beneficiary criteria.

- Freq-Listing Selection: In this study we offer a fourth strategy for beneficiary detection, a modification of a technique from Cultural Concensus Analysis (Borgatti 1992); specifically, the elicitation of lists from a sample of respondents, thus combining sampling with local knowledge (see Frequency Listing).

Beneficiary Selection Conditioning Factors

In choosing which of the preceding detection strategies will or should be used, the first decisions are made easy or complex based on,

- if self-selection is deemed an option

- whether the targeting criteria is categorical vs. multivariate discriminatory

- the capacity of State, grassroots, private and international institutions already working in the area

Practical self-selection should be considered an option in some cases, particularly when associated with building infrastructure with cash or food for work. However, in cases where the goal is to directly reach the most vulnerable, it often is not practical because of the incapacity of many vulnerable people to perform work.

Regarding categorical vs. multivariate discriminatory criteria: the group targeted often defines the complexity of the task. Programs that focus on pregnant women, malnourished children, HIV or even peanut growers are categorical and require little effort in determining whether one qualifies as a beneficiary. Based on a pregnancy or HIV test a woman either is or is not pregnant and is or is not HIV positive; based on health status a child either is or is not malnourished; a farmer has or has not planted peanuts or a specific area of land. In these cases the challenge is not beneficiary selection but integrity and capacity of the entity that will do the actual selecting, i.e. who will the lists (Phase 1: “Selecting who chooses the beneficiaries”): CBT or Administrative networking.

In areas where strong State institutions, strong traditional grassroots institutions and leadership, or effective networks of auxiliary social workers are present, the challenge of beneficiary detection is made even easier, or even made for the targeting entity, as when State, military or local tribal leaders enforce their authority over the process. On the other hand, in the case of countries where there are few strong organizations or corruption and fractured politics make reaching the vulnerable exceptionally difficult, where official tax records do not exist or formal employment scarce, there are the options seen in the preceding section, specifically, Network Selection carried out via Community Based Targeting or Admin-List selection via extension services associated with churches, health out-reach programs, NGOs, volunteer disaster relief agencies, or some type of survey; and finally the Frequency Listing Strategy.

WORKS CITED

ALNAP. 2012 Responding To Urban Disasters: Learning From Previous Relief And Recovery Operations November www.alnap.org/resources/lessons.

Himmelstine, Carmen Leon 2012 Community Based Targeting: A Review of CBT programming and literature

Hoskins, A. 2004. Targeting General Food Distributions: Desk Review of Lessons from Experience. Rome, WFP).

Krishna, Anirudh 2010 “One Illness Away: Why People Become Poor and How they Escape Poverty” Oxford University Press

Lavallee, Emmanuelle, Anne Olivier, Laure Pasquier-Doumer, and Anne-Sophie Robilliard 2010 Poverty Alleviation Policy Targeting: a review of experiences in developing countries.

Mansuri, Ghazala and Vijayendra Rao 2013 Localizing Development Does Participation Work? International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

Maxwell, Daniel, Helen Young, Susanne Jaspars, Jacqueline Frize 2009 Targeting in Complex Emergencies Program Guidance Notes. Feinstein International Center, Tufts University

McClure, Marian 1984 Catholic Priests And Peasant Politics In Haiti: The Role Of The Outsider In A Rural Community A paper prepared for presentation at the Caribbean Studies Association meetings St. Kitts May 30 – June 3

PNUD 2000 Bilan commun de pays du PAM, du FNUAP, de l’UNICEF, de l’OMS/OPS et de la FAO. RPP

Scott, Lucy and Andrew Shepherd 2013 Microeconomic Indicators of Development Impacts and Available Datasets in Each Potential Case Study Country

Sharp, K. 1997. Targeting Food Aid in Ethiopia. London, Save the Children Fund. (Cited in WFP 2006b: 5).

Smillie, Ian 2001 Patronage or Partnership: Local Capacity Building in Humanitarian Crises Published in the United States of America by Kumarian Press, Inc. 1294 Blue Hills Avenue, Bloomfield, CT 06002 USA.

Steeve Coupeau 2008: 104 History of Haiti. Greenwood Press: Westport Ct.)

UN 1996 Final report on human rights and extreme poverty, submitted by the Special Rapporteur, Mr. Leandro Despouy’ (28 June 1996) UN Doc E/CN.4/Sub.2/1996/13

USAID 2013 Performance Indicators Reference Sheets for FFP Indicators http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/PIRS%20for%20FFP%20Indicators.pdf

WFP (undated_b) Monitoring & Evaluation Guidelines United Nations World Food Programme Office of Evaluation and Monitoring Via Cesare Giulio Viola, 68/70 – 00148 Rome, Italy Web Site: www.wfp.org

WFP 2006a TARGETING IN EMERGENCIES WFP/EB.1/2006/5‐A

WFP 2006b Thematic Review of Targeting in Relief Operations: Summary Report. Ref. OEDE/2006/1

WFP 2009 Targeting in Complex Emergencies, Programme Guidance. Feinstein International Center, Tufts Universtiy

WFP 2013 Basic Guidance Community-Based Targeting

WFP/EB.A/2004/5‐C).

WHO 2013. World Health Statistics http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2013/en/

Wiens, Thomas and Carlos Sobrado 1998 Rural Poverty in Haiti In Haiti: The Challenges of Poverty Reduction, World Bank Volume Il: Technical Papers Report No. 17242-HA

Wiesmann, Doris, Lucy Bassett, Todd Benson, and John Hoddinott 2009 Validation of the World Food Programme’s Food Consumption Score and Alternative Indicators of Household Food Security. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00870

World Bank 2013 Design & Implementation: Targeting and Selection. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection

NOTES

[i] http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment/brief/cdd-targeting-selection

[ii] Implied in this is just distribution of aid as, “[a]ssistance will be guided solely by need and will not discriminate in terms of ethnic origin, nationality, political opinion, gender, race or religion. In a country, assistance will be targeted to those most at risk from the consequences of food shortages, following a sound assessment that considers the different needs and” Humanitarian Principles (WFP/EB.A/2004/5‐C):

[iii] “… ensuring that food goes to people who need it and only those who need is critical to minimizing the collateral harm done by aid” (WFP: Targeting in Complex Emergencies, Programme Guidance Notes p 2)

[iv] Whether aid programs have achieved, the objectives of relieving suffering and promoting sovereignty are topics of contention. Whether or not harm has been done is vague and even in those cases where harm clearly has been one, it is seldom clear whether the good outweighs the bad: does saving 1,000 starving children while crashing the local agricultural market for 50,000 farmers justify the intervention?

[v] We do not include vulnerability analyses, needs assessments or mapping as we consider it a separate exercise, embedded in Beneficiary Detection Strategy.

[vi] Lavallee et al (2010) confine the definition to income but the same method can be used to profile families for criteria other than income, for example, land ownership, family size, refugee status, and victims of disaster: if they are on a list they qualify.

are examined in depth later in this report. However, what should also be included in this category are those entities or organizations used to pass aid on to recipients, what can be defined as “Intermediary Beneficiary Units.” These may be an enterprise, such as a bank, small business, school, or cooperative serving the poor; it may be a CBO, such as a church, orphanage, farming cooperative, or women’s association. Even NGOs, whether international or local, may themselves be conceptualized as Intermediary Beneficiary Units. The selection of a beneficiary unit at a level above the individual or household typically makes aid disbursement administratively easier for the organization because they can use the intermediaries system of beneficiary identification and distribution. But it often makes it more difficult to reach intended recipients because of the necessity of conforming to administrative and infrastructural exigencies. For example, financial assistance to CBOs (Community Based Organizations) is often contingent on their having a bank account, eliminating organizations with the most impoverished members or making them vulnerable to unscrupulous individuals who offer to facilitate access to banking services but intend to embezzle the aid; voucher programs may be conditional on the individual’s physical presence, eliminating the disabled or those individuals, often the poorest, who live in remote areas; assistance to school feeding programs may be conditional on secure dry storage facilities and proper accounting procedures, eliminating the most impoverished schools; assistance to children can be conditional on their being in school, eliminating the poorest children.

are examined in depth later in this report. However, what should also be included in this category are those entities or organizations used to pass aid on to recipients, what can be defined as “Intermediary Beneficiary Units.” These may be an enterprise, such as a bank, small business, school, or cooperative serving the poor; it may be a CBO, such as a church, orphanage, farming cooperative, or women’s association. Even NGOs, whether international or local, may themselves be conceptualized as Intermediary Beneficiary Units. The selection of a beneficiary unit at a level above the individual or household typically makes aid disbursement administratively easier for the organization because they can use the intermediaries system of beneficiary identification and distribution. But it often makes it more difficult to reach intended recipients because of the necessity of conforming to administrative and infrastructural exigencies. For example, financial assistance to CBOs (Community Based Organizations) is often contingent on their having a bank account, eliminating organizations with the most impoverished members or making them vulnerable to unscrupulous individuals who offer to facilitate access to banking services but intend to embezzle the aid; voucher programs may be conditional on the individual’s physical presence, eliminating the disabled or those individuals, often the poorest, who live in remote areas; assistance to school feeding programs may be conditional on secure dry storage facilities and proper accounting procedures, eliminating the most impoverished schools; assistance to children can be conditional on their being in school, eliminating the poorest children.